JESUS IS IN EVERY BOOK OF THE BIBLE

Comments Off on JESUS IS IN EVERY BOOK OF THE BIBLE

In Genesis, Jesus Christ is the seed of the woman.

In Exodus, He is the passover lamb.

In Leviticus, He is our high priest.

In Numbers, He is the pillar of cloud by day and the pillar of fire by night.

In Deuteronomy, He is the prophet like unto Moses.

In Joshua, He is the captain of our salvation.

In Judges, He is our judge and lawgiver.

In Ruth, He is our kinsman redeemer.

In 1st and 2nd Samuel, He is our trusted prophet.

In Kings and Chronicles, He is our reigning king.

In Ezra, He is the rebuilder of the broken down walls of human life.

In Esther, He is our Mordecai.

In Job, He is our ever-living redeemer.

In Psalms, He is our shepherd.

In Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, He is our wisdom.

In the Song of Solomon, He is the loving bridegroom.

In Isaiah, He is the prince of peace.

In Jeremiah, He is the righteous branch.

In Lamentations, He is our weeping prophet.

In Ezekiel, He is the wonderful four-faced man.

In Daniel, He is the forth man in life’s “fiery furnace.”

In Hosea, He is the faithful husband, forever married to the backslider.

In Joel, He is the baptizer with the Holy Ghost and fire.

In Amos, He is our burden-bearer.

In Obadiah, He is the mighty to save.

In Jonah, He is our great foreign missionary.

In Micah, He is the messenger of beautiful feet.

In Nahum, He is the avenger of God’s elect.

In Habakkuk, he is God’s evangelist, crying, “revive thy work in the midst of the years.”

In Zephaniah, He is our Saviour.

In Haggai, He is the restorer of God’s lost heritage.

In Zechariah, He is the fountain opened up in the house of David for sin and uncleanness.

In Malachi, He is the Sun of Righteousness, rising with healing in His wings.

In Matthew, He is King of the Jews.

In Mark, He is the Servant.

In Luke, He is the Son of Man, feeling what you feel.

In John, He is the Son of God.

In Acts, He is the Savior of the world.

In Romans, He is the righteousness of God.

In 1st Corinthians, He is the Rock that followed Israel.

In 2nd Corinthians, He is the Triumphant One, giving victory.

In Galatians, He is your liberty; He sets you free.

In Ephesians, He is Head of the Church.

In Philippians, He is your joy.

In Colossians, He is your completeness.

In 1st and 2nd Thessalonians, He is your hope.

In 1st Timothy, He is your faith.

In 2nd Timothy, He is your stability.

In Philemon, He is your Benefactor.

In Titus, He is truth.

In Hebrews, He is your perfection.

In James, he is the Power behind your faith.

In 1st Peter, He is your example.

In 2nd Peter, He is your purity.

In 1st John, He is your life.

In 2nd John, He is your pattern.

In 3rd John, He is your motivation.

In Jude, He is the foundation of your faith.

In Revelation, He is your coming King.

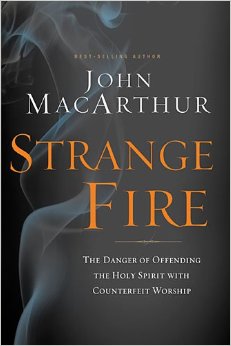

5 Reviews of MacArthur’s “Strange Fire”

Comments Off on 5 Reviews of MacArthur’s “Strange Fire”

![cropped-Synan[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/cropped-Synan1.jpg) John MacArthur Strikes Again with Strange Fire

John MacArthur Strikes Again with Strange Fire

By Vinson Synan

John MacArthur, the Calvinist, Fundamentalist, Cessationist preacher from California has done it again. With his newest attack on Pentecostals and Charismatics, Strange Fire, MacArthur, like Don Quixote tilting at windmills, continues his hopeless quest to put an end to the most energetic and fastest growing group of Christians in the world. MacArthur never quits. This is his third book on the subject, and perhaps his last. [Read more]

Frank Macchia on the Gifts of God to the Church

Frank Macchia on the Gifts of God to the Church

In the context of this hoopla over cessationism, it might be interesting to see how the issue of spiritual gifts was dealt with in the first round of international talks between the World Alliance of Reformed Churches and the Pentecostals (of which I was a participant). We agreed together that all of the gifts from the New Testament have value today, but that both global church families tended to favor different lists of gifts from the New Testament. In response, we affirmed that no single list of gifts is to be held up as all determinative for judging the quality of a church’s spirituality and that both sides must expand its horizonsby embracing the value of the gifts cherished by the other side… [Read more]

John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, Reviewed by R. Loren Sandford

Strange Fire by John MacArthur is basically an attack on anything and everything related to the Charismatic Movement and the various movements descended from it, as if the whole of it were composed of one monolithic set of doctrines and practices that all of us espouse. It invalidates anything that smacks of the supernatural or of emotion freely expressed in God’s presence. MacArthur pours his vitriol – and I mean vitriol – through the filter of his own prejudices and theological presuppositions in a way that blinds… [Read more]

