THE PASTORAL TRIALS ELIMINATE THE AVANTGUARD OF BULGARIAN EVANGELICALS FOR AN ENTIRE GENERATION (PART 1)

THE PASTORAL TRIALS ELIMINATE THE AVANT-GARDE OF BULGARIAN EVANGELICALS, BEHEADING IT FOR AN ENTIRE GENERATION (Part 1)

[Editorial note: The following text is translated from the Bulgarian original. The documents contain memorandums, archival records, State Security (Darzhavna Sigurnost / DS) interrogation files, survivor testimonies, and secondary scholarly sources. Bracketed insertions in the original are the author’s. Handwritten portions of the source document are noted where applicable. Archival reference: pp. 155–177.]

Archival Preamble

To Comrade [name illegible in manuscript]. Here! … (p. 1), 155–3pp–177

Comrade Director — in order not to speak in generalities [regarding the arrest warrants and the public punitive proceedings against them as enemies of the Party and the people] and to substantiate my claim, I shall append a list of the names of pastors who completed their education in America or in another foreign country. In addition to their religious fanaticism, they have unquestionably acquired the character and mentality of the ‘secular’ Western democracies. For example…

Vasil Georgiev Zyapkov — Age 47

Completed advanced theological studies in Manchester and New York. Interrogated by the State Security Service and driven nearly to madness before he ‘confessed’ to the creation of a spy network that had sabotaged the ‘people’s authority’ and harmed ‘fraternal relations with the Soviet Union,’ thereby becoming a ‘servant and assistant of the interests of England and the United States.’ According to the scenario written in Sofia and Moscow along the model of [Andrei] Vyshinsky, it was Zyapkov who was cast as the ‘sinister mastermind’ of the entire conspiracy (the so-called ‘espionage centre’). He was initially isolated and subjected to pressure to renounce his beliefs, subsequently blackmailed, and finally arrested in early November 1948. For nearly three months he was interrogated in the cells of the State Security Service together with the other pastors, all of whom were compelled to confess to everything imputed to them.

Zyapkov completed his studies in literature (not theology, as was erroneously believed) in Manchester. He maintained an extensive network of friends in England and America, including family ties, which the State Security Service deemed dangerous and potentially harmful to Bulgaria. At the insistence of Dimitar Furnadzhiev (1867–1944), he succeeded the latter as religious representative of the United Evangelical Churches (OETs). Zyapkov served as pastor of the central Methodist church ‘Dr. Long.’ He was sent by the Congregationalists to their Union Theological Seminary, where he most likely completed his master’s degree in 1932. His participation in the Bulgarian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in the summer of 1946 was subsequently used as an argument at trial that he had established espionage contacts.

Zyapkov’s testimony (under the code name “ЧЕРВЕЙ” / “WORM”) reveals the interrogation techniques employed. Reading the document — written in 1951 and entitled My Confession Regarding the Trial, ostensibly submitted as a letter to the Prime Minister requesting a review of the case — one discovers numerous parallels with the memoirs of Haralan Popov (another of the convicted clergymen). The account of the tortures (more psychological than physical in nature) and the manner in which false confessions were ultimately extracted is replicated in both cases.

Zyapkov wrote that he was rarely beaten (‘only once was my head smashed against the concrete wall’), but that the most tormenting aspects were the ceaseless threats of a death sentence and the blackmailing carried out through his family (e.g., ‘your daughter will become a prostitute’). For weeks he was compelled to write confessions until 11:00 p.m., and was then woken shortly after midnight for lengthy nocturnal interrogations. He was threatened that the sentence would be carried out by execution in the cell. Towards the end of these exhausting interrogations, the prisoners began to experience hallucinations. A new narrative was fabricated in which Floyd Black, the director of the American College in Sofia, and his son Cyril Black were presented as the chief conspirators. The strategic intelligence that Zyapkov had allegedly gathered and transmitted to his purported handlers consisted of the numbers and names of Soviet ships docked in the port of Varna — information he had memorised in order not to compromise his confessions during the trial.

Note: Spas Ivanov Asenov, from the village of Malko Belovo, was sentenced to death in the trial of the ‘Free Warriors’ (anarchists). He shared a cell with Pastor Vasil Zyapkov and stated that he was a non-believer. However, when they led him out to be executed, he said: ‘Farewell! We shall meet above, before God’s gates!’

Together with Zyapkov, all of the more influential spiritual leaders were arrested. The agonising investigation was conducted by interrogators who had honed their inquisitorial cruelty through the interrogations of opposition figures. After months of physical and psychological torment, entirely innocent church workers were reduced to clay figures who, in the satanic tradition of the State Security Service, made their ‘confessions’ to having committed ‘espionage, slander against the people’s authority, and preparations for subversive activities.’ For a full three years after his sentencing, Zyapkov barely managed to return to normal behaviour.

Lambri Marinov Mishkov — Age 40

Completed his studies at the Princeton Theological Seminary. According to K. Grozev, he also studied chemistry at the University of Chicago and subsequently theology at Harvard, and worked towards a doctorate at Cambridge during the 1930s, at which point he was obliged to return to Bulgaria to be at his mother’s bedside in her final days. It is improbable, though not impossible, that the young Mishkov managed to complete so many disparate and numerous programmes of study within the span of approximately twenty years. It is equally possible that his name has been confused with that of his namesake Pavel Mishkov, who did indeed graduate from Chicago. The investigative file records only that he received his theological education at Princeton.

Despite being a clergyman, in 1946 he was invited to serve as an adjunct associate professor of philosophy at the newly founded University of Plovdiv. It was at this time that he published his book

Philosophy of Faith — one of the finest philosophical studies of the philosophy of religion ever written in the Bulgarian language.

