BLACK FRIDAY BOOK SALE

All books by Cup&Cross on SALE

Final clearance sale for the year with new titles coming up in early 2021

CLICK the picture below to view all titles on Amazon.com

COVID and the AMPA receptors of the brain

The conversation began by highlighting the ongoing impact of long COVID, specifically focusing on individuals who continue to experience symptoms like brain fog long after the pandemic’s initial phases. A recent study published in Brain Communications provided the first biological evidence explaining this phenomenon. Researchers discovered changes in AMPA receptors of the brain, which are crucial for memory and learning, potentially linking these changes to cognitive impairments commonly associated with long COVID. Utilizing cutting-edge PET imaging, the study compared brain scans of those with long COVID to those without, revealing increased AMPA receptor densities in affected individuals.

Dr. Deepak Nair pointed out that the study’s findings were intriguing, noting that those with brain fog showed an upregulation of AMPA receptors, linking this to possible cognitive function decline. However, the findings suggest that increased AMPA activity is only part of the picture; an overactive immune response in the brain, potentially triggered by COVID infections, might also contribute. Researchers identified inflammatory markers that coincided with increased AMPA receptor levels, indicating that these immune responses might underlie the receptor changes and associated cognitive issues.

Despite these promising insights, the study remains in its early stages. Dr. Nair highlighted the need for additional context, such as the COVID status of the control group, to further validate the results. While the study did not propose a specific treatment, it offers a direction for scientists to explore, such as developing medications targeting AMPA receptor activity to help alleviate brain fog symptoms. According to Dr. Takuya Takahashi, recognizing brain fog as a legitimate condition could inspire the healthcare industry to develop better diagnostic tools and treatments, offering hope to those still battling the long-term effects of COVID-19.

Dony Donev: Theological Work in Pentecostal Studies

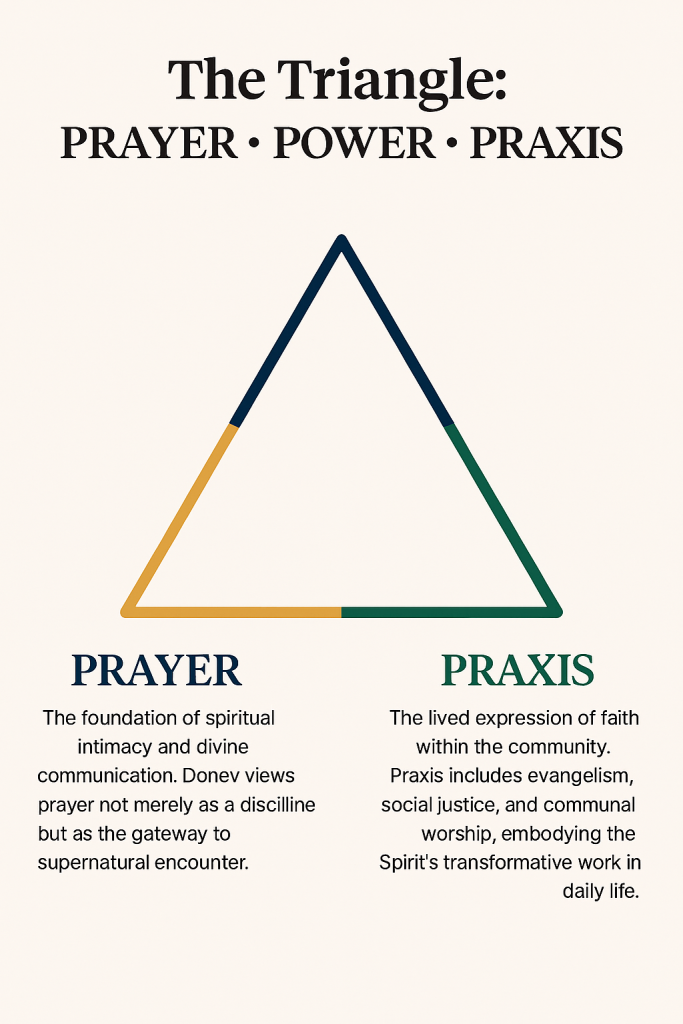

Dony Donev is known for his theological work, particularly in the context of Pentecostal studies. While he may not have a widely recognized catalog of specific terms or frameworks that have achieved broad usage, he has contributed significantly to the academic field through his research and writings.

Theological Contributions

-

Pentecostal Studies: Donev’s work often focuses on Pentecostal theology, examining its historical development, doctrinal distinctives, and contemporary implications.

-

Contextual Theology: He explores how Pentecostal theology interacts with cultural and societal contexts, particularly in Eastern Europe.

-

Pentecostal Hermeneutics: Donev might have contributed to discussions about how Pentecostals interpret the Bible, emphasizing a Spirit-led reading of the Scriptures.

Key Terms or Concepts

-

Emerging Pentecostal Identity: A possible area of focus where Donev discusses how Pentecostal identities are evolving in the modern world, including how they reconcile traditional beliefs with contemporary contexts.

-

Cultural Engagement: A term that may be used to describe his analysis of Pentecostalism’s role in engaging with and transforming culture.

For more specific terms or frameworks coined by Dony Donev, it would be beneficial to consult his published works or academic papers.

Pentecostal primitivism is a concept within Pentecostal theology emphasizing a return to the faith and practices of the early Christian church. Here’s an overview:

Key Aspects of Pentecostal Primitivism

Restoration of Apostolic Practices

- Focus on Original Christianity: Emphasizes the imitation of New Testament church dynamics, including spiritual gifts.

- Spirit-Led Worship: Encourages direct experiences with the Holy Spirit, akin to early church practices.

Doctrinal Simplicity

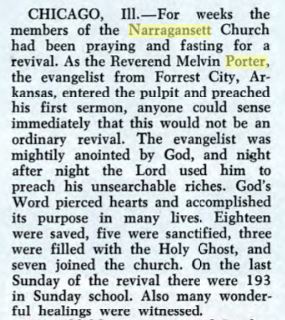

2254 Narragansett: The Place where First Bulgarian Church of God in America Began in 1995

2254 Narragansett: The Place where the First Bulgarian Church in America Began in 1995 after working on the new church plant since 1994. With a sequence of startup events including a July 4th block party and Bulgarian picnic, first official services in Bulgarian language was held on July 10, 1995. With over a dozen Bulgarians present at 1 PM that memorable Sunday, Rev. Dony K. Donev delivered a the first message for the newly established congregation from Genesis ch. 18.

Narraganset holds a significant place in Church of God (Cleveland, TN) history. Narraganset Church of God was started by a women-preacher with only 10 members. Rev. Amelia Shumaker started the church only 15 days before the Great Depression began in 1929. https://cupandcross.com/90-years-ago

Rev. James Slay of the Narragansett Church of God in Chicago was commissioned to write the 1948 Church of God Declaration of Faith – the most fundamental document in the history of the century-old denomination. https://cupandcross.com/chicagos-narragansett

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1953, p.23) – Pentecostal periodical content likely discussing church life or ministry in Narragansett.

- Christ’s Ambassadors Herald (July 1955, p.4) – Archive: Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center; Features youth or missions news where Narragansett likely appears in a report or story.

- Church of God Evangel (Aug 27, 1955, p.11) – Denominational publication with article or testimony likely involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1956, p.67) – Official minutes possibly documenting decisions or events relevant to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 28, 1956, p.4) – Article, testimony, or news about Pentecostal life connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 7, 1957, p.15) – News item, story, or report referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1957, p.14) – Narragansett likely cited in context of a church event or individual achievement.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1958, p.72) – Official record referencing Narragansett activities or personnel.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 21, 1958, p.15) – Article or news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1958, p.20) – Story or periodical piece potentially mentioning ministries in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1959, p.27) – Pentecostal news possibly about events in Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1960, p.82) – Minutes likely documenting decisions involving Narragansett churches or delegates.

