The Bulgarian Evangelical Believer and Communistic Consequences

The collapse of Bulgaria’s previous social order, communism, left the country with a moral and ideological void that was quickly filled with crime and corruption. A culture originally shaped by communism currently is influenced by capitalism and democracy. Post communist mentality with definite Balkan characteristics rules the country as a whole. This mentality holds captive nearly every progressive thought and idea. In the post communist context, the atheistic mind is a given and even when an individual experiences a genuine need for spirituality, in most cases he or she has no religious root to which to return other than Orthodoxy. This lack of alternative or spiritual choice produces a pessimistic morale.

The collapse of Bulgaria’s previous social order, communism, left the country with a moral and ideological void that was quickly filled with crime and corruption. A culture originally shaped by communism currently is influenced by capitalism and democracy. Post communist mentality with definite Balkan characteristics rules the country as a whole. This mentality holds captive nearly every progressive thought and idea. In the post communist context, the atheistic mind is a given and even when an individual experiences a genuine need for spirituality, in most cases he or she has no religious root to which to return other than Orthodoxy. This lack of alternative or spiritual choice produces a pessimistic morale.

From an environment of uncertainty and hopelessness, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer turns to the continuity of faith in the Almighty Redeemer. Pentecostalism as practical Christianity gives a sense of internal motivation to the discouraged. In a society that is limited in conduciveness for progression of thought or self actualization, one finds refuge in the promises of Christianity. It becomes a certainty which can be relied upon. Historically, having undergone severe persecution, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer is one who possesses great devotion to his or her belief. Having to defend the faith fosters a deep sense of appreciation and in an impoverished country, faith becomes all some have. Christ becomes the only one to whom to turn for provision. In the midst of this complete dependence is where miracles occur. Furthermore, it is in the midst of miracles where the skepticism which is prominent in post communist Bulgaria is broken. When those who believe are healed from cancer and even raised from the dead, there is no room for disbelief or low self-esteem. Surrounded with insecurity and uncertainty, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer finds great hope and comfort in the fact that God holds the future in His hands. Christianity is a reality that is certain.

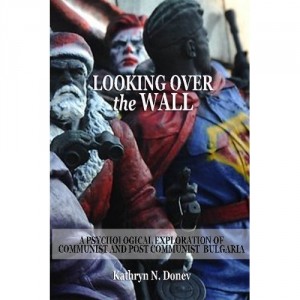

Excepts taken from “LOOKING OVER the WALL”

A Psychological Exploration of Communist and Post Communist Bulgaria

Copyright © April 12, 2012 by Kathryn N. Donev

© 2012, Spasen Publishers, a division of www.cupandcross.com

RELATED ARTICLES:

[ ] Obama, Marxism and Pentecostal Identity

[ ] A Psychological Exploration of Communist and Post Communist Bulgaria

[ ] Insight into Communist Agent Techniques in Bulgaria

[ ] The Bulgarian Evangelical Believer and Communistic Consequences

[ ] Distinct Historical Memories of the Bulgarian Mindset

[ ] National Identity and Collective Consciousness of the Bulgarian Community

Financial Times: Bulgaria needs stability before uncertainty

A caretaker government in Sofia will do its utmost to steady the tiller before May’s snap elections, following several weeks of street protests that toppled the previous administration and plunged Bulgaria into political uncertainty. But what happens after the poll is anybody’s guess. Many in Sofia’s political elite seem reluctant to grasp the poisoned chalice of leadership and their capacity to satisfy the demands of a restive and inchoate popular movement is limited.

On Wednesday, President Rosen Plevneliev ended weeks of speculation by naming Marin Raykov, Bulgaria’s ambassador to France, as caretaker prime minister until the May 12 elections. Raykov is a career diplomat and was deputy foreign minister under a right-of-centre government between 1998 and 2001 and again in 2009-2010 under Boyko Borisov, whose resignation as prime minister last month led to the political void which Raykov must temporarily fill. Raykov also served as an ambassador and a foreign policy chief under the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), the main opposition force. The new premier will be backed by a cabinet including three deputy prime ministers – all women – Bulgaria’s first female interior minister and a selection of other “experts” drawn from various parts of national life, particularly academia. There are also some promotions from within Borisov’s GERB party.