- Grozev describes him as an ‘old uncle’ — a close friend of his grandfather. He spoke excellent English, would recount stories of Lincoln, and explained the meaning of the expression ‘monkey business,’ as well as one of the proposed etymologies of the well-known acronym ‘OK.’ Mishkov underwent the same interrogations and tortures as the others, but never confessed to having contacted the American Embassy or received money — an accusation that was ultimately dropped, resulting in a reduced sentence. Under duress, he ‘confessed’ to having transmitted information about the quantity of nails produced (in kilograms) at a factory in Plovdiv, as well as the road map from Plovdiv to Peshtera — a map that could in fact have been purchased at any bookshop. It was precisely this map, the subject of interrogations, that had allegedly been passed by Zyapkov to Cyrus Black, who was also considered part of the supposed spy network.

As with all those convicted, his children were barred from universities, forced to take low-paid manual work, and were permitted to visit their father only once every six months or even less frequently. The elder Grozev repeatedly took Mishkov’s children to prison visits when their mother was ill and the next permitted meeting was still months away.

Simeon Petrov Iliev — Age 37

Completed his studies at the American Scientific Theological School as well as a theological seminary in Switzerland. Following the departure of Kr. Stoyanov, at the initiative of the youth fellowship of the church, he was invited to assume the pastoral ministry in Asenovgrad (then known as Stanimaka). During his pastoral tenure, the church experienced a period of growth. He succeeded in uniting several other Evangelical fellowships, which led to a significant expansion of the church community. Despite the hardships of the post-war years, the new (modern) church building was constructed during this period. Furthermore, the headquarters of the Women’s Missionary Union of the Southern Evangelical Churches was established in Asenovgrad, further strengthening the organisational structure of the Protestant community in the region. Simeon Iliev served as pastor until 1949, when he was arrested and tried on charges of espionage.

Konstantin Stoyanov Marvakov — Age 55

Completed his studies at a theological seminary in Austria. Served as pastor of the church in Yakoruda. He was subjected to repression during the Communist campaign against religious communities in Bulgaria. Accused of espionage, the specific charges including the transmission of information concerning the annual harvest in the Chirpan region, as well as the production capacity of the oil-press in the village of Marichleri. These charges were formulated within the same framework as the case against Lambri Mishkov, with all alleged evidence reduced to a single page in the investigative file. This underscores the characteristic method of fabricating accusations in this period, whereby insignificant or publicly available information was interpreted as a threat to state security, in order to justify politically motivated repression.

Kiril Yotov Vladov — Age 43

Completed his studies in Frankfurt. Attended the men’s gymnasium in Pleven, and was subsequently recruited as an assistant pastor at the Sofia Methodist church ‘Dr. Long,’ where he worked and developed under the guidance of Pastor Vasil Zyapkov. He completed his theological education alongside future pastors Litov and Sivriev at the Methodist Seminary in Frankfurt, where he met his future wife, Maria Schmeissner, whom he married in 1931. In 1939 he was transferred to the Pleven Methodist church, replacing Pastor Yanko Ivanov.

As early as 10 September 1944, Soviet soldiers were quartered in the pastor’s residence. Two days later, a group of armed civilians burst into the house and conducted a search, their leader declaring: ‘You are under arrest! Take only the barest essentials — a little food and clothing — for we are taking you to Pleven prison.’ Pastor Yotov asked: ‘May we pray before you take us to prison?’ After the brief prayer, it was as though everything had changed. The leader of the arresting party began to calm those under arrest. The children were taken in by Miss Mara Gaytandzhieva and later sent to the village of Burkach to their grandmother. Before long, Maria returned, but completely changed — the time spent in prison remained with her for the rest of her life. Kiril Yotov spent eight months behind bars, enduring brutal torture and beatings.

In 1948 Kiril Yotov was arrested again in connection with the already-commenced Pastoral Trials. As a local prisoner, he was transferred from the Ministry of the Interior in Pazardzhik to Plovdiv, and ultimately to the investigative detention facility in Sofia. He was accused of supplying information concerning the annual harvest in Aprilsko and Tserov, the annual yield of winter crops, and the grape harvest. Beaten with leather belts and whips that tore entire strips of flesh from his back, in order to compel a confession — yet he did not lose his faith or his optimism. The Communists failed to break him and did not include him in the trial, as he was unpredictable and liable to disrupt their pre-arranged scenario. He was ultimately transferred to the ‘Bobov Dol’ labour camp and subsequently sent to Belene. His home was confiscated by the local authorities and his family was forced to relocate to Sofia. His wife Maria Yotova made extraordinary efforts to support the family, but the children were deemed politically unreliable and expelled from all youth organisations.

As no one could send him money from the outside, he acquired a razor, soap, and a rusty blade with which he shaved and cut the hair of his fellow camp inmates at Belene. In the summer of 1953, after five years in camps and prisons, Pastor Kiril Yotov was released. His family scarcely recognised him. At the time of his arrest he had been a healthy man weighing 85 kilograms; after five years he emerged emaciated, barely 48 kilograms — a frail body, but an unbroken spirit and a smile on his face. He recalled with pain the countless worthy individuals who had been oppressed, tortured, and humiliated.

