Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith

This is one of Donev’s most recognized frameworks. It emphasizes three core elements of Pentecostal spirituality:

- Prayer: Seen as the starting point of spiritual communication and personal experience with God.

- Power: The manifestation of divine presence through spiritual gifts and supernatural experiences.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community, reflecting both personal and collective identity.

This triangle encapsulates the holistic nature of Pentecostalism, where theology is deeply rooted in experience rather than abstract doctrine.

Restorationist Theology

Donev builds on the idea of primitivism—a return to the faith and practices of the early church. He critiques Wesleyan frameworks like the quadrilateral (Scripture, tradition, reason, experience) as insufficient for Pentecostal identity, arguing that Pentecostalism goes beyond Wesley to reclaim the apostolic era.

Historical-Theological Contributions

In his book The Unforgotten, Donev explores the theological roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria, tracing its development through key figures like Ivan Voronaev and the influence of Azusa Street missionaries. His research highlights:

- Trinitarian theology among early Bulgarian Pentecostals, shaped by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology and Western Pentecostal doctrine.

- Free will theology, emphasizing Armenian views over Calvinist predestination, due to Bulgaria’s Orthodox heritage and missionary influences.

Other Notable Works

- The Life and Ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev: A historical-theological study of one of the pioneers of Slavic Pentecostalism.

- Doctrine of the Trinity among Early Bulgarian Pentecostals: Explores how the Trinity was experienced and understood in early Eastern European Pentecostal context

The Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Introduction

Pentecostal theology has long emphasized the experiential dimension of faith—where divine encounter, spiritual gifts, and communal expression converge. Among the contemporary voices shaping this discourse, Dony K. Donev offers a compelling framework known as the Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith, which seeks to restore the apostolic essence of early Christianity. This essay explores the theological contours of Donev’s model and compares it with other influential Pentecostal and charismatic paradigms.

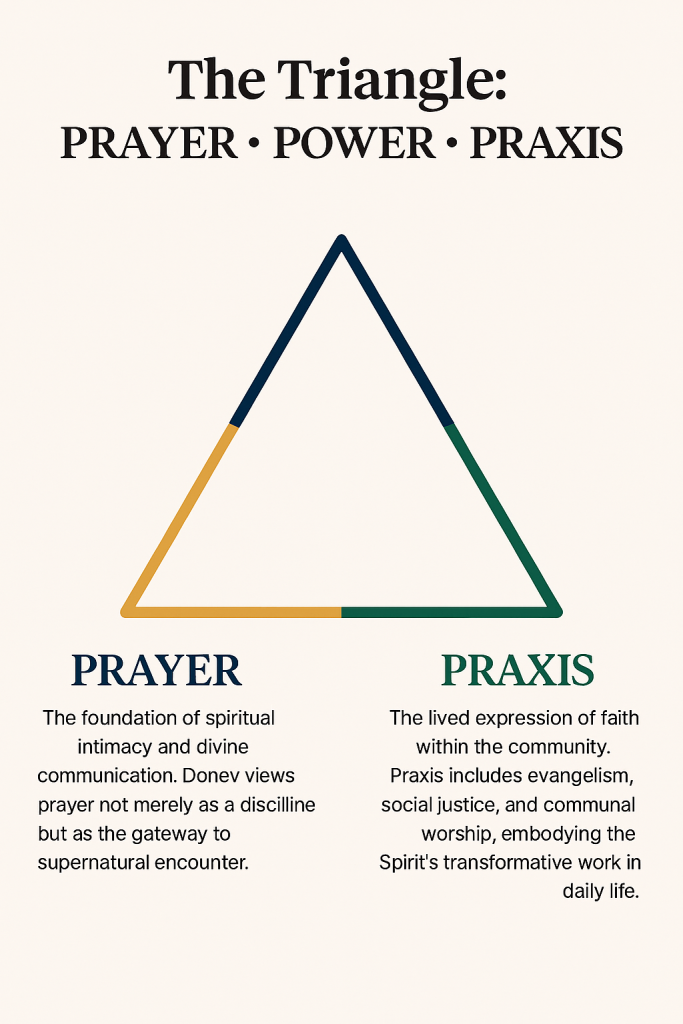

The Triangle: Prayer, Power, Praxis

At the heart of Donev’s framework lies a triadic structure:

- Prayer: The foundation of spiritual intimacy and divine communication. Donev views prayer not merely as a discipline but as the gateway to supernatural encounter.