Bulgarian journalists have been quick to pick up on Raykov’s family background. His father, Rayko Nikolov, was a senior ambassador in the Communist era, including to the UN, Yugoslavia and France. Nikolov’s reported close links to the intelligence services come as a surprise to no-one. But of more interest is the allegation, made by the French press some years ago, that he was responsible for recruiting French politicians to work for the Soviet Union, including Charles Hernu, who went on to be defence minister in the 1980s.

Raykov’s political career on the “reformist” right but with roots among the Communist nomenklatura have led to suspicions that he is what Bulgarians gnomically call a “hidden lemon” – someone who is not what they appear to be. But Raykov’s diplomatic record suggests that he is robustly on the pro-European, rather than pro-Kremlin, side of Bulgarian politics, according Ivo Indzhev, a well-regarded Bulgarian blogger. And after all, one can’t choose one’s parents.

Dimitar Bechev, head of the Sofia office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank, says Raykov is a sound choice. “This government won’t do much beyond organise the elections,” he says. “Raykov is solid – linked to the 1990s right, but with enough credibility with all parties. He brings predictability and reassurance, as well as credibility for outsiders. He is aware of European policy issues and shows that Bulgaria will play by the rules.”

With the temporary administration in place, attention shifts to the election and what is likely to be a confused aftermath. Polls suggest GERB and the BSP are level pegging, with the largely Muslim-backed DPS and Bulgaria for the Citizens, led by former European Commissioner Meglena Kuneva, also likely to make it to the next parliament. Confusingly, BSP leader and ex-prime minister Sergey Stanishev has said he will not be premier again, while Kuneva has indicated that her party will not join a coalition.

Anthony Georgieff, a Bulgarian journalist and a vocal critic of Borisov, says the most likely scenarios as the mainstream opposition backs away from government are a discredited GERB being returned to power, considerably weakened, or the strengthening of hardline left- and right-wing forces unpalatable to Bulgaria’s EU partners. The far-right party Ataka, until recently seen as on the wane, seems to be recovering, and ultranationalists have been a significant presence at many demonstrations, along with well as anti-capitalist malcontents.

“Bulgaria’s moral crisis is reflected in the mainstream politicians refusing to take part in any coalition government of the future, and in the general public voting with their feet,” he says. Bechev is more upbeat, saying that Stanishev and Kuneva’s statements should be “taken with a pinch of salt”. He outlines a number of more moderate outcomes, including a grand coalition with GERB but without Borisov, and a BSP-DPS partnership, possibly bringing in Bulgaria for the Citizens, not dissimilar to the government from 2005 to 2009.

Whether any of these permutations will have the political will, economic resources and administrative capacity to address the demands of the street protesters – and the many Bulgarians at home who have lost faith in the political elite’s ability to deliver real change – is questionable. Demonstrations that started over power prices now encompass grievances such as corruption, authoritarianism, government links to organised crime, and privatisation. Most fundamentally, they may be about low incomes and lack of prospects in the EU’s poorest country – something that Raykov has said that he will look to address, within his capabilities. But with the eurozone, Bulgaria’s main trading and investment partner, still in crisis, and the legacy of years of maladministration at home, immediate change for the better seems unlikely.

“Unlike other crises Bulgaria has had since it shook off Communism in 1989, the current one has no easy answers because there is little if anything to look forward to, Bulgaria now being a full member of the EU and NATO,” says Georgieff. The death by self-immolation of three demonstrators since protests began certainly indicates the desperation that many Bulgarians feel. But some are hopeful that the street movement can put pressure on the next government to deliver the transparency and accountability that has been lacking from its predecessors.

NY Times: Bulgaria’s Unholy Alliances

By MATTHEW BRUNWASSER

SOFIA — His enthronement as patriarch of Bulgaria, spiritual leader of millions of Orthodox believers here, was supposed to stir pride and moral togetherness in an impoverished country confronting a vacuum in political leadership and widespread economic pain. Instead, the installation of His Holiness Neofit last month, in a ceremony replete with byzantine splendor, served as one more reminder that Bulgaria had never really thrown off the inheritance of 40 years of rigid Communist rule and all the duplicitous dealings that went with it.

