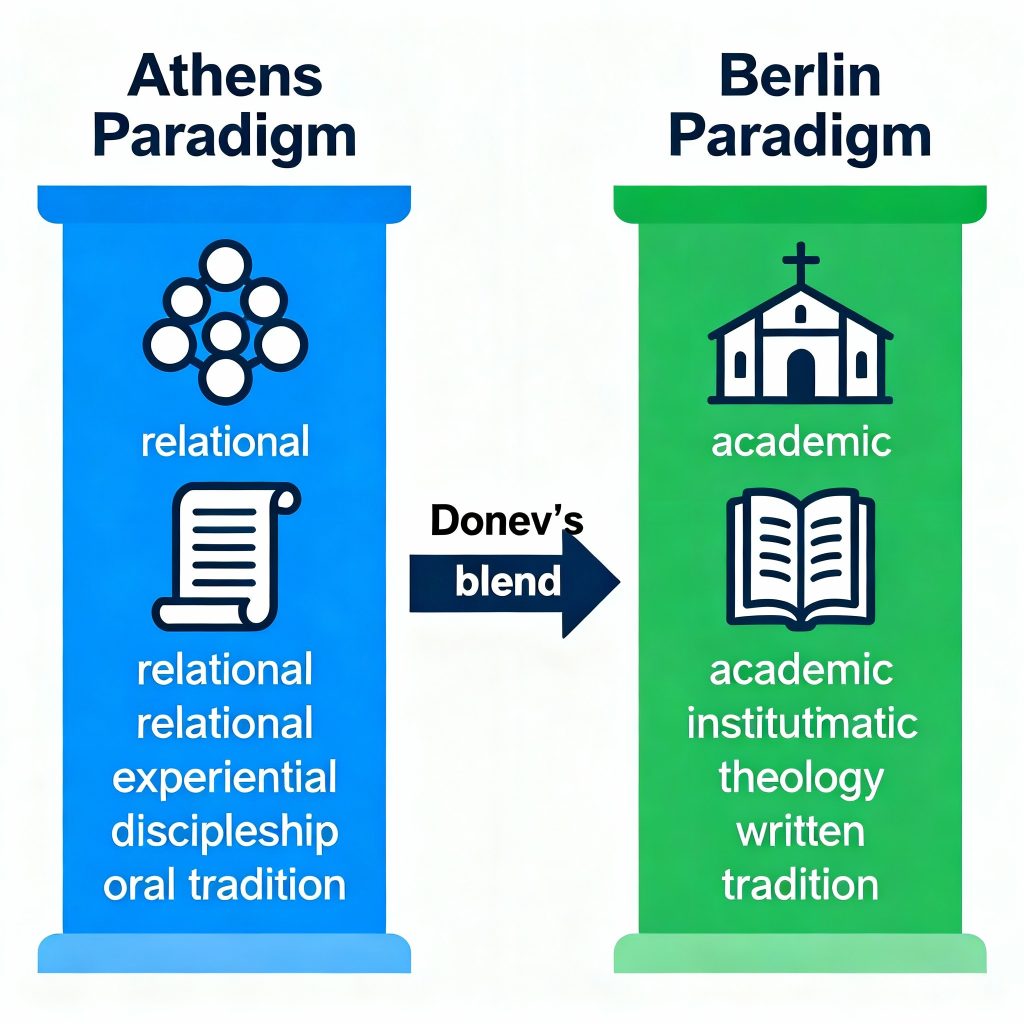

Frameworks and Key Terms by Dr. Dony Donev: Athens vs Berlin Paradigm Shift

Core Theological Frameworks

U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion

A theological framework coined during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Donev’s Intro to Digital Discipleship course at Lee University. It defines what follows Communion in Christian catechism, identifying five foundational dynamics for disciple growth: Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, and Redemptive mission.

Freedom Theology (Theology of Freedom)

Developed through Donev’s research on postcommunist Eastern Europe and the Bulgarian Protestant experience, this framework explores biblical concepts of freedom, liberation from both sin and socio-political oppression, and the church’s transformative mission as a liberator in history. It often appears in his writings as “Feast of Freedom,” drawing connections between national liberation and spiritual renewal.

Primitive Church Restorationist Model

Based in his historical research, Donev advocates for returning to the original practices and structure of the Early (Primitive) Church. This model emphasizes rediscovering authentic spiritual identity, intergenerational faith transmission, and revivalist community rooted in biblical precedent.