- Church of God (Colored Work) Minutes (1960, p.156) – Record referencing Narragansett in the Black Pentecostal ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1961, p.26) – Ministry narrative or news about Narragansett participants or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1961, p.26) – Pentecostal update likely including Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1962, p.27) – Mission or church report involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 4, 1962, p.8) – Periodical item with church news or testimony from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1962, pp.24, 26) – Periodical articles likely covering events or ministries involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1962, pp.25, 27) – Reports or features about Narragansett in church or ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Sept 1962, p.27) – Commentary or report on Pentecostal work in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Sept 3, 1962, p.11) – Church publication news or testimony related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Dec 1962, p.25) – End-of-year feature or event report involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1963, pp.25, 27) – New Year ministry updates or personal narratives referencing Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Feb 1963, p.27) – Article tied to events or news about Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Apr 1963, p.27) – Ministry or personal story mentioning Narragansett’s Pentecostal activity.

- Lighted Pathway (May 1963, pp.24, 26) – Series of short reports or church updates involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 27, 1963, p.13) – Denominational article highlighting Narragansett members or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1963, pp.25, 26) – Monthly news or highlights referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 3, 1963, p.2) – Ministry or event news from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1963, p.26) – Summer reporting on church activity in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1963, p.26) – Monthly bulletin with Narragansett updates.

- Lighted Pathway (Oct 1963, p.26) – Late-year church life summary involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1963, p.26) – Ministry or church news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 4, 1963, p.23) – Publication sharing revival or missionary updates connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1964, p.98) – Official record documenting actions or ministers in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1964, p.25) – Early-year article involving outreach efforts within Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1964, p.25) – Summer feature mentioning ministry or youth activity from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 5, 1964, p.4) – Periodical covering sermon, testimony, or outreach from Narragansett.

- Church of God in Christ Women’s Int’l Convention Souvenir Journal (1966, p.33) – Biographical or feature mention related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1966, p.22) – Article focusing on community or youth ministry involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1968, p.22) – Church life feature reporting mission or revival activity linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1968, p.19) – Denominational story referencing Narragansett churches or workers.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1970, p.118) – Entry documenting leadership appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1974, p.266) – Proceedings referencing Narragansett ministry or district data.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 11, 1974, p.11) – Report detailing Pentecostal efforts or individuals from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Feb 24, 1975, pp.20–22) – Consecutive articles covering regional or missionary stories with Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 14, 1975, pp.18–21) – Cluster of related news items mentioning Narragansett connections.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1976, p.282) – Record noting organizational recognition involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1978, p.291) – Summary documentation listing Narragansett pastors or resolutions.

- Church of God Evangel (June 12, 1978, p.9) – News article or event centered on Pentecostal ministry in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 24, 1979, p.8) – Story or holiday report connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1980, p.308) – Record documenting proceedings or appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1982, p.327) – Assembly notes on activities or delegates linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1984, p.320) – Reference to ministry developments affecting Narragansett.

- Mission America Newsletter (Jan 1984, p.3) – Mission-focused newsletter item covering Narragansett outreach.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1988, p.387) – Record of ongoing ministry and leadership from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 1995, p.33) – Summer news or ministry highlights connected to Narragansett.

- Lee Review (2009, p.6) – Academic or reflective article mentioning Narragansett in theological context.

- Lee Review (2009, p.163) – Further academic commentary referencing Narragansett history.

- Church of God Evangel (Jan 2009, p.29) – Article or testimony on 21st-century Pentecostal activity in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 2011, p.19) – Year-end church reporting or testimony tied to Narragansett ministries.

- Living the Word: 125 Years of Church of God Ministry (2012, p.19) – Book excerpt referencing significant Narragansett milestones.

- Unto the Least of These: A History of Church of God Benevolence Ministries (2022, p.17) – Benevolence ministry history featuring Narragansett outreach.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.18) – Continuation highlighting Narragansett’s benevolence role.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.20) – Most current publication focusing on Pentecostal service and impact in Narragansett.

The Digital Ecclesia: A Theological Exploration

In the contemporary ecclesial landscape, the Seventh-day Adventist Church stands at a pivotal juncture, grappling with the imperatives of the Great Commission in a digital age. The biblical mandate to “go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation” (Mark 16:15, NIV) resonates profoundly in an era where approximately 42% of the global population engages with social media, as noted in mid-2019 data. This thesis posits that digital communications, far from being a peripheral tool, represent a divinely ordained extension of the apostolic mission, akin to the School of Tyrannus in Ephesus where Paul’s teachings “went viral” through oral dissemination (Acts 19:8-10, NASB). Drawing from personal ecclesial campaigns and broader theological reflections, this essay argues that transforming digital influence into global impact necessitates a paradigm shift from linear evangelism models to holistic, empathetic digital discipleship. By integrating scriptural precedents, empirical evidence from church initiatives, and case studies, we explore how the Church can leverage digital tools to reach the “unreachable,” foster cultural empathy, and cultivate disciples who embody Christ’s relational ethos. This analysis underscores the theological imperative for strategic digital engagement, ensuring the gospel permeates intersecting cultures in both virtual and physical realms.

The Theological Foundation of Digital Influence as Missional Extension: Theologically, digital communications echo the incarnational ministry of Christ, who met people where they were, adapting to their cultural paradigms (1 Corinthians 9:19-23, NASB). The text under examination illustrates this through a 2016 campaign for the “Your Best Pathway to Health” mega-health clinic in Beckley, West Virginia, Appalachia—a region stereotyped as technologically disconnected. With a modest $200 budget, targeted Facebook ads reached 200,000 users within a 50-mile radius, outperforming traditional media like flyers and newspapers in exit surveys. Testimonials revealed that online ads prompted offline sharing: family members and friends, not on social media, were informed and attended, embodying the Samaritan woman’s evangelistic zeal (John 4:28-30, NIV).This case study provides empirical proof of digital tools’ amplification power. A New York Times study cited in the text affirms that 94% of people share online content to improve others’ lives, aligning with human nature’s propensity for communal benevolence. Theologically, this mirrors the early Church’s organic spread: Paul’s stationary ministry in Ephesus disseminated the gospel across Asia via travelers who “liked and shared” his message verbally, reaching Jews and Greeks alike (Acts 19:10). In modern terms, social media serves as the “modern School of Tyrannus,” a digital agora for idea exchange. Evidence from the Beckley campaign demonstrates that targeting the connected 42% activates networks bridging to the 58% offline, challenging assumptions of digital irrelevance in underserved areas. The author’s personal rebuttal to a friend’s skepticism—rooted in data over presumption—highlights ecclesial resistance to innovation, yet the results validate a Pauline strategy scaled by technology: reach the reachable to evangelize the unreached.

With members spanning nations, tribes, and tongues, digital tools empower diaspora connections. For isolated communities, the text invokes the Holy Spirit’s sovereignty, recalling Mark 16:15’s call not as human achievement but divine partnership. This theological framework—evangelism as relational sharing—counters secular digital marketing’s transactionalism, emphasizing discipleship’s transformative ethos. The Beckley initiative’s success, where social media rivaled word-of-mouth referrals, proves that digital influence transcends virtual boundaries, fostering real-world attendance and healing, thus fulfilling the Church’s wholistic mission of body and soul.

From Linear Paths to Journey Loops: Reimagining the Seeker’s Spiritual Pilgrimage

Traditional evangelism’s linear funnel—from awareness to membership—mirrors outdated marketing but falters in a post-modern, multicultural world of “intersecting cultures.” The text critiques this model, advocating a “Seeker’s Journey” with non-linear loops: “See” (Awareness), “Think” (Consideration), “Do” (Visit/Engage), “Care” (Relationship/Service), and “Stay” (Loyalty/Membership). This systems-thinking approach, drawing from Margaret Rouse’s definition of interrelated elements achieving communal goals, reflects the Holy Spirit’s dynamic work, not mechanistic conversion.

Proof emerges from the modified digital funnel, integrating traditional and digital strategies. Exposure via organic traffic, ads, and word-of-mouth feeds discovery, where seekers consume content and assess relevance. Consideration evaluates “digital curb appeal,” leading to engagement—visits, Bible studies, or prayer requests. Relationship-building through empathetic follow-up and text evangelism sustains loyalty, looping disciples back as creators and engagers. A case study implicit in the text is the author’s transition from secular marketing to church application: pre-clinic prayers yielded testimonies of digital-driven attendance, with social media second only to personal referrals. This evidences the funnel’s efficacy, where engagers span touchpoints, building bridges from online anonymity to in-person commitment.

