Bulgarian Churches in Crete (2017 Report)

Love of Christ Bulgarian Church – Yarapetra, Crete

Love of Christ Bulgarian Church – Yarapetra, Crete

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Bulgarian Churches in England (2017 Report)

#1 Gateway House, John Wilson Street, London, SE18 6DU

#2 CHRIST CHURCH SCHOOL 1 ROBINSON STREET LONDON SW3 4AA

#3 KT Summit House, 100 Hanger Lane, London W5 1EZ www.bgministrieslondon.co.uk

#4 Bulgarian Church River Of Life London 27 Elm Grove Road, Ealing, W53JH

#5 http://www.bg4christ.com

#6 110 Middle Abbey St., Dublin

#7 1 Little Barrack St, Armagh. BT60 1AD

#8 196 High Street, Stratford, London, E15 2NE

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches on the West Coast (2017 Report)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches – West Coast (2017 Report)

- Los Angeles (occasional/outreach of the Foursquare Church – Mission Hills, CA)

- Las Vegas (outreach of the Foursquare Church – http://lasvegaschurch.tv)

- San Francisco (occasional/inactive since 2012, Berkeley University/Concord, CA)

- Phoenix, AX (occasional/outreach)

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Canada (2017 Report)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches Canada (2017 Report)

- Toronto (inactive since 2007)

- Good News Toronto/Slavic – 869 Pape Ave. Toronto, Ontario, ON M4K 3T7 (active since 2009)

- Montreal (occasional/inactive since 2010)

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Texas (2017 Report)

Dallas: 2435 East Hebron Parkway Carrollton, Texas 75010 (outreach of the Assemblies of God – Carrollton, TX)

Dallas: 2435 East Hebron Parkway Carrollton, Texas 75010 (outreach of the Assemblies of God – Carrollton, TX)

Houston: 6400 Woodway Drive (building #C), Houston, Texas 77057 (inactive/occasional since 2012)

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

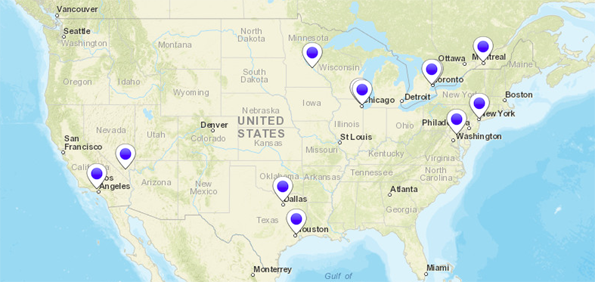

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in America (2017 Report)

CURRENTLY ACTIVE CHURCHES/CONGREGATIONS:

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Chicago (2017 Report)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Texas (2017 Report)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches – West Coast (2017 Report)

- Los Angeles (occasional/outreach of the Foursquare Church – Mission Hills, CA)

- Las Vegas (outreach of the Foursquare Church – http://lasvegaschurch.tv)

- San Francisco (occasional/inactive since 2012, Berkeley University/Concord, CA)

- Phoenix, Arizona

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches Canada (2017 Report)

- Toronto (inactive since 2007)

- Toronto/Slavic (active since 2009)

- Montreal (occasional/inactive since 2012)

Atlanta (active since 1996)

CURRENTLY INACTIVE CHURCHES/CONGREGATIONS:

- New York, NY (currently inactive)

- Buffalo, NY (occasional/inactive)

- Jacksonville, FL (occasional/inactive since 2014)

- Ft. Lauderdale / Miami (currently inactive)

- Washington State, Seattle area (currently inactive)

- Minneapolis, MN (occasional/inactive since 2015)

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

In May 1907, sponsored by the Chicago Tract Society, Petko Vasilev opened the Bulgarian Christian House in Chicago. The facilities had beds and a kitchen and served as a hotel and a shelter for new immigrants. In 1908, the name was changed to Bulgarian Christian Society and later was relocated several times.

A second similar work was started at the same time by Daniel Protoff called the Russian Christian Mission. Located in Chicago, it supported church services and a Bible school. In 1909, the City Missionary Society called Basil Keusseff to lead the mission. Keusseff was a Bulgarian born minister who was converted in Romania and was a graduate of the school in Samokov and Cliff College in Sheffield, England. In the 1890s, Keusseff pastored the Baptist church in Lom and then moved to Pittsburgh where he worked with Robert Bamber, pastor of the Turtle Creek Christian Church. The mission ministered to Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian and Turkish minorities.