![ruthven_small[1]](http://pneumareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ruthven_small1.jpg) John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, A Brief Biblical Response by Jon Ruthven

John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, A Brief Biblical Response by Jon Ruthven

As we shall see, John MacArthur’s abhorrence of “further revelation” via prophecy and related spiritual gifts derives, not from scripture, but from the frustration of Calvinists under Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) of watching so many of their members defect to the Quakers, the crazy charismatics of the time. People were falling down, making a lot of noise and encountering Jesus in visions, prophecies, and healings. Sound familiar? Calvinist scholastics responded to this outrage with the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF)—often now regarded as the gold standard…

[Read more]

![hyatt_1-140x205[1]](http://pneumareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/hyatt_1-140x2051.gif) John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, Reviewed by Eddie L. Hyatt

John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, Reviewed by Eddie L. Hyatt

As a life-long Pentecostal-Charismatic, I recommend that every Pentecostal-Charismatic leader read Strange Fire by John MacArthur. I say this because we need to see how the bizarre “spiritual” behavior and doctrinal extremes by some in our movement are viewed by those on the outside and are used to whitewash the entire movement. We have done a very poor job of addressing these problems from within, so I do not doubt that God has raised up a voice that is fundamentally opposed to our movement to address these extremes. If God could use a pagan Babylonian king to discipline his people Israel for their sins(Jeremiah 25:8-11), could he not use a merciless fundamentalist preacher… [Read more]

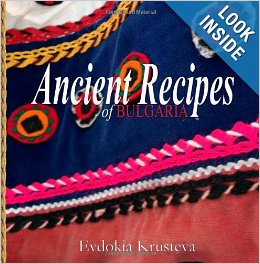

Ancient Recipes of Bulgaria

Comments Off on Ancient Recipes of Bulgaria

This cookbook features nearly two dozen truly ancient recipes of Bulgarian cooking. Some of these dishes are distant relatives to ones found in ancient Roman manuscripts believed to have been compiled in the late 4th or early 5th century AD. Others are among those far before the time of Christ. As Bulgaria is a country of oral history, recipes are typically not written, but passed down from one generation to the next by experiencing the method of preparation. With nearly every dish in Bulgarian cooking comes a story and custom. This cookbook attempts to preserve these hundred year old stories for many years to come so they can continue to be passed down.

This cookbook features nearly two dozen truly ancient recipes of Bulgarian cooking. Some of these dishes are distant relatives to ones found in ancient Roman manuscripts believed to have been compiled in the late 4th or early 5th century AD. Others are among those far before the time of Christ. As Bulgaria is a country of oral history, recipes are typically not written, but passed down from one generation to the next by experiencing the method of preparation. With nearly every dish in Bulgarian cooking comes a story and custom. This cookbook attempts to preserve these hundred year old stories for many years to come so they can continue to be passed down.

The 95 Theses by Dr. Martin Luther

Comments Off on The 95 Theses by Dr. Martin Luther

Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences Commonly Known as The 95 Theses by Dr. Martin Luther

Out of love and concern for the truth, and with the object of eliciting it, the following heads will be the subject of a public discussion at Wittenberg under the presidency of the reverend father, Martin Luther, Augustinian, Master of Arts and Sacred Theology, and duly appointed Lecturer on these subjects in that place. He requests that whoever cannot be present personally to debate the matter orally will do so in absence in writing.

- When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said “Repent”, He called for the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.

- The word cannot be properly understood as referring to the sacrament of penance, i.e. confession and satisfaction, as administered by the clergy.

- Yet its meaning is not restricted to repentance in one’s heart; for such repentance is null unless it produces outward signs in various mortifications of the flesh.

- As long as hatred of self abides (i.e. true inward repentance) the penalty of sin abides, viz., until we enter the kingdom of heaven.

- The pope has neither the will nor the power to remit any penalties beyond those imposed either at his own discretion or by canon law.

- The pope himself cannot remit guilt, but only declare and confirm that it has been remitted by God; or, at most, he can remit it in cases reserved to his discretion. Except for these cases, the guilt remains untouched.

- God never remits guilt to anyone without, at the same time, making him humbly submissive to the priest, His representative.

- The penitential canons apply only to men who are still alive, and, according to the canons themselves, none applies to the dead.

- Accordingly, the Holy Spirit, acting in the person of the pope, manifests grace to us, by the fact that the papal regulations always cease to apply at death, or in any hard case.

- It is a wrongful act, due to ignorance, when priests retain the canonical penalties on the dead in purgatory.

- When canonical penalties were changed and made to apply to purgatory, surely it would seem that tares were sown while the bishops were asleep.

- In former days, the canonical penalties were imposed, not after, but before absolution was pronounced; and were intended to be tests of true contrition.

- Death puts an end to all the claims of the Church; even the dying are already dead to the canon laws, and are no longer bound by them.

- Defective piety or love in a dying person is necessarily accompanied by great fear, which is greatest where the piety or love is least.

- This fear or horror is sufficient in itself, whatever else might be said, to constitute the pain of purgatory, since it approaches very closely to the horror of despair.

