Pentecostal Theology of Freedom for the Postcommunist Era

“Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith

Christ hath made us free” for “if the Son therefore

shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed”

This paper is intended as a part of larger research entitled Theology of the Persecuted Church. It focuses on they way freedom is understood by the underground church and its successor, the postcommunist church after the fall of the Communist regime. In this sense, the research presents the theological view of freedom from the time of postmodern transition in Eastern Europe in retrospect with the times of underground worship and in dialogue with the major modern theologians. The main purpose is to construct an authentic view of freedom in the major areas of the life and ministry of the postcommunist Pentecostal church.

Postcommunist Europe

On his first official visit to West Germany in May 1989, Mikhail Gorbachev informed Chancellor Kohl that the Brezhnev doctrine had been abandoned and Moscow was no longer willing to use force to prevent democratic transformation of its satellite states. At 6:53 p.m. on November 9, 1989, a member of the new East German government gave a press conference to inform that the new East German travel law would be implemented immediately. At the East Berlin Bornholmer Strasse, the people demanded to open the border. At 10:30 p.m. the border was opened.[1] That meant the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War.

The unification of one Germany brought the clash of two political extremes within one nation. It brought together two Europes kept apart for half-a-century, a dynamic which introduced the continent to a new set of opportunities among which was the vision for a unified Europe and its realization.

A new set of dilemmas was introduced as well. Among all economical, political, social, cultural and simply human points of diversity, religion remained central for the process through which the European Union was emerging. The official “United in Diversity” (reminding of the American E Pluribus Unum) claimed unification, without mentioning God. The new European constitution announced that Europe draws “inspiration from the cultural, religious and humanist inheritance of Europe.”[2]

For us who lived in the last days of Communist Bulgarian, the fall of the wall was a miracle which the world witnessed. Coming out from the severe Communist persecution and surrounded by the Balkan religious wars, suddenly the country of Bulgaria experienced a time of liberation which gave the start of spiritual revival mobilizing Bulgarian Protestants. In the midst of extreme poverty, due to prolonged economical crisis, this revival became an answer for many. It also provided a sense of liberation, but not in the Western political understanding of democracy and freedom, but rather liberation toward the realization of the Kingdom, a world much higher, much better and in way more realistic than any human ideality. The liberation from sin then turns not only into a social movement, but as a theological conception it provides an alternative to the existing culture thus becoming a reaction against the surrounding context and proposing a new theological model and a new paradigm for life itself based on substantive faith and belief.

Freedom of Will

Even when approached theologically, in the Eastern European postcommunist context today, the term freedom of will carries a strong political nuance. For many Eastern European Protestants, freedom characterizes the struggle against the communism regime and the divine motivation to endure it as a calling of faith for the individual and the community.

The years before communist era were characterized with opposition against the historical monopoly of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In this context, the protestant movement in Bulgaria also struggled against spiritual dominion defending the cause of religious freedom and the right of each individual and community to believe and express beliefs.

The hundred years of Bulgarian Protestantism have been accompanied with constant struggle against oppression of conscience and will thus creating a general acceptance of free human will. This has coincided with the theology of the largest and fastest growing Evangelical movements in Bulgaria. In this context, even evangelical churches, like the Baptists, have grown to accept and practice the doctrine of free will.

Based on the political, socioeconomic and purely ecclesial factors, in postcommunist Eastern Europe, the Calvinistic paradigm of predestination and election as practiced in a Western sense are not successful. This is based partially on their new doctrinal presence within the Bulgarian reality and their untested effectiveness through under persecution. It is also natural that they are often qualified in parallel with political and religious oppression, and therefore rejected as divine attributes or actions. If human regimes are oppressive through limiting freedom and consciences, how is God to identify with such regimes and practice the same type of “horrible decree?” On the contrary, in Eastern European Protestant theology, God is seen as a Liberator of human consciences and a desire for freedom.

By no means, is this tension to be confused with a denial of the total authority of God. God remains the electing God in Jesus Christ, but how?[3] Is it through a “horrible decree” or through a personal life-changing experience defined by the Bible? Is it through an oppressive act of lawful but unconditional predetermination which God by His nature is omnipotent to implement, or through an act of supernatural transformation of humanity through divine self-sacrifice? And does this election barricade every possible human choice? No, as it is obvious in the denial of Peter; but also as seen in his restoration, that every choice of human will is answered by God through unconditional divine love.

Therefore, we experience “the secret of predestination to blessedness,” not in a cause and effect paradigm as Augustine and the Reformers, but rather through preserving its significance by experiencing the love of God.[4] Thus, the human will is freed by the love of God to receive salvation for eternity. The human freedom then is not ignored or oppressed, but on the contrary it is “placed in the context of cosmic drama” where the real bondage is not the one by God, but the one by sin which oppresses the human will and distances it to death. The Gospel, however, proclaims the victory of Christ over these oppressors thus liberating human will to its initial creation state as a gift from God.[5] This theology comes from a concrete experience of God in real life, and the quest to serve and follow God. As theology shows that the truth about God and the truth about ourselves always go together, the experience of God is a constant tension and a dynamic process, rather than blind servanthood to rigid principles that can never fully encompass the divine will. And through this experience of liberation of the human will in order that one may be free to choose salvation through Christ, God establishes His “testament of freedom.”[6]

