Call for Parents and Caregivers to Have Time of Uninterrupted Play with Their Children

As a Board Certified Licensed Professional Counselor with nearly 20 years of experience in the field of play therapy, I understand the vital importance of play in the life of a child. With the COVID-19 pandemic which has swept the world, our children are being exposed to stressors and events that no child should ever have to endure. Children need play in their lives now more than ever before. Play is their only way to communicate and to process these traumatic times. A time of play allows for children to increase their emotional strength and reduces stress which in turn increases our children’s immunity defenses.

It is for this reason that I feel the urgency to call all parents and caregivers to set aside a minimum of 45 minutes to 1 hour during the day to play with their children. This structured time should meet the following guidelines:

- If possible should be one parent with one child at a time even if you have to limit play to only 30 minutes

- Play time is uninterrupted with no texting, social media, online surfing or phone use of any type

- Should be in a safe place

- Parents and caregivers need to offer a time which is non-judgmental in the parameters of protection

- Needs to be led by child and not adult, offering no suggestions about what or how to play unless asked from child

- Do not interrupt the child’s process by being impatient for child to finish tasks at hand

- This is not a time for teaching. It is a time of reflecting and empathetic listening of feelings.

- Repeat back to the child their actions during play instead of offering your biased insight.

- Listen to what your children are telling you via their play

- Provide unconditional love and support

There is always time for play. It should not be underestimated. During this time of crisis it is a basic necessity and will strengthen our children. We will make it through this together.

– K. Donev, LPC/MHSP, NCC

When the Church Process Hurts our Children

Policy and procedure and process are not to be feared. Without regulation, disorder and self-empowerment become a dangerous reality. However, can we truly hear from God when we become victim to the Process; when we hide behind procedure so our earthly agenda can be met? The voice of the Process can be so overwhelming that it overshadows our judgment for Truth. Dollar signs and numbers begin to replace genuine salvation and genuine miracles and genuine Holy Ghost baptism. We become too concerned with following procedure all while hurting our brothers and sisters and our spiritual mothers and fathers. We do so with no remorse because ultimately we were faultlessly just following protocol. Nevertheless these people have a voice to process events and forgiveness can be extended in which healing can occur.

But unfortunately, the ones which we always disregard while following the Process are the little ones that do not have a voice. So I speak for the children of the church who become the real victims to the Process. I speak for the ones who remain on the sidelines in the shadows under the pews; the ones who cry out for justice with their actions because this is their only way to be heard. Acting out is their way of screaming to anyone who will hear, “Don’t forget me in your Process”. Their tears say, “Stop with the politics”. I also speak for the unborn children of an infertile womb who desire to be born into unity and love. Please do not leave our innocent heirs without a place to worship, without a pastor to lead them into God’s presence and for some, without a desire to even go to church. Is the Process, with the illusion of democracy that divides, worth loosing our children in the midst? Join in saying, “No” with our actions.

-K. Donev, LPC/MHSP, NCC

All Bulgarian children must go to school

All Bulgarian children must go to school! A new legal measure called “Highway to Knowledge” calls for police enforcement over children who do not attend public school and heavy fines on their parents.

All Bulgarian children must go to school! A new legal measure called “Highway to Knowledge” calls for police enforcement over children who do not attend public school and heavy fines on their parents.

All children who do not go to school by October 20th will be brought to school with the help of the police. Five skipped class periods will cost a $100 fine for the parents (min. monthly salary in Bulgaria is about $300)

By August 31st of the school year, each school will turn in lists of students attending along with addresses and social security numbers as part of their annual school registration. If a student does not start attending school by October 20th of the school year, a “social assistance team” will be provided to bring the student in for class. This “social assistance team” will have a policeman, a pedagogy and a counselor. At least one such team must be formed in each city or village that has at least one school. The teams will tour the homes of the students not in attendance, talk to parents and explain what the sanctions are if the children are not enrolled in a school or kindergarten. If the team does not find the child at their current address, names and data will be posted by the Ministry of Interior. These teams will also be responsible for creating an individual plan for each child and what kind of help they need to remain in the education system.