- Power: Manifested through the gifts of the Spirit—healing, prophecy, tongues, and miracles. This element reflects the Pentecostal emphasis on dunamis, the Greek term for divine power.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community. Praxis includes evangelism, social justice, and communal worship, embodying the Spirit’s transformative work in daily life.

This triangle is not hierarchical but interdependent. Prayer leads to power, power fuels praxis, and praxis deepens prayer. Donev’s model thus reflects a restorationist impulse, aiming to recover the vibrancy of the early church as seen in Acts.

Comparison with Wesleyan Quadrilateral

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral—Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience—has historically shaped Methodist and Holiness theology. Pentecostals have often adopted this model, emphasizing experience as a key source of theological reflection.

However, Donev critiques this framework as insufficient for Pentecostal identity. He argues that Pentecostalism is not merely an extension of Wesleyanism but a distinct restoration movement. While Wesley’s model is epistemological, Donev’s triangle is ontological and missional, rooted in being and doing rather than knowing.

Comparison with Classical Pentecostal Theology

Classical Pentecostalism, as shaped by early 20th-century leaders like Charles Parham and William Seymour, emphasized:

- Initial evidence doctrine: Speaking in tongues as proof of Spirit baptism.

- Dispensational eschatology: A belief in imminent rapture and end-times urgency.

- Holiness ethics: A call to moral purity and separation from the world.

Donev’s framework diverges by focusing less on doctrinal distinctives and more on spiritual vitality and historical continuity. His emphasis on praxis aligns with newer Pentecostal movements that prioritize social engagement and global mission.

Comparison with Charismatic Theology

Charismatic theology, especially within mainline and evangelical churches, often emphasizes:

- Renewal within existing traditions

- Broad acceptance of spiritual gifts

- Less emphasis on tongues as initial evidence

Donev’s triangle shares the Charismatic focus on spiritual gifts but retains a Pentecostal distinctiveness through its restorationist lens. He seeks not just renewal but recovery of primitive faith, making his model more radical in its ecclesiological implications.

Eastern European Context and Trinitarian Theology

Donev’s work is also shaped by his Bulgarian heritage. He highlights how early Bulgarian Pentecostals embraced a Trinitarian theology informed by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology. This contrasts with Western Pentecostalism’s often fragmented view of the Spirit.

His emphasis on free will theology—influenced by Arminianism and Orthodox thought—also sets his framework apart from Calvinist-leaning Charismatic circles.

Conclusion

Dony K. Donev’s Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith offers a rich, experiential, and historically grounded model for understanding Pentecostal spirituality. By centering prayer, power, and praxis, Donev reclaims the apostolic fervor of the early church while challenging existing theological paradigms. His framework stands as a bridge between classical Pentecostalism, Charismatic renewal, and Eastern Christian traditions—inviting believers into a deeper, more dynamic walk with the Spirit.

Comparative Insights from Leading Pentecostal Scholars

Gordon Fee: Scripture-Centered Pneumatology

Fee’s scholarship emphasizes the Spirit’s role in New Testament theology, particularly in Pauline writings. While he critiques traditional Pentecostal doctrines like initial evidence, he affirms the Spirit’s transformative presence. Compared to Donev, Fee’s approach is exegetical and text-driven, whereas Donev’s triangle is experiential and restorationist, prioritizing lived encounter over doctrinal precision.

Stanley M. Horton: Doctrinal Clarity and Holiness

Horton’s work, especially in Bible Doctrines, provides a systematic articulation of Pentecostal beliefs, including Spirit baptism and sanctification. His theology is deeply rooted in Assemblies of God tradition. Donev diverges by de-emphasizing denominational boundaries, focusing instead on the primitive church’s egalitarian and Spirit-led ethos.

