EU approves Bulgaria’s Euro adoption despite protests

Bulgaria’s “new” caretaker cabinet takes oath before October 27 early elections

The second Dimitar Glavchev caretaker cabinet took the oath of office in the National Assembly on August 27, hours after President Roumen Radev signed the decree naming October 27 as the date of Bulgaria’s next early parliamentary elections.

The special sitting of the National Assembly for the swearing-in, called during Parliament’s recess, lasted just eight minutes, including the oath-taking and playing of the Bulgarian and European Union anthems.

Glavchev will head an interim government with just three personnel changes compared with the one that took office in April and that subsequently underwent minor changes.

Controversial figure Kalin Stoyanov is out as caretaker Interior Minister, but his successor in that portfolio, national police chief Atanas Ilkov, has been described by some parliamentary groups as similarly serving Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF) co-leader Delyan Peevski.

Peevski said last week that were Stoyanov excluded from the next caretaker cabinet, he would place him on his list of parliamentary election candidates.

The other changes in the second Glavchev cabinet are deputy foreign minister Ivan Kondov taking over the Foreign Minister portfolio, until now held by Glavchev, and Transport Ministry legal department head Krassimira Stoyanova taking over the Transport Minister portfolio from Georgi Gvozdeikov.

The October 27 elections will be the seventh time in just more than three years that Bulgarians elect a legislature. Only two of those elections produced an elected government, neither of which served a full term in office.

Turnout in Bulgaria’s October Elections only 44%

Turnout in Bulgaria’s 29 October local elections was 44.94, in line with preliminary forecasts by sociologists. More than 2 713 000 voters went to the polls out of a total of just over 6 038 000 on the electoral rolls. This can be seen from the data published on the Central Election Commission website. In the previous local elections in 2019, the turnout in the first round was higher – 49.76%. Ballot voting will be held again on November 5, 2023. This is the 5th postpandemic elections in Bulgaria and 20th since 2005.

Government Elections in Bulgaria (2005-2022):

2005 Parliamentary Elections

2006 Presidential Elections

2007 Municipal Elections

2009 Parliamentary Elections

2009 European Parliament elections

2011 Presidential Elections

2011 Local Elections

2013 Early parliamentary elections

2014 Early Parliamentary Elections

2015 Municipal Elections

2016 Presidential election

2017 Parliamentary elections

2019 European Parliament election (23-26 May)

2019 Bulgarian local elections

2019 Municipal Elections

2021 April National Parliament election

2021 Second National Parliament election

2021 Third National Parliament and Presidential elections

2022 October elections for 48th National Assembly after the fall of a four-party coalition in June 2022.

Bulgaria’s President set a Date for this year’s Elections

Bulgaria’s President Rumen Radev signed a decree today scheduling the elections for mayors and municipal councilors for October 29.

The head of state has determined the date after a working meeting with representatives of the leadership of the Central Election Commission (CEc).

The conversation discussed the specifics of the local vote and the upcoming work on the organization of the election process. The CEC has informed the president of the technical and logistical features that the commission must comply with for the local elections and its readiness for their holding.

Here you can read about the results of a study that determined for who will one-third of Sofia residents will vote as their future mayor.

Bulgaria’s 2016 Presidential Election and Referendum Go to Runoff Ballot

Some 6.8 million Bulgarians are eligible to choose their new president who will replace incumbent Rosen Plevneliev after his five-year term ends in January. The election campaign focused mainly on the future of the European Union, relations with Russia and the threats from a possible rise in migrant inflows from neighboring Turkey

For the first time, voting in the presidential elections will be compulsory.

A tight race as expected between the two frontrunners, Parliament Speaker Tsetska Tsacheva, nominated by main ruling party GERB, and former Air Force Commander Maj Gen Rumen Radev, endorsed by the main opposition force, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP). Tsacheva, pointed by Prime Minister Boyko Borisov in October, is expected to win the first round by a narrow margin.

- Gallup International has projected a 26.7% support for Radev, while the candidate of the main ruling GERB party, Tsetska Tsacheva, has ranked second, having mastered 22.5%

- Alpha Research, another pollster offering exit poll results, suggests Radev has garnered 24.8%, with Tsacheva’s support at 23.5%.