By September 30th, school principals must enter the names and the data of all students enrolled in an electronic database. Each month, the system will generate a report with all absentees and appropriate action will be taken. Pre-schoolers who have not attended school for more than three days will also be reported. The parents of these children will be fined under the School and Pre-school Education Act.

The (un)Forgotten: The Story of Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s Children

![51Sa1IcA8OL._SY344_PJlook-inside-v2,TopRight,1,0_SH20_BO1,204,203,200_[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/51Sa1IcA8OL._SY344_PJlook-inside-v2TopRight10_SH20_BO1204203200_1.jpg) The (un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

The (un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

Missions & Intercultural Studies

Dony K. Donev, D. Min.

Cup & Cross Ministries International

Presented at the 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies

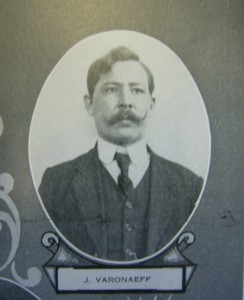

Our presentation at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis opened a door for discussion of early missionaries to Eastern Europe with a special focus on Rev. Ivan Voronaev. But the story and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev cannot be separated from his main supporter and partner in the ministry – his wife and children.

During the time of original research, it became obvious that Ivan Voronaev was successful in the ministry both in the United States and Europe only through the obedience of his family. They followed his call for missions, leaving behind the comfort of life in America. The Voronaevs sacrificed the future of their children for the unknown reality of Russia’s greatest depression. The strive for survival followed the imprisonment of both parents along with the virtually impossible task to re-immigrate from Russia and reunite in the United States, and the constant struggle to save their parents from certain death in Stalin’s consecration camps even when all hope was lost.

The Voronaevs’ story presents an early historical case study on Pentecostal missionaries and their children, not only as second generation believers, but as second generation Pentecostal immigrants as well. This example is particularly interesting since it combines both mission and immigration, as integral parts of the Pentecostal identity at the dawn of the movement. To add to this there is the relationship between missionary families and the mission-sending agency, on this occasion being the Missions Department of the Assemblies of God and in part the Russian Evangelical Diaspora.

In this context, the research on the Voronaev family has three distinct parts: (1) life in Russia and the imprisonment of the parents, Ivan and Katherine Voronaev, (2) back to America under the care of Assemblies of God Missions’ Department and (3) and the after years, with a special focus on the life and ministry of the oldest of the Voronaev’s children, Paul.

The research will utilize the available archive information at the Assemblies of God archives in Springfield, MO, as well as some Russian library material from Moscow and Kiev, which have become available after the presentation of our 2010 Voronaev paper. Special attention will be given to Paul Voronaev’s personal correspondence after his return to the United States and subsequent papers, relative to the story of the Voronaev’s children, published by him in later years. As Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s personal end is yet unknown, it is our hope that story of the Voronaev children, will provide a much needed closure to the life and ministry of one of the earliest Eastern European missionaries in Pentecostal history.

The Real Voronaev Children

![51Sa1IcA8OL._SY344_PJlook-inside-v2,TopRight,1,0_SH20_BO1,204,203,200_[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/51Sa1IcA8OL._SY344_PJlook-inside-v2TopRight10_SH20_BO1204203200_1.jpg) Reflection on The (un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

Reflection on The (un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

Kathryn N. Donev, M.S., LPC/MHSP, NBCC

The chronology of the history of events in the lives of the Voronaev children is the least to say vague and uncertain. We see only bits and pieces of their experiences. And from what we do know from theses small glimpses, the facts are so disturbing that it is easier to face reality by ignoring it. It’s much more convenient to allow the lives of the Voronaev’s children to get lost in the midst of the politics, procedure and papers (or lack thereof). But, the truth is that “The (un)Forgotten” story is not about the difficulties of anything else but the children. The children are the focus of Dr. Donev’s paper and most definitely should not be forgotten.