These frameworks have had meaningful impact on global Pentecostal studies, digital discipleship, and liberation theology, addressing contemporary challenges in theology, worship, and ecclesial practice.

Effect on Donev’s Models

-

U.S.H.E.R. Model: By anchoring his post-Communion framework in the “Athens” paradigm, Donev prioritizes unity, lived discipleship, and communal mission over purely doctrinal or institutional forms. This perspective shapes the model to valorize shared spiritual experience and relational growth, not just catechetical instruction.

-

Freedom Theology: “Athens” influences Donev’s liberation emphasis by grounding freedom in communal lived reality, while “Berlin” marks the shift toward codifying and structurally analyzing liberation.

-

Primitive Church Restoration: Donev navigates between Athens’ restorationist, dialogical church identity and Berlin’s historical-critical, analytical methodology, advocating an integration that revitalizes spiritual community while acknowledging scholarly insights.

In sum, Donev’s “Athens vs Berlin” usage intentionally blends experiential, relational Christian practice (“Athens”) with disciplined, systematic theology (“Berlin”). This dynamic underlies his frameworks, ensuring they are both deeply incarnational and critically constructive.

2026 Proclamation

Judgment has come to this region!

We were given six years to repent and to change our ways, yet we did not heed the call. We did not hear because we were distracted listening to false reports, following false gods, and walking false paths. Because of this, hardship has come upon us, and greater trials still lie ahead.

What we experienced since the Pandemic has been difficult, but what is coming will resemble the trials of Job. Only those who possess the faith of Job, those who remain steadfast and faithful, will emerge victorious on the other side. Only those who stop complaining and start moving toward conquering the promise will take the land. Only those who believe in the report of the One who brought you out of bondage will receive the blessing of milk and honey.

It does not matter that the enemy is bigger. It does not matter that their army is greater. It does not matter that there is no water or food. He is our provision and will not forsake us even though we feel as if we have been striped down to nothingness.

Stand your ground. Stand tall against demonic works in this region to which we have foolishly opened the door in our weakness. Find your backbone.

Claim your babies, claim your family, claim your promise.

Do not yield to the enemy. Not even one centimeter. Don’t even flinch in fear.

The anxiety and fear you are encountering is a lie from the pits of hell. Rebuke them in the name of Jesus.

BUT if we continue to look the other way, if we continue to welcome sin into our homes and into our sanctuaries, refusing to call sin what it is, then there will be NO hope. There will be no promise of protection. Hypocrisy will not be excused. Grace is not a license for rebellion.

Turning the house of worship into a smoke-and-mirrors spectacle is shameful. The sanctuary must remain holy. It should be a place so sacred, so charged with the presence of God, that one feels conviction even standing upon its floor. A place where no one would dare treat it casually by sipping on their starbucks. No distractions, no performances, no self-promotion.

The church can no longer function as a social club designed to entertain or accommodate the sinful, New Age practices that have crept into our region. Idolatry is wrong. Overlooking that gods have been drowned in our rivers is not acceptable. Bowing in a yoga stance to the gods is wrong.

Playing with magic is wrong. Communicating with the dead is not a game. It is wrong, even if it is your blood dabbling with it. We are to hate the sin, but love the sinner, but this does not mean to turn a blind eye to the manipulation of witchcraft and homosexuality.

Holiness is not optional! It is the standard. Period. Judgment has come to this region. Repent, repent, repent.