- According to Alpha Research, third, lagging far behind, is nationalist candidate Krasimir Karakachanov, at 13.6%.

- Fourth, surprisingly, comes businessman Veselin Mareshki (9.3%) who runs as an independent candidate, followed by Reformist Bloc’s Traycho Traykov at 7.1%.

Government Elections in Bulgaria (2005-2015)

Government Elections in Bulgaria (2005-2015)

2005 Parliamentary Elections

2006 Presidential Elections

2007 Municipal Elections

2009 Parliamentary Elections

2009 European Parliament elections

2011 Presidential Elections

2011 Local Elections

2013 Early parliamentary elections

2014 Early Parliamentary Elections

2015 Municipal Elections

25 Years after Communism…

25 years in 60 seconds at the red-light…

I’m driving slowly in the dark and raining streets of my home town passing through clouds of car smoke. The gypsy ghetto in the outskirts of town is covered with the fog of fires made out of old tires burning in the yards. And the loud music adds that grotesque and gothic nuance to the whole picture with poorly clothed children dancing around the burnings.

The first red light stops me at the entrance to the “more civilized” part of the city. The bright counter right next to it slowly moves through the long 60 seconds while tiredly walking people pass through the intersection to go home and escape the cold rain. The street ahead of me is already covered with dirt and thickening layer of sleet.

This is how I remember Bulgaria of my youth and it seems like nothing has changed in the past 25 years.

The newly elected government just announced its coalition cabinet – next to a dozen like it that had failed in the past two decades. The gas price is holding firmly at $6/gal. and the price of electricity just increased by 10%, while the harsh winter is already knocking at the doors of poor Bulgarian households. A major bank is in collapse threatening to take down the national banking system and create a new crisis much like in Greece. These are the same factors that caused Bulgaria’s major inflation in 1993 and then hyperinflation in 1996-97.

What’s next? Another winter and again a hard one!

Ex-secret police agents are in all three of the coalition parties forming the current government. The ultra nationalistic party called “ATTACK” and the Muslim ethnic minorities party DPS are out for now, but awaiting their move as opposition in the future parliament. At the same time, the new-old prime minister (now in his second term) is already calling for yet another early parliamentarian election in the summer. This is only months after the previous elections in October, 2014 and two years after the ones before them on May 2013.

Every Bulgarian government in the past 25 years has focused on two rather mechanical goals: cardinal socio-economical reforms and battle against communism. The latter is simply unachievable without deep reformative change within the Bulgarian post-communist mentality. The purpose of any reform should be to do exactly that. Instead, what is always changing is the outwardness of the country. The change is only mechanical, but never organic within the country’s heart.

Bulgaria’s mechanical reforms in the past quarter of a century have proven to be only conditional, but never improving the conditions of living. The wellbeing of the individual and the pursuit of happiness, thou much spoken about, are never reached for they never start with the desire to change within the person. For this reason, millions of Bulgarians and their children today work abroad, pursuing another life for another generation.

The stop light in front of me turns green bidding the question where to go next. Every Bulgarian today must make a choice! Or we’ll be still here at the red light in another 25 years from now…