Around 1910, the ministry of the Bulgarian Christian Society was aided by Reverend Paul Mishkoff, a student at Moody Bible Institute. Coming from a poor but strong Protestant family, Mishkoff was called to preach at a very early age. He studied in the school at Samokov and was often sent to preach in the nearby villages. After finishing the school, Mishkoff decided to come and study at the Moody Bible Institute. He was helped by a Methodist missionary who gave him four dollars – the price of a third-class ticket from Sofia to New York where he was put on the immigrant’s train to Chicago. He was denied admission to Moody with the explanation that there was neither room nor funds for him. With no job and no money, the young preacher had to find food at the saloons where it was offered free for ones who drank. During his struggles, Mishkoff had lost all his possessions except a pocket size New Testament. In his personal story, he recalled, “But I had the copy of the Bulgarian Testament in my pocket not only to keep it, but to read it when I was sitting on the benches of the Union Station and other public places night after night. My soul was wakened anew. An ambition was roused in me: I must prepare myself for a preacher any way.” Through a financial miracle, Mishkoff was eventually able to graduate from the Moody Bible Institute. During the course of his studies, he was supported by Chicago Tract Society and he was able to minister to the 5,000 Bulgarians living in Chicago.

Around 1910, the Bulgarian Christian Society established a library which served the Bulgarian community for over twenty years. The congregation of the mission numbered about fifty. The ministry included English classes and immigration law seminars.

Several changes in the leadership of the mission began in 1921. In 1924, the mission was headed by Zaprian Vidoloff and the mission was renamed the Bulgarian Christian Mission. Vidoloff was a graduate of the Samokov School in 1910, a student of philosophy at the University of Sofia and a graduate of Union Theological College in Chicago. He entered pastoral ministry in 1915 and later served as the secretary of the Baptist Union. At the same time, he was secretary of the Bulgarian legation in Washington, D.C. from 1921 to 1923.

All Bulgarian religious organizations initiated by evangelicals before 1930 existed as missions. In February 1932, the First Bulgarian Church pastored by Joseph Hristov was started in Chicago.

July 10, 2015 marked the 20th anniversary of the first service of the first Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago in 1995.

July 10, 2015 marked the 20th anniversary of the first service of the first Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago in 1995.

We have told the Story of the first Bulgarian Church of God in the Untied States (read it here) on numerous occasions and it was a substantial part of our 2005 dissertation (published in 2012, see it here).

From my personal memories, the exact beginning was after Brave Heart opened in the summer of 1995 and the Narragansett Church of God closed the street for a 4th of July block party with BBQ, Chicago PD horsemen, a moonwalk and much more.

The first service in the Bulgarian vernacular was held Sunday afternoon, July 10th 1995 being the true anniversary of the Bulgarian Church in Chicago. Only about a dozen were present and the sermon I preached was from Hebrews 13:5. Unfortunately, to this day 20 years later, we cannot locate the pictures taken that day to identify those present. And some have already passed away.

Using a ministry model that later became a paradigm for starting Bulgarian churches in North America (see it in detail) the church grew to over 65 members in just a few weeks by the end of July. This was around the time the movie Judge Dread had opened and the first edition of Windows 95 was scheduled for release in Chicago. I saw them both at the mall on upper Harlem Boulevard.

The Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago followed a rich century-long tradition, which began with the establishing of Bulgarian churches and missions in 1907. (read the history) Consecutively, our 1995 Church Starting Paradigm was successfully used in various studies and models in 2003. The program was continuously improved in the following decade, proposing an effective model for leading and managing growing Bulgarian churches.

Based on the Gateway cities in North America and their relations to the Bulgarian communities across the continent, it proposed a prognosis toward establishing Bulgarian churches (see it here) and outlined the perimeters of their processes and dynamics in the near future (read in detail).

After a personal xlibris, the said prognosis were revisited in 2009 in relation to preliminary groundbreaking church work on the West Coast and then evaluated against the state of Bulgarian Churches in America at the 2014 Annual Conference in Minneapolis.

We’re yet to observe the factors and dynamics determining if Bulgarian churches across North America will follow their early 20th century predecessors to become absorbed in the local context or alike many other ethnic groups survive to form their own subculture in North America. We will know the answer for sure in another 20 years…

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Chicago (2017 Report)

Bulgarian Church of God in Chicago

2254 North Narragansett Ave, Chicago

GraceInternational.TV

Active since 1995

New Life Bulgarian Evangelical Church

1480 Oakton St – Des Plaines, IL 60018

Active since 1997

Word of Faith and Life

916 E Central Rd

Arlington Heights, IL 60005

http://www.bulgarianfamily.org/

Active since 1998

Bulgarian Baptist Church

6334 W Diversey Ave.

Chicago, IL 60639

Active since 2005

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

110 Years Ago the First Bulgarian Mission in Chicago was Started

In May 1907, sponsored by the Chicago Tract Society, Petko Vasilev opened the Bulgarian Christian House in Chicago. The facilities had beds and a kitchen and served as a hotel and a shelter for new immigrants. In 1908, the name was changed to Bulgarian Christian Society and later was relocated several times.