Bulgaria has suffered fresh turmoil since mid-February, when nationwide protests erupted over a rise in power prices. The national government resigned in what it said was a bid to avert more bloodshed. But this week, the country went into nationwide mourning over the death of one protester, Plamen Goranov, 36, who set himself on fire in front of a public building in his hometown, Varna.

The church has played no part in calming its troubled nation. Like 11 of the 14 metropolitan bishops who make up the ruling synod of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Neofit was revealed to have a file documenting or implying cooperation with the powerful secret police under Communism. Proof of collaboration — for which the church has never apologized — was expected, but the number of bishops implicated when a state commission opened the files on church leaders in January 2012 “was beyond all expectations,” noted Momchil Metodiev, a historian who has researched the church in the Communist era.

By comparison with the 30-volume record involving Simeon, the Bulgarian Church’s current metropolitan for Western Europe, Neofit’s 16-page file was slender. While the file contained only a proposal by the authorities to recruit him as an agent and a negative assessment of his suitability for State Security work, the revelations raised tantalizing questions about whether more incriminating documents had been removed. That such questions linger, more than 20 years after Communism, illustrates Bulgarians’ messy relationship to that past.

One day after the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, the Communist dictator Todor Zhivkov, who had been in power since 1954, was deposed, not by popular uprising but in a palace coup. The politics behind the act remained murky, meaning that his removal is still a matter of dispute. Few Bulgarians can say the word “democracy” without irony or bitterness, because while they gained freedom and their country has now joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union, it has remained poor and underdeveloped, with the riches most dreamed of under capitalism reserved for the lucky, often criminally connected, few. And although State Security officially disbanded, its officials have retained a hold, contributing to the lack of clarity or debate about the past.

Many former agents went into private business and recruited wrestlers for muscle. Their networks, often criminal, gradually took over much of Bulgaria’s legitimate economy, helping to make Bulgaria notoriously corrupt, said Philip Gounev, a corruption expert at the Center for the Study of Democracy in Sofia. Similarly, the church has not faced up to its past. “Just as people say that our country is in ‘state capture’ by criminals and oligarchs who have taken control of the state, the church is in a state of ‘state capture’ by metropolitans associated with the state security police,” Mr. Gounev said.

The church counters that it is, for instance, planning to canonize martyrs from the Communist era over the next two years, making saints of those found to have died or been imprisoned for the faith among the thousands of believers who were persecuted. “We can expect to close the page of our Communist heritage by this very symbolic act,” said Desislava Panayotova, from the cultural department of the Holy Synod.

But it seems that it will take more than canonizations to restore the church’s position as a moral beacon in an increasingly secular society. After the state, the church is the second-largest landowner in the country, making it an attractive target for criminal groups. With its weak management and opaque institutions — the church does not, for instance, have a designated media spokesperson — observers say the church has remained aloof from any state efforts to clean up corruption. While many historic churches and monasteries crumble from neglect, the Bulgarian news media relay a stream of shocking stories about church officials’ luxury cars, expensive watches, shady land deals and ties to questionable businessmen.

The Stara Zagora metropolitan, Galaktion, a close rival to Neofit in the recent patriarchal election, bestowed an honorific church title on a wealthy sponsor, Slavi Binev, a former taekwando champion and owner of a security firm who is now also a member of the European Parliament. Mr. Binev was described in a 2005 WikiLeaks cable from the U.S. Embassy in Sofia as heading a group whose “criminal activities include prostitution, narcotics, and trafficking stolen automobiles.” In response, Mr. Binev told a Bulgarian newspaper that he was not perturbed to be on a list of people who were “the blossom” of Bulgarian business in the transition from Communism.

The metropolitan of Plovdiv, Nikolai, bestowed the same church title on Petar Mandzhukov, an international arms dealer, and later announced that he planned to sell his Rolex watch to pay the unpaid electricity bill for a church in his diocese, apparently hoping to quell public anger both at church riches and at the rising price of electricity that helped spark the recent protests. The church has also been accused of paying priests in cash to avoid social welfare payments and taxes.

One huge challenge is healing the post-Communist schism of 1992, when priests who said they had opposed Communism formed their own synod. Ugly disputes over church properties resulted, including physical fights. The police were called in during one particularly fierce battle over the church candle factory, a major source of income. Mr. Metodiev, the historian, who describes himself as “anti-Communist,” made a surprising discovery during research in the secret police files. “The leaders of the schismatic synod were in fact the closest allies of the Communist Party in the synod during the Communist period,” he said.