Kostadin Spasov Bozovayski — Age 35

Theologian. Completed his seminary studies in Kassel and London, England. Born on 11 February 1912 in the village of Stob, Dupnitsa region. He served as pastor in Haskovo, following Vatralski, Furnadzhiev, and Gradinakov, and from 1956 served for three years as pastor in Asenovgrad. Until 1959 he was one of the few pastors not yet affected by the regime’s repression. When the Pastoral Trials commenced, Bozovayski was serving as treasurer at the ‘Pirin’ factories in Kardzhali whilst simultaneously serving as pastor of the Congregational church in the city. Upon his arrest, the charge was raised that he was a committed Germanophile, associating exclusively with reactionaries and the German specialists working in Kardzhali. He received various sums from different parts of Bulgaria, as well as numerous parcels from America, where his two brothers resided, with whom he maintained uninterrupted contact. In 1945 he attended the pastoral gathering of the United Evangelical Churches (OETs) in Burgas. He allegedly supplied ‘information regarding the annual production of the Pirin mine, the warehouses in Kardzhali, and tobacco production.’ The information was said to have been written on a typewriter.

Following the trials, already retired, Bozovayski served as chairman of the Congregational Church in Bulgaria and pastor of the mother church at 49 ‘V. Kolarov’ Street. He was repeatedly summoned before the [State] Committee, where Virchev, Totev, and Timotei Mikhailov were proposed to him as deputies. He refused, as they did not belong to the congregational churches, and Mikhailov was not even an ordained pastor. ‘You will ordain him,’ the director Tsvetkov ordered.

The authorities sought a financial audit with the aim of removing the Kulichev brothers on charges of hooliganism, including breaking down the church door with an axe. The Committee attempted to replace Pastor Bozovayski, but the congregation rejected the new appointment. ‘This question will be resolved definitively this year,’ the Party functionaries warned. ‘The leadership and ordinary membership is considerably aged… the church’s capacity for religious influence is rather weak,’ the Committee’s report noted.

Krum Georgiev Bumbanov — Age 43

Completed his studies at a seminary in Austria. Born in the village of Ognyanov (also known as Banya), he served as pastor of the church in Haskovo, following Vatralski, Furnadzhiev, Gradinakov, and Bozovayski. While serving in Yakoruda, he preached together with Angel Kremenliev in Bansko, Eleshnitsa, and Razlog. Brought as a defendant on the charge that he supplied information regarding the annual production of the dairies and the harvest in the Razlog region, as well as the summer crops in the area. His son, Danail Bumbanov, was arrested together with him in the course of the Pastoral Trials.

Sarkis Bedros Manukyan

Completed his studies in Kingston, Canada. His name appeared on the masthead of every issue of the Evangelical newspaper Zornitsa [Dawn].

Pavel Hristov Nikolov — Age 49

Completed advanced theological education at Oxford. Served as pastor of the church in Plovdiv before Zyapkov.

Nikola Borisov Dimitrov — Age 42

Completed his studies at a theological seminary in Bangor (USA — not the University of Bangor in England).

Yosif Isakov Danailov — Age 49

Completed his studies in Austria and England. A widely published Bulgarian man of letters. In 1952 he was the subject of a notice from the Presidium of the National Assembly: ‘Yosif Isakov Danailov, former resident of the city of Sofia, now of unknown address. I hereby notify you that under Enforcement Order No. 2132/1951, issued by the Sofia District Court, you have been sentenced to pay…’

Atanas Angelov Kremenliev — Age 37

Completed his studies at a seminary in the USA. Maintained close ties with Zyapkov and Pastor Isakov. He is mentioned in an explicit directive of the State Security Service: ‘Demonstrate that the defendants will be held accountable solely for their espionage [activities].’ Immediately following the exile of Pastor Trifon Ivanov, sentenced to eight years, Pastor Kremenliev was sent to the camp near Yakoruda with a rather unusual annotation regarding the conversion of Jews to Christianity.

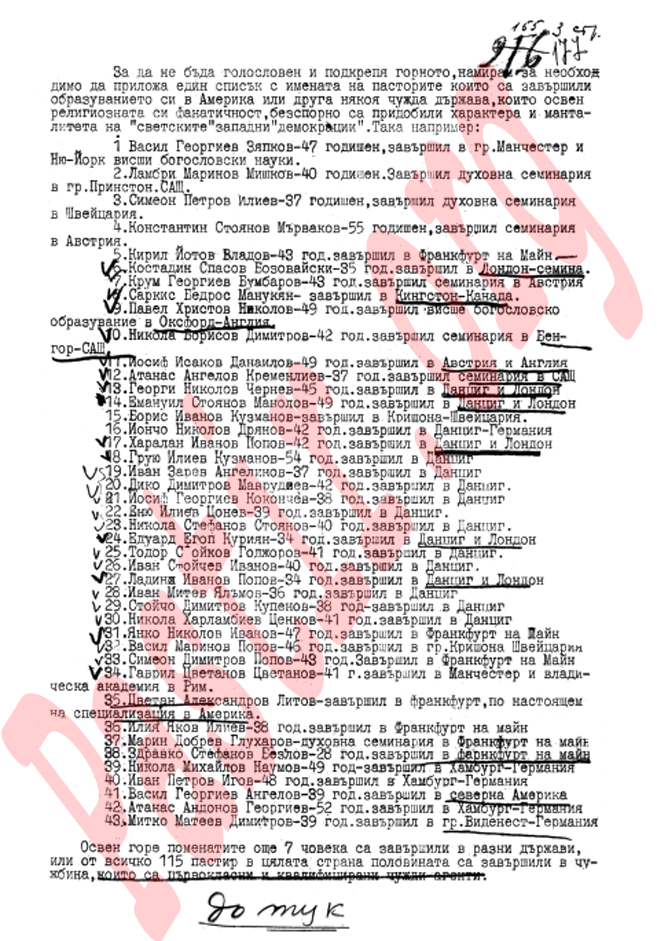

Translated from the list with pastors from the document above:

LIST OF BULGARIAN EVANGELICAL PASTORS WHO COMPLETED THEIR EDUCATION ABROAD

State Security Service Memorandum, 1948

Archival Reference: 155/3/177

Editorial note: The following is a complete transcription and translation of the archival document photographed at pastir.org. Text underlined in the original manuscript is rendered with underline formatting below. A handwritten annotation reading ‘до тук’ (‘to here’) appears at the foot of the original page, indicating the end of the handwritten portion of the document. Checkmarks (✓) visible in the original against certain entries are noted in brackets. The preamble and closing summary are translated verbatim from the Bulgarian.