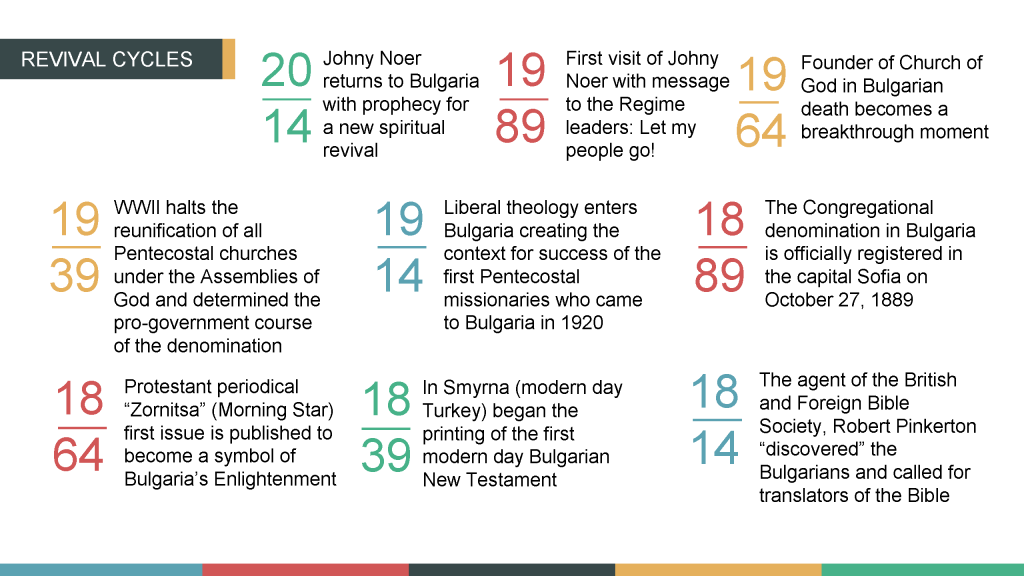

25 Year Revival Cycles in Bulgaria’s Protestant History

2014 Pastor Johny Noer visits Bulgaria with a prophecy for a new spiritual revival in the land

1989 First visit of Pastor Johny Noer in Bulgaria. The Berlin Wall fell seven months later

1964 Pastor Stoyan Tinchev of the Bulgarian Church of God passed away. This was a breakthrough moment for the ministry of the denomination, which will occupy a historical place in the Bulgarian Pentecostal movement in the next half of century

1939 In the years before WWII, Dr. Nikolas Nikoloff returned to Bulgaria in a renewed attempt to unite all Pentecostal churches in the country. Future Pentecostal Union’s president Ivan Zarev is ordained to the ministry, which determined the pro-government course the denomination would take under the Communist Regime

1914 The beginning of the Great War stopped access of American missionaries to Bulgaria and opened the doors for liberal theology to enter traditional protestant churches. This factor alone allowed the success of the first Pentecostal missionaries sent to Bulgaria by the Assemblies of God in 1920.

1889 After the bylaws of the Congregational church are accepted in the city of Pazardjik in 1888, the Congregational denomination is registered in the capital Sofia on October 27, 1889. Interestingly, exactly a century later again in the capital Sofia on October 27, 1989, the communist militia uses force to stop Green Party protestors which marks the beginning of the fall of communism in Bulgaria.

1864 The monthly protestant periodical “Zornitsa” (Morning Star) is first published to become not only the most successful protestant publication in Bulgaria, but also a symbol of Bulgaria’s Enlightenment. At the same time, ABFMC agent Charles Mors began a Bible Study in Sofia from which the first evangelical church in the capital will emerged in 1879.

1839 In Smyrna (modern day Turkey) began the printing of the first modern day Bulgarian New Testament

1814 The agent of the British and Foreign Bible Society, Robert Pinkerton “discovered” the Bulgarians within the border of the Ottoman Empire and immediately calls for translators who can translate the Bible in the local vernacular. The year marks the beginning of Protestantism in Bulgaria.

Read Also:

- Prophetic Revival in Bulgaria: The Search for Holiness Continues

- Second Varna Declaration (October 5, 2014)

Bulgaria’s Cabinet to Resign

The Oresharski cabinet will resign on July 23, Wednesday, Bulgaria’s Minister of Economy Dragomir Stoynev told Darik yesterday.

The minister emphasized that the faster the early elections, the better, because “the political crisis could affect the economy.” He also said, however, that before its resignation, the current government has to choose Bulgaria’s next EU Comissioner, who will not be withdrawn by the caretaker government.

Stoynev expressed that current Bulgarian Commissioner Kristalina Georgieva unfortunately has no chance of being nominated as High Commissioner for Foreign Affairs despite the strong support from Prime Minister Oresharski. “I’m pretty sure that her candidacy will not succeed” he noted by refusing details. As a report on the work done last year in office, Stoynev stated that Bulgaria had growth of above 1% – which has not happened since the crisis from 2009. “The Cabinet created 40,000 jobs, which has been unprecedented in the last five years,” he commented.