In May 1907, sponsored by the Chicago Tract Society, Petko Vasilev opened the Bulgarian Christian House in Chicago. The facilities had beds and a kitchen and served as a hotel and a shelter for new immigrants. In 1908, the name was changed to Bulgarian Christian Society and later was relocated several times.

A second similar work was started at the same time by Daniel Protoff called the Russian Christian Mission. Located in Chicago, it supported church services and a Bible school. In 1909, the City Missionary Society called Basil Keusseff to lead the mission. Keusseff was a Bulgarian born minister who was converted in Romania and was a graduate of the school in Samokov and Cliff College in Sheffield, England. In the 1890s, Keusseff pastored the Baptist church in Lom and then moved to Pittsburgh where he worked with Robert Bamber, pastor of the Turtle Creek Christian Church. The mission ministered to Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian and Turkish minorities.

Around 1910, the ministry of the Bulgarian Christian Society was aided by Reverend Paul Mishkoff, a student at Moody Bible Institute. Coming from a poor but strong Protestant family, Mishkoff was called to preach at a very early age. He studied in the school at Samokov and was often sent to preach in the nearby villages. After finishing the school, Mishkoff decided to come and study at the Moody Bible Institute. He was helped by a Methodist missionary who gave him four dollars – the price of a third-class ticket from Sofia to New York where he was put on the immigrant’s train to Chicago. He was denied admission to Moody with the explanation that there was neither room nor funds for him. With no job and no money, the young preacher had to find food at the saloons where it was offered free for ones who drank. During his struggles, Mishkoff had lost all his possessions except a pocket size New Testament. In his personal story, he recalled, “But I had the copy of the Bulgarian Testament in my pocket not only to keep it, but to read it when I was sitting on the benches of the Union Station and other public places night after night. My soul was wakened anew. An ambition was roused in me: I must prepare myself for a preacher any way.” Through a financial miracle, Mishkoff was eventually able to graduate from the Moody Bible Institute. During the course of his studies, he was supported by Chicago Tract Society and he was able to minister to the 5,000 Bulgarians living in Chicago.

Also in 1910, the Bulgarian Christian Society established a library which served the Bulgarian community for over twenty years. The congregation of the mission numbered about fifty. The ministry included English classes and immigration law seminars. Several changes in the leadership of the mission began in 1921. In 1924, the mission was headed by Zaprian Vidoloff and the mission was renamed the Bulgarian Christian Mission. Vidoloff was a graduate of the Samokov School in 1910, a student of philosophy at the University of Sofia and a graduate of Union Theological College in Chicago. He entered pastoral ministry in 1915 and later served as the secretary of the Baptist Union. At the same time, he was secretary of the Bulgarian legation in Washington, D.C. from 1921 to 1923.

All Bulgarian religious organizations initiated by evangelicals before 1930 existed as missions. In February 1932, the First Bulgarian Church pastored by Joseph Hristov was started in Chicago.

How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

The Unrealized Spiritual Harvest of Bulgarian Churches in North America

….A closer examination of the ministry and structure of the network of Bulgarian churches in North America will give answers to essential issues of cross-cultural evangelism and ministry for the Church of God. Unfortunately, until now very little has proven effective in exploring, pursuing and implementing cross-cultural paradigms within the ministry opportunities in communities formed by immigrants from post-Communist countries. As a result, these communities have remained untouched by the eldership and resources available within the Church of God denomination. There are presently no leaders trained by the Church of God for the needs of these migrant communities. Thus, a great urban harvest in large metropolises, where the Church of God has not been historically present in a strong way, remains ungathered. Although, through these communities, the Church of God has the unique opportunity to experience the post-Communist revival from Eastern Europe in a local Western setting… (p.84, Chapter III: Contextual Assessment, Historical Background, Structural Analyses and Demographics of Immigration in a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today) Read complete paper (PDF)

….A closer examination of the ministry and structure of the network of Bulgarian churches in North America will give answers to essential issues of cross-cultural evangelism and ministry for the Church of God. Unfortunately, until now very little has proven effective in exploring, pursuing and implementing cross-cultural paradigms within the ministry opportunities in communities formed by immigrants from post-Communist countries. As a result, these communities have remained untouched by the eldership and resources available within the Church of God denomination. There are presently no leaders trained by the Church of God for the needs of these migrant communities. Thus, a great urban harvest in large metropolises, where the Church of God has not been historically present in a strong way, remains ungathered. Although, through these communities, the Church of God has the unique opportunity to experience the post-Communist revival from Eastern Europe in a local Western setting… (p.84, Chapter III: Contextual Assessment, Historical Background, Structural Analyses and Demographics of Immigration in a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today) Read complete paper (PDF)