Preamble (verbatim translation): ‘In order not to speak in generalities and to substantiate the foregoing, I find it necessary to append a list of the names of the pastors who completed their education in America or in some other foreign country, who, in addition to their religious fanaticism, have unquestionably acquired the character and mentality of the “secular” Western democracies. For example:’

THE LIST

- Vasil Georgiev Zyapkov — age 47. Completed advanced theological studies in Manchester and New York.

- Lambri Marinov Mishkov — age 40. Completed his studies at the theological seminary in Princeton, USA.

- Simeon Petrov Iliev — age 37. Completed his studies at a theological seminary in Switzerland.

- Konstantin Stoyanov Marvakov — age 55. Completed his studies at a seminary in Austria.

- Kiril Yotov Vladov — age 43. Completed his studies in Frankfurt am Main.

- Kostadin Spasov Bozovayski — age 35. Completed his studies in London — Seminary.

- Krum Georgiev Bumbakov — age 43. Completed his studies at a seminary in Austria.

- Sarkis Bedros Manukyan. Completed his studies in Kingston, Canada.

- Pavel Hristov Nikolov — age 49. Completed advanced theological education in Oxford, England.

- Nikola Borisov Dimitrov — age 42. Completed his studies at a seminary in Bangor, USA.

- Yosif Isakov Danailov — age 49. Completed his studies in Austria and England.

- Atanas Angelov Kremenliev — age 37. Completed his studies at a seminary in the USA.

- Georgi Nikolov Chernev — age 45. Completed his studies in Danzig and London.

- Emanuil Stoyanov Manolov — age 49. Completed his studies in Danzig and London.

- Boris Ivanov Kuzmanov. Completed his studies in Krichona — Switzerland.

- Yoncho Nikolov Dryanov — age 42. Completed his studies in Danzig — Germany.

- Haralan Ivanov Popov — age 47. Completed his studies in Danzig and London.

- Gruy Iliev Kuzmanov — age 54. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Ivan Zerev Angelinov — age 37. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Diko Dimitrov Mavrudaev — age 42. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Yosif Georgiev Kokonchev — age 38. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Enyu Iliev Tsonev — age 39. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Nikola Stefanov Stoyanov — age 40. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Eduard Agop Kuriyan — age 34. Completed his studies in Danzig and London.

- Todor Stoykov Godjorov — age 41. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Ivan Stoychev Ivanov — age 40. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Ladin Ivanov Popov — age 34. Completed his studies in Danzig and London.

- Ivan Mitev Yalamov — age 36. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Stoicho Dimitrov Kupenov — age 38. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Nikola Harlamiev Tsenkov — age 41. Completed his studies in Danzig.

- Yanko Nikolov Ivanov — age 47. Completed his studies in Frankfurt am Main.

- Vasil Marinov Popov — age 45. Completed his studies in Krichona, Switzerland.

- Simeon Dimitrov Popov — age 43. Completed his studies in Frankfurt am Main.

- Gavril Tsvetanov Tsvetanov — age 41. Completed his studies in Manchester and at the episcopal academy in Rome.

- Tsvetan Alexandrov Litov. Completed his studies in Frankfurt; currently specialising in America.

- Iliya Yakov Iliev — age 38. Completed his studies in Frankfurt am Main.

- Marin Dobrev Gluharov. Completed his studies at the theological seminary in Frankfurt am Main.

- Zdravko Stefanov Bezlov — age 28. Completed his studies in Frankfurt am Main.

- Nikola Mikhailov Naumov — age 49. Completed his studies in Hamburg — Germany.

- Ivan Petrov Igov — age 48. Completed his studies in Hamburg — Germany.

- Vasil Georgiev Angelov — age 39. Completed his studies in northern America.

- Atanas Andonov Georgiev — age 52. Completed his studies in Hamburg — Germany.

- Mitko Mateyev Dimitrov — age 39. Completed his studies in Wilenest — Germany.

Closing Summary (verbatim translation):

‘In addition to the above-mentioned, a further 7 individuals completed their studies in various countries. Thus, of a total of 115 pastors throughout the entire country, half completed their education abroad — who are accordingly first-class and qualified foreign agents.’

Handwritten annotation at foot of document: ‘до тук’ (‘to here’) — indicating the end of the handwritten portion of the memorandum.

Translator’s Notes

- Entries marked with ✓ in the original document are reproduced here with that symbol. The significance of the checkmarks is not explained in the source; they may denote individuals already arrested, already under surveillance, or prioritised for prosecution at the time of the document’s compilation.

- Underlined text in the original (indicating institutions and cities) is preserved with underline formatting.

- ‘Danzig’ refers to the Free Theological Academy (Freie Theologische Akademie) in the Free City of Danzig (present-day Gdańsk, Poland), which served as the principal training institution for Bulgarian Pentecostal pastors throughout the 1930s.

- ‘Krichona’ refers to the St. Chrischona Pilgrim Mission (Pilgermission St. Chrischona) near Basel, a pietist missionary training institution.