One bishop notorious for implementing State Security orders — Kalinik, the metropolitan of Vratsa — remains on the church synod today. Mr. Metodiev asserts that those with ties to State Security, particularly those recruited as young informers in the 1970s and 1980s, are now powerful, making the synod in fact more staffed by secret police than any other, including during Communism itself. “The very idea of meritocracy failed,” Mr. Metodiev said. “People are now accustomed to developing their careers due to connections. This is one of the most damaging long-term results of the power of the State Security.”

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio Named New POPE

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been elected by his peers as the new pope, becoming the first pontiff from the Americas. He has chosen to be known as Pope Francis I.

Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been elected by his peers as the new pope, becoming the first pontiff from the Americas. He has chosen to be known as Pope Francis I.

The 76-year-old has spent nearly his entire career at home in Argentina, overseeing churches and shoe-leather priests.

Francis, the archbishop of Buenos Aires, reportedly got the second-most votes from the 115 cardinals after Joseph Ratzinger in the 2005 papal election, and he has long specialized in the kind of pastoral work that some say is an essential skill for the next pope.

In a lifetime of teaching and leading priests in Latin America, which has the largest share of the world’s Catholics, Francis has shown a keen political sensibility as well as the kind of self-effacing humility that fellow cardinals value highly.

He is also known for modernizing an Argentine church that had been among the most conservative in Latin America. Like other Jesuit intellectuals, Bergoglio has focused on social outreach. Catholics are still buzzing over his speech last year accusing fellow church officials of hypocrisy for forgetting that Jesus Christ bathed lepers and ate with prostitutes. Bergoglio has slowed a bit with age and is feeling the effects of having a lung removed due to infection when he was a teenager.

In taking the name Francis, he drew connections to the 13th century St. Francis of Assisi, who saw his calling as trying to rebuild the church in a time of turmoil. It also evokes images of Francis Xavier, one of the 16th century founders of the Jesuit order that is known for its scholarship and outreach. Francis, the son of middle-class Italian immigrants, is known as a humble man who denied himself the luxuries that previous Buenos Aires cardinals enjoyed. Bergoglio often rode the bus to work, cooked his own meals and regularly visited the slums that ring Argentina’s capital. He came close to becoming pope last time, reportedly gaining the second-highest vote total in several rounds of voting before he bowed out of the running in the conclave that elected Pope Benedict XVI. Groups of supporters waved Argentine flags in St. Peter’s Square as Francis, wearing simple white robes, made his first public appearance as pope.

Chants of “Long live the pope!” arose from the throngs of faithful, many with tears in their eyes. Crowds went wild as the Vatican and Italian military bands marched through the square and up the steps of the basilica, followed by Swiss Guards in silver helmets and full regalia. Francis appeared on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica after the vote. Earlier in the same place, a church official announced “Habemus Papum” — “We have a pope” — and gave Bergoglio’s name in Latin.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, good evening,” he said before making a reference to his roots in Latin America, which accounts for about 40 percent of the world’s Roman Catholics.

Francis asked for prayers for himself, and for retired Pope Benedict XVI, whose surprising resignation paved the way for the conclave that brought the first Jesuit to the papacy.

“Brothers and sisters, good evening,” Francis said to wild cheers in his first public remarks as pontiff. “You know that the work of the conclave is to give a bishop to Rome. It seems as if my brother cardinals went to find him from the end of the earth. Thank you for the welcome.”

Bergoglio has shown a keen political sensibility as well as the kind of self-effacing humility that fellow cardinals value highly, according to his official biographer, Sergio Rubin. He showed that humility on Wednesday, saying that before he blessed the crowd he wanted their prayers for him and bowed his head.

“Good night, and have a good rest,” he said before going back into the palace.

White smoke billowed from the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel earlier Wednesday, indicating the cardinals selected Francis after two days of voting after Benedict XVI stunned the Catholic world last month by becoming the first pope in 600 years to resign. Crowds packing St. Peter’s Square were seen waving flags and were cheering the announcement as bells were ringing. Prior to being announced as the new pope by French Cardinal Protodeacon Jean-Louis Pierre Tauran, Francis would have been asked inside St. Peter’s Basilica “Do you accept your canonical election as Supreme Pontiff?”