ENTER 2026…

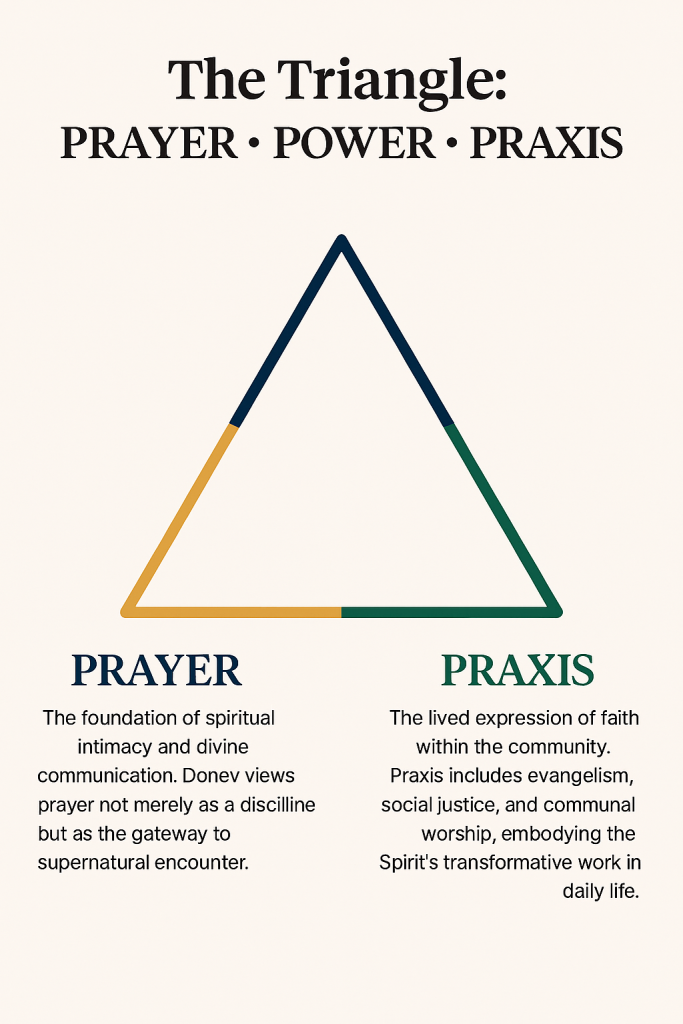

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith

This is one of Donev’s most recognized frameworks. It emphasizes three core elements of Pentecostal spirituality:

- Prayer: Seen as the starting point of spiritual communication and personal experience with God.

- Power: The manifestation of divine presence through spiritual gifts and supernatural experiences.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community, reflecting both personal and collective identity.

This triangle encapsulates the holistic nature of Pentecostalism, where theology is deeply rooted in experience rather than abstract doctrine.

Restorationist Theology

Donev builds on the idea of primitivism—a return to the faith and practices of the early church. He critiques Wesleyan frameworks like the quadrilateral (Scripture, tradition, reason, experience) as insufficient for Pentecostal identity, arguing that Pentecostalism goes beyond Wesley to reclaim the apostolic era.

Historical-Theological Contributions

In his book The Unforgotten, Donev explores the theological roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria, tracing its development through key figures like Ivan Voronaev and the influence of Azusa Street missionaries. His research highlights:

- Trinitarian theology among early Bulgarian Pentecostals, shaped by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology and Western Pentecostal doctrine.

- Free will theology, emphasizing Armenian views over Calvinist predestination, due to Bulgaria’s Orthodox heritage and missionary influences.

Other Notable Works

- The Life and Ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev: A historical-theological study of one of the pioneers of Slavic Pentecostalism.

- Doctrine of the Trinity among Early Bulgarian Pentecostals: Explores how the Trinity was experienced and understood in early Eastern European Pentecostal context

The Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Introduction

Pentecostal theology has long emphasized the experiential dimension of faith—where divine encounter, spiritual gifts, and communal expression converge. Among the contemporary voices shaping this discourse, Dony K. Donev offers a compelling framework known as the Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith, which seeks to restore the apostolic essence of early Christianity. This essay explores the theological contours of Donev’s model and compares it with other influential Pentecostal and charismatic paradigms.

The Triangle: Prayer, Power, Praxis

At the heart of Donev’s framework lies a triadic structure:

- Prayer: The foundation of spiritual intimacy and divine communication. Donev views prayer not merely as a discipline but as the gateway to supernatural encounter.

- Power: Manifested through the gifts of the Spirit—healing, prophecy, tongues, and miracles. This element reflects the Pentecostal emphasis on dunamis, the Greek term for divine power.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community. Praxis includes evangelism, social justice, and communal worship, embodying the Spirit’s transformative work in daily life.

This triangle is not hierarchical but interdependent. Prayer leads to power, power fuels praxis, and praxis deepens prayer. Donev’s model thus reflects a restorationist impulse, aiming to recover the vibrancy of the early church as seen in Acts.

Comparison with Wesleyan Quadrilateral

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral—Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience—has historically shaped Methodist and Holiness theology. Pentecostals have often adopted this model, emphasizing experience as a key source of theological reflection.

However, Donev critiques this framework as insufficient for Pentecostal identity. He argues that Pentecostalism is not merely an extension of Wesleyanism but a distinct restoration movement. While Wesley’s model is epistemological, Donev’s triangle is ontological and missional, rooted in being and doing rather than knowing.

Comparison with Classical Pentecostal Theology

Classical Pentecostalism, as shaped by early 20th-century leaders like Charles Parham and William Seymour, emphasized:

- Initial evidence doctrine: Speaking in tongues as proof of Spirit baptism.