Freedom from Oppression

As God liberates humanity from sin, He liberates it from sin’s moral and social consequences. Thus, forgiveness of sin presupposes not only the quest for sanctification and perfection after the image of God, but also the struggle against oppression and establishment of social balance. As the above shows, the postcommunist revival in Eastern Europe cannot be explored apart from the contextual political and socioeconomic dynamics. The reason for this is that the Spirit with value before God is a social spirit that makes the expression of the divine liberation the very purpose of the existence of the church.[7] The practice of this expression challenges the relationship between theology and practice as it questions theology’s epistemological and praxis relationship to the oppressed with whom Christ is crucified.[8]

As in such context, theology is challenged to identify with action, the church must choose between contextualizing and enforcing theology. To choose contextualization is to attempt to relate it to the existing culture thus creating a state of relativism. Such approach is observed in some Asian and Black theology. The danger is to go beyond the boundary pass which theology ceases being theology in action and becomes simply a nominal religious culture. In Eastern Europe, such approach has been long-practiced by the Eastern Orthodox and has unquestionably resulted in nominal religion. The nominality of its expression has been a factor preventing the experience of God, thus denouncing the very reason for the church’s existence. Attempts to restore the Eastern Orthodox “symphony” between church and state have altered the existence of the independent synods which claim the succession of the same historical religious institution.

The second direction, to move toward enforcement of theology after the paradigm proposed by Liberation theology, is quiet a dangerous approach often resulting in armed conflicts. Keeping in mind the historical tension on the Balkans and Bulgaria’s success in undergoing the postcommunist transition without an armed civil conflict, this approach is virtually inapplicable. Therefore, an alternative must be proposed before history itself become oppression.

In this context, a move toward a theology of freedom seems most reasonable. It must purpose to prevent political and socioeconomic oppressions which are already present in various legal and illegal forms in Bulgaria. Such paradigm must also be concerned with intrachurch oppressive tensions which are present both among and within religious denominations, striving especially against such oppressive modes that come from the desire of an oppressed mentality to oppress others.

Such working model of social transformation is presented in Paul’s Epistle to Philemon. An older interpretation of the book explains that Onesimus, a runaway slave, meets Paul in prison, becomes a Christian and is sent by Paul back to his master. A more cotemporary interpretation claims that Onesimus is a slave sent by Philemon to help care for Paul in prison where he converts to Christianity and desires to stay with Paul as a missionary associate.

Regardless of the interpretation of the story plot, the epistle carefully presents a more in-depth set of problems that deal with persecution, imperialism, slavery, mastership, classes, ownership, imprisonment and above all justice. It further makes a more aggressive mood and places the church, represented in the text not merely by masses, but by the very divine appointment of apostolic authority.

The theme of imprisonment as a direct result of persecution is clearly present through the epistle’s plot and more specifically verses 1, 9, 13 where Paul uses the expression “prisoner of Christ” to describe his present status. The expression “prisoner of Christ” carries a sense of belongingness making the phrase different than the sometimes rendered “prisoner for Christ.” While the latter wrong rendering moves the focus toward the purpose of Paul’s imprisonment, the Greek genitive in the phrase “prisoner of Christ” denotes ownership. Although imprisoned in a Roman prison and kept by a Roman guard, Paul denies the Roman Empire ownership of himself, thus claming that he is owned by Christ alone. This is also a denial of the Roman citizenship that has led to this oppressive state of persecution and the recognition of a citizenship in the divine reality of liberation.

Paul’s negation goes a step further, proposing that while the Roman Empire may be authoritative in the temporal context, by no means it is authoritative in the spiritual eternal reality. Having established the temporality of Rome and the eternity of God, Paul denies to the Roman Empire the right to pronounce judgment over social injustice and to establish social status or world order, proposing that no one but the Christian church is the agent divinely designed and supernaturally equipped for these functions. The social injustice of persecution and wrongful imprisonment, the social tensions between classes, the problems within the church and every dilemma presented in the epistle are to be judged by no one but God through his elect. The reality of the situation is that the church is experiencing severe persecuting because the Roman Empire is denying the church social space. Paul, however, denies the reality of such oppressive human system and claims that the church is the one that must deny social space for oppressive structures as the Roman Empire.

The text calls for revolution; not merely, a revolution in the physical violent sense, but a revolution of the mind where human existence and mentality are liberated through Biblical paradigm combined with divine supernatural power to participate in a new spiritual social reality where justice is set by the standard of God. Such a move calls for a new paradigm and for a theology of freedom which creates an anti-culture and an alternative culture to the existing oppressive system. Such idea challenges the church with the claim that Christianity is and should be a scandal and an offence to the world, and not merely a religion but the belief that “Jesus is the most hazardous of all hazards.”[9]

Feast of Freedom or the Bulgarian Easter

Amidst political and socioeconomic crises since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Bulgaria has experienced a rebirth of Bulgarian spirituality. Many observers have referred to this restoration process as the rebirth of the Bulgarian Easter, and even which historically has been connected with the unity and power of the Bulgarian nation.

Bulgaria accepted a Christian country in 864 AD under the reign of Kniaz Boris I. A millennium later, in the middle of the 19th century, Bulgaria found itself occupied by the Ottoman Empire and religiously restricted by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchy which dictated the religious expression of the Bulgarian church.

On April 3, 1860, during Easter Sunday service in Constantinople, the Bulgarian bishop Illarion of Makriopol expressed the will of the Bulgarian people by solemnly proclaiming the separation of the Bulgarian church from the patriarchal in Constantinople. The day commemorating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ coincided with the resuscitation of the Bulgarian people. Although, the struggle continued for another decade, under the influence of Russia, Turkey was forced to legally recognize the independence of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. In 1870 a firman of the sultan decreed the establishment of an autonomous Bulgarian church institution.