After giving his approval, Francis was then asked which name he would like to be called, and other cardinals would have approached him to make acts of homage and obedience. Francis also had to be fitted into new robes, and all the cardinals took time for prayer and reflection. Elected on the fifth ballot, Francis was chosen in one of the fastest conclaves in years, remarkable given there was no clear front-runner going into the vote and that the church had been in turmoil following the upheaval unleashed by Pope Benedict XVI’s surprise resignation.

The conclave also played out against revelations of mismanagement, petty bickering, infighting and corruption in the Holy See bureaucracy. Those revelations, exposed by the leaks of papal documents last year, had divided the College of Cardinals into camps seeking a radical reform of the Holy See’s governance and those defending the status quo.

The Vatican spokesman, the Rev. Federico Lombardi said it was a “good hypothesis” that Francis would be installed next Tuesday, on the feast of St. Joseph, patron saint of the universal church. The installation Mass is attended by heads of state from around the world, requiring at least a few days’ notice. Benedict XVI would not attend, he said.

In Washington, President Barack Obama offered warm wishes to newly elected Pope Francis I. Obama said the selection of the first pope from the Americas speaks to the strength and vitality of the region. He said millions of Hispanic Americans join him in praying for the new pope. The Vatican earlier on Wednesday divulged the secret recipe used: potassium perchlorate, anthracene, which is a derivative of coal tar, and sulfur for the black smoke; potassium chlorate, lactose and a pine resin for the white smoke.

Thousands of people braved a chilly rain on Wednesday morning to watch the 6-foot-high copper chimney on the chapel roof for the smoke signals telling them whether the cardinals had settled on a choice. Nuns recited the rosary, while children splashed in puddles. The chemicals were contained in five units of a cartridge that is placed inside the stove of the Sistine Chapel. When activated, the five blocks ignite one after another for about a minute apiece, creating the steady stream of smoke that accompanies the natural smoke from the burned ballot papers. Despite the great plumes of white and black smoke that poured out of the chimney, neither the Sistine frescoes nor the cardinals inside the chapel suffered any smoke damage, Lombardi said.

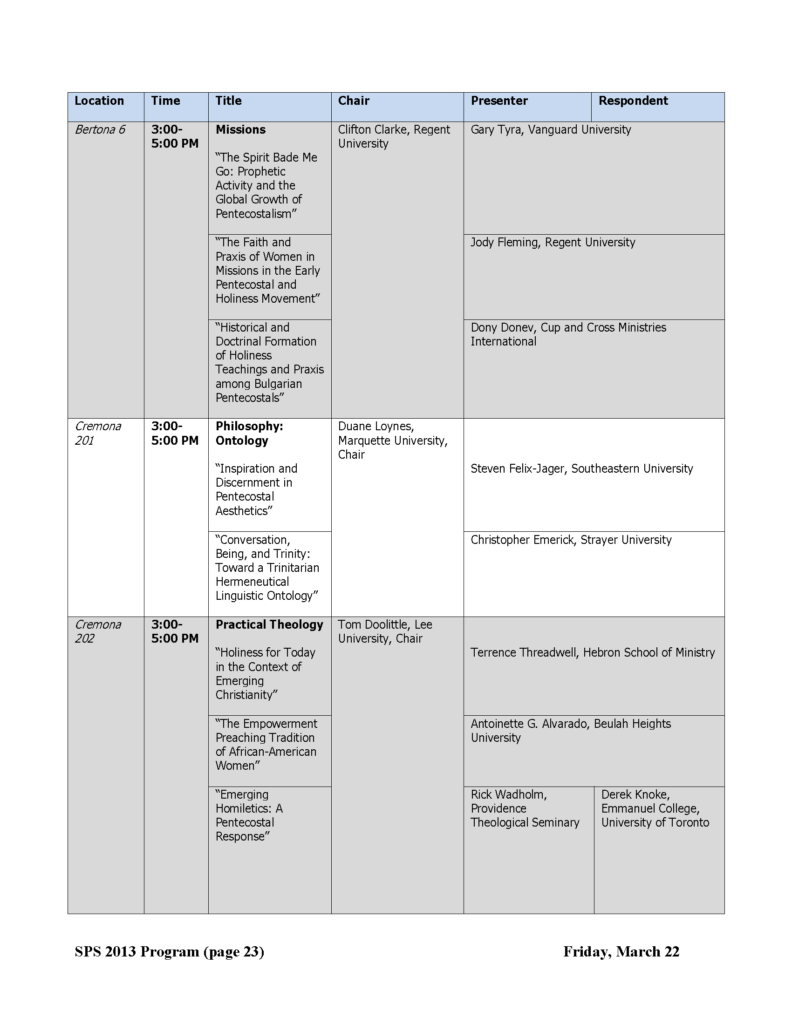

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle Pacific University on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