- Dispensational eschatology: A belief in imminent rapture and end-times urgency.

- Holiness ethics: A call to moral purity and separation from the world.

Donev’s framework diverges by focusing less on doctrinal distinctives and more on spiritual vitality and historical continuity. His emphasis on praxis aligns with newer Pentecostal movements that prioritize social engagement and global mission.

Comparison with Charismatic Theology

Charismatic theology, especially within mainline and evangelical churches, often emphasizes:

- Renewal within existing traditions

- Broad acceptance of spiritual gifts

- Less emphasis on tongues as initial evidence

Donev’s triangle shares the Charismatic focus on spiritual gifts but retains a Pentecostal distinctiveness through its restorationist lens. He seeks not just renewal but recovery of primitive faith, making his model more radical in its ecclesiological implications.

Eastern European Context and Trinitarian Theology

Donev’s work is also shaped by his Bulgarian heritage. He highlights how early Bulgarian Pentecostals embraced a Trinitarian theology informed by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology. This contrasts with Western Pentecostalism’s often fragmented view of the Spirit.

His emphasis on free will theology—influenced by Arminianism and Orthodox thought—also sets his framework apart from Calvinist-leaning Charismatic circles.

Conclusion

Dony K. Donev’s Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith offers a rich, experiential, and historically grounded model for understanding Pentecostal spirituality. By centering prayer, power, and praxis, Donev reclaims the apostolic fervor of the early church while challenging existing theological paradigms. His framework stands as a bridge between classical Pentecostalism, Charismatic renewal, and Eastern Christian traditions—inviting believers into a deeper, more dynamic walk with the Spirit.

Comparative Insights from Leading Pentecostal Scholars

Gordon Fee: Scripture-Centered Pneumatology

Fee’s scholarship emphasizes the Spirit’s role in New Testament theology, particularly in Pauline writings. While he critiques traditional Pentecostal doctrines like initial evidence, he affirms the Spirit’s transformative presence. Compared to Donev, Fee’s approach is exegetical and text-driven, whereas Donev’s triangle is experiential and restorationist, prioritizing lived encounter over doctrinal precision.

Stanley M. Horton: Doctrinal Clarity and Holiness

Horton’s work, especially in Bible Doctrines, provides a systematic articulation of Pentecostal beliefs, including Spirit baptism and sanctification. His theology is deeply rooted in Assemblies of God tradition. Donev diverges by de-emphasizing denominational boundaries, focusing instead on the primitive church’s egalitarian and Spirit-led ethos.

Craig Keener: Charismatic Experience and Historical Context

Keener bridges academic rigor with charismatic openness, especially in his work on miracles and Acts. His emphasis on historical plausibility and global charismatic phenomena aligns with Donev’s praxis-driven model. However, Keener’s scholarship is more apologetic and evidential, while Donev’s triangle is formational and communal.

Frank Macchia: Spirit Baptism and Trinitarian Theology

Macchia’s theology centers on Spirit baptism as a metaphor for inclusion and transformation, often framed within Trinitarian and sacramental lenses. Donev shares Macchia’s Trinitarian depth, especially in Eastern European contexts, but leans more toward neo-primitivism and ecclesial simplicity.

Vinson Synan: Historical Continuity and Global Pentecostalism

Synan’s historical work traces Pentecostalism’s roots and global expansion. Donev builds on this by reclaiming Eastern European Pentecostal narratives, such as those of Ivan Voronaev. Both emphasize restoration, but Donev’s triangle is more prescriptive, offering a model for future church practice.

Robert Menzies: Missional and Contextual Theology

Menzies focuses on Pentecostal mission and theology in Asian contexts, often challenging Western assumptions. His emphasis on Spirit empowerment for mission resonates with Donev’s praxis element. Yet, Donev’s model is more liturgical and communal, drawing from Orthodox and Puritan influences.

Cecil M. “Mel” Robeck: Ecumenism and Pentecostal Identity

Robeck’s work on Pentecostal ecumenism and global dialogue complements Donev’s inclusive vision. Both advocate for Pentecostal distinctiveness without isolation, though Donev’s triangle is more grassroots and revivalist, aimed at local church transformation.

Implications for Church Practice

Donev’s triangle offers a practical blueprint for churches seeking renewal:

- Prayer ministries that foster intimacy and prophetic intercession.

- Power encounters through healing services and spiritual gift activation.

- Praxis initiatives like community outreach, justice advocacy, and discipleship.