The connection between the historical Bulgarian Easter and the contemporary rebirth of Bulgarian spirituality has been used in many aspects of the Bulgarian politics and culture at the beginning of the 21st century. As part of the Eastern Church, Bulgarian orthodox theology pays much more attention to the resurrection rather than to the birth of Christ thus placing its eschatological hope in a future experience rather then a past one. Such dynamic is natural, as the acceptance of Christianity in Bulgaria purposes to bring hope in national politics and communal life. Thus, in an almost historical tradition, the Bulgarian Easter represents the Bulgarian eschatological hope for a supernatural national revival. It also communicates with the sense of liberation from political, economical and religious oppression and a longing for the freedom to live life.

The Bulgarian Easter then provides an alternative to the present moment of tension and straggle in the crucifixion. Similar to Moltmann’s view of the resurrection of Christ, the Bulgarian hope foresees the resurrection of the Bulgarian nation as a divine act of protest against oppression and injustice and as recognition of God’s passion for life.[10] Thus, the resurrection is an alternative not only to the present world, but also to the reality of eternal death.

Death is therefore seen not only as an agent of eternity, but also as an agent of fear, suffering and oppression in the present reality which affects life in all its economical, political, social and even religious aspects. As death diminishes the value of life, the liberating power from Easter often remains ignored. But in order for the church to continue being a church, it must speak as a witness of the resurrection which is impossible without participating in God’s divine liberation which recreates the word to its original state of creation. Thus, the hope of Easter means rebirth of the living hope.

The resurrection hope is an influential factor which directs the life dynamics of the church beyond its walls. Being liberated from sin, the believer desires the liberation of others and claims the right to serve. But true Biblical servanthood cannot exist and therefore does not tolerate oppression, thus becoming a social transformation factor in the midst of oppressive cultures. The resurrected church rebels against the destruction of life and the denial of the right of very human to live. But different than other human systems, the church does not feed off its resistance against oppression. Its source of power is the eschatological hope for the full restoration of life and its eternal continuation in eternity.

A final question must be raised about the pessimistic character of such hope, as traditional evangelical eschatology in Bulgaria has been premillennial and due to its Pentecostal majority clearly pretribulation. Such eschatological views, at large, have been considered to be pessimistic and escapist in nature due to their strong focus on the future. Yet, such determinative presupposition seems inaccurate and much limited in its observation when applied within the postcommunist context where Protestant churches have been greatly involved in the struggle against oppressive regimes and constraining politics even to the point of martyrdom.

It is then natural, that in the underground context of persecution it is unthinkable for the church to identify with the regime in anyway. Actually, such identification is vied by the believers as spiritual treason and cooperation with authority is viewed as backsliding. By no means, however, is such a premillennial eschatological view in this context pessimistic for the church. Neither does the church remain unconcerned with the present reality. On the contrary, through its very act of negation of the right of an oppressive system to dictate reality, the church establishes an alternative culture which is the Kingdom of God. Thus in the midst of persecution and oppression, the church remains in its Biblical boundaries as an agent of the Kingdom of God by providing eschatological hope.

Yes, this eschatological view is escapist, as it promotes eternal separation from the oppressive reality. What other alternative can a persecuted and underground church find to survive and relate to the Biblical image of the ecclesia and at the same time it is clearly concerned with the transformation of the present world as shown above? For while its pessimism concerns the oppressive system of the world, its optimism declares the church as an already-reality in which freedom of sin, death and oppression and eternity with God is celebrated. Therefore, the church itself remains an optimistic reality and optimistic eschatological hope. For, without this hope the tension of life toward future and even life it self will vanish.[11] Without hope for the beyond, we remain in the now for eternity.

Epilogue

Due to its relational and reactional role to historical process, Eastern European postcommunist theology is a new historical and theological event. Yet, as theology of freedom, it relates to other theological approaches internationally. This similarity is enforced by the approaching postmodern era which the Bulgarian nation seems unprepared to understand. In such context, the church and its theology become the agents providing answers to social tensions.

Postcommunist theology provides a point of departure from the oppressive system of the communist regime toward a new social and ecclesial alternative. Such dynamic is by no means new to the Protestant movement in Bulgaria, which has dealt successfully with these same issues even in more severe context of underground existence and persecution. Therefore, the church has proved its commitment to identify with the oppressed through addressing and engaging its experience through the experience of God and its adequate and substantive theological interpretation. Such approach provides an alternative to oppressive system and structures, unquestionably critiques their tools and methods, and rebukes the agents who represent and practice them, thus denying them place in history.

A further concern for developing strategies for social transformation is also strongly present including education, law, politics and economics. These dynamics employ Christians in a common task and motivate the church for further development and implementation in order to connect theology with practice and thus to fulfill the divine calling for church’s role in the processes of restoration of justice and social transformation, both now and eschatologically.

Bibliography

Anderson, David E. “European Union Debate on Religion in Constitution Continues”

May 26, 2004.

Barth, Karl (tr. E.C. Hoskyns), The Epistle to the Romans (Oxford: Oxford University

Press: n/a).

Ford, David F. ed., The Modern Theologians (Malden: Blackwell Publishers, 1997).