Theologically, this resonates with Paul’s adaptability: “I have become all things to all people, that by all possible means I might save some” (1 Corinthians 9:22, NIV). In a world of migrants and global connections, even static communities like the author’s Appalachian hometown—lacking cell reception yet tied via satellite—illustrate digital reach. The text’s personal anecdote of introducing Adventism to parents through conversations exemplifies empowering insiders: migrants from remote areas, digitally connected, share culturally attuned gospel messages upon return visits. Data from Pew underscores Adventism’s diversity as a missional asset, yet untapped digitally. The journey loops counter assumptions of homogeneity, promoting cultural empathy—empowering community members as evangelists, much like the Ethiopian eunuch’s self-directed study via Philip’s guidance (Acts 8:26-40). By magnifying friendship evangelism, digital tools enable 24/7 kingdom pursuit, measuring success not by pew counts but disciple formation, echoing Jesus’ relational model over programmatic faith.

Cultivating Cultural Empathy: Audience Personas and Generational Dynamics in Ecclesial Outreach

Effective digital evangelism demands “cultural empathy,” expanding culture beyond geography to encompass platforms, generations, and identities. The text warns against “Adventist-speak” barriers, urging internal (church members) versus external (community) vernacular distinctions. Personas—fictional archetypes blending demographics, needs, and values—humanize audiences, fostering resonance. For instance, “Bryce,” a 17-year-old Hispanic Adventist college aspirant, embodies challenges like rejection and doubt, valuing diversity and mentorship. Messages like “We are all adopted into God’s family” address his core, proving personas’ evangelistic utility.Empirical evidence from surveys and analytics validates this: deeper connections via shared experiences transcend surface demographics, yielding loyalty. The text’s framework—surface (age, location) to deep (needs like spiritual community, justice)—aligns with 1 Corinthians 9’s missional flexibility. A key case study is Generation Z (1997-2012), the least religious cohort per Pew, with 35% unaffiliated and short attention spans favoring visuals over text. Yet, 60% seek world-benefiting work and 76% environmental concern, presenting opportunities for a “social gospel” of action. The iPhone’s primacy in their historical narrative underscores technology’s reshaping of connection, demanding Church innovation. Millennials, similarly departing, highlight the urgency: without adaptation, institutions risk obsolescence, as W. Edwards Deming quipped, “Survival is not mandatory.”

Theologically, this echoes Ecclesiastes 1:9-11’s cyclical generations, analyzed in Pendulum by Williams and Drew. The current “We” swing (peaking 2023) favors authenticity, teamwork, and humility over “Me” individualism. Examples include L’Oréal’s slogan shift from “I’m worth it” to “You’re worth it,” and the U.S. Army’s “Army Strong” emphasizing collective resilience. Gorgeous2God, a youth ministry tackling rape and depression candidly, exemplifies “We” values: 45,000 social followers and 20,000 annual website visitors stem from transparent storytelling, disarming via “self-effacing transparency.” This counters Church sluggishness, empowering youth as generational evangelists. By unpacking intersecting cultures—e.g., immigrants versus transplants—the Church bridges gaps, fulfilling Revelation 7:9’s multicultural vision. Personas and empathy ensure messages resonate, turning digital platforms into loci of divine encounter

Strategic Implementation: Tools, Teams, and Metrics for Ecclesial Digital StewardshipDigital tools—social media, email, podcasts, SEO—democratize gospel dissemination, yet require strategic stewardship. The text defines them as binary-processed devices enabling instantaneous global connection, integral for local mission in secular North America. With 1.2 million Adventists across 5,500 churches, untapped potential abounds: digital amplifies relationships, revealing felt needs for targeted service.

The Digital Discipleship and Evangelism Model integrates creators (content packaging), distributors (promotion), and engagers (relational dialogue), holistically scaling traditional evangelism. A sample Digital Bible Worker job description illustrates: responsibilities include content calendars, ads, livestreamed studies, and mentoring, bridging digital to in-person. Case evidence: youth spending 9-18 screen hours daily affords entry at their comfort, anonymity fostering trust.

Leadership must audit platforms, analyze data, and set KPIs—activity (posts), reach (impressions), engagement (shares), conversion (baptisms), retention (testimonials). The “Rule of 7” mandates multi-channel reinforcement amid 3,000 daily ad exposures. Budgets scale: $300 locally yields community awareness; $3,000 nationally drives impact. Batch-scheduling via calendars ensures proactivity, as in the Beckley campaign’s data-driven targeting.

Theologically, this stewards talents (1 Corinthians 12), empowering youth and “social butterflies” in multi-generational teams. Training counters silos, ensuring seamless online-offline continuity. Metrics prioritize kingdom growth over metrics, echoing Jesus’ parables of patient sowing (Mark 4:26-29). By serving needs first—”People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care”—digital strategies build trust, inviting gospel response.

Conclusion: This ecclesial theological inquiry affirms digital influence’s transformative potential for global impact, rooted in scriptural relationality and evidenced by campaigns like Beckley. From journey loops to empathetic personas, strategic tools empower the diverse Adventist body to fulfill Mark 16:15 digitally. Challenges—assumptions, generational shifts—yield to Holy Spirit-led adaptation, as Paul’s Ephesian model scaled virally. Churches must audit, train, and budget intentionally, measuring disciple depth over breadth. Ultimately, digital evangelism incarnates Christ’s empathy, turning virtual connections into eternal kingdom harvests. As we commit to two years of faithful sharing—like Paul—the gospel will proliferate, proving no limitation on the Spirit in our hyper-connected age. The Church, as movement not institution, thrives by embracing this digital mandate, ensuring every nation hears the good news.

Theological Reflections on Dubai as a Modern-Day Babylon: An Analysis of Prophetic Parallels

Theological Reflections on Dubai as a Modern-Day Babylon: An Analysis of Prophetic Parallels

I present this discussion to address an intriguing observation that has surfaced after over two decades of preaching on eschatological signs around the world. While I have delivered messages on the potential parallels between biblical prophecy and contemporary developments, including the rise of Dubai as a possible modern-day iteration of Babylon, I find that there is an absence of an English-language recording encapsulating these ideas. Although materials exist in Bulgarian and other languages, their accessibility requires translation—a process akin to the biblical “gift of interpretation of tongues” (1 Corinthians 12:10). Today, I endeavor to provide a concise analysis of how biblical prophetic frameworks align with the socio-economic and cultural developments in Dubai, with a particular focus on its potential typological significance as a restored Babylonian empire.

The 10-Nation Confederation and Its Eschatological Implications

To begin, we observe the existence of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), a 10-nation consortium that includes Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The composition of this organization is noteworthy for its shared Islamic identity, which imbues its geopolitical actions with apocalyptic undertones, as noted by Esposito (1999) in The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality?. Within Islamic eschatology, the concept of the Mahdi, a messianic figure, plays a central role, and population growth is often viewed as a religious imperative to strengthen the Muslim world’s global influence (Nasr, 2007). This shared worldview situates the Middle East, and particularly Dubai, as a focal point in contemporary discussions of global power shifts.

Economic and Cultural Hegemony of Dubai

Dubai, strategically located across the Persian Gulf from Iraq, resonates with the ancient descriptions of Babylon as a center of wealth, trade, and cultural exchange. Scholars such as Oster (2017) have highlighted that ancient Babylon was not merely a geographic entity but a symbol of hubristic human ambition and economic dominance, themes that echo in the modern emirate’s meteoric rise. Dubai hosts over 25 million tourists annually and boasts one of the largest airports in the world, positioning itself as the “tourism capital of the world” (UNWTO, 2023). Additionally, Dubai’s multicultural fabric, where representatives from virtually every nation, language, and religion coexist, aligns with the biblical depiction of Babylon as a cosmopolitan hub (Revelation 17:15).

Economically, Dubai’s influence extends far beyond its borders. It controls over 30% of the NASDAQ technical index, reflecting its significant role in global financial markets (Jones, 2022). The construction of man-made islands, such as Palm Jumeirah and “The World,” symbolizes both its technological prowess and its aspiration to reshape the natural world—a characteristic often attributed to ancient Babylon’s monumental architecture (Finkel, 2013).