- ‘Wilenest — Germany’ in entry 43 is likely a transcription error or phonetic rendering in the original Bulgarian; the precise institution has not been identified.

- The document bears the archival reference 155/3/177 and is reproduced at pastir.org. The preamble and closing summary are in typewritten Bulgarian; the annotation ‘до тук’ (‘to here’) is handwritten.

- The assertion that foreign-educated pastors are ‘first-class and qualified foreign agents’ represents the operative ideological premise of the 1948–1949 Pastoral Trials — that Western theological education was itself evidence of intelligence recruitment.

Bulgarian government resigns amid protests

365 Daily Thought Stirring Stories from the Field

In 1999, Dony and Kathryn established Cup & Cross Ministries International with a vision for restoration of New Testament theology and praxis. Today they have over 50 years of combined commitment to Kingdom work. This book invites you to spend a few moments each day on the field sharing their experiences of serving as pastors, evangelists, chaplains, consultants, church trainers, researchers, missionaries and educators of His Harvest around the globe.

Dony Donev: Theological Work in Pentecostal Studies

Dony Donev is known for his theological work, particularly in the context of Pentecostal studies. While he may not have a widely recognized catalog of specific terms or frameworks that have achieved broad usage, he has contributed significantly to the academic field through his research and writings.

Theological Contributions

-

Pentecostal Studies: Donev’s work often focuses on Pentecostal theology, examining its historical development, doctrinal distinctives, and contemporary implications.

-

Contextual Theology: He explores how Pentecostal theology interacts with cultural and societal contexts, particularly in Eastern Europe.

-

Pentecostal Hermeneutics: Donev might have contributed to discussions about how Pentecostals interpret the Bible, emphasizing a Spirit-led reading of the Scriptures.

Key Terms or Concepts

-

Emerging Pentecostal Identity: A possible area of focus where Donev discusses how Pentecostal identities are evolving in the modern world, including how they reconcile traditional beliefs with contemporary contexts.

-

Cultural Engagement: A term that may be used to describe his analysis of Pentecostalism’s role in engaging with and transforming culture.

For more specific terms or frameworks coined by Dony Donev, it would be beneficial to consult his published works or academic papers.

Pentecostal primitivism is a concept within Pentecostal theology emphasizing a return to the faith and practices of the early Christian church. Here’s an overview:

Key Aspects of Pentecostal Primitivism

Restoration of Apostolic Practices

- Focus on Original Christianity: Emphasizes the imitation of New Testament church dynamics, including spiritual gifts.

- Spirit-Led Worship: Encourages direct experiences with the Holy Spirit, akin to early church practices.

Doctrinal Simplicity

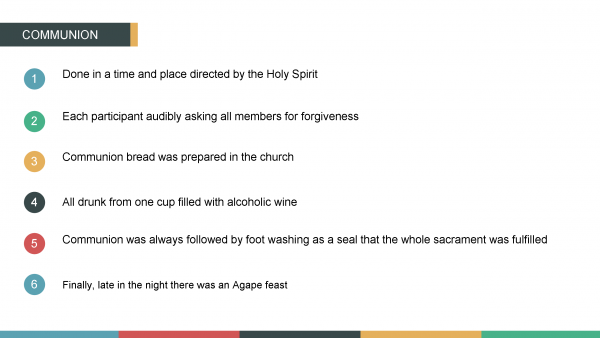

Primary Framework: The USHER Model of Communion

The U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion (or USHER Model)

-

Creator: Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

-

Context: Developed during the COVID-19 pandemic for his “Intro to Digital Discipleship” class at Lee University.

-

Core Purpose: To answer the question “What follows communion?” in Christian practice and catechism. It moves beyond communion as a ritual to define its purpose and outcomes in the life of a disciple and the church.

-

The Five Dynamics:

-

U – Unity: Communion fosters spiritual unity among believers, breaking down barriers and creating one body in Christ.

-

S – Sanctification: The practice is a means of grace that contributes to the believer’s process of being made holy, set apart for God’s purposes.

-

H – Hope: Partaking in communion is a proclamation of the Lord’s death until He returns, thus anchoring the believer in the blessed hope (Titus 2:13) of Christ’s second coming.

-

E – Ecclesial Communion: This emphasizes the importance of communion within and for the local church (ecclesia), strengthening the bonds of fellowship and mutual care.

-

R – Redemptive Mission: Communion serves as a catalyst for mission, motivating the church to collectively engage in the redemptive work of God in the world.

-

Other Associated Frameworks and Concepts

Dr. Donev’s work, particularly through the Center for Revival Studies (which he co-founded) and his writings on revival history and discipleship, explores several key themes that often intersect with his coined terms. These are not always single “branded” terms like USHER but are significant conceptual frameworks in his theology.

-

Digital Discipleship:

-

While not a term he solely coined, he has been a primary architect of its theological framework. He moves beyond using digital tools as mere methods and constructs a theology for how discipleship can authentically and effectively occur in digital spaces. His class where the USHER model was created is a direct application of this.

-

-

Theology of Revivalism:

-

Donev’s work heavily focuses on defining and analyzing revival, particularly from a historical (e.g., Balkan, Slavic, and Pentecostal) perspective. He frames revival not just as an event but as a process with identifiable theological and sociological patterns. His book “The Covenant of Peace: God’s Dream for the World” delves into this.

-

-

Covenant Community:

-

A recurring theme in his work is the concept of the church as a covenant community. This framework views the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants, which directly connects to the “Unity” and “Ecclesial Communion” aspects of the USHER model.