Geffrey B. Kelly & F. Burton Nelson, A Testament to Freedom: The Essential Writings

of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (San Francisco: Harper Publishing House, 1995).

Green, Clifford. Karl Barth: Theologian of Freedom (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989).

Grentz, Stanley J. Theology for the Community of God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans

Publishing Company, 1994).

Johnson, Ed. Associated Press, June 19, 2004.

Moltmann, Jürgen. The Power of the Powerless, (Norwich: SCM Press Ltd., 1983).

Taylor, Mark K. Paul Tillich: Theologian of the Boundaries (London: Collins, 1987).

[1] The Fall of the Berlin Wall, http://www.dailysoft.com/berlinwall/history/fall-of-berlinwall.htm June 29, 2004; also Jeremy Isaacs and Taylor Downing, The Cold War, Thomas Fleming, The Berlin Wall and Wolfgang Schneider, Leipziger Demotagebuch.

[2] Ed Johnson, Associated Press, June 19, 2004 and David E. Anderson, “European Union Debate on Religion in Constitution Continues” May 26, 2004.

[3] Clifford Green, Karl Barth: Theologian of Freedom (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 184.

[4] Karl Barth, (tr. E.C. Hoskyns), The Epistle to the Romans (Oxford: Oxford University Press: n/a), 324.

[5] Stanley J. Grentz, Theology for the Community of God (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994), 437.

[6] Geffrey B. Kelly & F. Burton Nelson, A Testament to Freedom: The Essential Writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (San Francisco: Harper Publishing House, 1995).

[7] Green, 106.

[8] David F. Ford, ed., The Modern Theologians (Malden: Blackwell Publishers, 1997), 369.

[9] Barth, 99.

[10] Jürgen Moltmann, The Power of the Powerless, (Norwich: SCM Press Ltd., 1983).

[11] Mark K. Taylor, Paul Tillich: Theologian of the Boundaries (London: Collins, 1987), 325.

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith

The modern call for Primitivism derives from the idea of personal experience with God. There is yet no truth for and about Pentecostalism that does not emerge from experience. Irrational in thinking and in an intimate parallel to the story of the Primitive Church, Pentecostalism combines the discomfort and weakness of the oppressed and persecuted. It is the story of one and yet many that excels through the piety of the search for holiness and the power of the supernatural experience of Pentecost. It is the call for the reclaiming and restoration of “the faith once delivered to the saints.”

Such an idea of “looking back to the church of antiquity” derives from a Puritan background and is indisputably Wesleyan. In a letter to the Vicar of Shoreham in Kent, Wesley writes that the parallel between the present reality and the past tradition must remain close. For Wesley, the primitive church was the church of the first three centuries. Equality in the community as in the primitive church was the context in which Wesley ministered. Everyone was allowed to preach, both deacons and evangelists, and even women “when under extraordinary inspiration”

Of course, for Wesley, the Primitive Church was restored with the Church of England. The Pentecostal response was quite different, “The Methodists say that John Wesley set the standard. We go beyond Wesley; we go back to Christ and the apostles, to the days of pure primitive Christianity, to the inspired Word of truth.” The main characteristic of restoration was the personal experience of God. This experience was vividly presented by the Wesleyan interpreters in the quadrilateral along with reason, tradition and scripture. Such a scheme, however, may not be fully sufficient to describe the Pentecostal identity, as well as the paradigm of the Primitive Church.

The experience of God in a Pentecostal context carries a more holistic role, which is connected with the expression of the individual’s story and identity in both personal and corporate ecclesial settings. Through the experience then, they become a collaboration of the story of the many, and at the same time remain in the boundaries of their personal identity. The experience of both the individual and the community that holistically and circularly surrounds Pentecostalism is expressed in prayer, power and praxis.

Since Pentecostalism is based on the personal experience of God, prayer as the means of spiritual communication is its beginning. Being the source of spiritual power in the individual’s life it becomes the means of existence within the community of believers. Power derives only from God through a spiritual relationship which expressed through prayer, develops as a factor of constant change. The product is a unique praxis, which in the quest for church holiness and personal morality appeals for redefinition of the original ecclesial purpose and identification with the lives of the first Christians. The triangular formula of prayer, power and praxis is then the basis for Pentecostal theology.

Pentecostals claim primitivism aplenty, conformity to the apostolic experience of Pentecost and the Book of Acts. It affirms that modern Christianity can rediscover and re-appropriate the power of the Holy Spirit, described in the New Testament and particularly in Acts of the Apostles. In a social context, it was a call against public injustice. Globally the Pentecostal movement was a powerful revival that appeared almost simultaneously in various parts of the world in the beginning of the twentieth century. In the United States it occurred during the time of spiritual search.

During the first seventy years of national life of the USA barely 1.6 million immigrants arrived. In 1861-1900 fourteen million entered the country, and it was precisely within the recorded decade of 1901-10, with 8.8 million immigrants, that the Pentecostal movement began. The mass migration was in an immediate connection with the rapid urbanization and industrialization occurring in a chronological parallel. Since first generation immigrants are usually rootless, combined with sociological changes, the context created a search for identity and roots. In America, Pentecostalism came as an answer to this search.