Reading the story of the Voronaevs takes a strong heart. It is indeed a sad one that for many of us may seem unfathomable. And yet the sparse historical accounts surrounding their life stories force the reader to confront discomfort. However, the sadist story of all is that when reading this account from the perspective of the children it was not one that I wanted to accomplish. I didn’t want to think about how the children might have felt or what they might have gone through. I refused because it was too painful. It took too much emotional anguish to even think about the pain and trauma that these children went through. Because of my refusal to contemplate the trials these children endured, I was unable to be empathetic. I was powerless to even begin to comprehend what might have gone through the minds of the children who witnessed and experienced events no child should have to. I can’t imagine what it would have been like to be a child with no “home” or much less no country. I was not able to walk a mile in their shoes. I have no idea what it is or would be like to live under Communism or to be the child of a missionary family who had so many struggles, which is putting it lightly only so I can verbalize this unfortunate reality.

When a child is in any manner separated from their parents there becomes a disconnect like no other in which a child begins to have self-doubt, insecurity and uncertainty. When this bond is ripped apart it leaves behind feelings of anxiety and guilt. Yet when a child first hand experiences a parent being dragged off by Communist police in front of them, this leaves an entirely different scar, one which never heals. It is a scar so deep, filled with enormous traumatic stress which no one could possibly imagine. Not to mention the other dynamics of immigrations and foster care that the Voronaev children endured. These children no doubt were left with feelings of loneliness and rejection in one uncertain situation after the other.

So when we look back and we read the history of the complications of obtaining visas and the difficult times of providing a place for these children to stay in addition to worrying about the financial means to do so; when we look at the bickering and shady details of people’s character, we must not over look that there where real children suffering in the midst of the chaos. They were not just characters of a story or pawns in a game. They were real even though they were only foreigners of poor missionaries. They have stories to tell. They have a voice which must be heard. They most certainly were not listened too while they were alive so let us at least do them the justice of listening to their whispers beyond the grave and hear their pain, hear their trials and hear their plea to leave the politics behind and begin to see the true reality of missions work. Too often in the world of ministry, the children are the ones who suffer the most and it is quite unfortunate that the littlest ones go unheard. We must speak for the least of these among us. We can not remain silent.

The Real Voronaev Children

Reflection on The (un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

The chronology of the history of events in the lives of the Voronaev children is the least to say vague and uncertain. We see only bits and pieces of their experiences. And from what we do know from theses small glimpses, the facts are so disturbing that it is easier to face reality by ignoring it. It’s much more convenient to allow the lives of the Voronaev’s children to get lost in the midst of the politics, procedure and papers (or lack thereof). But, the truth is that “The (un)Forgotten” story is not about the difficulties of anything else but the children. The children are the focus of Dr. Donev’s paper and most definitely should not be forgotten.

Reading the story of the Voronaevs takes a strong heart. It is indeed a sad one that for many of us may seem unfathomable. And yet the sparse historical accounts surrounding their life stories force the reader to confront discomfort. However, the sadist story of all is that when reading this account from the perspective of the children it was not one that I wanted to accomplish. I didn’t want to think about how the children might have felt or what they might have gone through. I refused because it was too painful. It took too much emotional anguish to even think about the pain and trauma that these children went through. Because of my refusal to contemplate the trials these children endured, I was unable to be empathetic. I was powerless to even begin to comprehend what might have gone through the minds of the children who witnessed and experienced events no child should have to. I can’t imagine what it would have been like to be a child with no “home” or much less no country. I was not able to walk a mile in their shoes. I have no idea what it is or would be like to live under Communism or to be the child of a missionary family who had so many struggles, which is putting it lightly only so I can verbalize this unfortunate reality.