Craig Keener: Charismatic Experience and Historical Context

Keener bridges academic rigor with charismatic openness, especially in his work on miracles and Acts. His emphasis on historical plausibility and global charismatic phenomena aligns with Donev’s praxis-driven model. However, Keener’s scholarship is more apologetic and evidential, while Donev’s triangle is formational and communal.

Frank Macchia: Spirit Baptism and Trinitarian Theology

Macchia’s theology centers on Spirit baptism as a metaphor for inclusion and transformation, often framed within Trinitarian and sacramental lenses. Donev shares Macchia’s Trinitarian depth, especially in Eastern European contexts, but leans more toward neo-primitivism and ecclesial simplicity.

Vinson Synan: Historical Continuity and Global Pentecostalism

Synan’s historical work traces Pentecostalism’s roots and global expansion. Donev builds on this by reclaiming Eastern European Pentecostal narratives, such as those of Ivan Voronaev. Both emphasize restoration, but Donev’s triangle is more prescriptive, offering a model for future church practice.

Robert Menzies: Missional and Contextual Theology

Menzies focuses on Pentecostal mission and theology in Asian contexts, often challenging Western assumptions. His emphasis on Spirit empowerment for mission resonates with Donev’s praxis element. Yet, Donev’s model is more liturgical and communal, drawing from Orthodox and Puritan influences.

Cecil M. “Mel” Robeck: Ecumenism and Pentecostal Identity

Robeck’s work on Pentecostal ecumenism and global dialogue complements Donev’s inclusive vision. Both advocate for Pentecostal distinctiveness without isolation, though Donev’s triangle is more grassroots and revivalist, aimed at local church transformation.

Implications for Church Practice

Donev’s triangle offers a practical blueprint for churches seeking renewal:

- Prayer ministries that foster intimacy and prophetic intercession.

- Power encounters through healing services and spiritual gift activation.

- Praxis initiatives like community outreach, justice advocacy, and discipleship.

Compared to other scholars, Donev’s model is less academic and more actionable, designed to reignite the apostolic fire in everyday church life.

Christmas: A story about a Middle Eastern family seeking refuge

Bulgaria still set to adopt the Euro despite massive protests

Bulgaria is still set to adopt the Euro on January 1, 2026, despite massive anti-government and anti-corruption protests that recently led to the Prime Minister’s resignation, though the political turmoil has created uncertainty and concerns about fair elections and potential delays, with some fearing inflation and Russian disinformation influencing the opposition. The country faces a government vacuum and upcoming early elections, but the Eurozone entry, a major EU step, remains legally on track, though public opinion is divided.

- Euro Adoption: Bulgaria is scheduled to become the 21st Eurozone member on January 1, 2026, replacing its currency, the lev.

- Protests & Politics: Recent widespread protests, initially against a controversial budget plan, evolved into demands for resignation and fair elections, leading to the center-right government’s collapse.

- Reasons for Protests: Concerns include corruption, influence of oligarchs (like Delyan Peevski), and alleged election manipulation, with accusations of Russian social media campaigns fueling anti-Euro sentiment.

- Public Opinion: About half of Bulgarians oppose the Euro, fearing price hikes, though the European Central Bank suggests inflation impact will be modest.

- Current Situation: The country lacks a government and budget for 2026, with a caretaker government expected to be appointed, but Euro entry is considered legally irreversible

Bulgaria holds consultations for new government

Bulgarian government resigns amid protests

Dr. Dony K. Donev: Introduction to John 5

-

Focus on a small part of Chapter 5; full chapter will be addressed in another talk.

-

Expository Bible study principle: do not omit what the author intends; understand the context.

-

John’s Gospel narrative in brief:

-

Chapter 1 – Creation and beginning.

-

Chapter 2 – Christ’s first miracle (water to wine).

-

Chapter 3 – Nicodemus and questions of faith.

-

Chapter 4 – Woman at the well.

-

Chapter 5 – Paralytic man (focus of this study).

-

Application: We see ourselves in these stories:

- At the well with the woman.

- With the paralytic, facing sickness or oppression.

- In creation, asking questions about beginnings.