In parallel, the beginning of the Church of God was a call for restoration and a literal return to the Primitive Church. It was The Christian Union committed to “restore primitive Christianity.” In its early years the Church of God focused on four main characteristics of the Church from Acts: (1) great outpouring of the Spirit, (2) great “ingathering of souls,” (3) tongues of fire and (4) spread of the Gospel. Similar to the Early Church, it began in the context of persecution, presence and parousia. While heavily persecuted the Church of God constantly remains in the presence and guidance of the Holy Spirit in a firm expectancy of the return of Christ. The Genesis of the Church of God was a restoration of the Pentecostal prayer, power and praxis of the Primitive Church.

Pentecostal Praxis

My first personal experience of the Pentecostal praxis was through the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. It took place the day after I was saved, and ever since has taken a central place in my personal life, spiritual life and ministry. The liturgy I am about to describe is a typical Communion Service in the Bulgarian Church of God. It dates back to the early 1920s when Russian immigrants to the United States were traveling back from the Azusa Street revival to Russia to preach the Good News to their people. On the way back, their ship stops for a night at the Bulgarian port of Bourgas on the Black Sea. They attended the service at the Congregational church in town, and a great number of the believers received the Spirit through their ministry. This event is considered the initiation of the Pentecostal movement in Bulgaria.

The Church of God in Bulgaria was established in the 1928 with an identical name, but independently from the Church of God (Cleveland, TN). The first link between the two churches was established in 1985. During this 65-year period, the Church of God in Bulgaria was persecuted by Orthodox and nationalistic organizations before and during the Communism Regime, and was looked upon as an extreme cult organization. Yet, during these years of underground worship, the Church of God has preserved the liturgy of the Eucharist in the grade of authenticity in which it was received.

An essential part the service is the preparation. The believers depend on the leadership of the Holy Spirit for the exact date and time of the Communion Service. Due to the lack of scheduled services in the underground church, the believers trusted in the protection of the Holy Spirit in arranging the service. Fasting is also a requirement on the day of the service.

The actual service usually takes place in the nighttime when everyone is free from work. It takes place in a believer’s home. Sometimes these services have up to fifty people in a small apartment. Worship is quiet, because any loud noise may lead to the appearance of the police.

The physical silence, however, does not limit the presence of the Holy Spirit, and even helps the believers to be more sensitive to God’s voice, which is indescribable when taking place as a group experience. The service starts with prayer, which lasts till God reveals who among the ladies is to beak the unleavened bread for the communion. After the chosen ladies leave to bake the bread, the minister delivers his communion message.

The altar call, given after the preaching, purposes to prepare the believers for Communion. Communion is not given to a person who is not saved, baptized in water and in the Holy Spirit. Therefore, after the sermon, a prayer is offered for the sick and the needy, a special prayer is prayed for repentance and the baptism of the Holy Spirit. I have personally witnessed up to thirty people saved and baptized in the Holy Spirit in a matter of minutes.

The converts are led to the river and baptized in water. This is often done in the middle of the night, when sometimes the temperature is so low that the minister and his assistants break the ice in order to baptize the convert.

The converts are welcomed back with a special song sung by the congregation. After an extended time of self-examination and the request of each believer to be forgiven by the present members of the congregation, the pastor presents the Communion to the congregation. One unleavened cake is used as a symbol of the oneness of Christ’s body. The cup of the Communion is filled with wine. The roots of this tradition can be traced back to the teachings of the first western missionaries to Bulgaria at the end of the nineteenth century, as well as the influence of the Eastern Orthodox tradition. After communion, men and women are separated for a foot washing service. At the end of the service, all are gathered for an Agape feast, which serves as a conclusion of the Communion Service.

This communion liturgy has been strictly preserved for the past hundred years by believers who have been challenged to keep their faith even with the cost of their lives through the persecution of Communism. Apart from the official doctrinal teachings of the denomination, the experience of the sacrament has been its only protector.

It would have been easier to define and reconstruct the basic list of church practices if at least a minimal structural system, formal government or doctrinal statements existed. Both the Primitive Church and Early Pentecostalism substantively lacks all of this. It was this deficit that creatively shaped the identity of the Church and presupposed its further search for primitivism.

Although the primitive communities were not the same everywhere, three practices were common for all: sharing of possessions, baptism, and communion. They were accompanied by the early liturgical formulas such as amen, hallelujah, maranatha, etc.

The message of the Primitive Church was delivered mainly through speeches (Acts 2, 7, 17, 20, etc.) and communal discussions of examples of the Bible (Acts 7; Heb. 11). It contrasted the present experience with the former lost conditions in a before-after contextual method (Rom. 7-8) and served as a practical instruction of the Christian walk (Col. 3:5ff.).

Pentecostal Power

I have heard the stories of the older Bulgarian Christians about the Communist persecution; stories of pain and suffering, horrifying the psyche and the physics of the listeners. They speak of a persecuted church whose only defender has been God. I have heard the stories of the saints of old, but I have also seen these stories turning into powerful testimonies of the powerless, who become powerful in a realm which human understanding cannot comprehend or explain. I have seen the stories of pain then become an arena for the power of God, and the saints of old holding their hands lifted up, with eyes filled with fire from above, voices that firmly declare, “Thus sayeth the Lord.” And their testimonies have become confirmation of my faith and convictions as well as the faith of many others. Their faith, rather primitive and naïve, but firmly based in God, naturally powerless but divinely powerful, has preserved their experience for us.

Theologically, preservation is an agency through which God maintains not only the existing creation, but also the properties and powers with which He has endowed them. Much had been said and written about spiritual power in the second half of the nineteenth century. The theme of “power” was clearly present in the Wesleyan tradition along with the motifs of “cleansing” and “perfection.” The effects of the spiritual baptism were seen as “power to endure, and power to accomplish.” It was also suggested that “holiness is power,” and that indeed purity and power are identical.