When a child is in any manner separated from their parents there becomes a disconnect like no other in which a child begins to experience self-doubt, insecurity and uncertainty. When this bond is ripped apart it leaves behind feelings of anxiety and guilt. Yet when a child first hand experiences a parent being dragged off by Communist police in front of them, this leaves an entirely different scar, one which never heals. It is a scar so deep, filled with enormous traumatic stress which no one could possibly imagine. Not to mention the other dynamics of immigrations and foster care that the Voronaev children endured. These children no doubt were left with feelings of loneliness and rejection in one uncertain situation after the other.

So when we look back and we read the history of the complications of obtaining visas and the difficult times of providing a place for these children to stay in addition to worrying about the financial means to do so; when we look at the bickering, the perhaps shady details of people’s character and church politics, we must not over look that there where real children suffering in the midst of the chaos. They were not just characters of a story or pawns in a game. They were real even though they were only foreigners and they were only children of poor missionaries. They have stories to tell. They have a voice which must be heard. They most certainly were not listened too while they were alive so let us at least do them the justice of listening to their whispers beyond the grave and hear their pain, hear their trials and hear their plea to leave the politics behind and begin to see the true reality of missions work. Too often in the world of ministry, the children are the ones who suffer the most and it is quite unfortunate that the littlest ones go unheard. We must speak for the least of these among us. We can not remain silent.

Kathryn N. Donev, M.S., LPC/MHSP, NBCC

(un)Forgotten Story of the Voronaev Children

For if history indeed forms our identity, we are left without identity once we forget our history. Yes, we still have feature ahead of us, but it is disconnected from our past and from our experience. It is disconnected from our identity and from our story. We still have a future when we forget our history, but it is not our future – it is someone else’s. It is the future someone else wants us to have…

The (un)Forgotten: The Story of Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s Children

Our presentation at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis opened a door for discussion of early missionaries to Eastern Europe with a special focus on Rev. Ivan Voronaev. But the story and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev cannot be separated from his main supporter and partner in the ministry – his wife and children.

Our presentation at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis opened a door for discussion of early missionaries to Eastern Europe with a special focus on Rev. Ivan Voronaev. But the story and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev cannot be separated from his main supporter and partner in the ministry – his wife and children.

During the time of original research, it became obvious that Ivan Voronaev was successful in the ministry both in the United States and Europe only through the obedience of his family. They followed his call for missions, leaving behind the comfort of life in America. The Voronaevs sacrificed the future of their children for the unknown reality of Russia’s greatest depression. The strive for survival followed the imprisonment of both parents along with the virtually impossible task to re-immigrate from Russia and reunite in the United States, and the constant struggle to save their parents from certain death in Stalin’s consecration camps even when all hope was lost.

The Voronaevs’ story presents an early historical case study on Pentecostal missionaries and their children, not only as second generation believers, but as second generation Pentecostal immigrants as well. This example is particularly interesting since it combines both mission and immigration, as integral parts of the Pentecostal identity at the dawn of the movement. To add to this there is the relationship between missionary families and the mission-sending agency, on this occasion being the Missions Department of the Assemblies of God and in part the Russian Evangelical Diaspora.

In this context, the research on the Voronaev family has three distinct parts: (1) life in Russia and the imprisonment of the parents, Ivan and Katherine Voronaev, (2) back to America under the care of Assemblies of God Missions’ Department and (3) and the after years, with a special focus on the life and ministry of the oldest of the Voronaev’s children, Paul.

The research will utilize the available archive information at the Assemblies of God archives in Springfield, MO, as well as some Russian library material from Moscow and Kiev, which have become available after the presentation of our 2010 Voronaev paper. Special attention will be given to Paul Voronaev’s personal correspondence after his return to the United States and subsequent papers, relative to the story of the Voronaev’s children, published by him in later years. As Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s personal end is yet unknown, it is our hope that story of the Voronaev children, will provide a much needed closure to the life and ministry of one of the earliest Eastern European missionaries in Pentecostal history.