- There seems to be the same difference between hell, purgatory, and heaven as between despair, uncertainty, and assurance.

- Of a truth, the pains of souls in purgatory ought to be abated, and charity ought to be proportionately increased.

- Moreover, it does not seem proved, on any grounds of reason or Scripture, that these souls are outside the state of merit, or unable to grow in grace.

- Nor does it seem proved to be always the case that they are certain and assured of salvation, even if we are very certain ourselves.

- Therefore the pope, in speaking of the plenary remission of all penalties, does not mean “all” in the strict sense, but only those imposed by himself.

- Hence those who preach indulgences are in error when they say that a man is absolved and saved from every penalty by the pope’s indulgences.

- Indeed, he cannot remit to souls in purgatory any penalty which canon law declares should be suffered in the present life.

- If plenary remission could be granted to anyone at all, it would be only in the cases of the most perfect, i.e. to very few.

- It must therefore be the case that the major part of the people are deceived by that indiscriminate and high-sounding promise of relief from penalty.

- The same power as the pope exercises in general over purgatory is exercised in particular by every single bishop in his bishopric and priest in his parish.

- The pope does excellently when he grants remission to the souls in purgatory on account of intercessions made on their behalf, and not by the power of the keys (which he cannot exercise for them).

- There is no divine authority for preaching that the soul flies out of the purgatory immediately the money clinks in the bottom of the chest.

- It is certainly possible that when the money clinks in the bottom of the chest avarice and greed increase; but when the church offers intercession, all depends in the will of God.

- Who knows whether all souls in purgatory wish to be redeemed in view of what is said of St. Severinus and St. Pascal? (Note: Paschal I, pope 817-24. The legend is that he and Severinus were willing to endure the pains of purgatory for the benefit of the faithful).

- No one is sure of the reality of his own contrition, much less of receiving plenary forgiveness.

- One who bona fide buys indulgence is a rare as a bona fide penitent man, i.e. very rare indeed.

- All those who believe themselves certain of their own salvation by means of letters of indulgence, will be eternally damned, together with their teachers.

- We should be most carefully on our guard against those who say that the papal indulgences are an inestimable divine gift, and that a man is reconciled to God by them.

- For the grace conveyed by these indulgences relates simply to the penalties of the sacramental “satisfactions” decreed merely by man.

- It is not in accordance with Christian doctrines to preach and teach that those who buy off souls, or purchase confessional licenses, have no need to repent of their own sins.

- Any Christian whatsoever, who is truly repentant, enjoys plenary remission from penalty and guilt, and this is given him without letters of indulgence.

- Any true Christian whatsoever, living or dead, participates in all the benefits of Christ and the Church; and this participation is granted to him by God without letters of indulgence.

- Yet the pope’s remission and dispensation are in no way to be despised, for, as already said, they proclaim the divine remission.

- It is very difficult, even for the most learned theologians, to extol to the people the great bounty contained in the indulgences, while, at the same time, praising contrition as a virtue.

- A truly contrite sinner seeks out, and loves to pay, the penalties of his sins; whereas the very multitude of indulgences dulls men’s consciences, and tends to make them hate the penalties.

- Papal indulgences should only be preached with caution, lest people gain a wrong understanding, and think that they are preferable to other good works: those of love.

- Christians should be taught that the pope does not at all intend that the purchase of indulgences should be understood as at all comparable with the works of mercy.

- Christians should be taught that one who gives to the poor, or lends to the needy, does a better action than if he purchases indulgences.

- Because, by works of love, love grows and a man becomes a better man; whereas, by indulgences, he does not become a better man, but only escapes certain penalties.

- Christians should be taught that he who sees a needy person, but passes him by although he gives money for indulgences, gains no benefit from the pope’s pardon, but only incurs the wrath of God.

- Christians should be taught that, unless they have more than they need, they are bound to retain what is only necessary for the upkeep of their home, and should in no way squander it on indulgences.

- Christians should be taught that they purchase indulgences voluntarily, and are not under obligation to do so.

- Christians should be taught that, in granting indulgences, the pope has more need, and more desire, for devout prayer on his own behalf than for ready money.

- Christians should be taught that the pope’s indulgences are useful only if one does not rely on them, but most harmful if one loses the fear of God through them.

- Christians should be taught that, if the pope knew the exactions of the indulgence-preachers, he would rather the church of St. Peter were reduced to ashes than be built with the skin, flesh, and bones of the sheep.

- Christians should be taught that the pope would be willing, as he ought if necessity should arise, to sell the church of St. Peter, and give, too, his own money to many of those from whom the pardon-merchants conjure money.

- It is vain to rely on salvation by letters of indulgence, even if the commissary, or indeed the pope himself, were to pledge his own soul for their validity.

- Those are enemies of Christ and the pope who forbid the word of God to be preached at all in some churches, in order that indulgences may be preached in others.

- The word of God suffers injury if, in the same sermon, an equal or longer time is devoted to indulgences than to that word.