Nevertheless, it was recorded that in the midst of this quest for the supernatural power of the Primitive Church, the believers in Topeka, Kansas searched “through the country everywhere, …. unable to find any Christians that had the true Pentecostal power.” The Apostolic Faith began its broadcast of Pentecost with the words “Pentecost has surely come …” It further explained that the cause for this miraculous occurrence was that “many churches have been praying for Pentecost, and Pentecost has come.”

The central understanding of the spiritual power was as enduement for ministry. According to this interpretation, Christ’s promise in Acts 1:8 was seen fulfilled on the Day of Pentecost. It was intergenerational power to experience God’s grace for the moment, but also to preserve it for the generations to come, as Peter stated, “For the promise is unto you, and to your children, and to all that are afar off, even as many as the Lord our God shall call” (Acts 2:39). Furthermore, this power was interpreted as an integral part of the ministry of the Primitive Church. Since it had been lost in history, it was needed again and an immediate reclaiming was necessary. It was both an individually and corporately experienced power as it focused on both personal holy living and witnessing to the community.

The Church of God accepted both the sanctification and baptism characteristics of the power, but it interpreted the sanctification separate from the baptism with the Holy Spirit. Sanctification was divinely initiated and perfected. It was not through the believer’s self-discipline, as Wesley taught, but through the power of God alone, that the believer could be sanctified and continue to live a sanctified life free from sin. What was experienced in 1896 was definitely Pentecost, and not just any Pentecost, but was the Pentecost of the Primitive Church from Acts chapter two.

Further, interpreting the account of Acts, this power found expression in glossolalia, spiritual gifts, miracles and healings. Since, it was physically manifested in the midst of the congregation it was holistically experienced by the Christian community, and that was enough proof for its authenticity. The interpretation included expressions like dynamite, oxidite, lyidite and selenite. But the power had more than just physical manifestations. It was their only explanation of the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. It was their proof that He indeed was the Messiah. Therefore, it produced results in real-life conversions, affecting the growth of the small church in the mountain community. It was a power for witness. It was also the power that gave them strength during the numerous persecutions. Even when the church building was burned to the ground and the members were shot at and mocked, the reality of the living Church, as the Body of Christ, remained unscathed. The promised power brought meaning into the life of the Church of God.

Pentecostal Prayer

My personal experience of prayer comes from an hour between three and four o’clock in the afternoon spent every day sitting in the presence of God on an old chair in Coffee Room #3 on the fourth floor of the Men’s dorm in the Computer Technical School of Pravetz, Bulgaria. It is accompanied with the memories of leaving the dormitory through a first-floor window along with 15-20 other boys and running in the early morning snow to the small mountain Church of God through the doors of which so many have entered the glory of Heaven. And it always brings to my mind the image of my praying grandmother who forgetting the need of sleep and rest spent countless nights of prayer in the presence of the Almighty God.

If Pentecostalism has indeed discovered and acquired any of the characteristics of the Primitive Church this would be the prayer of the early saints. Prayer is also the means for universal identification with the Pentecostal movement. The Bible School of Charles Fox Parham in Topeka, Kansas had a prayer tower where prayers were ascending nightly and daily to God. It was through prayer and laying on of hands when around 11 p.m. on December 31, 1900, Agnes Ozman was baptized in the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in other tongues. Six years later the Apostolic Faith stated that the beginning of Pentecost started with prayer in a cottage meeting at 214 Bonnie Brae.

It was a timeless prayer as they wept all day and night. It was prayer for reclaiming the power from the past; prayer for the present needs, and prayer for the future return of Christ. Prayer was not only the source of divine power, but also the means for preservation of the power and the identity of the Primitive Church. Prayer was not only the request for power, but also for the personal change and preparation of the believer who was going to receive the power. The connection between power and prayer was in the spirit of the ongoing Azusa Street Revival, whose members were earnestly urged to, “Pray for the power of the Holy Ghost.”

Similarly, the Church of God based its quest for the Primitive Church in prayer. Moreover, prayer was the only way these poor, uneducated and persecuted people could find comfort for their needs and answers for their lives. Prayer was their communication with God, their worship and their only way of experiencing the divine and acquiring the supernatural. It was not a sophisticated constructive liturgy, but rather a simple deconstructive experience, where the believer was divinely liberated from the past, present and future doctrinal dogmas and human limitations.

Only then was the believer able to experience the presence of God freely. The past pain was gone, the present need was trivial and the future was in the hands of the Almighty God. Hope, faith, crying, tears and joy were all ecstatically present in the reality of prayer, because God could hear and see all. And somehow, in a ways, which remains unexplainable, mystic and supernatural, their cry to God was heard and they were indeed empowered.

It was through a fervent prayer that in the summer of 1896 in the Shearer Schoolhouse in Cherokee County, NC about 130 people received the baptism of the Holy Ghost. It was through the prayer that took place in a cottage house, after the model of the Primitive Methodists. It was through the prayer in the house of W.F. Bryant and the prayers of the men on the “Prayer Mountain.” It was like the prayer in the Upper Room in Jerusalem (Acts 2). It was through the prayer which all seekers of God prayed in their search for His presence, in their need and in their longing for life. It was through the prayer, which reclaims, experiences and preserves the true Christian identity.