Compared to other scholars, Donev’s model is less academic and more actionable, designed to reignite the apostolic fire in everyday church life.

Dr. Dony K. Donev: Introduction to John 5

-

Focus on a small part of Chapter 5; full chapter will be addressed in another talk.

-

Expository Bible study principle: do not omit what the author intends; understand the context.

-

John’s Gospel narrative in brief:

-

Chapter 1 – Creation and beginning.

-

Chapter 2 – Christ’s first miracle (water to wine).

-

Chapter 3 – Nicodemus and questions of faith.

-

Chapter 4 – Woman at the well.

-

Chapter 5 – Paralytic man (focus of this study).

-

Application: We see ourselves in these stories:

- At the well with the woman.

- With the paralytic, facing sickness or oppression.

- In creation, asking questions about beginnings.

- John’s Gospel speaks to our lives and experiences.

Verse 1: Context & Significance

-

“The Feast of the Jews” = Passover (second recorded Passover Jesus attended).

-

Chronology: Jesus ministered ~3–3.5 years, not four.

-

Johannian phrase: “After these things…” (Greek: meta tauta). Contextually links back to previous events (Samaritan woman, previous miracles).

Verse 2: Present Continuous Action

-

“Now was” vs. “there was” → emphasizes ongoing reality.

-

Location: Sheep Gate, Pool of Bethesda (“House of Mercy”), five porches.

-

Historical significance: gate restored by Nehemiah; miracles happen through preparation and prior work.

-

Water symbolism: continuous in John’s Gospel.

Verse 3: The Multitude at Bethesda

-

People lying on porches: sick, blind, lame, paralyzed, waiting for the stirring of the water.

-

Place functioned like a hospital or hospice, offering mercy but not healing.

-

Importance: highlights the need for action, faith, and not just passive waiting.

Verse 4: Angel’s Stirring of Water

-

Angel stirred water; first to enter after stirring was healed.

-

Greek: “troubling” of water → divine or angelic activity.

-

Step of faith required to enter: miracle is available, but effort is needed.

Verse 5–7: The Paralytic Man

-

Man had been ill for 38 years.

-

His theology: “A man have I none…” → depended on others, not God directly.

-

Lesson: don’t wait on another; God can act directly.

-

Human tendency: self-pity, victim mentality.

-

Jesus asks: “Do you want to be well?” – Highlights awareness, desire for change, and personal responsibility.

Verse 8: Jesus Commands Healing

-

“Rise, take up thy bed and walk.”

-

Immediate healing, resurrection-like command (Greek: anistemi).

-

Significance: ignores self-pity, performs the miracle directly.

-

Steps in healing: man immediately rises, strength restored, carries his bed/stretcher.

-

Application: miracles require obedience and action; prior failures don’t prevent success.

Verse 10–12: Testing by Religious Leaders

-

Sabbath controversy: “It is not lawful to carry thy bed.”

-

Misplaced focus: rules over divine action.

-

Observation: miracle transcends human rules; legalistic thinking may blind people to God’s power.

-

The healed man didn’t initially know who Jesus was → possible to receive miracle without knowing fully, but sustaining it requires knowing God.

Verse 14: Warning Against Sin

-

Jesus instructs: “Sin no more, lest a worse thing come unto thee.”

-

Connection: healing is not just physical but spiritual; continued obedience sustains the miracle.

Key Observations & Theological Lessons

-

The man who had no human helper was found by the Son of Man who created all men.

-

Healing is a believer’s right; Jesus administers it within the covenant of creation, restoring balance to the universe.

-

Miracles point to Christ as the central figure (water symbolism, “man of the hour”).

-

Faith, obedience, and direct encounter with God are crucial.

Practical Applications

-

Everyone can receive a miracle.

-

God makes healing and restoration possible.

-

Personal faith and obedience maintain the miracle in daily life.

-

Step of faith is often required; God provides directly.

365 Daily Thought Stirring Stories from the Field

In 1999, Dony and Kathryn established Cup & Cross Ministries International with a vision for restoration of New Testament theology and praxis. Today they have over 50 years of combined commitment to Kingdom work. This book invites you to spend a few moments each day on the field sharing their experiences of serving as pastors, evangelists, chaplains, consultants, church trainers, researchers, missionaries and educators of His Harvest around the globe.

Dony Donev: Theological Work in Pentecostal Studies

Dony Donev is known for his theological work, particularly in the context of Pentecostal studies. While he may not have a widely recognized catalog of specific terms or frameworks that have achieved broad usage, he has contributed significantly to the academic field through his research and writings.