- The pope cannot help taking the view that if indulgences (very small matters) are celebrated by one bell, one pageant, or one ceremony, the gospel (a very great matter) should be preached to the accompaniment of a hundred bells, a hundred processions, a hundred ceremonies.

- The treasures of the church, out of which the pope dispenses indulgences, are not sufficiently spoken of or known among the people of Christ.

- That these treasures are not temporal are clear from the fact that many of the merchants do not grant them freely, but only collect them.

- Nor are they the merits of Christ and the saints, because, even apart from the pope, these merits are always working grace in the inner man, and working the cross, death, and hell in the outer man.

- St. Laurence said that the poor were the treasures of the church, but he used the term in accordance with the custom of his own time.

- We do not speak rashly in saying that the treasures of the church are the keys of the church, and are bestowed by the merits of Christ.

- For it is clear that the power of the pope suffices, by itself, for the remission of penalties and reserved cases.

- The true treasure of the church is the Holy gospel of the glory and the grace of God.

- It is right to regard this treasure as most odious, for it makes the first to be the last.

- On the other hand, the treasure of indulgences is most acceptable, for it makes the last to be the first.

- Therefore the treasures of the gospel are nets which, in former times, they used to fish for men of wealth.

- The treasures of the indulgences are the nets which to-day they use to fish for the wealth of men.

- The indulgences, which the merchants extol as the greatest of favours, are seen to be, in fact, a favourite means for money-getting.

- Nevertheless, they are not to be compared with the grace of God and the compassion shown in the Cross.

- Bishops and curates, in duty bound, must receive the commissaries of the papal indulgences with all reverence.

- But they are under a much greater obligation to watch closely and attend carefully lest these men preach their own fancies instead of what the pope commissioned.

- Let him be anathema and accursed who denies the apostolic character of the indulgences.

- On the other hand, let him be blessed who is on his guard against the wantonness and license of the pardon-merchant’s words.

- In the same way, the pope rightly excommunicates those who make any plans to the detriment of the trade in indulgences.

- It is much more in keeping with his views to excommunicate those who use the pretext of indulgences to plot anything to the detriment of holy love and truth.

- It is foolish to think that papal indulgences have so much power that they can absolve a man even if he has done the impossible and violated the mother of God.

- We assert the contrary, and say that the pope’s pardons are not able to remove the least venial of sins as far as their guilt is concerned.

- When it is said that not even St. Peter, if he were now pope, could grant a greater grace, it is blasphemy against St. Peter and the pope.

- We assert the contrary, and say that he, and any pope whatever, possesses greater graces, viz., the gospel, spiritual powers, gifts of healing, etc., as is declared in I Corinthians 12 [:28].

- It is blasphemy to say that the insignia of the cross with the papal arms are of equal value to the cross on which Christ died.

- The bishops, curates, and theologians, who permit assertions of that kind to be made to the people without let or hindrance, will have to answer for it.

- This unbridled preaching of indulgences makes it difficult for learned men to guard the respect due to the pope against false accusations, or at least from the keen criticisms of the laity.

- They ask, e.g.: Why does not the pope liberate everyone from purgatory for the sake of love (a most holy thing) and because of the supreme necessity of their souls? This would be morally the best of all reasons. Meanwhile he redeems innumerable souls for money, a most perishable thing, with which to build St. Peter’s church, a very minor purpose.

- Again: Why should funeral and anniversary masses for the dead continue to be said? And why does not the pope repay, or permit to be repaid, the benefactions instituted for these purposes, since it is wrong to pray for those souls who are now redeemed?

- Again: Surely this is a new sort of compassion, on the part of God and the pope, when an impious man, an enemy of God, is allowed to pay money to redeem a devout soul, a friend of God; while yet that devout and beloved soul is not allowed to be redeemed without payment, for love’s sake, and just because of its need of redemption.

- Again: Why are the penitential canon laws, which in fact, if not in practice, have long been obsolete and dead in themselves,—why are they, to-day, still used in imposing fines in money, through the granting of indulgences, as if all the penitential canons were fully operative?

- Again: since the pope’s income to-day is larger than that of the wealthiest of wealthy men, why does he not build this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of indigent believers?

- Again: What does the pope remit or dispense to people who, by their perfect repentance, have a right to plenary remission or dispensation?

- Again: Surely a greater good could be done to the church if the pope were to bestow these remissions and dispensations, not once, as now, but a hundred times a day, for the benefit of any believer whatever.

- What the pope seeks by indulgences is not money, but rather the salvation of souls; why then does he suspend the letters and indulgences formerly conceded, and still as efficacious as ever?

- These questions are serious matters of conscience to the laity. To suppress them by force alone, and not to refute them by giving reasons, is to expose the church and the pope to the ridicule of their enemies, and to make Christian people unhappy.

- If therefore, indulgences were preached in accordance with the spirit and mind of the pope, all these difficulties would be easily overcome, and indeed, cease to exist.

- Away, then, with those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “Peace, peace,” where in there is no peace.

- Hail, hail to all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, “The cross, the cross,” where there is no cross.

- Christians should be exhorted to be zealous to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells.

