Collapse of the Western Theological Corpus: Conquistadorial Colonial Theology Toward the Global South is Over

Bridges to people and culture do not work any longer because they never touch the water of troubled cross-cultural issues. For the same reason, contextual theology does not work any more – once faced with the deep cross-cultural crises of faith and conviction, it sinks with no hope.

We have long observed the collapse of the “Western Theological Corpus,” as Andrew Walls calls the structural problem in missions today. Main reason for its collapse is the failure to give answers to the theological questions emerging from the Global South. As a result, the colonial approach of doing missions, resonating in imperialistic cross-cultural ministry and ethnic conquest for assimilation of cultures, all have failed both the indigenous people and the mission sending agencies. Prayer has hence turned into a protest and prophecy for a new reality, where the encounter of missions is no less than the very cross-roads where we encounter God and others together.

Doing Missions in the Spirit in 2018

365 Daily Thought Stirring Stories from the Field

In 1999, Dony and Kathryn established Cup & Cross Ministries International with a vision for restoration of New Testament theology and praxis. Today they have over 50 years of combined commitment to Kingdom work. This book invites you to spend a few moments each day on the field sharing their experiences of serving as pastors, evangelists, chaplains, consultants, church trainers, researchers, missionaries and educators of His Harvest around the globe.

Dr. Dony K. Donev: Eschatology in the Gospel of John

Eschatology in the Gospel of John (2024 EPIC REVIVAL)

There is no synoptic agreement regarding eschatology in the Gospel of John. Unlike Matthew, Mark, and Luke, there is no single chapter in John that deals exclusively with the end times. Yet, eschatology is present in every chapter of John’s Gospel.

John, in contrast to the synoptic writers, sets forth a realized eschatology, where Jesus’ message proclaims the eternal breaking into the temporal world.

The Nature of Johannine Eschatology

In the Fourth Gospel, Jesus uses apocalyptic language to describe the transcendental nature of the Kingdom of God. John presents the Early Church with a dual futuristic reality:

-

To be saved with God toward eternal life in this lifetime, and

-

Then to enter eternal life in eternity itself.

These are not the same, according to John’s Epistles, where the apostle uses the present continuous tense to indicate that salvation must persist through life into eternity.

Thus, the terminology of the Fourth Gospel projects both the present and the future within Jesus Christ.

The Names of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel

The Gospel of John names Jesus in ways that reveal His eschatological role:

-

“Savior of the world” – offering salvation through His sacrifice.

-

“Son of Man” – pointing to His earthly ministry leading to the Cross.

-

“Son of God” – revealing His eternal existence and post-resurrection glorification.

-

“Messiah” – pointing to His future coming Kingdom.

These titles demonstrate existentialization in Johannine eschatology, where the resurrection, parousia, and the coming of the Holy Spirit are not separate events but one unified promise.

The “Already” and “Not Yet” of Eternal Life

In John 5:28–29, we encounter an example of primitive Christian eschatology. John presents both a “not yet” (future) and an “already” (present) dimension of eternal life. This creates a tension between the already fulfilled and the not yet completed.

In John 6:40, 53–54, Jesus links eternal life (spiritual) with resurrection life (physical).

The Six Eschatological Themes in John

Eschatological themes in John are not concentrated in one section, but spread throughout the Gospel. The six major areas are:

-

Death

-

Heaven

-

Judgment

-

Resurrection

-

Eternal Life

-

Christ’s Return

These themes appear in 16 of the 21 chapters, especially in chapters 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, and 12.

References found in John:

-

34 references to death

-

26 to heaven

-

21 to judgment

-

18 to eternal life

-

4 to Christ’s return

Death and Dying

In John, death and dying have both present and future, physical and spiritual aspects.

Spiritual death is the present condition of those who reject the word of the Son.

Physical and spiritual death must not be confused, just as physical and spiritual (eternal) life must remain distinct.

In John 6:58, eating the bread from heaven—that is, receiving Jesus Christ—keeps one from spiritual death and provides eternal life.

Eternal Life

The one who receives eternal life is delivered from judgment (3:17–19; 5:24).