Minister Stoynev is against the current state budget update attempts, as he deems that unneccessary. In his opinion, the budget of NHIF also does not need to be updated. “Pouring money into an unreformed system of mismanagement will not solve the problem,” he said and recommended to look for internal reserves by restructuring the health budget.

Financial Times: Bulgaria needs stability before uncertainty

A caretaker government in Sofia will do its utmost to steady the tiller before May’s snap elections, following several weeks of street protests that toppled the previous administration and plunged Bulgaria into political uncertainty. But what happens after the poll is anybody’s guess. Many in Sofia’s political elite seem reluctant to grasp the poisoned chalice of leadership and their capacity to satisfy the demands of a restive and inchoate popular movement is limited.

On Wednesday, President Rosen Plevneliev ended weeks of speculation by naming Marin Raykov, Bulgaria’s ambassador to France, as caretaker prime minister until the May 12 elections. Raykov is a career diplomat and was deputy foreign minister under a right-of-centre government between 1998 and 2001 and again in 2009-2010 under Boyko Borisov, whose resignation as prime minister last month led to the political void which Raykov must temporarily fill. Raykov also served as an ambassador and a foreign policy chief under the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), the main opposition force. The new premier will be backed by a cabinet including three deputy prime ministers – all women – Bulgaria’s first female interior minister and a selection of other “experts” drawn from various parts of national life, particularly academia. There are also some promotions from within Borisov’s GERB party.

Bulgarian journalists have been quick to pick up on Raykov’s family background. His father, Rayko Nikolov, was a senior ambassador in the Communist era, including to the UN, Yugoslavia and France. Nikolov’s reported close links to the intelligence services come as a surprise to no-one. But of more interest is the allegation, made by the French press some years ago, that he was responsible for recruiting French politicians to work for the Soviet Union, including Charles Hernu, who went on to be defence minister in the 1980s.

Raykov’s political career on the “reformist” right but with roots among the Communist nomenklatura have led to suspicions that he is what Bulgarians gnomically call a “hidden lemon” – someone who is not what they appear to be. But Raykov’s diplomatic record suggests that he is robustly on the pro-European, rather than pro-Kremlin, side of Bulgarian politics, according Ivo Indzhev, a well-regarded Bulgarian blogger. And after all, one can’t choose one’s parents.

Dimitar Bechev, head of the Sofia office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank, says Raykov is a sound choice. “This government won’t do much beyond organise the elections,” he says. “Raykov is solid – linked to the 1990s right, but with enough credibility with all parties. He brings predictability and reassurance, as well as credibility for outsiders. He is aware of European policy issues and shows that Bulgaria will play by the rules.”

With the temporary administration in place, attention shifts to the election and what is likely to be a confused aftermath. Polls suggest GERB and the BSP are level pegging, with the largely Muslim-backed DPS and Bulgaria for the Citizens, led by former European Commissioner Meglena Kuneva, also likely to make it to the next parliament. Confusingly, BSP leader and ex-prime minister Sergey Stanishev has said he will not be premier again, while Kuneva has indicated that her party will not join a coalition.

Anthony Georgieff, a Bulgarian journalist and a vocal critic of Borisov, says the most likely scenarios as the mainstream opposition backs away from government are a discredited GERB being returned to power, considerably weakened, or the strengthening of hardline left- and right-wing forces unpalatable to Bulgaria’s EU partners. The far-right party Ataka, until recently seen as on the wane, seems to be recovering, and ultranationalists have been a significant presence at many demonstrations, along with well as anti-capitalist malcontents.

“Bulgaria’s moral crisis is reflected in the mainstream politicians refusing to take part in any coalition government of the future, and in the general public voting with their feet,” he says. Bechev is more upbeat, saying that Stanishev and Kuneva’s statements should be “taken with a pinch of salt”. He outlines a number of more moderate outcomes, including a grand coalition with GERB but without Borisov, and a BSP-DPS partnership, possibly bringing in Bulgaria for the Citizens, not dissimilar to the government from 2005 to 2009.