- And let them thus be more confident of entering heaven through many tribulations rather than through a false assurance of peace.

2013 Revival of Study Bibles Reviews

- Read the Spirit Filled Life Bible Review

- Read the Fire Bible Review

- Read the Mission of God Study Bible Review

We are undertaking the task of comparing and reviewing a growing number of Study Bibles appearing on the book market recently in what appear to be a 21st century Revival of Study Bibles. We will be including some classical titles as well, but overall this study will have three parts dealing with three distinct types of Study Bibles namely: (1) Non-Pentecostal, (2) Pentecostal and (3) Prophecy Related. [read more]

Are Pentecostals offering Strange Fire?

Comments Off on Are Pentecostals offering Strange Fire?

Did tongues and the supernatural gifts of the Holy Spirit cease in the early church? John MacArthur says they did and that practicing them today is false worship—an abomination before God. Pneuma Review invites you to respond to these criticisms and to renew the biblical command to “desire spiritual gifts” (1 Cor 14:1).

Did tongues and the supernatural gifts of the Holy Spirit cease in the early church? John MacArthur says they did and that practicing them today is false worship—an abomination before God. Pneuma Review invites you to respond to these criticisms and to renew the biblical command to “desire spiritual gifts” (1 Cor 14:1).

We’ve been here before

In 1978, MacArthur wrote The Charismatics: A Doctrinal Perspective (Zondervan). Charismatic Chaos (Zondervan) was published in 1992. Dr. MacArthur launched his latest attacks against Pentecostal/charismatic beliefs with the Strange Fire conference (October 16-18, 2013), with speakers including Joni Eareckson-Tada and R. C. Sproul. His new book is Strange Fire: The Danger of Offending the Holy Spirit with Counterfeit Worship (Thomas Nelson), due out on November 12, 2013.

Not known for a conciliatory approach, John MacArthur’s inflammatory language is sure to polarize any attempt by Christians to discuss the gifts of the Spirit. We all agree that spiritual gifts can be and have been misused. There are significant doctrinal errors and poor theology being taught by some Christian leaders today. But are all Pentecostal/charismatics worshiping God falsely? Are they believing and teaching a counterfeit Gospel?

Invitation to participate

Pneuma Review has invited Pentecostal/charismatic scholars and Bible teachers from around the world to read and respond to MacArthur’s book. This is your opportunity to join the discussion about the continuation or cessation of the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

Use the Comment box below so that all of us may read your posts.

As we have this needed conversation

Please keep in mind the Pneuma Foundation’s (parent organization of Pneuma Review) principles for discussing controversial topics.

When presenting teachings over which there is disagreement in the body of Christ, the Pneuma Foundation will not make its position in a manner that alienates or ignores opposing views. It is better to follow the Biblical mandate of preferring others over ourselves (Phil. 2:3-4). The Foundation desires to present the differing viewpoints and promote dialogue, acknowledging that the goal of our instruction is love (1 Tim. 1:5).

Pentecostals too?

Is John MacArthur being as hard on Pentecostals as he is on charismatics? This brief video by MacArthur might make you think that he is more sympathetic towards classical Pentecostals. However, Dr. Michael Brown sent this note to us that he posted on his Facebook page:

For all those writing to me and claiming that Pastor MacArthur is reaching out to “faithful Pentecostals” in a conciliatory way, make no mistake about it: He renounces the entire charismatic movement as being in serious error and ends his book with a strong appeal to his reformed charismatic friends to completely renounce their beliefs in continuationism. It’s black and white, in his book, on my desk, no doubt about it.

John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, Reviewed by R. Loren Sandford

Strange Fire by John MacArthur is basically an attack on anything and everything related to the Charismatic Movement and the various movements descended from it, as if the whole of it were composed of one monolithic set of doctrines and practices that all of us espouse. It invalidates anything that smacks of the supernatural or of emotion freely expressed in God’s presence. MacArthur pours his vitriol – and I mean vitriol – through the filter of his own prejudices and theological presuppositions in a way that blinds him to the differences between the various movements within the charismatic stream and causes him to deny the existence of the majority of us who do not agree with or practice the abuses he objects to. In doing so he ignores or reinterprets, through very poor exegesis, the clear teaching of much of the Scripture as well. [Read more]

Strange Fire by John MacArthur is basically an attack on anything and everything related to the Charismatic Movement and the various movements descended from it, as if the whole of it were composed of one monolithic set of doctrines and practices that all of us espouse. It invalidates anything that smacks of the supernatural or of emotion freely expressed in God’s presence. MacArthur pours his vitriol – and I mean vitriol – through the filter of his own prejudices and theological presuppositions in a way that blinds him to the differences between the various movements within the charismatic stream and causes him to deny the existence of the majority of us who do not agree with or practice the abuses he objects to. In doing so he ignores or reinterprets, through very poor exegesis, the clear teaching of much of the Scripture as well. [Read more]