Jesus assures that such a person will never perish, and that no one can remove them from His care (10:28).

In John 5:24, Jesus connects eternal life to hearing His word. The Greek term akouō means not merely to hear, but to hear and to do His word.

Jesus explains that the Father “has life in Himself” (5:26), being uncaused and independent. Since the Son shares the same divine essence, He partakes in this same eternal quality.

Again, John’s eschatology holds both a present and future dimension of eternal life—the “already” and the “not yet.”

Resurrection

In John 5:19–29, we find three of Jesus’ “truly, truly” (Amen, Amen) statements. In verses 19–23 and 25–29, resurrection truths are revealed.

Jesus claims power and authority over resurrection and life, equal to that of the Father (5:21).

The Son of Man is directly associated with resurrection in verses 28–29.

During His earthly ministry, only some of the dead heard His voice (such as Lazarus and Jairus’ daughter). But in the eschaton, “all” the dead will hear His voice and rise from the tombs.

Thus, the God who calls forth resurrection becomes our eschatological hope for the future.

Heaven

In John’s Gospel, “heaven” is referenced both directly and through terms like “above,” “my Father’s house,” or “a place for you.”

These passages affirm that heaven is a real place with definite location and purpose, providing future hope for believers.

Jesus teaches that the realities of heaven stand in contrast to those of earth (3:12).

All genuine blessings come from heaven—that is, from God (3:27).

The bread from heaven (6:31–33) provides eternal life and is equated with Jesus Himself (6:38).

In chapters 14 and 16, Jesus describes heaven as going to the Father, and calls it “my Father’s house” and “a place for you” (14:2–3).

The only other use of “my Father’s house” (2:16) refers to the temple, linking earthly worship to heavenly fulfillment—just as Revelation describes heaven without a temple, for the Lamb is its temple.

Judgment

John’s Gospel presents judgment as both present and future.

Those already judged by God now will also face judgment in eternity—unless they are born again.

Jesus uses two key terms for judgment:

-

krinō – to judge, separate, or condemn.

-

apollymi – to perish, the opposite of being saved.

John’s presentation of judgment falls into three categories:

-

The Judge – Christ Himself.

-

The Judged – humanity.

-

The Standard of Judgment – God’s truth and word.

Christ’s Return

The Gospel references Jesus’ coming in several senses.

John 14:2–3 and 21:22–23 refer to the Parousia, His second coming.

John 14:28 and 16:16–22 may refer to His return to the disciples through His resurrection.

Revelation later expands this concept, depicting Christ returning with His saints.

Eschatology in Revelation 1

The six eschatological themes from John reappear in Revelation 1:

-

Death and dying – “I was dead.”

-

Eternal life – “I am Alpha and Omega, the first and the last.”

-

Judgment – “Every eye shall see Him, and they also which pierced Him.”

-

Resurrection – “I was dead but live forevermore.”

-

Return – “Behold, He cometh with clouds; and every eye shall see Him.”

Revelation reveals the invisible God made visible—the God of Light who created light so that He might be seen by all in the last day.

We see the Light in John, and the Light glorified in Revelation.

The rejected God of John now returns victorious in Revelation.

The Speaking God

Beside the Light, we have the Word spoken by the Voice:

“Then I turned to see the voice that spoke with me” (Revelation 1:12).

The God who spoke in Genesis still speaks today.

You are not alone, nor without direction—turn from your understanding to the Voice who speaks through the ages.

The Call to Respond

God was moving in a new way in Revelation, and John wanted to be part of it.

He was told that revelation would unfold in three stages:

-

The things that you hear

-

The things that you see

-

The things that you experience

Reflect personally:

-

What do you hear in your life—just the noise of the world?

-

What do you see—failure, depression, or God?

-

What do you experience—an empty church or the living Christ?

Turning to See the Voice

John said, “I turned to see the voice” (Rev. 1:12).

It is time to move beyond merely hearing His voice and begin to see Him face to face.

When God speaks, three things happen:

-

He has a plan.

-

He has the power to do it.

-

No one can stop Him.

Seeing the Voice of God

How can we see the voice of God?

Just as creation saw it when He said, “Let there be light.”