-

-

The “Why” of Discipleship:

-

Much of Donev’s writing and teaching focuses on moving beyond the “how” to the “why” of spiritual practices. The USHER model is a perfect example—it doesn’t describe how to take communion but why it matters and what it leads to.

-

Summary Table for Clarity

| Term/Framework | Description | Key Context |

|---|---|---|

| USHER Model of Communion | Primary Coined Term. A 5-point framework (Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, Redemptive mission) defining the outcomes of communion. | Digital Discipleship, Catechism, Liturgy |

| Digital Discipleship | A theological framework for making disciples in online/digital environments, moving beyond mere methodology. | Modern Ministry, Post-COVID Church, Technology & Theology |

| Theology of Revivalism | A framework for understanding revival as a historical and theological process with identifiable patterns. | Church History, Pentecostal Studies, Spiritual Renewal |

| Covenant Community | A conceptual framework viewing the church’s identity and mission through the lens of biblical covenants. | Ecclesiology (Doctrine of the Church), Community Formation |

In essence, while the USHER Model of Communion is his most clearly defined and coined term, Dr. Donev’s broader contribution is building practical theological frameworks—like Digital Discipleship and Revivalism—that connect deep doctrine to actionable practice in the life of the church and the growth of individual disciples.

Dony Donev: Theological Framework Centered on Neo-primitivism

Dony Donev’s theological framework is centered on neo-primitivism, which he describes as a return to the “basic order of the Primitive Church of the first century”. Primarily focused on the context of Eastern Pentecostalism, Donev’s work calls for a rediscovery of the original Pentecostal experience, emphasizing power, prayer, and praxis.

Coined terms and key concepts

Neo-primitivism: This is the central concept in Donev’s framework, which he coined in his book Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved. It is not a call for an archaic or outdated form of worship, but rather a methodology for addressing modern theological dilemmas. Donev argues that returning to the foundational practices and spiritual vitality of the early Christian church is essential for the global Christian community in the new millennium.

Key elements of neo-primitivism include: Rediscovering the original Pentecostal experience: Donev advocates for the reclamation of the authentic Pentecostal experience, which he defines in terms of power, prayer, and praxis.

Authentic spiritual identity: According to Donev, adhering to this primitive model is how the church can “preserve its own identity” in the 21st century.

Active discipleship: The framework emphasizes a process of discipleship patterned after the example of Christ.

Eastern Pentecostal Tradition

While not a coined term, Donev’s work is deeply rooted in and builds upon the unique history and theology of the Eastern Pentecostal Tradition. He draws heavily from his own Bulgarian background, highlighting the historical roots of Pentecostalism in Eastern Europe, as detailed in his book The Unforgotten: Historical and Theological Roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria.

Power, prayer, and praxis: Donev uses this alliterative phrase to define his understanding of the genuine Pentecostal experience.

- Power: Refers to the supernatural empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

- Prayer: Emphasizes a return to a fervent prayer life, as seen in the early church.

- Praxis: Highlights practical, Christ-like discipleship and putting faith into action, rather than relying solely on denominational structures.

Donev’s theological concerns

Donev developed his frameworks in response to what he saw as a crisis in the modern church, which he describes as facing “new existential dilemmas”. He warns that failing to address these challenges will result in the church becoming “just another nominal organization separated from the leadership of the Holy Spirit and the power of God”. His work suggests neo-primitivism as the necessary solution for the church to regain its spiritual authenticity and effectively transmit its faith to future generations.

The Practice of Corporate Holiness within the Communion Service of Bulgarian Pentecostals

by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals (Research presentation prepared for the Society of Pentecostal Studies, Seattle, 2013 – Lakeland, 2015, thesis in partial fulfillment of the degree of D. Phil., Trinity College)

Pentecostal identity was corporately practiced and celebrated within the fellowship of believers through the partaking of Holy Communion. We have otherwise extensively described the Communion service among Bulgaria’s conservatives in Theology of the Persecuted Church (Part 1: Lord’s Supper https://cupandcross.com/theology-of-the-persecuted-church/). Therefore, here we offer just a brief overview of its main characteristics.

- It was done in a time and place directed by the Holy Spirit

- If some did not have water baptism they were taken to a close by river to be baptized while the rest of the church prayed

- Upon returning, if some did not have yet the baptism with the Holy Spirit, the church would pray until all were baptized

- It began with each participant audibly asking all members for forgiveness

- they would also audible respond with the words: WE FORGIVE YOU and may GOD also forgive you

- The communion bread was prepared on the spot baked by women whose names were also reveled in prayer

- All drank from one cup, which strangely for their strict practice of abstinence from alcohol, was filled with alcoholic wine

- Communion was served only to those who had the fullness of the Spirit, and had just requested and were given forgiveness

- The presbyter would quote Jude 20 to each partaking believer thus directing them to audibly speak in tongues before they could participate in communion

- Interpretation often followed to confirm the spiritual stand of the believer

- If there were any leftovers, the Communion elements were served again until all was used

- Communion was incomplete without foot washing as a seal that the whole sacrament was fulfilled.

Standing Firm in the Bible Belt Responding to a Resurgence of Witchcraft

Patricia Crowther passed away in September 2025 at the age of 97 from complications related to dementia. Crowther was one of the last direct cult-initiate of Gerald Gardner, often called the “father” of modern Wicca. For the past 75 years followers of Gardnerian Wicca have distorted truths teaching their beliefs as a spiritual path of reclamation, healing, and reverence for nature.

With her death, many adherents of modern paganism and witchcraft have felt motivated to interpret her passing as a moment of transitional resurgence. Her widespread hold has influenced new seekers and fringe groups to draw inspiration from her work, especially in places where spiritual vacuum or dissatisfaction with organized religion is strong.