John MacArthur’s Strange Fire, Reviewed by Eddie L. Hyatt

![hyatt_1-140x205[1]](http://pneumareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/hyatt_1-140x2051.gif) As a life-long Pentecostal-Charismatic, I recommend that every Pentecostal-Charismatic leader read Strange Fire by John MacArthur. I say this because we need to see how the bizarre “spiritual” behavior and doctrinal extremes by some in our movement are viewed by those on the outside and are used to whitewash the entire movement. We have done a very poor job of addressing these problems from within, so I do not doubt that God has raised up a voice that is fundamentally opposed to our movement to address these extremes. If God could use a pagan Babylonian king to discipline his people Israel for their sins (Jeremiah 25:8-11), could he not use a merciless fundamentalist preacher to point out our shortcomings? [Read more]

As a life-long Pentecostal-Charismatic, I recommend that every Pentecostal-Charismatic leader read Strange Fire by John MacArthur. I say this because we need to see how the bizarre “spiritual” behavior and doctrinal extremes by some in our movement are viewed by those on the outside and are used to whitewash the entire movement. We have done a very poor job of addressing these problems from within, so I do not doubt that God has raised up a voice that is fundamentally opposed to our movement to address these extremes. If God could use a pagan Babylonian king to discipline his people Israel for their sins (Jeremiah 25:8-11), could he not use a merciless fundamentalist preacher to point out our shortcomings? [Read more]

MORE on the TOPIC:

Tim Challies: Lessons Learned at Strange Fire

Adrian Warnock: Strange Fire – A Charismatic Response to John MacArthur

ALEX MURASHKO: MacArthur Continues Case Against Charismatic Movement at ‘Strange Fire’

Alan Smith: SOME THOUGHTS IN RESPONSE TO THE STRANGE FIRE CONTROVERSY

SAMUEL RODRIGUEZ: John MacArthur Suffers From Spiritual, Cultural and Theological Myopia

Joela Barker: A Response to John MacArthur’s Strange Fire Conference

MICHAEL BROWN: A Final Appeal to Pastor MacArthur on the Eve of His ‘Strange Fire’ Conference

Sarah Pulliam Bailey: John MacArthur vs. Mark Driscoll: Megachurch pastors clash

Benjamin Robinson: Strange Fire? A Response to John MacArthur

CREDO HOUSE: WHY JOHN MACARTHUR MAY BE LOSING HIS VOICE

Keynote presentations from our speaking itinerary

Comments Off on Keynote presentations from our speaking itinerary

Keynote presentations from our speaking itinerary

Keynote presentations from our speaking itinerary

2013 Video Bible Project at Logos BibleTech Conference

2012 Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals at Society for Pentecostal Studies at Seattle Pacific University

2011 The (un)Forgotten: Story of Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s Children at Society for Pentecostal Studies at Memphis Theological Seminary

2011 Broadcast Your Church at Leadership Development Institute

2010 Using Computer Technologies in the Making of the New Bulgarian Translation of the Bible at Logos BibleTech Conference

2010 The Untold Story of the Life and Ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev at Society for Pentecostal Studies at North-Central University

2009 Underground Web Ministry within the Postcommunist Matrix at Logos BibleTech Conference

2009 Ministry on the Internet at Leadership Development Institute

2007 Bulgarian American Congregations: Cultural, Economic and Leadership Dimensions at Society for Pentecostal Studies

2006 The Story of the Bulgarian Bible at Evangelical Theological Society (video)

2006 Introductory Chaplaincy Training Course at the Bulgarian Chaplaincy Association Quarterly Meeting

2005 Internal Motivation at the Bulgarian Chaplaincy Association Quarterly Meeting

2005 Bulgarian Churches in North America at the Bulgarian Evangelical Alliance Annual Meeting

2004 Postcommunist Believers in a Postmodern World at the 4th Annual Lilly Fellows National Research Conference

Key Publications:

Spring 2013 Bulgarian New Testament (Special Study Edition for Bulgarian Churches and Diasporas Abroad), Spasen Publishers

2012 The Life and Ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev (with the (un)Forgotten:Story of the Voronaev Children)

2012 Bulgarian Churches in North America: Analytical Overview and Church Planting Proposal for Bulgarian American Congregations Considering Cultural, Economical and Leadership Dimensions, Spasen Publishers

2011 The Case of Underground Chaplaincy in Bulgaria (A Case Study for NATO’s Manfred Wormer Foundation)

July, 2007-present, Letters from Bulgaria: A Series on Bulgarian Pentecostal Heritage in Pentecostal Evangel

Spring 2006, When East Met West in East-West Church & Ministry Report

July 2006, Roberts College in Pro & Anti Newspaper

Fall 2005, Postcommunist Believers in a Postmodern World in East-West Church & Ministry Report

April 2005-2009, Bulgarian Protestant History Series in Evangelical Newspaper

April 2005-2010, About the Bible Series in Evangelical Newspaper (Published in one volume by Spasen Publishers)

March 2002, Bible Studies on the Church of God Declaration of Faith, Spasen Publishers

May 2001, Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved, Spasen Publishers

September 2000, To Harvard and Back a Hundred Years Later (A Biographical Sketch of Stoyan K. Vatralsky)