Twenty years later, The First Assembly of the Church of God recommended that prayer meetings would be held weekly in the local churches. It also urged for every family to gather together in family worship and seek God, instructing their children to kneel in the presence of the Almighty. In the 1907 Consecration Service both A.J. Tomlinson and M.S. Lemons expressed their desire and willingness to pray as they worked in the ministry. To seek the power for ministry through prayer was completely in the spirit Azusa Street Revival, through which Pentecostalism addressed the world with the words, “The power of God now… “

EU approves Bulgaria’s Euro adoption despite protests

Thousands protest in Bulgaria against the Euro

Pentecostal articles for Pentecost Sunday

Offering a few recent Pentecostal articles in light of the upcoming Pentecost Sunday celebration:

- The Forgotten Azusa Street Mission: The Place where the First Pentecostals Met

- Diamonds in the Rough-N-Ready Pentecostal Series (Complete)

- 95th anniversary of the Pentecostal movement in Bulgaria

- Toward a Pentecostal Solution to the Refugee Crises in the European Union

- Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals

- Pacifism as a Social Stand for Holiness among Early Bulgarian Pentecostals

- The Practice of Corporate Holiness within the Communion Service of Bulgarian Pentecostals

- Sanctification and Personal Holiness among Early Bulgarian Pentecostals

- First Pentecostal Missionaries to Bulgaria (1920)

- Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals

- The Everlasting Gospel: The Significance of Eschatology in the Development of Pentecostal Thought

- Online Pentecostal Academic Journals

- What made us Pentecostal?

- Pentecostalism and Post-Modern Social Transformation

- Obama, Marxism and Pentecostal Identity

- Why I Decided to Publish Pentecostal Primitivism?

- Historic Pentecostal Revival Tour in Bulgaria Continues

- The Land of Pentecostals

- Pentecostal Theological Seminary Address

- A Truly Pentecostal Water Baptism

The Prism of Purity: God’s Unalterable Design

by Kathryn Donev

Aristotle was a towering intellect of his era, a philosopher brimming with ideas and insights—though not all of them aligned with truth. He posited that white was a primary color, emerging from the interplay of light and transparent substances, and that all other colors derived from a blend of white and black. Aristotle taught that light was a static quality inherent to objects, with true white as its essence, and that colors arose as deviations from this original state.

Centuries later, Isaac Newton challenged this notion. After purchasing a prism at the Stourbridge Fair in Cambridge, he observed something remarkable. When light passed through the prism, it didn’t merely adjust, but it fragmented into a spectrum of colors, revealing the rainbow. Newton reasoned that if Aristotle’s theory held, passing this refracted light through a second prism should alter the colors further. Yet, that’s not what happened. Instead, the colors recombined into white light. This demonstrated that light was not a fixed property of objects but a dynamic phenomenon capable of being split and reassembled, traveling as waves or particles. Newton’s experiments revealed that white light contained all colors, directly contradicting Aristotle’s view that light merely exposed an object’s inherent qualities.

In Genesis 6:11, we read that God looked upon an earth “corrupt in His sight and full of violence.” Humanity had strayed from God’s design, descending into chaos marked by violence, unruliness, and the normalization of homosexuality without remorse. Righteousness collapsed entirely, culminating in the Great Flood. Afterward, God set a sign in the sky. The rainbow, a phenomenon never before witnessed in history. It was more than a visual marvel; it was a masterfully crafted symbol of humanity’s connection to the Creator and the purity in which we were formed. Beyond that, it carried a profound scientific message to all creation.

When true light passes through the prism of rain, the rainbow emerges. Its source is unwavering and pure. And when that light passes through another prism, it returns to its original state of true white, undistorted and unchangeable. The prism’s ability to split white light into a rainbow reflects God’s divine order—a singular source of light unveiling a spectrum of beauty, just as His singular truth and holiness shine through the diversity of creation. The constancy of light’s nature, refracting into a rainbow yet remaining unaltered in essence, points to the immutable will of the Creator. Human sin, like the corruption described in Genesis 6:11, may cloud perception, but it cannot change the fundamental properties of light that God established.

Thus, the rainbow stands as a dual testament to God’s judgment and mercy. It is a fixed design no human can undo. Though some have co-opted it as a symbol of pride, its true meaning endures as a representation of divine order and perfection that cannot be altered. Great thinking alone, as Aristotle demonstrated, is not enough. True understanding must be anchored in unchanging truth. No matter how far we stray or how desperately we attempt to twist reality, the fundamental truth endures, steadfast and unshakable.

The rainbow, in its essence, can never deviate from its purity. It is bound by the immutable laws of its creation to reflect the full spectrum of true light. It emerges from the Creator’s design as a promise, an eternal testament woven into the fabric of the universe, incapable of being anything less than the radiant, unblemished expression of divine order. No human effort can redefine its nature or dim its brilliance; the rainbow will forever shine as a flawless symbol of its origin, a beacon of truth that cannot be bent or broken. Just as humanity cannot redefine its nature or dim its brilliance. Humanity was created in the image of God as a beacon of truth with a flawless design that needs no efforts to mutilate God’s unalterable design. We are prisms of perfect purity with a purpose.