In the rural parts of the Bible Belt like Tennessee, this phenomenon has posed particular challenges such as the following:

- Spiritual vulnerability: Some in isolated or economically struggling areas may be more open to alternative spiritualities if they feel the established church has failed them.

- Cultural tensions: Witchcraft or occult practices can intensify spiritual conflict, foster anxiety about “demonic influence,” or create fear and division in close communities.

- Distraction from the work of the Gospel: If congregations become preoccupied with spiritual warfare or defensive postures, that may drain resources from evangelism, discipleship, social outreach, and community care.

Thus, this death, rather than closing a chapter, may galvanize increased activity among her followers and deepen the spiritual battleground in regions already steeped in Christian faith. Prayer, fasting and standing firm with His light is the only force that will prevail against the darkness.

A Call for Righteousness over Orthodoxy

The Digital Ecclesia: A Theological Exploration

In the contemporary ecclesial landscape, the Seventh-day Adventist Church stands at a pivotal juncture, grappling with the imperatives of the Great Commission in a digital age. The biblical mandate to “go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation” (Mark 16:15, NIV) resonates profoundly in an era where approximately 42% of the global population engages with social media, as noted in mid-2019 data. This thesis posits that digital communications, far from being a peripheral tool, represent a divinely ordained extension of the apostolic mission, akin to the School of Tyrannus in Ephesus where Paul’s teachings “went viral” through oral dissemination (Acts 19:8-10, NASB). Drawing from personal ecclesial campaigns and broader theological reflections, this essay argues that transforming digital influence into global impact necessitates a paradigm shift from linear evangelism models to holistic, empathetic digital discipleship. By integrating scriptural precedents, empirical evidence from church initiatives, and case studies, we explore how the Church can leverage digital tools to reach the “unreachable,” foster cultural empathy, and cultivate disciples who embody Christ’s relational ethos. This analysis underscores the theological imperative for strategic digital engagement, ensuring the gospel permeates intersecting cultures in both virtual and physical realms.

The Theological Foundation of Digital Influence as Missional Extension: Theologically, digital communications echo the incarnational ministry of Christ, who met people where they were, adapting to their cultural paradigms (1 Corinthians 9:19-23, NASB). The text under examination illustrates this through a 2016 campaign for the “Your Best Pathway to Health” mega-health clinic in Beckley, West Virginia, Appalachia—a region stereotyped as technologically disconnected. With a modest $200 budget, targeted Facebook ads reached 200,000 users within a 50-mile radius, outperforming traditional media like flyers and newspapers in exit surveys. Testimonials revealed that online ads prompted offline sharing: family members and friends, not on social media, were informed and attended, embodying the Samaritan woman’s evangelistic zeal (John 4:28-30, NIV).This case study provides empirical proof of digital tools’ amplification power. A New York Times study cited in the text affirms that 94% of people share online content to improve others’ lives, aligning with human nature’s propensity for communal benevolence. Theologically, this mirrors the early Church’s organic spread: Paul’s stationary ministry in Ephesus disseminated the gospel across Asia via travelers who “liked and shared” his message verbally, reaching Jews and Greeks alike (Acts 19:10). In modern terms, social media serves as the “modern School of Tyrannus,” a digital agora for idea exchange. Evidence from the Beckley campaign demonstrates that targeting the connected 42% activates networks bridging to the 58% offline, challenging assumptions of digital irrelevance in underserved areas. The author’s personal rebuttal to a friend’s skepticism—rooted in data over presumption—highlights ecclesial resistance to innovation, yet the results validate a Pauline strategy scaled by technology: reach the reachable to evangelize the unreached.

With members spanning nations, tribes, and tongues, digital tools empower diaspora connections. For isolated communities, the text invokes the Holy Spirit’s sovereignty, recalling Mark 16:15’s call not as human achievement but divine partnership. This theological framework—evangelism as relational sharing—counters secular digital marketing’s transactionalism, emphasizing discipleship’s transformative ethos. The Beckley initiative’s success, where social media rivaled word-of-mouth referrals, proves that digital influence transcends virtual boundaries, fostering real-world attendance and healing, thus fulfilling the Church’s wholistic mission of body and soul.

From Linear Paths to Journey Loops: Reimagining the Seeker’s Spiritual Pilgrimage

Traditional evangelism’s linear funnel—from awareness to membership—mirrors outdated marketing but falters in a post-modern, multicultural world of “intersecting cultures.” The text critiques this model, advocating a “Seeker’s Journey” with non-linear loops: “See” (Awareness), “Think” (Consideration), “Do” (Visit/Engage), “Care” (Relationship/Service), and “Stay” (Loyalty/Membership). This systems-thinking approach, drawing from Margaret Rouse’s definition of interrelated elements achieving communal goals, reflects the Holy Spirit’s dynamic work, not mechanistic conversion.

Proof emerges from the modified digital funnel, integrating traditional and digital strategies. Exposure via organic traffic, ads, and word-of-mouth feeds discovery, where seekers consume content and assess relevance. Consideration evaluates “digital curb appeal,” leading to engagement—visits, Bible studies, or prayer requests. Relationship-building through empathetic follow-up and text evangelism sustains loyalty, looping disciples back as creators and engagers. A case study implicit in the text is the author’s transition from secular marketing to church application: pre-clinic prayers yielded testimonies of digital-driven attendance, with social media second only to personal referrals. This evidences the funnel’s efficacy, where engagers span touchpoints, building bridges from online anonymity to in-person commitment.