But today, we have become too dignified, too busy, too proud to follow His way.

We must turn from our own ways to see Jesus:

a. Turn from your way to see The Way.

b. Turn from your truth to see The Truth.

c. Turn from your life to see The Life.

In the Hand of God

How do we turn? By trusting the hand of God.

“He laid His right hand upon me” (Rev. 1:17).

In verse 16, Jesus holds seven stars, representing the angels of the seven churches—not only the good churches, but all seven.

The seven stars remind us that God has not left us; we are still in His hand.

It is the same hand that was nailed on Calvary,

the same hand that created the world,

and the same hand that holds the future of all creation.

Are you in the hand of God today?

Does your family need that touch?

The Ultimate Question

All these studies mean nothing if we do not make it to heaven.

If we do not meet again in this life,

may we meet in heaven.

COVID and the AMPA receptors of the brain

The conversation began by highlighting the ongoing impact of long COVID, specifically focusing on individuals who continue to experience symptoms like brain fog long after the pandemic’s initial phases. A recent study published in Brain Communications provided the first biological evidence explaining this phenomenon. Researchers discovered changes in AMPA receptors of the brain, which are crucial for memory and learning, potentially linking these changes to cognitive impairments commonly associated with long COVID. Utilizing cutting-edge PET imaging, the study compared brain scans of those with long COVID to those without, revealing increased AMPA receptor densities in affected individuals.

Dr. Deepak Nair pointed out that the study’s findings were intriguing, noting that those with brain fog showed an upregulation of AMPA receptors, linking this to possible cognitive function decline. However, the findings suggest that increased AMPA activity is only part of the picture; an overactive immune response in the brain, potentially triggered by COVID infections, might also contribute. Researchers identified inflammatory markers that coincided with increased AMPA receptor levels, indicating that these immune responses might underlie the receptor changes and associated cognitive issues.

Despite these promising insights, the study remains in its early stages. Dr. Nair highlighted the need for additional context, such as the COVID status of the control group, to further validate the results. While the study did not propose a specific treatment, it offers a direction for scientists to explore, such as developing medications targeting AMPA receptor activity to help alleviate brain fog symptoms. According to Dr. Takuya Takahashi, recognizing brain fog as a legitimate condition could inspire the healthcare industry to develop better diagnostic tools and treatments, offering hope to those still battling the long-term effects of COVID-19.

Primary Framework: The USHER Model of Communion

The U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion (or USHER Model)

-

Creator: Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

-

Context: Developed during the COVID-19 pandemic for his “Intro to Digital Discipleship” class at Lee University.

-

Core Purpose: To answer the question “What follows communion?” in Christian practice and catechism. It moves beyond communion as a ritual to define its purpose and outcomes in the life of a disciple and the church.

-

The Five Dynamics:

-

U – Unity: Communion fosters spiritual unity among believers, breaking down barriers and creating one body in Christ.

-

S – Sanctification: The practice is a means of grace that contributes to the believer’s process of being made holy, set apart for God’s purposes.

-

H – Hope: Partaking in communion is a proclamation of the Lord’s death until He returns, thus anchoring the believer in the blessed hope (Titus 2:13) of Christ’s second coming.

-

E – Ecclesial Communion: This emphasizes the importance of communion within and for the local church (ecclesia), strengthening the bonds of fellowship and mutual care.

-

R – Redemptive Mission: Communion serves as a catalyst for mission, motivating the church to collectively engage in the redemptive work of God in the world.

-

Other Associated Frameworks and Concepts

Dr. Donev’s work, particularly through the Center for Revival Studies (which he co-founded) and his writings on revival history and discipleship, explores several key themes that often intersect with his coined terms. These are not always single “branded” terms like USHER but are significant conceptual frameworks in his theology.

-

Digital Discipleship:

-

While not a term he solely coined, he has been a primary architect of its theological framework. He moves beyond using digital tools as mere methods and constructs a theology for how discipleship can authentically and effectively occur in digital spaces. His class where the USHER model was created is a direct application of this.