Biblical and Historical Comparisons

Theologically, parallels between Dubai and ancient Babylon can be drawn from the narrative of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11. The construction of the Tower was motivated by human vanity and a desire to “make a name for ourselves” (Genesis 11:4, NIV), a sentiment that mirrors Dubai’s rapid urbanization and global branding efforts. Furthermore, the Etemenanki ziggurat in Babylon, dedicated to the god Marduk, served as a “temple of the foundation of heaven and earth” (George, 1992). Similarly, Dubai’s architectural marvels, such as the Burj Khalifa—the tallest building in the world—serve as modern testaments to human ambition and ingenuity, echoing ancient aspirations to connect the terrestrial with the divine.

From a historical perspective, the Tower of Babel was constructed after the biblical flood (Genesis 6-9), ostensibly as a safeguard against future cataclysms. This raises the question: Is Dubai, with its advanced infrastructure and resilience to climate change, similarly positioned as a haven against potential global crises? While speculative, this analogy invites further exploration through interdisciplinary studies of theology, urban planning, and environmental sustainability.

Eschatological Considerations and Future Directions

Critics argue that comparisons between Dubai and Babylon lack theological significance. However, an examination of the facts reveals compelling parallels. Scholars such as Beale (1999) have emphasized the symbolic role of Babylon in biblical prophecy, representing human rebellion against divine authority and the concentration of power, wealth, and corruption. Dubai’s emergence as a dominant force in the global economy and culture invites reflection on whether it fulfills a similar archetype in contemporary times.

Finally, the rise of new economic alliances, such as BRICS and the shift toward alternative currencies for oil trade, further underscores the Middle East’s centrality in shaping global geopolitics (Shah, 2023). As the region continues to evolve, the potential for a unified Arab political and economic bloc reminiscent of ancient Babylon remains a topic of significant scholarly interest.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while Dubai is not a direct geographical or historical successor to Babylon, its symbolic resonance with the ancient city is undeniable. The intersection of biblical prophecy, economic power, and cultural diversity renders Dubai a compelling case study for understanding the eschatological dynamics of the modern world. As history unfolds, it remains to be seen whether Dubai will further solidify its role as a modern Babylon, embodying the themes of ambition, globalization, and apocalyptic anticipation that have captured the human imagination for millennia.

Gustavo Gutiérrez’s Mysticism as a Door to Pentecostal Dialogue

Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Te Movement Toward Mysticism in Gustavo Gutiérrez’s Tought: Is Tis an Open Door

to Pentecostal Dialogue?

Joseph Davis

Associate Professor of Religion, Southeastern University, Lakeland, Florida

Abstract

Over the last few years a distinct shift has occurred within the thought of liberation theology’s most famous proponent, Gustavo Gutiérrez. Specifically, Gutiérrez has ventured into mysticism. With this movement a fascinating question can be posed: Does the incorporation of mysti- cism open up a door for dialogue with Latin America’s other popular theology, Pentecostalism? Conversely, should Pentecostalism reflexively understand itself historically and theologically as a liberating movement of the poor? Placed together, an emphasis on praxis seems to reveal, at minimum, a common starting point. Te methodology of the paper incorporates a detailed historical analysis of Gutiérrez’s position on mysticism and moves to the conclusion that the shift in emphasis opens the door, albeit a small crack, to one of the most exciting opportuni- ties to occur within the history of Christianity: the marriage of Pentecostal spirituality with liberating social action.

Keywords

Gustavo Gutiérrez, liberation theology, mysticism, Pentecostalism

At the 2008 Society for Pentecostal Theology conference, Jürgen Moltmann made a startling statement to commence his talk on the work of “Pentecostals and Liberation Teology.” He said, “I met with Gustavo Gutiérrez in Lima a few years ago, and as we were talking he looked out his window and pointed to the barrios below saying, ‘Out there, it is the Pentecostals who are going into the barrios [to reach the poor].”1 What Gutiérrez meant by the statement was that despite the divide that had separated the two most dominant camps of religious fervor within Latin America, the evidence was clear: it was the

1

Jürgen Moltmann, Statement made at Society for Pentecostal Theology, 15 March 2008, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2011 DOI: 10.1163/157007411X554668

1

6

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Pentecostals who were helping the poor. Laden within such a statement are a plethora of both endless possibilities and admittedly speculative projections. In fact, at the onset one must admit that one small statement does not equate to a full-blown theological tour de force. Nor does it mean that the wedding ceremony is about to begin to join these two previously disparate antagonists. What this statement does create, however, is an open door to further scholarly reflection. Tis is particularly true if the aforementioned statement is coupled with perceived changes in Gutiérrez’s stance toward a kindred spirit of Pente- costalism, namely, mysticism. Granted, mysticism is not Pentecostalism and Pentecostalism is not mysticism.2 But it would not be too much to say that there are similarities between the two, and any movement toward the one may have broader ranging implications for the other. Terefore, before venturing further in fruitless conjecture, a number of questions must be answered. First, have there been any changes in Gutiérrez’s theology of liberation that warrant such projections? Tere are some who feel that all talk of change within Gutiér- rez’s theology of liberation is a misunderstanding of his thought.3 Second, what is Gutiérrez’s approach to mysticism? And third, is it possible that praxis itself has created a crack in the door within Gutiérrez’s thought that might integrate two seemingly disparate theologies? Of course, these questions do not stop at Latin America; rather, the prospect of such a provocative fusion has worldwide implications.

Over the past half-century primarily two religious movements have gripped the imaginations and aspirations of the poor in Latin America. Tose two movements are the theology of liberation and the Pentecostal movement.4 Of the two, only liberation theology can be truly said to be indigenous in origin. Pentecostalism is indigenous in another manner; it is the overwhelming choice of the poor in Latin America.5 Daniel Chiquete, commenting on the perceived rise of Protestantism, denied this misunderstanding by retorting that Latin America has not turned Protestant at all; rather, “Latin America has turned

2

Simon Chan has made an interesting case for a structural compatibility between the two. See Simon Chan, “Pentecostal Teology and Christian Spiritual Tradition,” Journal of Pentecostal Teology Supplement Series 21 (2000).

3

One of Gutiérrez’s most recent biographers, James Nickoloff, maintains such a conservative position. See James B. Nickoloff, “A Future for Peru? Gustavo Gutiérrez and the Reasons for His Hope,” Horizons 19 (Spring 1992): 31-43.

4

Te Pentecostal movement originated at the Azusa Street Revival in 1906. Most point to the Medellín Conference in 1968 as the beginning of the liberation theology movement.

5

Laurie Goodstein, “Pentecostal and Charismatic Groups Growing,” New York Times, 6 Octo- ber 2006.

2

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

7

Pentecostal!”6 In his book on Pentecostalism, Allan Anderson confirms this by saying, “Te growth of Pentecostalism in Latin America has been one of the most remarkable stories in the history of Christianity.”7 In fact, a Templeton grant research project confirmed these observations. In terms of the world’s population, two of the top three countries with the largest percentage of Char- ismatics/Pentecostals are in Latin America.8

Interestingly enough, the tie between Pentecostalism and the poor in Latin America is not a local aberration. Te history of Pentecostalism reveals that a disproportionate number of dispossessed and poor are attracted to its message of a God whose Spirit is active and fully invested in the present. Juan Sep- ulveda notes, “From a statistical point of view, Pentecostalism has spread far more in the lower classes of popular sections of Latin American societies” than in the upper or middle classes of society.9 In fact, recent studies confirm not just an interest among the Hispanic poor in the “spiritual” aspects of faith but also a commitment among Hispanic Pentecostals for social change.10 Why? Te answer lies both in Pentecostalism’s derivation and its foundational thesis that God can speak to the common person of any nation, tongue, or tribe. Chiquete notes, “By their very nature the Pentecostals are natural promoters of plurality and inner-cultural contact.”11 In the Azusa Street Revival, one finds the message of a God active in history born among the poor and racially, sexually (gender), and economically dispossessed. From the movement’s inception, Pentecostals were the people “from the other side of the tracks.” Yet, in spite of these humble roots, the exportation of Pentecostalism to Latin America was often viewed with a jaundiced eye among the local religious intelligentsia. Given its origin in the United States, Pentecostalism was sus- pected of being tinged with imperialism.12 As a result, the missions-centered

6

Daniel Chiquete, “Latin American Pentecostalism and Western Modernism: Reflections of a Complex Relationship,” International Review of Mission 92, no. 364 (2003): 38.