Theologically, this resonates with Paul’s adaptability: “I have become all things to all people, that by all possible means I might save some” (1 Corinthians 9:22, NIV). In a world of migrants and global connections, even static communities like the author’s Appalachian hometown—lacking cell reception yet tied via satellite—illustrate digital reach. The text’s personal anecdote of introducing Adventism to parents through conversations exemplifies empowering insiders: migrants from remote areas, digitally connected, share culturally attuned gospel messages upon return visits. Data from Pew underscores Adventism’s diversity as a missional asset, yet untapped digitally. The journey loops counter assumptions of homogeneity, promoting cultural empathy—empowering community members as evangelists, much like the Ethiopian eunuch’s self-directed study via Philip’s guidance (Acts 8:26-40). By magnifying friendship evangelism, digital tools enable 24/7 kingdom pursuit, measuring success not by pew counts but disciple formation, echoing Jesus’ relational model over programmatic faith.

Cultivating Cultural Empathy: Audience Personas and Generational Dynamics in Ecclesial Outreach

Effective digital evangelism demands “cultural empathy,” expanding culture beyond geography to encompass platforms, generations, and identities. The text warns against “Adventist-speak” barriers, urging internal (church members) versus external (community) vernacular distinctions. Personas—fictional archetypes blending demographics, needs, and values—humanize audiences, fostering resonance. For instance, “Bryce,” a 17-year-old Hispanic Adventist college aspirant, embodies challenges like rejection and doubt, valuing diversity and mentorship. Messages like “We are all adopted into God’s family” address his core, proving personas’ evangelistic utility.Empirical evidence from surveys and analytics validates this: deeper connections via shared experiences transcend surface demographics, yielding loyalty. The text’s framework—surface (age, location) to deep (needs like spiritual community, justice)—aligns with 1 Corinthians 9’s missional flexibility. A key case study is Generation Z (1997-2012), the least religious cohort per Pew, with 35% unaffiliated and short attention spans favoring visuals over text. Yet, 60% seek world-benefiting work and 76% environmental concern, presenting opportunities for a “social gospel” of action. The iPhone’s primacy in their historical narrative underscores technology’s reshaping of connection, demanding Church innovation. Millennials, similarly departing, highlight the urgency: without adaptation, institutions risk obsolescence, as W. Edwards Deming quipped, “Survival is not mandatory.”

Theologically, this echoes Ecclesiastes 1:9-11’s cyclical generations, analyzed in Pendulum by Williams and Drew. The current “We” swing (peaking 2023) favors authenticity, teamwork, and humility over “Me” individualism. Examples include L’Oréal’s slogan shift from “I’m worth it” to “You’re worth it,” and the U.S. Army’s “Army Strong” emphasizing collective resilience. Gorgeous2God, a youth ministry tackling rape and depression candidly, exemplifies “We” values: 45,000 social followers and 20,000 annual website visitors stem from transparent storytelling, disarming via “self-effacing transparency.” This counters Church sluggishness, empowering youth as generational evangelists. By unpacking intersecting cultures—e.g., immigrants versus transplants—the Church bridges gaps, fulfilling Revelation 7:9’s multicultural vision. Personas and empathy ensure messages resonate, turning digital platforms into loci of divine encounter

Strategic Implementation: Tools, Teams, and Metrics for Ecclesial Digital StewardshipDigital tools—social media, email, podcasts, SEO—democratize gospel dissemination, yet require strategic stewardship. The text defines them as binary-processed devices enabling instantaneous global connection, integral for local mission in secular North America. With 1.2 million Adventists across 5,500 churches, untapped potential abounds: digital amplifies relationships, revealing felt needs for targeted service.

The Digital Discipleship and Evangelism Model integrates creators (content packaging), distributors (promotion), and engagers (relational dialogue), holistically scaling traditional evangelism. A sample Digital Bible Worker job description illustrates: responsibilities include content calendars, ads, livestreamed studies, and mentoring, bridging digital to in-person. Case evidence: youth spending 9-18 screen hours daily affords entry at their comfort, anonymity fostering trust.

Leadership must audit platforms, analyze data, and set KPIs—activity (posts), reach (impressions), engagement (shares), conversion (baptisms), retention (testimonials). The “Rule of 7” mandates multi-channel reinforcement amid 3,000 daily ad exposures. Budgets scale: $300 locally yields community awareness; $3,000 nationally drives impact. Batch-scheduling via calendars ensures proactivity, as in the Beckley campaign’s data-driven targeting.

Theologically, this stewards talents (1 Corinthians 12), empowering youth and “social butterflies” in multi-generational teams. Training counters silos, ensuring seamless online-offline continuity. Metrics prioritize kingdom growth over metrics, echoing Jesus’ parables of patient sowing (Mark 4:26-29). By serving needs first—”People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care”—digital strategies build trust, inviting gospel response.

Conclusion: This ecclesial theological inquiry affirms digital influence’s transformative potential for global impact, rooted in scriptural relationality and evidenced by campaigns like Beckley. From journey loops to empathetic personas, strategic tools empower the diverse Adventist body to fulfill Mark 16:15 digitally. Challenges—assumptions, generational shifts—yield to Holy Spirit-led adaptation, as Paul’s Ephesian model scaled virally. Churches must audit, train, and budget intentionally, measuring disciple depth over breadth. Ultimately, digital evangelism incarnates Christ’s empathy, turning virtual connections into eternal kingdom harvests. As we commit to two years of faithful sharing—like Paul—the gospel will proliferate, proving no limitation on the Spirit in our hyper-connected age. The Church, as movement not institution, thrives by embracing this digital mandate, ensuring every nation hears the good news.