-

-

Theology of Revivalism:

-

Donev’s work heavily focuses on defining and analyzing revival, particularly from a historical (e.g., Balkan, Slavic, and Pentecostal) perspective. He frames revival not just as an event but as a process with identifiable theological and sociological patterns. His book “The Covenant of Peace: God’s Dream for the World” delves into this.

-

-

Covenant Community:

-

A recurring theme in his work is the concept of the church as a covenant community. This framework views the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants, which directly connects to the “Unity” and “Ecclesial Communion” aspects of the USHER model.

-

-

The “Why” of Discipleship:

-

Much of Donev’s writing and teaching focuses on moving beyond the “how” to the “why” of spiritual practices. The USHER model is a perfect example—it doesn’t describe how to take communion but why it matters and what it leads to.

-

Summary Table for Clarity

| Term/Framework | Description | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| USHER Model of Communion | Primary Coined Term. A 5-point framework (Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, Redemptive mission) defining the outcomes of communion. | Digital Discipleship, Catechism, Liturgy |

| Digital Discipleship | A theological framework for making disciples in online/digital environments, moving beyond mere methodology. | Modern Ministry, Post-COVID Church, Technology & Theology |

| Theology of Revivalism | A framework for understanding revival as a historical and theological process with identifiable patterns. | Church History, Pentecostal Studies, Spiritual Renewal |

| Covenant Community | A conceptual framework viewing the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants. | Ecclesiology (Doctrine of the Church), Community Formation |

In essence, while the USHER Model of Communion is his most clearly defined and coined term, Dr. Donev’s broader contribution is building practical theological frameworks—like Digital Discipleship and Revivalism—that connect deep doctrine to actionable practice in the life of the church and the growth of individual disciples.

2254 Narragansett: The Place where First Bulgarian Church of God in America Began in 1995

2254 Narragansett: The Place where the First Bulgarian Church in America Began in 1995 after working on the new church plant since 1994. With a sequence of startup events including a July 4th block party and Bulgarian picnic, first official services in Bulgarian language was held on July 10, 1995. With over a dozen Bulgarians present at 1 PM that memorable Sunday, Rev. Dony K. Donev delivered a the first message for the newly established congregation from Genesis ch. 18.

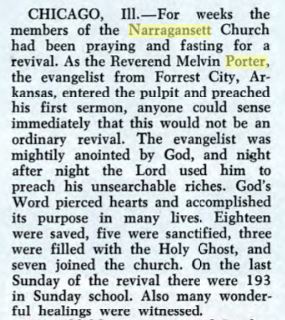

Narraganset holds a significant place in Church of God (Cleveland, TN) history. Narraganset Church of God was started by a women-preacher with only 10 members. Rev. Amelia Shumaker started the church only 15 days before the Great Depression began in 1929. https://cupandcross.com/90-years-ago

Rev. James Slay of the Narragansett Church of God in Chicago was commissioned to write the 1948 Church of God Declaration of Faith – the most fundamental document in the history of the century-old denomination. https://cupandcross.com/chicagos-narragansett

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1953, p.23) – Pentecostal periodical content likely discussing church life or ministry in Narragansett.

- Christ’s Ambassadors Herald (July 1955, p.4) – Archive: Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center; Features youth or missions news where Narragansett likely appears in a report or story.

- Church of God Evangel (Aug 27, 1955, p.11) – Denominational publication with article or testimony likely involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1956, p.67) – Official minutes possibly documenting decisions or events relevant to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 28, 1956, p.4) – Article, testimony, or news about Pentecostal life connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 7, 1957, p.15) – News item, story, or report referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1957, p.14) – Narragansett likely cited in context of a church event or individual achievement.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1958, p.72) – Official record referencing Narragansett activities or personnel.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 21, 1958, p.15) – Article or news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1958, p.20) – Story or periodical piece potentially mentioning ministries in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1959, p.27) – Pentecostal news possibly about events in Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1960, p.82) – Minutes likely documenting decisions involving Narragansett churches or delegates.