Theological Contributions

-

Pentecostal Studies: Donev’s work often focuses on Pentecostal theology, examining its historical development, doctrinal distinctives, and contemporary implications.

-

Contextual Theology: He explores how Pentecostal theology interacts with cultural and societal contexts, particularly in Eastern Europe.

-

Pentecostal Hermeneutics: Donev might have contributed to discussions about how Pentecostals interpret the Bible, emphasizing a Spirit-led reading of the Scriptures.

Key Terms or Concepts

-

Emerging Pentecostal Identity: A possible area of focus where Donev discusses how Pentecostal identities are evolving in the modern world, including how they reconcile traditional beliefs with contemporary contexts.

-

Cultural Engagement: A term that may be used to describe his analysis of Pentecostalism’s role in engaging with and transforming culture.

For more specific terms or frameworks coined by Dony Donev, it would be beneficial to consult his published works or academic papers.

Pentecostal primitivism is a concept within Pentecostal theology emphasizing a return to the faith and practices of the early Christian church. Here’s an overview:

Key Aspects of Pentecostal Primitivism

Restoration of Apostolic Practices

- Focus on Original Christianity: Emphasizes the imitation of New Testament church dynamics, including spiritual gifts.

- Spirit-Led Worship: Encourages direct experiences with the Holy Spirit, akin to early church practices.

Doctrinal Simplicity

Primary Framework: The USHER Model of Communion

The U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion (or USHER Model)

-

Creator: Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

-

Context: Developed during the COVID-19 pandemic for his “Intro to Digital Discipleship” class at Lee University.

-

Core Purpose: To answer the question “What follows communion?” in Christian practice and catechism. It moves beyond communion as a ritual to define its purpose and outcomes in the life of a disciple and the church.

-

The Five Dynamics:

-

U – Unity: Communion fosters spiritual unity among believers, breaking down barriers and creating one body in Christ.

-

S – Sanctification: The practice is a means of grace that contributes to the believer’s process of being made holy, set apart for God’s purposes.

-

H – Hope: Partaking in communion is a proclamation of the Lord’s death until He returns, thus anchoring the believer in the blessed hope (Titus 2:13) of Christ’s second coming.

-

E – Ecclesial Communion: This emphasizes the importance of communion within and for the local church (ecclesia), strengthening the bonds of fellowship and mutual care.

-

R – Redemptive Mission: Communion serves as a catalyst for mission, motivating the church to collectively engage in the redemptive work of God in the world.

-

Other Associated Frameworks and Concepts

Dr. Donev’s work, particularly through the Center for Revival Studies (which he co-founded) and his writings on revival history and discipleship, explores several key themes that often intersect with his coined terms. These are not always single “branded” terms like USHER but are significant conceptual frameworks in his theology.

-

Digital Discipleship:

-

While not a term he solely coined, he has been a primary architect of its theological framework. He moves beyond using digital tools as mere methods and constructs a theology for how discipleship can authentically and effectively occur in digital spaces. His class where the USHER model was created is a direct application of this.

-

-

Theology of Revivalism:

-

Donev’s work heavily focuses on defining and analyzing revival, particularly from a historical (e.g., Balkan, Slavic, and Pentecostal) perspective. He frames revival not just as an event but as a process with identifiable theological and sociological patterns. His book “The Covenant of Peace: God’s Dream for the World” delves into this.

-

-

Covenant Community:

-

A recurring theme in his work is the concept of the church as a covenant community. This framework views the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants, which directly connects to the “Unity” and “Ecclesial Communion” aspects of the USHER model.

-

-

The “Why” of Discipleship:

-

Much of Donev’s writing and teaching focuses on moving beyond the “how” to the “why” of spiritual practices. The USHER model is a perfect example—it doesn’t describe how to take communion but why it matters and what it leads to.

-

Summary Table for Clarity

| Term/Framework | Description | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| USHER Model of Communion | Primary Coined Term. A 5-point framework (Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, Redemptive mission) defining the outcomes of communion. | Digital Discipleship, Catechism, Liturgy |

| Digital Discipleship | A theological framework for making disciples in online/digital environments, moving beyond mere methodology. | Modern Ministry, Post-COVID Church, Technology & Theology |

| Theology of Revivalism | A framework for understanding revival as a historical and theological process with identifiable patterns. | Church History, Pentecostal Studies, Spiritual Renewal |

| Covenant Community | A conceptual framework viewing the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants. | Ecclesiology (Doctrine of the Church), Community Formation |

In essence, while the USHER Model of Communion is his most clearly defined and coined term, Dr. Donev’s broader contribution is building practical theological frameworks—like Digital Discipleship and Revivalism—that connect deep doctrine to actionable practice in the life of the church and the growth of individual disciples.