Created on 4.8.25

30 Years of the Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago

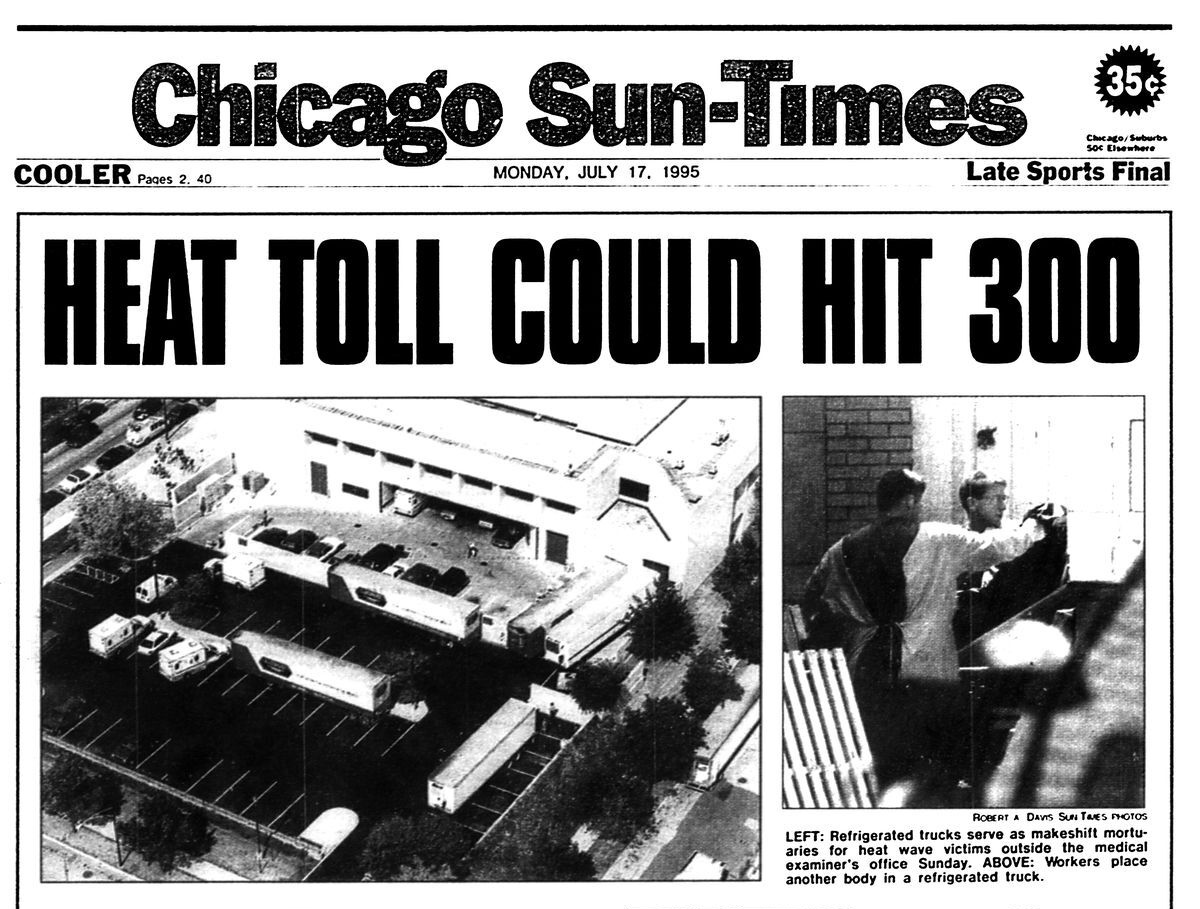

July 10, 2015 marks the 20th anniversary of the first service of the Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago in 1995.

We have told the Story of the first Bulgarian Church of God in the Untied States (read it here) on numerous occasions and it was a substantial part of our 2005 dissertation (published in 2012, see it here).

From my personal memories, the exact beginning was after Brave Heart opened in the summer of 1995 and the Narragansett Church of God closed the street for a 4th of July block party with BBQ, Chicago PD horsemen, a moonwalk and much more.

The first service in the Bulgarian vernacular was held Sunday afternoon, July 10th 1995 being the true anniversary of the Bulgarian Church in Chicago. Only about a dozen were present and the sermon I preached was from Hebrews 13:5. Unfortunately, to this day 20 years later, we cannot locate the pictures taken that day to identify those present. And some have already passed away.

Using a ministry model that later became a paradigm for starting Bulgarian churches in North America (see it in detail) the church grew to over 65 members in just a few weeks by the end of July. This was around the time the movie Judge Dread had opened and the first edition of Windows 95 was scheduled for release in Chicago. I saw them both at the mall on upper Harlem Boulevard.

The Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago followed a rich century-long tradition, which began with the establishing of Bulgarian churches and missions in 1907. (read the history) Consecutively, our 1995 Church Starting Paradigm was successfully used in various studies and models in 2003. The program was continuously improved in the following decade, proposing an effective model for leading and managing growing Bulgarian churches.

Based on the Gateway cities in North America and their relations to the Bulgarian communities across the continent, it proposed a prognosis toward establishing Bulgarian churches (see it here) and outlined the perimeters of their processes and dynamics in the near future (read in detail).

After a personal xlibris, the said prognosis were revisited in 2009 in relation to preliminary groundbreaking church work on the West Coast and then evaluated against the state of Bulgarian Churches in America at the 2014 Annual Conference in Minneapolis.

We’re yet to observe the factors and dynamics determining if Bulgarian churches across North America will follow their early 20th century predecessors to become absorbed in the local context or alike many other ethnic groups survive to form their own subculture in North America. We will know the answer for sure in another 30 years…