- Church of God (Colored Work) Minutes (1960, p.156) – Record referencing Narragansett in the Black Pentecostal ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1961, p.26) – Ministry narrative or news about Narragansett participants or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1961, p.26) – Pentecostal update likely including Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1962, p.27) – Mission or church report involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 4, 1962, p.8) – Periodical item with church news or testimony from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1962, pp.24, 26) – Periodical articles likely covering events or ministries involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1962, pp.25, 27) – Reports or features about Narragansett in church or ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Sept 1962, p.27) – Commentary or report on Pentecostal work in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Sept 3, 1962, p.11) – Church publication news or testimony related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Dec 1962, p.25) – End-of-year feature or event report involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1963, pp.25, 27) – New Year ministry updates or personal narratives referencing Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Feb 1963, p.27) – Article tied to events or news about Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Apr 1963, p.27) – Ministry or personal story mentioning Narragansett’s Pentecostal activity.

- Lighted Pathway (May 1963, pp.24, 26) – Series of short reports or church updates involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 27, 1963, p.13) – Denominational article highlighting Narragansett members or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1963, pp.25, 26) – Monthly news or highlights referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 3, 1963, p.2) – Ministry or event news from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1963, p.26) – Summer reporting on church activity in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1963, p.26) – Monthly bulletin with Narragansett updates.

- Lighted Pathway (Oct 1963, p.26) – Late-year church life summary involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1963, p.26) – Ministry or church news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 4, 1963, p.23) – Publication sharing revival or missionary updates connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1964, p.98) – Official record documenting actions or ministers in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1964, p.25) – Early-year article involving outreach efforts within Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1964, p.25) – Summer feature mentioning ministry or youth activity from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 5, 1964, p.4) – Periodical covering sermon, testimony, or outreach from Narragansett.

- Church of God in Christ Women’s Int’l Convention Souvenir Journal (1966, p.33) – Biographical or feature mention related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1966, p.22) – Article focusing on community or youth ministry involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1968, p.22) – Church life feature reporting mission or revival activity linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1968, p.19) – Denominational story referencing Narragansett churches or workers.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1970, p.118) – Entry documenting leadership appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1974, p.266) – Proceedings referencing Narragansett ministry or district data.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 11, 1974, p.11) – Report detailing Pentecostal efforts or individuals from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Feb 24, 1975, pp.20–22) – Consecutive articles covering regional or missionary stories with Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 14, 1975, pp.18–21) – Cluster of related news items mentioning Narragansett connections.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1976, p.282) – Record noting organizational recognition involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1978, p.291) – Summary documentation listing Narragansett pastors or resolutions.

- Church of God Evangel (June 12, 1978, p.9) – News article or event centered on Pentecostal ministry in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 24, 1979, p.8) – Story or holiday report connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1980, p.308) – Record documenting proceedings or appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1982, p.327) – Assembly notes on activities or delegates linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1984, p.320) – Reference to ministry developments affecting Narragansett.

- Mission America Newsletter (Jan 1984, p.3) – Mission-focused newsletter item covering Narragansett outreach.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1988, p.387) – Record of ongoing ministry and leadership from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 1995, p.33) – Summer news or ministry highlights connected to Narragansett.

- Lee Review (2009, p.6) – Academic or reflective article mentioning Narragansett in theological context.

- Lee Review (2009, p.163) – Further academic commentary referencing Narragansett history.

- Church of God Evangel (Jan 2009, p.29) – Article or testimony on 21st-century Pentecostal activity in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 2011, p.19) – Year-end church reporting or testimony tied to Narragansett ministries.

- Living the Word: 125 Years of Church of God Ministry (2012, p.19) – Book excerpt referencing significant Narragansett milestones.

- Unto the Least of These: A History of Church of God Benevolence Ministries (2022, p.17) – Benevolence ministry history featuring Narragansett outreach.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.18) – Continuation highlighting Narragansett’s benevolence role.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.20) – Most current publication focusing on Pentecostal service and impact in Narragansett.

Prophetic Presence: The Sign of the Seers

For many years now, as a student of both Pentecostal theology and history, I have always wondered of the ever-present desire for Pentecostals to associate themselves with physical addresses. It is indeed strange, for as a movement of the Spirit we have always strived to remain on the go, being always persecuted or ever-changing as people of God. So I am astounded every time I come across a historic attempt to redefine our identity with a place or a location.