Whether any of these permutations will have the political will, economic resources and administrative capacity to address the demands of the street protesters – and the many Bulgarians at home who have lost faith in the political elite’s ability to deliver real change – is questionable. Demonstrations that started over power prices now encompass grievances such as corruption, authoritarianism, government links to organised crime, and privatisation. Most fundamentally, they may be about low incomes and lack of prospects in the EU’s poorest country – something that Raykov has said that he will look to address, within his capabilities. But with the eurozone, Bulgaria’s main trading and investment partner, still in crisis, and the legacy of years of maladministration at home, immediate change for the better seems unlikely.

“Unlike other crises Bulgaria has had since it shook off Communism in 1989, the current one has no easy answers because there is little if anything to look forward to, Bulgaria now being a full member of the EU and NATO,” says Georgieff. The death by self-immolation of three demonstrators since protests began certainly indicates the desperation that many Bulgarians feel. But some are hopeful that the street movement can put pressure on the next government to deliver the transparency and accountability that has been lacking from its predecessors.

NY Times: Bulgaria’s Unholy Alliances

By MATTHEW BRUNWASSER

SOFIA — His enthronement as patriarch of Bulgaria, spiritual leader of millions of Orthodox believers here, was supposed to stir pride and moral togetherness in an impoverished country confronting a vacuum in political leadership and widespread economic pain. Instead, the installation of His Holiness Neofit last month, in a ceremony replete with byzantine splendor, served as one more reminder that Bulgaria had never really thrown off the inheritance of 40 years of rigid Communist rule and all the duplicitous dealings that went with it.

Bulgaria has suffered fresh turmoil since mid-February, when nationwide protests erupted over a rise in power prices. The national government resigned in what it said was a bid to avert more bloodshed. But this week, the country went into nationwide mourning over the death of one protester, Plamen Goranov, 36, who set himself on fire in front of a public building in his hometown, Varna.

The church has played no part in calming its troubled nation. Like 11 of the 14 metropolitan bishops who make up the ruling synod of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Neofit was revealed to have a file documenting or implying cooperation with the powerful secret police under Communism. Proof of collaboration — for which the church has never apologized — was expected, but the number of bishops implicated when a state commission opened the files on church leaders in January 2012 “was beyond all expectations,” noted Momchil Metodiev, a historian who has researched the church in the Communist era.

By comparison with the 30-volume record involving Simeon, the Bulgarian Church’s current metropolitan for Western Europe, Neofit’s 16-page file was slender. While the file contained only a proposal by the authorities to recruit him as an agent and a negative assessment of his suitability for State Security work, the revelations raised tantalizing questions about whether more incriminating documents had been removed. That such questions linger, more than 20 years after Communism, illustrates Bulgarians’ messy relationship to that past.

One day after the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, the Communist dictator Todor Zhivkov, who had been in power since 1954, was deposed, not by popular uprising but in a palace coup. The politics behind the act remained murky, meaning that his removal is still a matter of dispute. Few Bulgarians can say the word “democracy” without irony or bitterness, because while they gained freedom and their country has now joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union, it has remained poor and underdeveloped, with the riches most dreamed of under capitalism reserved for the lucky, often criminally connected, few. And although State Security officially disbanded, its officials have retained a hold, contributing to the lack of clarity or debate about the past.

Many former agents went into private business and recruited wrestlers for muscle. Their networks, often criminal, gradually took over much of Bulgaria’s legitimate economy, helping to make Bulgaria notoriously corrupt, said Philip Gounev, a corruption expert at the Center for the Study of Democracy in Sofia. Similarly, the church has not faced up to its past. “Just as people say that our country is in ‘state capture’ by criminals and oligarchs who have taken control of the state, the church is in a state of ‘state capture’ by metropolitans associated with the state security police,” Mr. Gounev said.

The church counters that it is, for instance, planning to canonize martyrs from the Communist era over the next two years, making saints of those found to have died or been imprisoned for the faith among the thousands of believers who were persecuted. “We can expect to close the page of our Communist heritage by this very symbolic act,” said Desislava Panayotova, from the cultural department of the Holy Synod.