March 10, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under News, Publication, Research

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

Leadership Crisis in Bulgaria

As Bulgaria is celebrating its Liberation Day on March 3rd, protests are still going on in most major Bulgarian cities. Neither the resignation of the Prime Minister and the leading party from the government amidst deepening economics crises, nor the appointment of a new patriarch to the Orthodox Church was able to calm the crowds who have been out in the streets for weeks now. General government elections are scheduled for May 12, 2013 while the President is working with parliament on forming an interim government.

As Bulgaria is celebrating its Liberation Day on March 3rd, protests are still going on in most major Bulgarian cities. Neither the resignation of the Prime Minister and the leading party from the government amidst deepening economics crises, nor the appointment of a new patriarch to the Orthodox Church was able to calm the crowds who have been out in the streets for weeks now. General government elections are scheduled for May 12, 2013 while the President is working with parliament on forming an interim government.

After the last election some four years ago, political analysts working closely with our ministerial team warned that if newly elected government continues to use the same local level (city, municipality) political paradigms to run the country as a member of the European Union, crises will be inevitable. This was obvious even to the social concern grassroots including our chaplaincy program and para-church ministries.

Two years later, as half of the parliamentarian term has passed, we further advised in “Election’s Perspectives for Bulgaria” that as Bulgaria’s Prime Minister elect did not take the much expected place as a presidential candidate, his political strategy has been strongly criticized by his opponents as inadequate and insufficient to answer Bulgaria’s current crises. Amidst the global economic collapse, it was reasonable to suggest that similar socioeconomic shifts will not be long before appearing in Bulgaria.

The year 2013 began with a political distress in one of Bulgaria’s ethnic parties through a “backstage” attack against their soon to resign leader. The opposition responded immediately releasing a secret dossier code named “Buddha” revealing the Prime Minister working as a secret agent for the communist government police. His resignation, along with the resignation of the whole Cabinet, followed less than two weeks later as protests swept the streets of Bulgaria in the month with lowest temperatures, highest electric bills and of course highest rate of the government disapproval.

Meanwhile, after almost entering Bulgaria’s parliament in 1997, the Bulgarian Christian Coalition, traditionally representing the Protestants in the country, remains on the borderline of any political existence. Bulgarian evangelicals were never able to reach their political legacy again, although the new Bulgarian census showed over 25% increase of evangelical population in Bulgaria to some 65,000 people strong. The alternative party, Christian Democratic Forum has showed no political activity since it was established a decade later and quickly defeated by having less than 1,000 votes nationwide. The Bulgarian Christian Coalition has also chosen not to run in the upcoming elections.

Repost: Ministry NOT for Sale

My son, if sinners entice thee, consent thou not (Proverbs 1:10)

My son, if sinners entice thee, consent thou not (Proverbs 1:10)

Several years ago, while employed with a certain organization, we faced the dilemma to choose between what was morally right and what was financially secure. Regardless of the jeopardy of this predicament, we were able to make the right decision, preserving our integrity and disallowing financial pressure to dictate our moral choices. Soon thereafter, we initiated a healing process which dealt with the internal wounds, restored the lost trust and attempted to recover the invested time and resources. Years past, we forgot the pain, but never forgot the lesson we learned …

Recently, while involved in a global ministry campaign, we were faced with a similar situation. This time, however, it did not involve business partners, but a multitude of Pentecostal ministers. The larger size of the context did not change the problem at hand, but rather intensified and multiplied its harmful effects. We regretfully witnessed how hundreds of men and women involved in ministry were manipulatively forced to face the same dilemma. They had to make a mandatory choice between the financial security of their families and their own moral integrity. The results were accordingly. Read more