For many years now, as a student of both Pentecostal theology and history, I have always wondered of the ever-present desire for Pentecostals to associate themselves with physical addresses. It is indeed strange, for as a movement of the Spirit we have always strived to remain on the go, being always persecuted or ever-changing as people of God. So I am astounded every time I come across a historic attempt to redefine our identity with a place or a location.

The examples are many. From the very inception of the term “spirit-filled” people on the day of Pentecost, we have always associated our experience with an attempting to restore the identity of and struggled to return to the spiritual context in the experience of the Upper Room – a definite location in the city of Jerusalem. Then Paul, before ever answering his apostolic call and entering what would turn to a global ministry, was instructed to go the street called “Straight” – and this was not just a personal experience of Paul, but a corporate calling that includes the prophetic gift of another man and affected the future of the Early Church as we know it.

The early Pentecostal revivalists are best known with the name of Azusa Street, but not before establishing various locations across the country setting a spiritual rout, a geographic walkabout from the Bethel Bible College to the Santa Fe Mission, reaching the small house at 214 North Bonnie Brae Street and the Azusa Street Methodist Mission by 1906.

Synan records that there: “They shouted three days and three nights. It was Easter season. The people came from everywhere. By the next morning there was no way of getting near the house. As people came in they would fall under God’s power; and the whole city was stirred. They shouted until the foundation of the house gave way, but no one was hurt.”

But it was not until the morning of April 18, 1906 that the prophetic presence of the Azusa Street Pentecostal revival received its full recognition. Once the Great San Francisco earthquake hit California, just as early Pentecostals had prophesied, there was no need for preaching or witnessing any longer. Their prophetic presence was evidence in full. For the assigned geographical location for our vision contributes little to our identity in the ministry. It is a prophetic sign for the people we witness to. And this is a Biblical principle.

John the Baptist associated his ministry with the desert. John the Apostle, with the island called Patmos. The Old Testament prophet laid on his side for 390 long days being seen by all. That is one long year and one whole month according to the Jewish calendar. Then 40 days more on his other side, just like the bodies of the two prophets will lay dead for the three days of Revelation. The Seers were there, seeing the future and proclaiming it to the present through nothing less than a prophetic presence. For the Seers must be seen in order to reveal the vision they have seen in the Spirit, in order that both the world and church blinded by sin, can see the vision of the unseen and invisible God.

The Practice of Corporate Holiness within the Communion Service of Bulgarian Pentecostals

by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals (Research presentation prepared for the Society of Pentecostal Studies, Seattle, 2013 – Lakeland, 2015, thesis in partial fulfillment of the degree of D. Phil., Trinity College)

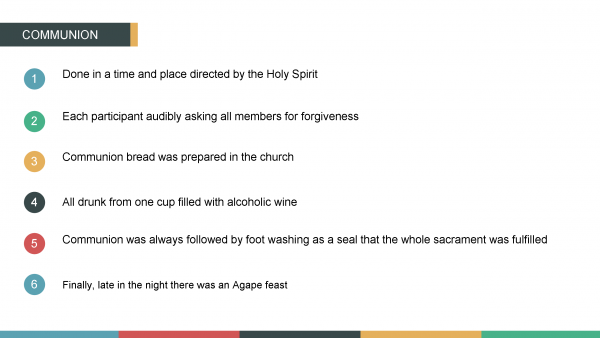

Pentecostal identity was corporately practiced and celebrated within the fellowship of believers through the partaking of Holy Communion. We have otherwise extensively described the Communion service among Bulgaria’s conservatives in Theology of the Persecuted Church (Part 1: Lord’s Supper https://cupandcross.com/theology-of-the-persecuted-church/). Therefore, here we offer just a brief overview of its main characteristics.