January 1994, “Going Up”, Christian News, Newspaper of the BulgarianChurch of God

1998-2003, Commentary on the Four Gospels for the Bulgarian On-Line Bible [http://www.bibliata.com]

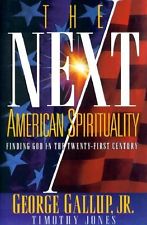

The Next American Spirituality

Gallup and Jones examine a 24 hour observation of how America does Biblical spirituality, using the gathered data to analyze its shift and direction. According to their survey, the marks of the next American spirituality are:

Gallup and Jones examine a 24 hour observation of how America does Biblical spirituality, using the gathered data to analyze its shift and direction. According to their survey, the marks of the next American spirituality are:

1. Bull-market spirituality

2. Religion of me and thee

3. Hunger for experience

4. Search of roots amid the relativism

5. Quest for community

In my present context of ministry all of the above signs are evident to extend. This is due on hand to the constant shift in the cultural paradigm, as well as the obvious shift in the identity and practices of the Christian church in the postmodern context. In same aspects, it almost seems like instead of being the model, the church is following a model, which not only changes the churches identity but interferes with its original evangelistic goal and global mission. It is also true that in some of the cases, where the church is expected to give answer to a dilemma or an issue it searches for the answer from the surrounding culture, economy and practices, thus underestimating its own spiritual abilities, gifts and resources.

Bull-market spirituality

a. Source: Rapid development of 20th century economy and its direct implication in the present consumerism culture.

b. Positive results on the church: The church observes and implements market management to improve its existence as a serving community.

c. Negative results on the church: Church members, expect to only receive from the church without giving to the church. The church focuses more on its management than on its mission.

d. Effect on the secular community: Occasional visitors and secular observers expect even better service from the church, using its inability to satisfy their caprices as an excuse for a personal lifestyle.

e. Effect on the discipleship process: Since the church has become a market for one’s spirituality traditional discipleship is hindering the model since it brings definite requirements and commitments.

Religion of me and thee

a. Source: Consumerism culture has enviably led to a self-centered society where everything must occur in subjection to the self.

b. Positive results on the church: The church focuses on its internal dilemmas and problems, investing in their solutions through further development and growth.

c. Negative results on the church: The church operates on insufficient time when the care for the community “outside the gate” is concerned, thus becoming a self-centered, centralized community.

d. Effect on the secular community: Naturally the existence of the community is distanced from the mission of the church.

e. Effect on the discipleship process: The discipleship process struggles to exist in such church context, since by its very nature it is a self-development process that purposes to enrich the community more than the self.

Hunger for experience

a. Source: Postmodernism denies all modern developments and discoveries as existentially important claiming the need for a newer, fresher and more powerful experience.

b. Positive results on the church: The church has an opportunity to become a beacon to the community and to offer the true existential experience – Biblical salvation.

c. Negative results on the church: Because there is a lack of understanding that the Pentecostal experience is what the postmodern world is looking for, the church misses the opportunity to fulfill its role.

d. Effect on the secular community: The secular community has an opportunity to equalize its search with the Christian experience.

e. Effect on the discipleship process: There is a definite search for experience; however, it is not rooted in theology.

Search of roots amid the relativism

a. Source: Rapid development of 20th century modernism has led to a postmodern questioning and search for newer experience and identity.

b. Positive results on the church: The church has an opportunity to present its spiritual roots and heritage as an identity source for the searching.

c. Negative results on the church: The church is unable to offer its spiritual roots and heritage since it has neither lost them nor has lost its ability to manifest them. Thus, roots are claimed but not practiced.

d. Effect on the secular community: The secular community struggles with the dilemma of obtaining spirituality and identity without understating its roots and history.

e. Effect on the discipleship process: The discipleship process is effective only when rooted in the spiritual heritage of the Christian church.

Quest for community

a. Source: The postmodern questioning of values and loss of identity results in a search for belonginess.

b. Positive results on the church: Naturally, the church can offer community to the ones in search for belonginess.

c. Negative results on the church: The church is unable to offer community, since it has lost its since and structure of being a Biblical community.

d. Effect on the secular community: The secular community can become part of the ecclesial community thus obtaining its identity and values.

e. Effect on the discipleship process: Discipleship reaches its ultimate results.

The Next Christendom

Philip Jenkins recent work, The Next Christendom, focuses on the growth of Christianity outside of the Western world in the twentieth century. The book explores the emergence of powerful and dynamic Christian movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The author emphasizes that by 2050 only about one-fifth of the world’s three billion Christians will be non-Hispanic whites and concludes that the rise of Christianity in the Third World will exacerbate the confrontations with Islam.

Jenkins draws his conclusions on the clash of civilizations theory advanced by Samuel Huntington. According to this, the future world conflicts will be between cultures with radically different religious views. One of them is the clash between the Christian and Islamic civilizations. Therefore, the author goes into a great detail on the description of cultural (ethnic and religious) war between Christianity and Islam.