7

Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 63.

8

Tirty-four percent of the population of Brazil and 40 percent of the population of Guate- mala are Pentecostal/Charismatic worshippers. Te Pew Forum, 6 October 2006.

9

Juan Sepulveda, “Future Perspectives for Latin American Pentecostalism,” International Review of Mission 87 (April 1998): 191.

10

Villafane points out that Pentecostals in the Hispanic community in New York City are at the forefront of social concern and outreach. See Eldin Villafane, Te Liberating Spirit: Toward an Hispanic American Pentecostal Social Ethic (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1993), 110-26.

11

Chiquete, “Latin American Pentecostalism and Western Modernism,” 36.

12

Sepulveda refutes this conception, saying, “Te commonly held accusation that the rapid growth of Latin American Pentecostalism is the result of a sort of conspiracy of the U.S.

3

8

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Pentecostalism exported to Latin America had the label, “Made in America.” Te label should have read more correctly, “Made among the Poor and Dis- possessed of America.” Here, in Pentecostalism, was a movement that began with the poor and contained in its origins the foundational tenets of breaking down the barriers of social, racial, and gender classifications.

Te early Gutiérrez was clearly one of the students of Latin American theol- ogy who viewed any importation of religion from capitalistic countries with caution. He notes, “Te history of Christianity, too, has been written with a white, Western, bourgeois hand.”13 His primary concern resided in changing the structures of societal oppression, which he called “institutionalized violence.”14 From this starting point, spirituality was seemingly subsumed teleologically under the mandate of effectiveness. Teology itself is formed as “a critical reflection on praxis” as a second step. Gutiérrez affirms this view- point in saying, “From the beginning, the theology of liberation posited that the first act is involvement in the liberation process, and theology came after- ward in a second act.”15 Yet, underneath the definition of praxis is an evalua- tive principle — dissolution of poverty. Gutiérrez notes, “Te criterion mentioned to judge praxis is clearly political effectiveness.”16 As a result of this foundation, the measurement of true spirituality lay within the ethos of social revolution. He says, “We are dealing with two inseparable correlations here and it is important to emphasize this. Te potential of a liberating faith, and the capacities of revolution, are intimately bound together . . . Hence it is impossible to cultivate the one without the other as well, and this is what many find unsettling.”17

Within the criterion of political effectiveness, Gutiérrez also accepted Marx- ist economic theory operationally and coupled it with a heavy reliance upon the social sciences as the proper barometers of societal change. In this, Gutiér- rez believes that Marx’s economic understanding of history is a “scientific understanding of historical reality.” He says:

right-wing to counter the people’s movement and Liberation Teology, has very little basis in the facts.” See Sepulveda, “Future Perspectives for Latin American Pentecostalism,” 190.

13

Gustavo Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, trans. Robert Barr (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1983), 200-201.

14

Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation, trans. Sister Caridad Inda and John Eagleson (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1990), xviii.

15

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 200.

16

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Notes to a Teology of Liberation,” Teological Studies 31 (1970): 250.

17

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, xx.

4

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

9

Marx deepened and renewed this line of thought in his unique way. But this required what has been called an “epistemological break” (a notion taken from Gaston Bachelard) with previous thought. Te new attitude was expressed clearly in the famous Teses on Feuerbach, in which Marx presented concisely but penetratingly the essential elements of his approach. . . . Basing his thought on these first intuitions, he went on to construct a scientific understanding of historical reality. He analyzed capi- talistic society, in which were found concrete instances of the exploitation of man by his fellows and of one social class by another. Pointing the way toward an era in history when man can live humanly, Marx created categories which allowed for the elabora- tion of a science of history.18

Te early Gutiérrez accented the Marxist aspect in his thought by noting, “Many agree with Sartre that Marxism, as the formal framework of all con- temporary philosophical thought, cannot be superseded.”19 Te accentuating of social and economic liberation led to the misguided perception that the salvation motif in Gutiérrez’s writings was almost exclusively immanistic. Gutiérrez even admitted that

[i]t may seem that we entertain precious little interest in a person’s spiritual attitudes. It could even seem that we disdain qualities of faith or of morality in the poor. We are only seeking to avoid beginning with secondary, derivative considerations in such a way that would confer them with what is primary and basic, creating an interminable number of hair splitting distinctions that in the end only yield ideas devoid of interest and historical impact.20

Given the overt political criterion for evaluating theoretical premises, anyone not involved with immediate political change was viewed axiomatically as part of the problem. Pentecostals fell readily into this category, particularly with a premillennial eschatology as the primary understanding of justice in society. However, the corresponding view from Pentecostals that Gutiérrez’s theology was nothing more than reworked Marxism made the chasm between both diametric. Both assumptions missed the mark in the stereotypical minimiza- tions about the other. Pentecostals misunderstood the theoretical foundations implicit within the ethical imperative of liberation theology, and Gutiérrez minimized the liberating effects of a theology whose historical nexus origi- nated from within the world of the poor.

18

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, xx. 19

Ibid., 59.

20

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 95.

5

10

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Te latter misunderstanding struck at the very heart of the characterizations of each position and proleptically disposed each toward a position on personal religion and, by consequence, on mysticism. Was religion a matter of the indi- vidual before God or was God exclusively in the work to liberate the oppressed? Of course, both realized, at least theoretically, that the question raised is not an either/or question but one of degree, given that humanity is made up of individuals, at least on a certain level. Leaning more to the corporate under- standing of self, Gutiérrez placed the poor and oppressed as the basis from which true spirituality began. He said,

A spiritual experience, we like to think, should be something out beyond the frontiers of human realities as profane and tainted as politics. And yet this is what we strive for here, this is our aim and goal; an encounter with the Lord, not in the poor person who is “isolated and good,” but in the oppressed person. . . . [H]istory, concrete history, is the place where God reveals the mystery of God’s personhood. God’s word comes to us in proportion to our involvement in historical becoming.21

Much of Gutierrez’s approach could easily be ascribed to the overwhelming degradation of poverty and the miniscule attention that the issue had previ- ously received in theological forums. Te problem was that most of Gutiérrez’s socioeconomic presentation gave the impression that personal faith only has value within the liberation process. Consequently, the most personal of spiri- tual evidence, conversion, was also stated in terms of self revelation in the midst of involvement with the poor. Tis, coupled with a perceived dialectical universalism, made God seem more like a Hegelian construct than a savior who was accepted personally.22 Te result was that much of the personal moti- vation for societal change was relegated to filial love as an implicit love for God. In other words, of the two Great Commandments, Gutiérrez’s presenta- tion of liberation theology emphasized the second almost as the sum total of the first and the sole extension of its meaning. Gutiérrez had aimed to link the two by showing how love for the poor was biblically equated with a love for God, which, of course, had plenty of biblical support; however, Gutiérrez’s presentation of love for the poor made love for God axiomatic in that the two were the same. Christ was in the naked, the hungry, and the imprisoned — but seemingly nowhere else. Gutiérrez notes, “And this is precisely why it [spirituality] is not a purely ‘interior,’ private attitude, but a process occurring

21

Ibid., 52.

22

Gutiérrez said, “I was greatly influenced by Hegel in his understanding of history in writing A Teology of Liberation. Personal Interview with Gutiérrez, 5 May 1994.

6

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

11

in the socio-economic, political, and cultural milieu in which we live, and which we ought to transform.”23 Terefore, there was little need to talk about spirituality prior to its implementation in praxis. Te coterminous equation made spirituality seemingly exclusive to one’s neighbor. Anything else was pietistic narcissism.