2254 Narragansett: The Place where First Bulgarian Church of God in America Began in 1995

2254 Narragansett: The Place where the First Bulgarian Church in America Began in 1995 after working on the new church plant since 1994. With a sequence of startup events including a July 4th block party and Bulgarian picnic, first official services in Bulgarian language was held on July 10, 1995. With over a dozen Bulgarians present at 1 PM that memorable Sunday, Rev. Dony K. Donev delivered a the first message for the newly established congregation from Genesis ch. 18.

Narraganset holds a significant place in Church of God (Cleveland, TN) history. Narraganset Church of God was started by a women-preacher with only 10 members. Rev. Amelia Shumaker started the church only 15 days before the Great Depression began in 1929. https://cupandcross.com/90-years-ago

Rev. James Slay of the Narragansett Church of God in Chicago was commissioned to write the 1948 Church of God Declaration of Faith – the most fundamental document in the history of the century-old denomination. https://cupandcross.com/chicagos-narragansett

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

A multitude of documents from Church of God and other publishers testify of the rich heritage of the Narragansett Church as following:

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1953, p.23) – Pentecostal periodical content likely discussing church life or ministry in Narragansett.

- Christ’s Ambassadors Herald (July 1955, p.4) – Archive: Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center; Features youth or missions news where Narragansett likely appears in a report or story.

- Church of God Evangel (Aug 27, 1955, p.11) – Denominational publication with article or testimony likely involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1956, p.67) – Official minutes possibly documenting decisions or events relevant to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 28, 1956, p.4) – Article, testimony, or news about Pentecostal life connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 7, 1957, p.15) – News item, story, or report referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1957, p.14) – Narragansett likely cited in context of a church event or individual achievement.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1958, p.72) – Official record referencing Narragansett activities or personnel.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 21, 1958, p.15) – Article or news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1958, p.20) – Story or periodical piece potentially mentioning ministries in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1959, p.27) – Pentecostal news possibly about events in Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1960, p.82) – Minutes likely documenting decisions involving Narragansett churches or delegates.

- Church of God (Colored Work) Minutes (1960, p.156) – Record referencing Narragansett in the Black Pentecostal ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1961, p.26) – Ministry narrative or news about Narragansett participants or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1961, p.26) – Pentecostal update likely including Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1962, p.27) – Mission or church report involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 4, 1962, p.8) – Periodical item with church news or testimony from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1962, pp.24, 26) – Periodical articles likely covering events or ministries involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1962, pp.25, 27) – Reports or features about Narragansett in church or ministry context.

- Lighted Pathway (Sept 1962, p.27) – Commentary or report on Pentecostal work in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Sept 3, 1962, p.11) – Church publication news or testimony related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Dec 1962, p.25) – End-of-year feature or event report involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1963, pp.25, 27) – New Year ministry updates or personal narratives referencing Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Feb 1963, p.27) – Article tied to events or news about Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Apr 1963, p.27) – Ministry or personal story mentioning Narragansett’s Pentecostal activity.

- Lighted Pathway (May 1963, pp.24, 26) – Series of short reports or church updates involving Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (May 27, 1963, p.13) – Denominational article highlighting Narragansett members or events.

- Lighted Pathway (June 1963, pp.25, 26) – Monthly news or highlights referencing Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 3, 1963, p.2) – Ministry or event news from Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1963, p.26) – Summer reporting on church activity in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Aug 1963, p.26) – Monthly bulletin with Narragansett updates.

- Lighted Pathway (Oct 1963, p.26) – Late-year church life summary involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1963, p.26) – Ministry or church news referencing Narragansett Pentecostal community.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 4, 1963, p.23) – Publication sharing revival or missionary updates connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1964, p.98) – Official record documenting actions or ministers in Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Jan 1964, p.25) – Early-year article involving outreach efforts within Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (July 1964, p.25) – Summer feature mentioning ministry or youth activity from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 5, 1964, p.4) – Periodical covering sermon, testimony, or outreach from Narragansett.

- Church of God in Christ Women’s Int’l Convention Souvenir Journal (1966, p.33) – Biographical or feature mention related to Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Nov 1966, p.22) – Article focusing on community or youth ministry involving Narragansett.