- John’s Gospel speaks to our lives and experiences.

Verse 1: Context & Significance

-

“The Feast of the Jews” = Passover (second recorded Passover Jesus attended).

-

Chronology: Jesus ministered ~3–3.5 years, not four.

-

Johannian phrase: “After these things…” (Greek: meta tauta). Contextually links back to previous events (Samaritan woman, previous miracles).

Verse 2: Present Continuous Action

-

“Now was” vs. “there was” → emphasizes ongoing reality.

-

Location: Sheep Gate, Pool of Bethesda (“House of Mercy”), five porches.

-

Historical significance: gate restored by Nehemiah; miracles happen through preparation and prior work.

-

Water symbolism: continuous in John’s Gospel.

Verse 3: The Multitude at Bethesda

-

People lying on porches: sick, blind, lame, paralyzed, waiting for the stirring of the water.

-

Place functioned like a hospital or hospice, offering mercy but not healing.

-

Importance: highlights the need for action, faith, and not just passive waiting.

Verse 4: Angel’s Stirring of Water

-

Angel stirred water; first to enter after stirring was healed.

-

Greek: “troubling” of water → divine or angelic activity.

-

Step of faith required to enter: miracle is available, but effort is needed.

Verse 5–7: The Paralytic Man

-

Man had been ill for 38 years.

-

His theology: “A man have I none…” → depended on others, not God directly.

-

Lesson: don’t wait on another; God can act directly.

-

Human tendency: self-pity, victim mentality.

-

Jesus asks: “Do you want to be well?” – Highlights awareness, desire for change, and personal responsibility.

Verse 8: Jesus Commands Healing

-

“Rise, take up thy bed and walk.”

-

Immediate healing, resurrection-like command (Greek: anistemi).

-

Significance: ignores self-pity, performs the miracle directly.

-

Steps in healing: man immediately rises, strength restored, carries his bed/stretcher.

-

Application: miracles require obedience and action; prior failures don’t prevent success.

Verse 10–12: Testing by Religious Leaders

-

Sabbath controversy: “It is not lawful to carry thy bed.”

-

Misplaced focus: rules over divine action.

-

Observation: miracle transcends human rules; legalistic thinking may blind people to God’s power.

-

The healed man didn’t initially know who Jesus was → possible to receive miracle without knowing fully, but sustaining it requires knowing God.

Verse 14: Warning Against Sin

-

Jesus instructs: “Sin no more, lest a worse thing come unto thee.”

-

Connection: healing is not just physical but spiritual; continued obedience sustains the miracle.

Key Observations & Theological Lessons

-

The man who had no human helper was found by the Son of Man who created all men.

-

Healing is a believer’s right; Jesus administers it within the covenant of creation, restoring balance to the universe.

-

Miracles point to Christ as the central figure (water symbolism, “man of the hour”).

-

Faith, obedience, and direct encounter with God are crucial.

Practical Applications

-

Everyone can receive a miracle.

-

God makes healing and restoration possible.

-

Personal faith and obedience maintain the miracle in daily life.

-

Step of faith is often required; God provides directly.

365 Daily Thought Stirring Stories from the Field

In 1999, Dony and Kathryn established Cup & Cross Ministries International with a vision for restoration of New Testament theology and praxis. Today they have over 50 years of combined commitment to Kingdom work. This book invites you to spend a few moments each day on the field sharing their experiences of serving as pastors, evangelists, chaplains, consultants, church trainers, researchers, missionaries and educators of His Harvest around the globe.

Pile of Dusty Bones

It is not good for man to be alone. God recognized that the animals he had already created could not be a companion for Adam so He made woman, a unique design to complete man. Genesis 2:23 Adam realizes this truth as “bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh.” They become one flesh. They together are completeness and togetherness. Adam is man plus Eve only. Not Adman and man. Woman means taken out of man and gives glory to man. Together male and female have child bearing capabilities to multiply the earth. Gen 1:22 reveals God’s plan for preproduction which can only happen between a male and a female. Any other way of reproducing is not part of God’s plan. Man and man cannot make man.