- It was done in a time and place directed by the Holy Spirit

- If some did not have water baptism they were taken to a close by river to be baptized while the rest of the church prayed

- Upon returning, if some did not have yet the baptism with the Holy Spirit, the church would pray until all were baptized

- It began with each participant audibly asking all members for forgiveness

- they would also audible respond with the words: WE FORGIVE YOU and may GOD also forgive you

- The communion bread was prepared on the spot baked by women whose names were also reveled in prayer

- All drank from one cup, which strangely for their strict practice of abstinence from alcohol, was filled with alcoholic wine

- Communion was served only to those who had the fullness of the Spirit, and had just requested and were given forgiveness

- The presbyter would quote Jude 20 to each partaking believer thus directing them to audibly speak in tongues before they could participate in communion

- Interpretation often followed to confirm the spiritual stand of the believer

- If there were any leftovers, the Communion elements were served again until all was used

- Communion was incomplete without foot washing as a seal that the whole sacrament was fulfilled.

Standing Firm in the Bible Belt Responding to a Resurgence of Witchcraft

Patricia Crowther passed away in September 2025 at the age of 97 from complications related to dementia. Crowther was one of the last direct cult-initiate of Gerald Gardner, often called the “father” of modern Wicca. For the past 75 years followers of Gardnerian Wicca have distorted truths teaching their beliefs as a spiritual path of reclamation, healing, and reverence for nature.

With her death, many adherents of modern paganism and witchcraft have felt motivated to interpret her passing as a moment of transitional resurgence. Her widespread hold has influenced new seekers and fringe groups to draw inspiration from her work, especially in places where spiritual vacuum or dissatisfaction with organized religion is strong.

In the rural parts of the Bible Belt like Tennessee, this phenomenon has posed particular challenges such as the following:

- Spiritual vulnerability: Some in isolated or economically struggling areas may be more open to alternative spiritualities if they feel the established church has failed them.

- Cultural tensions: Witchcraft or occult practices can intensify spiritual conflict, foster anxiety about “demonic influence,” or create fear and division in close communities.

- Distraction from the work of the Gospel: If congregations become preoccupied with spiritual warfare or defensive postures, that may drain resources from evangelism, discipleship, social outreach, and community care.

Thus, this death, rather than closing a chapter, may galvanize increased activity among her followers and deepen the spiritual battleground in regions already steeped in Christian faith. Prayer, fasting and standing firm with His light is the only force that will prevail against the darkness.

The Land of Pentecostals

A brief Interaction with Walter Brueggemann

by Dr. Dony K. Donev

Since I began studying Pentecostal history sometime ago, I have pondered the question of space and how we, Pentecostals, associate with it. Perhaps, on a larger scale, all Christian associate with space and location, but for Pentecostals it somehow becomes part of the identity of a given event, process or even person. This association is so strong that we simply cannot tell our history without it. And how is one even expected to tell Pentecostal history without places like the Bethel School of Healing, 214 Bonnie Brie Street and the Azusa Street Mission? Or how are we supposed to tell our story, to give our testimony of events significant and central for our spiritual life without a place and a location, which in most cases defines them all? For example, our salvation is connected the place where we were saved and sanctified; baptism with water or with fire from above; healing on the spot at a given prayer meeting, miracle service or church revival. And even eschatology, always undividable from the meeting in the clouds and the Heavenly city.

For Pentecostals, the Full Gospel teaching is a covenant theology because it ultimately subscribes to the quest for the Promised Land. But, I’ve never been able to pin point the reasoning behind this until reviewing anew Brueggemann’s study of “The Land” and comparing his ideas with Pentecostal history and praxis through the following quotes that will exchange perspectives with the questions stated above and hopefully stir further thinking.

p.5 “Space” means an arena of freedom without coercion or accountability, free of pressure and void of authority. …. But “place” is a very different matter. Place is space which has historical meanings, where some things have happened which are now remembered and which provide continuity across generations. Place is space in which important words have been exchanged, which have established identity, defined vocation, and envisioned destiny. Place is space in which vows have been exchanged, promises have been made, and demands have been issued. Place is indeed a protest against unpromising pursuit of space. It is a declaration that our humanness cannot be found in escape, detachment, absence of commitment, and undefined freedom.