But it seems that it will take more than canonizations to restore the church’s position as a moral beacon in an increasingly secular society. After the state, the church is the second-largest landowner in the country, making it an attractive target for criminal groups. With its weak management and opaque institutions — the church does not, for instance, have a designated media spokesperson — observers say the church has remained aloof from any state efforts to clean up corruption. While many historic churches and monasteries crumble from neglect, the Bulgarian news media relay a stream of shocking stories about church officials’ luxury cars, expensive watches, shady land deals and ties to questionable businessmen.

The Stara Zagora metropolitan, Galaktion, a close rival to Neofit in the recent patriarchal election, bestowed an honorific church title on a wealthy sponsor, Slavi Binev, a former taekwando champion and owner of a security firm who is now also a member of the European Parliament. Mr. Binev was described in a 2005 WikiLeaks cable from the U.S. Embassy in Sofia as heading a group whose “criminal activities include prostitution, narcotics, and trafficking stolen automobiles.” In response, Mr. Binev told a Bulgarian newspaper that he was not perturbed to be on a list of people who were “the blossom” of Bulgarian business in the transition from Communism.

The metropolitan of Plovdiv, Nikolai, bestowed the same church title on Petar Mandzhukov, an international arms dealer, and later announced that he planned to sell his Rolex watch to pay the unpaid electricity bill for a church in his diocese, apparently hoping to quell public anger both at church riches and at the rising price of electricity that helped spark the recent protests. The church has also been accused of paying priests in cash to avoid social welfare payments and taxes.

One huge challenge is healing the post-Communist schism of 1992, when priests who said they had opposed Communism formed their own synod. Ugly disputes over church properties resulted, including physical fights. The police were called in during one particularly fierce battle over the church candle factory, a major source of income. Mr. Metodiev, the historian, who describes himself as “anti-Communist,” made a surprising discovery during research in the secret police files. “The leaders of the schismatic synod were in fact the closest allies of the Communist Party in the synod during the Communist period,” he said.

One bishop notorious for implementing State Security orders — Kalinik, the metropolitan of Vratsa — remains on the church synod today. Mr. Metodiev asserts that those with ties to State Security, particularly those recruited as young informers in the 1970s and 1980s, are now powerful, making the synod in fact more staffed by secret police than any other, including during Communism itself. “The very idea of meritocracy failed,” Mr. Metodiev said. “People are now accustomed to developing their careers due to connections. This is one of the most damaging long-term results of the power of the State Security.”

Bulgaria’s Orthodox Church Elects New Patriarch

Metropolitan Neofit of Ruse was elected Sunday as the new spiritual leader of Bulgaria’s Orthodox Christians amid social unrest threatening to throw the Balkan country in a serious political crisis. The 67-year-old Neofit was picked among three candidates shortlisted in a secret ballot by the 14 bishops that make up the Holy Synod of the church.

Metropolitan Neofit of Ruse was elected Sunday as the new spiritual leader of Bulgaria’s Orthodox Christians amid social unrest threatening to throw the Balkan country in a serious political crisis. The 67-year-old Neofit was picked among three candidates shortlisted in a secret ballot by the 14 bishops that make up the Holy Synod of the church.

The enthronement ceremony for Patriarch Neofit was held at Sofia with ongoing nationwide protests against high energy bills, poverty and corruption, and demands for radical political reforms, which forced the government to resign. Speaking at the ceremony, President Rosen Plevneliev voiced hope the new patriarch will contribute to Orthodox unity and the strengthening of the faith, and will preserve the integrity of the church.

The main challenges Neofit will face at home are addressing church unity, the church’s isolation from current public concerns, financial troubles and the dwindling number of priests and monks. Last year, a panel investigating communist-era secret services announced that 11 of the 15 metropolitans had ties to those services. Among those named was also Neofit. Over 20 Pentecostal and charismatic denominational leaders were also revealed to have been a part of a nationwide network of secret agents and handlers organized by the communist secret police. Yet, only two have resigned form their leadership positions. Alike many evangelical leaders in Bulgaria, the patriarch of the Orthodox church is elected for life.