Something, or more correctly someone, was lacking. To appropriate Martin Buber, the “I” in the “I-Tou relationship” seemed to be unconditionally assumed in the philosophical category of the other presented by Gutiérrez. Te explanation given for this methodology is that theology is a critical reflec- tion on praxis from the viewpoint of the poor. Te flaw in this methodology was that the original application of this definition viewed the poor almost exclusively through a socioeconomic lens. In other words, the poor were defined by a standard that they themselves did not accept. Te poor viewed themselves as more than merely the victims of institutionalized violence. Reli- gion was not an escape from brutality and minimization; it was a full-scale rebellion to negate the denigrating terms of limitation awkwardly placed upon them by their oppressors.

A Shift in Method Is Noticed

In the early 1980s subtle shifts began to occur within Gutiérrez’s thought that revealed a change in his approach to the question of personal spirituality. Pre- viously Gutiérrez had emphasized theology as a critical reflection on praxis accomplished through the prism of sociopolitical analysis. In the early 1980s word began to leak out from Gutiérrez’s summer school sessions that Gutiérrez had begun to change, or at least modify, his approach to liberation theology. Gerhard Hanlon, who had attended the 1982 summer school session, wrote in a journal article:

In its early years liberation theology in Latin America was concerned with analyzing social reality and interpreting the Bible in terms of liberation from social and political oppression. A few years ago interest turned to the study of the popular religiosity of the masses of the oppressed and attempted to see therein values which might contribute to that liberation. Te most recent interest of Latin American theology is spirituality.24

23

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 53.

24

Gerhard Hanlon, “A Spirituality for Our Times,” Clergy Review (June 1984): 200.

7

12

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

In this article Hanlon suggests that there is a new theme in Gutiérrez’s theol- ogy. Tat theme is the “popular religiosity of the masses.” But is this a different direction for Gutiérrez’s thought? Hanlon seems to think that this is an added emphasis but not necessarily a contrary viewpoint. Others, however, find in this added emphasis a discarding of the older ways of thinking to make way for the new.

One of Gutiérrez’s harshest critics in methodology is fellow liberation theo- logian Juan Luis Segundo. In a lecture given at Regent College in 1983, Segundo made a startling remark about what he perceived as a reversal in Gutiérrez’s thinking. Segundo stated that his old friend and compatriot Gustavo Gutiérrez had abandoned the font of his former thinking. In this lecture Segundo called upon his old companion to return to the philosopher’s stone from which they were both hewn. Tat stone, said Segundo, was the sociopolitical methodology that was liberation theology’s original contribu- tion to the world. But more than this, Segundo maintained that the changes in Gutiérrez’s thought were more than just an added dimension to his thought. Segundo asserted that the changes were so drastic that it did not make sense to talk anymore about a singular continuous train of thought but rather “of at least two types of liberation theology.”25 Along these lines, Segundo sadly con- fessed, “And what is painful to me is that I no longer know whether Gustavo himself would endorse what he said then, or whether he would consider it a mere sin of his youth.”26

In 1989 Arthur McGovern, in his book Liberation Teology and Its Critics, took up some of the same questions raised by both Hanlon and Segundo and reached similar conclusions. McGovern noted, “Te revolutionary excitement has dimmed,” and as a result “Gutiérrez has devoted much of his time and writings to the question of spirituality.”27 Echoing both Hanlon and Segundo again, McGovern also noted that Gutiérrez’s liberation theology had “shifted” from a more sociopolitical agenda to one that now emphasizes more the spiri- tual side. He pointed this out by noting the differences between the two books A Teology of Liberation and We Drink from Our Own Wells. He says, “ A Teol- ogy of Liberation deals almost exclusively with the issue of sociopolitical eman-

25

Juan Luis Segundo, Signs of the Times, trans. Robert R. Barr (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1993), 67.

26

Ibid., 93.

27

Arthur McGovern, Liberation Teology and Its Critics: Toward an Assessment (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1989), 87.

8

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

13

cipation, and most of the discussion about liberation from sin deals with eliminating unjust structures caused by sin.”28 Conversely, McGovern notes,

In We Drink from Our Own Wells, Gutiérrez reflects theologically on the journey of the poor in Latin America and the journey of those who have attempted to walk with the poor. When liberation theology first emerged, Gutiérrez wrote about the “revolution- ary ferment” alive throughout Latin America. Te revolutionary excitement has dimmed, but Gutiérrez finds a deeper, more faith centered hope still strong.29

McGovern concludes, “I would clearly designate spirituality as the dominant theme of contemporary liberation theology.”30

Paul Sigmund in his book Liberation Teology at the Crossroads also sees the changes in Gutiérrez’s thought. Sigmund identifies Gutiérrez as the progenitor of what he calls the new line of theological speculation that began to depart from the older, more militant liberation theology of the early years. He says, “Many writers have seen the anticipation of the characteristic elements of lib- eration theology in the writings by Latin American theologians in the middle and early 1960s. . . . However the clearest beginnings of the new line of theo- logical speculation are in the writings of Gustavo Gutiérrez.”31 Why have all these changes occurred? Te answer, for Sigmund, is the times in which Gutiérrez wrote his books. He says,

In A Teology of Liberation, however, the emphasis is much more on the former than the latter in the sense that the structuralist anticapitalism is discussed at much greater length than the participatory populism. Tis emphasis is an understandable product of the time at which the work was written — the late 1960s and the early 1970s. As the book was being completed Chile elected a Marxist president, Salvador Allende, with the support of a coalition that also included Christians and parties of a more secular orientation. Allende’s popular unity seemed to embody the commitment to the poor and the oppressed — and to socialism — that liberation theology argued was the logical conclusion to be drawn from the scriptures.

32

28

Ibid., 82.

29

Ibid., 87.

30

Ibid., 83.

31

Paul Sigmund, Liberation Teology at the Crossroads (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 28.

32

Ibid., 39.

9

14

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Te Movement to Mysticism

Had changes occurred within the presentation of a theology of liberation? In A Teology of Liberation Gutiérrez had maintained that “theological categories are not enough. . . . we need a spirituality.”33 With the issuing of the book We Drink from Our Own Wells, Gutiérrez began to make explicit what to many of his followers was implicit, namely, that there was a verdant spirituality within the original coordinates of the theology of liberation schemata. In the fore- word to this long anticipated work, Henri Nouwen stated, “Tis book fulfills the promise that was implicit in his A Teology of Liberation.”34 In this Gutiér- rez was not abandoning his earlier emphasis but “expanding upon the view.”35 In Gutiérrez’s mind, part of the rationale for minimizing the spiritual aspects was that the tenets of spirituality for the poor should germinate from the poor as a part of their own liberation pilgrimage. He notes, “Evangelization, the proclamation of the gospel, will be genuinely liberating when the poor them- selves become its messengers.”36 Tis embryonic spirituality could not be com- plete until the poor were the artisans of their own spirituality: “Te spirituality of liberation will have its point of departure in the spirituality of the anawin.”37 As Gutiérrez warmly anticipated this new type of spirituality, he felt con- strained to contain his own ruminations since the people of liberation would traverse unknown ground in the birthing of a spiritual paradigm. He notes,

Te problem, however, is not only to find a new theological framework. Te personal and community prayer of many Christians committed to the process of liberation is undergoing a serious crisis. Tis could purify prayer life of childish attitudes, routine, and escapes. But it will not do this if new paths are not broken and new spiritual experiences are not lived. . . . Tere is a great need for a spirituality of liberation; yet in Latin America those who have opted to participate in the process of liberation as we have outlined it above, comprise, in a manner of speaking, a first Christian generation. In many areas of their life they are without a theological and spiritual tradition. Tey are creating their own.38

33

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, 117.

34

Henri Nouwen’s foreword in Gustavo Gutiérrez, We Drink from Our Own Wells: Te Spiri- tual Journey of a People (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1984), xiii.

35

Tis is the title Gutiérrez gave to his new introduction in commemoration of the fifteenth anniversary edition of A Teology of Liberation, xviii.

36

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 22.

37

Ibid., 53.

38

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, 74.

10

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

15

At least in emphasis, Gutiérrez’s liberation spirituality had begun to change. Te question was what would the new changes look like and how would the new emphasis on spirituality cohere with the old expressions of liberation?