Mark 10:6 shows that the purpose of male and female is the creation of the family for preservation. Yet when family is no longer an integrated unit this is a sign of moral and spiritual breakdown of a nation. What God has joined let no man put asunder. Marriage is of God. It is sacred a union. When we attempt to go against God’s plan, we just get a pile of dry dusty bones.

BLACK FRIDAY BOOK SALE

All books by Cup&Cross on SALE

Final clearance sale for the year with new titles coming up in early 2021

CLICK the picture below to view all titles on Amazon.com

Dr. Dony K. Donev: Eschatology in the Gospel of John

Eschatology in the Gospel of John (2024 EPIC REVIVAL)

There is no synoptic agreement regarding eschatology in the Gospel of John. Unlike Matthew, Mark, and Luke, there is no single chapter in John that deals exclusively with the end times. Yet, eschatology is present in every chapter of John’s Gospel.

John, in contrast to the synoptic writers, sets forth a realized eschatology, where Jesus’ message proclaims the eternal breaking into the temporal world.

The Nature of Johannine Eschatology

In the Fourth Gospel, Jesus uses apocalyptic language to describe the transcendental nature of the Kingdom of God. John presents the Early Church with a dual futuristic reality:

-

To be saved with God toward eternal life in this lifetime, and

-

Then to enter eternal life in eternity itself.

These are not the same, according to John’s Epistles, where the apostle uses the present continuous tense to indicate that salvation must persist through life into eternity.

Thus, the terminology of the Fourth Gospel projects both the present and the future within Jesus Christ.

The Names of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel

The Gospel of John names Jesus in ways that reveal His eschatological role:

-

“Savior of the world” – offering salvation through His sacrifice.

-

“Son of Man” – pointing to His earthly ministry leading to the Cross.

-

“Son of God” – revealing His eternal existence and post-resurrection glorification.

-

“Messiah” – pointing to His future coming Kingdom.

These titles demonstrate existentialization in Johannine eschatology, where the resurrection, parousia, and the coming of the Holy Spirit are not separate events but one unified promise.

The “Already” and “Not Yet” of Eternal Life

In John 5:28–29, we encounter an example of primitive Christian eschatology. John presents both a “not yet” (future) and an “already” (present) dimension of eternal life. This creates a tension between the already fulfilled and the not yet completed.

In John 6:40, 53–54, Jesus links eternal life (spiritual) with resurrection life (physical).

The Six Eschatological Themes in John

Eschatological themes in John are not concentrated in one section, but spread throughout the Gospel. The six major areas are:

-

Death

-

Heaven

-

Judgment

-

Resurrection

-

Eternal Life

-

Christ’s Return

These themes appear in 16 of the 21 chapters, especially in chapters 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, and 12.

References found in John:

-

34 references to death

-

26 to heaven

-

21 to judgment

-

18 to eternal life

-

4 to Christ’s return

Death and Dying

In John, death and dying have both present and future, physical and spiritual aspects.

Spiritual death is the present condition of those who reject the word of the Son.

Physical and spiritual death must not be confused, just as physical and spiritual (eternal) life must remain distinct.

In John 6:58, eating the bread from heaven—that is, receiving Jesus Christ—keeps one from spiritual death and provides eternal life.

Eternal Life

The one who receives eternal life is delivered from judgment (3:17–19; 5:24).

Jesus assures that such a person will never perish, and that no one can remove them from His care (10:28).

In John 5:24, Jesus connects eternal life to hearing His word. The Greek term akouō means not merely to hear, but to hear and to do His word.

Jesus explains that the Father “has life in Himself” (5:26), being uncaused and independent. Since the Son shares the same divine essence, He partakes in this same eternal quality.

Again, John’s eschatology holds both a present and future dimension of eternal life—the “already” and the “not yet.”

Resurrection

In John 5:19–29, we find three of Jesus’ “truly, truly” (Amen, Amen) statements. In verses 19–23 and 25–29, resurrection truths are revealed.

Jesus claims power and authority over resurrection and life, equal to that of the Father (5:21).

The Son of Man is directly associated with resurrection in verses 28–29.