Whereas pursuit of space may be a flight from history, a yearning for a place is a decision to enter history with an identifiable people in an identifiable pilgrimage.”

p. 11 “The very land that promised to create space for human joy and freedom became the very source of dehumanizing exploitation and oppression. Land was indeed a problem for Israel. Time after time, Israel saw the land of promise become the land of problem.”

p. 15 “….land theology in the Bible: presuming upon the land and being expelled from it; trusting toward a land not yet possessed, but empowered by anticipation of it.”

p. 27 “The action is in the land promised, not in the land possessed … So Jacob, bearer of the promise, is buried in Canaan under promise.”

p. 42 “Presence is for pursuit of the promise …. The new people, contrasted with the old, are promise-trusters, rooted in Moses, linked to the faith of Caleb, and identified as the vulnerable ones. His presence is evident in his intervention not to keep things going, but to bring life out of death, to call to himself promise-trusters in the midst of promise-doubters.”

p. 47 “Israel knew that in his speaking and Israel’s hearing was its life. That is why the first word in Israel’s life is “listen” (Deut. 6:4)! Israel lived by a people-creating word spoken by this people-creator (Deut. 8:3).”

p. 51 “Both rain and manna come from heaven, from outside the history of coercion and demand.”

p. 53 “Israel does not have many resources with which to resist the temptation. The chief one is memory. At the boundary [of Gilgal] Israel is urged to remember …. Remembering is an historic activity. To practice it is to affirm one’s historicity.”

p. 54 “Land can be a place for historical remembering, for action that affirms the abrasive historicity of our existence. But land can also be, as Deuteronomy saw so clearly, the enemy of memory, the destroyer of historical precariousness. The central temptation of the land for Israel is that Israel will cease to remember and settle for how it is and imagine not only that it was always so but it will always be so. Guaranteed security dulls the memory …. Israel’s central temptation is to forget and so cease to be a historical people, open either to the Lord of history or to his blessings yet to be given. Settled into an eternally guaranteed situation, one securely knows that one is indeed addressed by the voice of history who gives gifts and makes claims. And if one is not addressed, then one does not need to answer. And if one does not answer, then one is free not to care, not decide, not to hope and not to celebrate.”

p. 56 “The land will be avenged preciously because land is not given over to any human agent, but is a sign and function in covenant. Thus arrayed against the monarchy are both the traditionalism of Naboth and the purpose of Yahweh.”

p. 57 “Israel finds itself in history as one who had no right to exist. Slaves become an historical community. Sojourners become secured in land …. Non of it achieved, all of it given …. And the way to sustain gifted existence is to stay singularly with the gift-giver.”

And the following conclusions: as Pentecostals, we associate with places and location, we ultimately associate with land as part of our covenant theology, because:

1. In the land we place our own historical meaning, our part and role in history, as well as the spiritual heritage we have received and we give to a next generation; thus, place itself becomes not only where our history happens, but a defining part of our historical identity as a people.

2. Enduring the promise of a land not yet seen, but already received by faith, has indeed been the formative factor in any and all Pentecostal movements around the globe, as well as the initiative to restore the social order for peoples whose land has been taken away unfairly. We have even learned, that when the Promised Land becomes a land of problem, we must return to the promise in order to remain a movement after the move of the Holy Ghost and not merely a nominal denomination.

3. As humans, we localize the omnipresence of God to the place of our experience with God – the place where God has become personal for us. And this is the place, where we dare say, we have received the promise of God. Although His promise may not yet be visible in reality, having come from our experience with God, it creates a reality which is much more real than the present reality. In that sense, the very act of receiving the promise that comes from outside of history and through hearing the voice of God, recreates our reality and future.

4. Main, among other temptations for us, is the temptation to forget the land, the place of promise and meeting with God – where we come from, where we have been and where we are going. Just as Israel, this act of forgetting denotes our ceasing from being a historical people.

5. And just like Israel did, Pentecostals find themselves without the right to exist. Yet, the association with the land, and not merely any land but the Land of Promise, gives us not only a right of existence, but also an identity which no one, not even us, can change or redefine, except the Giver of the Promise. And this is the function of the covenant and the association of our personal experience with God to a place, a location, a spot in history where our lives were once and for all changed for eternity.