- Lighted Pathway (Mar 1968, p.22) – Church life feature reporting mission or revival activity linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Oct 28, 1968, p.19) – Denominational story referencing Narragansett churches or workers.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1970, p.118) – Entry documenting leadership appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1974, p.266) – Proceedings referencing Narragansett ministry or district data.

- Church of God Evangel (Nov 11, 1974, p.11) – Report detailing Pentecostal efforts or individuals from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Feb 24, 1975, pp.20–22) – Consecutive articles covering regional or missionary stories with Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Apr 14, 1975, pp.18–21) – Cluster of related news items mentioning Narragansett connections.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1976, p.282) – Record noting organizational recognition involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1978, p.291) – Summary documentation listing Narragansett pastors or resolutions.

- Church of God Evangel (June 12, 1978, p.9) – News article or event centered on Pentecostal ministry in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 24, 1979, p.8) – Story or holiday report connected to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1980, p.308) – Record documenting proceedings or appointments involving Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1982, p.327) – Assembly notes on activities or delegates linked to Narragansett.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1984, p.320) – Reference to ministry developments affecting Narragansett.

- Mission America Newsletter (Jan 1984, p.3) – Mission-focused newsletter item covering Narragansett outreach.

- Church of God General Assembly Minutes (1988, p.387) – Record of ongoing ministry and leadership from Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (June 1995, p.33) – Summer news or ministry highlights connected to Narragansett.

- Lee Review (2009, p.6) – Academic or reflective article mentioning Narragansett in theological context.

- Lee Review (2009, p.163) – Further academic commentary referencing Narragansett history.

- Church of God Evangel (Jan 2009, p.29) – Article or testimony on 21st-century Pentecostal activity in Narragansett.

- Church of God Evangel (Dec 2011, p.19) – Year-end church reporting or testimony tied to Narragansett ministries.

- Living the Word: 125 Years of Church of God Ministry (2012, p.19) – Book excerpt referencing significant Narragansett milestones.

- Unto the Least of These: A History of Church of God Benevolence Ministries (2022, p.17) – Benevolence ministry history featuring Narragansett outreach.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.18) – Continuation highlighting Narragansett’s benevolence role.

- Unto the Least of These (2022, p.20) – Most current publication focusing on Pentecostal service and impact in Narragansett.

Dony Donev: Theological Framework Centered on Neo-primitivism

Dony Donev’s theological framework is centered on neo-primitivism, which he describes as a return to the “basic order of the Primitive Church of the first century”. Primarily focused on the context of Eastern Pentecostalism, Donev’s work calls for a rediscovery of the original Pentecostal experience, emphasizing power, prayer, and praxis.

Coined terms and key concepts

Neo-primitivism: This is the central concept in Donev’s framework, which he coined in his book Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved. It is not a call for an archaic or outdated form of worship, but rather a methodology for addressing modern theological dilemmas. Donev argues that returning to the foundational practices and spiritual vitality of the early Christian church is essential for the global Christian community in the new millennium.

Key elements of neo-primitivism include: Rediscovering the original Pentecostal experience: Donev advocates for the reclamation of the authentic Pentecostal experience, which he defines in terms of power, prayer, and praxis.

Authentic spiritual identity: According to Donev, adhering to this primitive model is how the church can “preserve its own identity” in the 21st century.

Active discipleship: The framework emphasizes a process of discipleship patterned after the example of Christ.

Eastern Pentecostal Tradition

While not a coined term, Donev’s work is deeply rooted in and builds upon the unique history and theology of the Eastern Pentecostal Tradition. He draws heavily from his own Bulgarian background, highlighting the historical roots of Pentecostalism in Eastern Europe, as detailed in his book The Unforgotten: Historical and Theological Roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria.

Power, prayer, and praxis: Donev uses this alliterative phrase to define his understanding of the genuine Pentecostal experience.

- Power: Refers to the supernatural empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

- Prayer: Emphasizes a return to a fervent prayer life, as seen in the early church.

- Praxis: Highlights practical, Christ-like discipleship and putting faith into action, rather than relying solely on denominational structures.

Donev’s theological concerns

Donev developed his frameworks in response to what he saw as a crisis in the modern church, which he describes as facing “new existential dilemmas”. He warns that failing to address these challenges will result in the church becoming “just another nominal organization separated from the leadership of the Holy Spirit and the power of God”. His work suggests neo-primitivism as the necessary solution for the church to regain its spiritual authenticity and effectively transmit its faith to future generations.

A Call for Righteousness over Orthodoxy