During His earthly ministry, only some of the dead heard His voice (such as Lazarus and Jairus’ daughter). But in the eschaton, “all” the dead will hear His voice and rise from the tombs.

Thus, the God who calls forth resurrection becomes our eschatological hope for the future.

Heaven

In John’s Gospel, “heaven” is referenced both directly and through terms like “above,” “my Father’s house,” or “a place for you.”

These passages affirm that heaven is a real place with definite location and purpose, providing future hope for believers.

Jesus teaches that the realities of heaven stand in contrast to those of earth (3:12).

All genuine blessings come from heaven—that is, from God (3:27).

The bread from heaven (6:31–33) provides eternal life and is equated with Jesus Himself (6:38).

In chapters 14 and 16, Jesus describes heaven as going to the Father, and calls it “my Father’s house” and “a place for you” (14:2–3).

The only other use of “my Father’s house” (2:16) refers to the temple, linking earthly worship to heavenly fulfillment—just as Revelation describes heaven without a temple, for the Lamb is its temple.

Judgment

John’s Gospel presents judgment as both present and future.

Those already judged by God now will also face judgment in eternity—unless they are born again.

Jesus uses two key terms for judgment:

-

krinō – to judge, separate, or condemn.

-

apollymi – to perish, the opposite of being saved.

John’s presentation of judgment falls into three categories:

-

The Judge – Christ Himself.

-

The Judged – humanity.

-

The Standard of Judgment – God’s truth and word.

Christ’s Return

The Gospel references Jesus’ coming in several senses.

John 14:2–3 and 21:22–23 refer to the Parousia, His second coming.

John 14:28 and 16:16–22 may refer to His return to the disciples through His resurrection.

Revelation later expands this concept, depicting Christ returning with His saints.

Eschatology in Revelation 1

The six eschatological themes from John reappear in Revelation 1:

-

Death and dying – “I was dead.”

-

Eternal life – “I am Alpha and Omega, the first and the last.”

-

Judgment – “Every eye shall see Him, and they also which pierced Him.”

-

Resurrection – “I was dead but live forevermore.”

-

Return – “Behold, He cometh with clouds; and every eye shall see Him.”

Revelation reveals the invisible God made visible—the God of Light who created light so that He might be seen by all in the last day.

We see the Light in John, and the Light glorified in Revelation.

The rejected God of John now returns victorious in Revelation.

The Speaking God

Beside the Light, we have the Word spoken by the Voice:

“Then I turned to see the voice that spoke with me” (Revelation 1:12).

The God who spoke in Genesis still speaks today.

You are not alone, nor without direction—turn from your understanding to the Voice who speaks through the ages.

The Call to Respond

God was moving in a new way in Revelation, and John wanted to be part of it.

He was told that revelation would unfold in three stages:

-

The things that you hear

-

The things that you see

-

The things that you experience

Reflect personally:

-

What do you hear in your life—just the noise of the world?

-

What do you see—failure, depression, or God?

-

What do you experience—an empty church or the living Christ?

Turning to See the Voice

John said, “I turned to see the voice” (Rev. 1:12).

It is time to move beyond merely hearing His voice and begin to see Him face to face.

When God speaks, three things happen:

-

He has a plan.

-

He has the power to do it.

-

No one can stop Him.

Seeing the Voice of God

How can we see the voice of God?

Just as creation saw it when He said, “Let there be light.”

But today, we have become too dignified, too busy, too proud to follow His way.

We must turn from our own ways to see Jesus:

a. Turn from your way to see The Way.

b. Turn from your truth to see The Truth.

c. Turn from your life to see The Life.

In the Hand of God

How do we turn? By trusting the hand of God.

“He laid His right hand upon me” (Rev. 1:17).

In verse 16, Jesus holds seven stars, representing the angels of the seven churches—not only the good churches, but all seven.

The seven stars remind us that God has not left us; we are still in His hand.

It is the same hand that was nailed on Calvary,

the same hand that created the world,

and the same hand that holds the future of all creation.

Are you in the hand of God today?

Does your family need that touch?

The Ultimate Question

All these studies mean nothing if we do not make it to heaven.

If we do not meet again in this life,

may we meet in heaven.