A funny thing occurred in the forging of new spiritualities for the theology of liberation. Te new formulations of faith began to look suspiciously like older, more traditional spiritualities within Roman Catholic mystical life. Sigmund commented, “Without admitting that he was doing so, Gutiérrez continued to modify his approach and to emphasize the agreement between his version of liberation theology and the social teaching of the church.”39 Was it a coincidence that the spiritual evolution looked particularly Roman Catho- lic? True, Gutiérrez had previously noted that “without ‘contemplative life,’ to use a traditional term, there is no authentic Christian life.”40 But in its embry- onic development, he had maintained, “what this contemplative life will be is still unknown.”41 Te unknown of the earlier works became known in such traditional Catholic mystics as St. John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila. Monastic pillars of contemplation also began to filter into the thought of Gutiérrez in Augustine and particularly in Ignatius Loyola (contemplation in action). Here, Gutiérrez began to find historical compatriots of liberation who had traversed the spiritual and had never given up the concern for action. As a result, the interior life was seen not as an impediment to liberation but rather as an ally. A recent work by Gutiérrez emphatically embraces spiritual- ity’s help in observing that “spirituality provides strength and durability for social options.”42 In Gutiérrez’s rereading of the mystical and monastic pil- grims, a new vantage point was found to embrace the historical expressions of the faith without losing the present praxis. Te mystical had been demytholo- gized of self-absorbed pietism and had become practical. As a result, Gutiérrez began to mine the deeper recesses of mysticism laden within Christian history. Now Gutiérrez would even become an apostle for the mystical life: “Only within the framework provided by mysticism and practice,” he observed, “is it possible to develop a meaningful discourse about God that is both authentic and respectful of its object.”43 Specifically, the call to contemplation within

39

Sigmund, Liberation Teology at the Crossroads, 171.

40

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, 74.

41

Ibid.

42

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Te Teology of Liberation: Perspectives and Tasks,” trans. Fernando F. Segonia, in Toward a New Heaven and a New Earth: Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2003), 297.

43

Gustavo Gutiérrez, Te Truth Shall Make You Free (Maryknoll, NY Orbis Books, 1990), 55.

11

16

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

mysticism was now seen as an active participation in the process of liberation as opposed to a fearful withdrawal from the world of need.

Contemplation

What was it about mysticism that attracted the later Gutiérrez? Te answer, of course, is praxis. Gutiérrez had always held to a concept of spirituality that included contemplation, but the adoption of mysticism thrust Gutiérrez into the interior life, which previously had only occupied a footnote in his think- ing. Gutiérrez noted, “Poverty was always a central point in the history of spirituality, and it was always linked to the contemplative life.”44 In Gutiérrez’s life as a parish priest he would often reflect upon the contemplative aspect of the poor, both in merely being within the repose of the church and in active praying. Gutiérrez noted the poor’s abiding presence in the local churches as something more than a place to get out of the rain. He says, “Te poor spend long hours reflecting on their lives [in the church].”45 Reflexively and naturally the poor move from their reflection to prayer. He says, “Tere is perhaps noth- ing more impressive and creative than the praying praxis of Christians among the poor and oppressed. Teirs is not a prayer divorced from the liberating praxis of people. On the contrary, the Christian prayer of the poor springs up from roots in that very praxis.”46

Prayer

Prayer in the spirituality of liberation is not to be thought of as routine, pas- sive, or accepting of degradation. Nor does contemplative silence before God equate to an acceptance of brutality. Gutiérrez states, “Passivity or quietism not only is not a real acknowledgement of the gratuitous love of God, but even denies it or deforms it.”47 Prayer, then, actually questions God about the unac- ceptability of suffering from within the constructs of God’s loving nature: “Teology addresses how to speak about God from the sufferings of the inno-

44

James L. Heff, ed., Believing Scholars: Ten Catholic Intellectuals (New York: Fordham Uni- versity Press, 2005), 45.

45

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Liberation Teology for the Twenty-First Century” in Romero’s Legacy: Te Call to Peace and Justice, ed. Pillar Closkey (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007), 55.

46

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 107.

47

Gutiérrez, Te Truth Shall Make You Free, 35.

12

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

17

cents, the suffering of the poor.”48 Gutiérrez likewise maintains, “If the ele- ment of injustice be added to this situation of suffering, it can produce resentment and a rejection of the presence and existence of God, because God’s love becomes difficult to understand for one living a life of unmerited affliction.”49 It also maintains the theological structure of struggle before God (coram Deo) as opposed to in atheistic disengagement. Gutiérrez affirms, “Tis painful dialectical approach to God is one of the most profound messages of the book of Job.”50 Te prelude of prayer is central to all God talk because it begins in an attitude of faith from which all talk of God must originate.

True prayer also moves one to action. To pray without a commitment to action nullifies the prayers uttered as faithless. In this dialectical process the surd of suffering moves one to a mystical appropriation of Christ’s suffering. In all unjust suffering the Christian is called to understand that Christ suffers with the victim and “will be in agony until the end of the world.”51 In this suf- fering faith is born — not in a dismissing manner but rather in a mystical paschal participation. From identification with Christ a “hermeneutic of hope” is appropriated that sees in the resurrection of Christ the future redemption.52 Yet, because the suffering is not abated in the present time, there is a need for continued contemplation. Tis discipline of silent meditation beckons the sufferer into an interior life that helps them persevere through the present affliction. Gutiérrez notes, “Teology will then be speech that has been enriched by silence.”53 Yet, the present disciplines and the future hope do not always provide easy answers to the larger, more personal questions of theodicy. In this Gutiérrez confesses, “Tis question is larger than our capacity to answer it. It is a very deep, personal question. Ultimately, we have no answers except to be with the poor.”54 As a result, contemplation continues and compassion follows from the inability (both personal and corporate) to explain God’s love in the midst of evil. Perhaps this is why Gutiérrez was fond of quoting Jose Maria Arguedas’ aphorism, “What we know is much less than the great hope we feel.”55

48

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “How Do You Tell the Poor God Loves You?” Interview by Mev Puleo, St. Anthony Messenger 96 (February 1989): 10.

49

Gustavo Gutiérrez, On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, trans. Matthew J. O’Connell (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1987), 13.

50

Ibid., 65.

51

Ibid., 101.

52

Gutiérrez, Te Power of the Poor in History, 15.

53

Ibid., xiv.

54

Ibid.

55

Ibid., 22.

13

18

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

Revelation and Praxis

As part of the liberation imperative, Gutiérrez also advocates the age-old dis- cipline of the reading of the Scriptures. From the beginning of Gutiérrez’s project of liberation, the Bible has held a central position. However, even the Scriptures seem to take on a new dimension within the thought of the latter Gutiérrez. Te early Gutiérrez’s epistemology located truth as a dialectical interaction with praxis. He says, “For what we are concerned with is a re- reading of the gospel message within the praxis of liberation.”56 In this he agrees with Congar in saying, “It [the church] must open as it were a new chapter of the theological-pastoral epistemology. Instead of using only revela- tion and tradition as starting points, as classical theology has generally done, it must start with the facts and questions derived from the world and from history.”57 He also notes that “all truth must modify the real world . . . knowl- edge is thus dialectical starts and returns.”58 By 1983 he had revised his episte- mology to include a more preeminent status for revelation in epistemology. He said, “Te ultimate criterion for judgment comes from revelation not from praxis itself.”59 Correspondingly, Gutiérrez also began to modify his position on the social sciences’ place in epistemology. He wrote, “Te Bible concept is very rich, richer than a purely sociological understanding of the poor.”60

Has Gutiérrez’s Mysticism Created an Open Door for Dialogue?

Is Gutiérrez’s incorporation of mysticism a theological portal through which dialogue with Pentecostalism might commence? Given the chasm that has historically separated them, the answer to such a question is at best tentative. First, while the accentuation of mysticism is without question an elaboration of Gutiérrez’s latent spirituality, the translation from mysticism to Pentecostal- ism is not a seamless transition from either side. Yet, there are voices within Pentecostalism who believe that the chasm is not too deep and that a latent commonality abides between the two. Miroslav Volf is one who implores these two theologies to come together. He states, “It is of ecumenical importance for

56

Ibid., 66.

57

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, 9.

58

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Te Praxis of Liberation and the Christian Faith,” Humane Vitae (September 1974): 373.

59

Gustavo Gutiérrez, Te Truth Shall Make You Free, 101.