In chapter one Christianity and Islam will grow both by birth and conversion and that by 2050 (again at least nominally), Christians will likely still outnumber Muslims (pp. 5-6). This chapter introduces the three main arguments of the book:

1. Christianity will be dominated by churches in the Southern hemisphere

2. Southern Christianity is conservative, fundamentalist and traditional

3. Understanding Christianity requires understanding Southern Christianity

In chapter six Jenkins identifies the common growth characteristics of such churches as the Brazilian-based Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, or The Full Gospel Central Church in South Korea, or the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ on Earth of the Prophet Simon Kimbangu in Congo. The text observes their dynamics and growth in the midst of difficult and oppressive circumstances. These characteristics are summarized in the following list:

1. Emphasis on the Holy Spirit

2. Charismatic leadership

3. Definite doctrine/teaching

4. Social direction toward identity, community, and eternal hope.

Many of these new churches/movements follow a conservative theological trajectory with a close and even literalistic reading of the Bible. Jenkins sees a definite connection between this non-Western churches and some new churches and in the South that are fundamentalist and charismatic by nature and theologically conservative, with a powerful belief in the spiritual dimension, in visions and in spiritual healing (p. 137).

He further claims, that the real battle for religious strife in the near future will be the armed conflicts between Christians and Muslims in Africa and Asia. One of the possible scenarios of the future world is that the Northern population will decrease tremendously, still supporting the values and ideology of liberal Christianity and Judaism. There will be also a future confrontation with the the poorer and more numerous global (pp. 160—161). In this same chapter, on page 118, Jenkins writes, “There is now talk that the Virgin [Mary] might be proclaimed a mediator and co-Savior figure, comparable to Jesus himself, even a fourth member of the Trinity.” To me this was quite a misunderstanding point.

In chapter eight (“The Next Crusade”) the author discusses inter-religious relations, particularly between Christianity and Islam.

Chapter ten (“Seeing Christianity Again for the First Time”) declares that the considering a possible is descriptive of the present day (p. 218).

To present Pentecostalism, as an answer for Christianity and church praxis in the beginning of postmodernism is not a new strategy. A similar study has been already introduced by Dr, Harvey Cox in his book “Fire from Heaven.” His work observes primarily Latin America and suggests that Pentecostalism is indeed that wing of Christianity that will serve for its postmodern interpretation. The Christian churches have indeed been successful in the South. The reason for this is that they have become missions for social needs. Countries with great economic and demographic difficulties have experienced Pentecostalism as the answer for these social, economical and political earthquakes.

Moves of Christian culture such like the one described by Jenkins are not new either. Christ has commission the church to witness of his resurrection in Jerusalem, Galilee, Samaria, and to the outermost parts of the earth. Then, as the church reaches Europe, the New Testament gives a clear movement toward North West – Rome and Spain. Moves toward the North have been present in the evangelization of Eastern Europe during the Byzantium period, as well as later North Eastern moves of Christianity toward Russia. The move toward the West can be placed along with the discovery of the New World. In this trend of thought, if must claim a southern move of Christianity, then places like Australia and New Zealand must be the main target of such mission. As an overall “The Next Christendom” is informative and rich of factual support. It presents unique information. Although its claims are offered with caution, foretelling world’s history was not its best side.

Maxwell Leadership Bible

The Maxwell Leadership Bible has drawn lots of attention especially with the publication of John Maxwell’s new bestseller “Sometimes you win, sometimes you learn,” which deconstructs the winning model of church leadership on a totally different level. We’ve used his study Bible through the years especially in cases of young ministers’ training and mentorship.

Instead of a page by page annotation, the Maxwell Bible setup contains inline articles and discussions on various leadership issues within the text. Over 100 biographical profiles of Biblical leaders and short articles are combined with the philosophy behind two other bestsellers on leadership by the author: “The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership” and “The 21 Indispensible Qualities of a Leader”

One of our initial comparison passages (Numbers ch.6 and Jeremiah ch.18) is commented, although Numb. 6 does have an article on the Nazarite vow within the Law of Sacrifice (qt. “Give up to go up”). Jeremiah 18, however, contains a great note on “teachability.” The annotation of v. 18 is simple, but strong: “To keep leading, keep learning!”

The Maxwell Bible is not doctrinally organized per se. Therefore, there’s not much on eschatology and particularly Rapture and Tribulation. Nevertheless, the lessons from the 7 Churches of Revelation are abundantly annotated and worthy to be read privately or taught in a classroom setting, but most of all taken literary and applied to today’s ecclesial reality.

This work is also not Pentecostal in particular, as it addresses church leadership in a general Biblical sense. There’s no particular reference to the Trinity, however Acts 2 comments on the magnetic power received by the apostles at Pentecost and in 1 Corinthians 14, the Spirit is called “Broker of gifts.” Instead of a concordance at the end of the Bible, there are several indexes containing leadership laws, qualities, issues and a complete list of profiles of Bible heroes who encompass the law of leadership.

![30551617[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/305516171-150x150.jpg)

![38664980[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/386649801-150x150.jpg)

![46316653[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/463166531-150x150.jpg)

![6329403_orig[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/6329403_orig1-e1399505508850.jpg)