60

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Gutiérrez Reflects on 15 Years of Liberation Teology,” Interview by Latinamerica Press, Latinamerica Press 15 (19 May 1983): 5-7.

14

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

19

liberation theology and Pentecostal theology to recognize each other as feud- ing family members,” as opposed to enemies.61 Te reason for this, Volf points out, is an increasing awareness within the Pentecostal movement of both the liberation imperative and the conscientization of socioeconomic need. At first glance, he says, “Liberation theology and Pentecostal theology seem to be prime examples of radically opposing theologies.”62 As Volf notes, however, the two theologies have much more in common than either one of them may wish to believe: “Individual groups of Pentecostalists around the world seem to be slowly discovering the socioeconomic implications of their soteriology, and liberation theologians are becoming more aware of the need for a spiritual framework for their socioeconomic activity.”63 Dario Lopez Rodriguez com- ments on the liberating activity: “Today there is sufficient evidence from sev- eral countries of Latin America that a gradual awakening of the social conscience of a significant sector of the Pentecostal movement is taking place.”64 Doug Peterson agrees: “Ultimately, by empowering people who were previ- ously denied a voice, the Pentecostal Movement in Latin America has acquired a revolutionary potential.”65

On the question of spirituality, Simon Chan also sees a great deal of conti- nuity between Catholic mysticism and Pentecostalism. Within the two tradi- tions Chan sees great possibility in the celebration of the Eucharist as a “central” Pentecostal event.66 Chan also views tongues as, in essence, an expres- sion of Teresa of Avilla’s progression to joy “in which joy becomes so over- whelming that the soul could only respond with all tongues and heavenly madness.”67 Chan says, “Pentecostalism cannot be regarded as a marginal movement, much less an aberration: it is a spiritual movement that matches in every way the time-tested development in Catholic tradition.”68 Chan even believes that the Pentecostal giftings work best in the structure of Roman Catholic and the Episcopal Charismatic traditions. He notes, “In fact I would

61

Miroslav Volf, “Materiality of Salvation: An Investigation in the Soteriologies of Liberation and Pentecostal Teologies,” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 26, no. 3 (Summer 1989): 449.

62

Ibid., 447.

63

Ibid., 460.

64

Dario Lopez Rodriguez, “A Critical Review of Douglas Peterson’s Not by Might Nor by Power: A Pentecostal Teology of Social Concern in Latin America,” Journal of Pentecostal Teology 17 (2000): 136.

65

Douglas Peterson, “Latin American Pentecostalism: Social Capital, Networks, and Poli- tics,” Pneuma: Te Journal of Pentecostal Theology 26, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 306.

66

Chan, “Pentecostal Teology and Christian Spiritual Tradition,” 108.

67

Ibid., 60.

68

Ibid., 71.

15

20

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

like to show that [the Pentecostal reality] is better traditioned in a church that recognizes the constitutive role of the sacraments and the Spirit.”69 But is there a tradition within liberation theology that militates against the indigenous nature of Pentecostalism?

Ecclesiology

In “La Koinonia Eclesial” Gutiérrez proclaims that “the task of the church is as an extension of the missions of the Son and the Spirit.”70 Even in Gutiérrez’s earlier thought he had stated that “spirituality in the strict and profound sense of the word is the dominion of the Spirit.”71 But what does this mean in rela- tion to the ecclesiology? In the formation of the spirituality of liberation, Gutiérrez earlier maintained that he was hesitant to conjecture as to the expli- cation of this “new” spirituality. His reasoning was that the people of libera- tion were “first generation” liberationists; therefore, what liberation spirituality comprised was subsequently in an embryonic and much too formative stage. Gutiérrez has consistently maintained that the poor will not be truly liberated until they are the artisans of their own spirituality. But, as Segundo pointed out, “Something was obvious . . . the common people had neither understood nor welcomed anything from the first theology of liberation, and had actually reacted against its criticism of the supposed oppressive elements of popular religions.”72 Paradoxically, many now have begun to criticize liberation theol- ogy for its lack of indigenous authenticity and for being primarily an academic exercise. Solivan says, “Te power and authenticity present in the early voices of the liberation theologians have been diluted by the process of academic advancement.”73 Charles Self has asserted that “Pentecostalism is truly a faith of the poor and is thus distinct from some liberation theology movements which are for the poor.”74 Tis critique echoes Moltmann’s previous criticism that the theology of liberation had more to do with European theology than it

69

Ibid., 15.

70

Gustavo Gutiérrez, “La Koinonia Eclesial,” trans. David Bustos, Paginas 200 (August 2006): 22.

71

Gutiérrez, A Teology of Liberation, 117.

72

Segundo, Signs of the Times, 74.

73

Samuel Solivan, “Te Spirit, Pathos, and Liberation: Toward an Hispanic Pentecostal Te- ology,” Journal of Pentecostal Supplement Series 14 (1998): 36.

74

Charles Self, “Conscientization, Conversion, and Convergence: Reflections on Base Com- munities and Emerging Pentecostalism in Latin America,” Pneuma: Te Journal of the Society of Pentecostal Theology 14, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 63.

16

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

21

did with any indigenous ecclesiology. In his “Open Letter to Jose Miguez Bonino,” Moltmann remarked that Gutiérrez’s work “offers many new insights — but precisely only in the framework of Europe’s history, scarcely any in the history of Latin America.”75 Gutiérrez often acknowledges his Euro- pean pedagogy as an encumbrance to his own veracity in speaking for the poor. Solivan states, “Without the poor — those who suffer — as subject, theology denigrates into the academic exercise of cognitive praxis.”76 For a privileged theologian educated in first-rate schools, it would be hard to sepa- rate the wineskins of austere academia from the degradation of poverty. To be sure, Gutiérrez has advocated and modeled the incarnational lifestyle, but does this model extend to his theological method? Or theoretically rephrased, does praxis, itself, have a criterion that uncritically incorporates a residual European pedagogy?

Pneumatology

In We Drink from Our Own Wells, Gutiérrez created considerable distance between “popular religion” and liberation theology by juxtaposing those who believe in miracles with those who are involved in the work of liberation: “Te power of the Spirit leads to love of God and others and not to the working of miracles.”77 Here there is a clear divergence from the view of the poor as it relates to both love and pneumatology. Exceedingly little is said throughout Gutiérrez’s works about pneumatology.78 It is an area of immense neglect. As a result, a penetrating criticism must be directed at this lack, and a question of sufficiency must be raised when the most theologically active participant in historical change (the Holy Spirit) is absent. But perhaps this is the point. Does the weakness in Gutiérrez’s pneumatology nuance his entire understand- ing of the Pentecostal movement? And does this lack predispose the theology of liberation to a critique of immanence from which the Pentecostal poor can speak more adequately? Solivan again points out that the two, miracles and

75

Jürgen Moltmann, “An Open Letter to Jose Miguez Bonino,” Christianity in Crisis 36 (29 March 1976): 5.

76

Solivan, “Te Spirit, Pathos, and Liberation,” 65.

77

Gutiérrez, We Drink from Our Own Wells, 63.

78

A quick perusal of the indexes of Gutiérrez’s books reveals the disparity. In Te Truth Shall Make You Free, the index does not have any references to the Holy Spirit. Tere are thirty-seven to Jesus and eleven to Marx. In A Teology of Liberation there are 107 references to Jesus, ten to Marx, and three to the Holy Spirit. All of the books that Gutiérrez has written display this disparity.

17

22

J. Davis / Pneuma 33 (2011) 5-24

liberation imperatives, are not inimical to one another: “For many suffering people what makes God’s promise possible in their present experience is the acceptance of the miraculous. . . .Te experiences of promises fulfilled today serve as first fruits of what is yet in store.”79 Gutiérrez emphasizes only the silent suffering aspect of transcendence. But why is it inconsistent to believe, as the poor do, that God’s identification with weakness is equally as true as the Holy Spirit’s manifestation of power? On an economic level Gutiérrez agrees — it is just in the supernatural aspects where there is resistance. Of course, one might ask how God acting supernaturally now would be any dif- ferent from the Word becoming flesh and dwelling among us long ago. But the fallout does not end there. Systemically there is another more problematic result, namely, liberation itself.

Eschatology