Bulgarian Pentecostalism at ORU

December 10, 2023 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, Missions, News, Publication

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PENTECOSTAL MOVEMENT IN BULGARIA

Publication: Society for Pentecostal Studies Annual Meeting Papers (ORU Only Access)

Download Date: 03/2021

SPIRIT-EMPOWERMENT OF THE POOR IN SPIRIT: DR. NICHOLAS NIKOLOV AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE BULGARIAN ASSEMBLIES OF GOD IN 1928

Publication: Society for Pentecostal Studies Annual Meeting Papers (ORU Only Access)

Download Date: 03/2018

“Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis Among Bulgarian Pentecostals”

Publication: Society for Pentecostal Studies Annual Meeting Papers (ORU Only Access)

Download Date: 01/2015

The (Un)Forgotten: Story of the Voronaev Children

Publication: Society for Pentecostal Studies Annual Meeting Papers (ORU Only Access)

Download Date: 01/2011

BULGARIA in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism (BEGP) provides a comprehensive overview of worldwide Pentecostalism from a range of disciplinary perspectives. It offers analysis at the level of specific countries and regions, historical figures, movements and organizations, and particular topics and themes. The online version of the Encyclopedia is already available

For some of you it has been a long time ago that you submitted your article(s) for BEGP, for others it was a bit more recent, but I am very happy to announce that this Summer the print edition of Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism will finally see the light. With this we can proudly close this chapter and proceed to see what the reception of the volume will bring! Thank you for being part of this great project!

To celebrate, we will organize an online symposium on September 16th, with presentations from the editors as well as 3 experts who will comment on BEGP: Amos Yong, Birgit Meyer and Néstor Medina. You can find more detailed information in the attached flyer. Please be welcome.

Registration is free (but necessary to receive a link); we will raffle one free copy of the print edition among the registered participants. For registration and questions, please send your message to [email protected], mentioning Symposium in the subject line.

We hope to see you then!

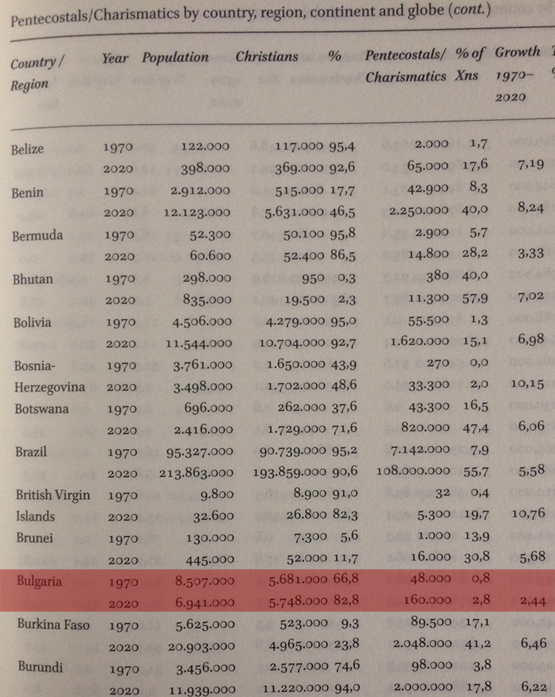

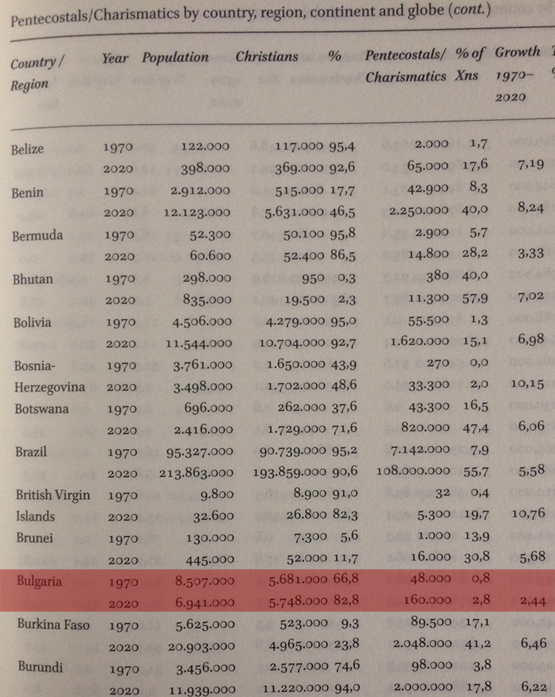

160,000 Pentecostals in Bulgaria Reported by the NEW Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism

160,000 Pentecostals in Bulgaria Reported by the NEW Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism

BULGARIA in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism (BEGP) provides a comprehensive overview of worldwide Pentecostalism from a range of disciplinary perspectives. It offers analysis at the level of specific countries and regions, historical figures, movements and organizations, and particular topics and themes. The online version of the Encyclopedia is already available

For some of you it has been a long time ago that you submitted your article(s) for BEGP, for others it was a bit more recent, but I am very happy to announce that this Summer the print edition of Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism will finally see the light. With this we can proudly close this chapter and proceed to see what the reception of the volume will bring! Thank you for being part of this great project!

To celebrate, we will organize an online symposium on September 16th, with presentations from the editors as well as 3 experts who will comment on BEGP: Amos Yong, Birgit Meyer and Néstor Medina. You can find more detailed information in the attached flyer. Please be welcome.

Registration is free (but necessary to receive a link); we will raffle one free copy of the print edition among the registered participants. For registration and questions, please send your message to [email protected], mentioning Symposium in the subject line.

We hope to see you then!

Brill’s Encyclopaedia of Global Pentecostalism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism (BEGP) provides a comprehensive overview of worldwide Pentecostalism from a range of disciplinary perspectives. It offers analysis at the level of specific countries and regions, historical figures, movements and organizations, and particular topics and themes. The online version of the Encyclopedia is already available

Postmodern Pilgrims

The EPIC Church: Sweet calls his postmodern![postmodern.pilgrims[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/postmodern.pilgrims1.jpg) paradigm the EPIC church where the acronym EPIC stands for:

paradigm the EPIC church where the acronym EPIC stands for:

Experiential (rooted in relationships and personal experiences)

Participation (interactive, self-involving and pro-active toward others)

Image Driven (driven by memory/heritage imagery)

Connected (ever changing connectedness)

In Sweets opinion the EPIC characteristics of the postmodern church are in contrast with four characteristics of the modern culture: (1) intellectual, (2) observational, (3) phrase/slogan driven and (4) myopic. Postmoderns are facing a new reality they have created (or that has created them) without the past which they have purposefully denied and excluded. Therefore, contextualization becomes a main factor in the churches ministry in order to give answers to the questions which postmoderns are asking in their search of identity. While the paradigm of the modern church has proven dysfunctional in postmodernity, Christianity must rediscover and relive the message of salvation as the answer for the present ever-changing reality.

In relation to my present context of ministry, Sweet’s proposal has a double side effect. In working with the Church of God in the United States, Postmodern Pilgrims is not only a description of the present situation in the average North American Christian church, but also a prophetic blueprint for the future development of its mission and ministry. As such creating an EPIC church makes sense as helpful and purposeful.

However, while relating the Postmodern Pilgrims to a Bulgarian Pentecostal audience, the EPIC church takes a more theoretical than practical form. Evangelical churches from the post-communist countries are still struggling with going through the age of modernism, where the sudden political changes and severe economical crises have created political, economical and spiritual chaos after the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Most interesting, however, is applying Sweet’s plan for postmodern pilgrimage in the Bulgarian evangelical churches in North America. In this context, typical post-communist, modern men and women are exposed to the postmodern North American culture. Both realities are combined to form a new reality – the reality of the immigrant. These people are left alone to perform the adaptation “jump” from modernity to postmodernity without actually having the chance to live through the transition process. In their context of ever-changing cultural adaptation, absolutes have very little meaning. Ministering to them, then, requires not simply words and managing techniques, but rather through Biblical spirituality which serves as roots replacing their missing past, as an identity for their ever-changing present reality and eschatological hope for both their future and eternity.

Pentecostalism and Postmodernity

Both Sweet and Johns approach postmodernity in a somewhat similar way. They see it as a process of denial of prior value systems which not only challenges present social systems, but also challenges one’s personal sense of identity. It is a reaction to the modernistic rationalism and to the concept that truth can be discovered through induction methodology. The most common concept of postmodernism is making everything relative. While postmoderns may not deny that there is truth, they question one’s ability to differentiate truth from non-truth. Postmodernity is about both loosing the old modern identity and finding a new postmodern one. As such, postmodernity calls for a search of a new, redefined identity for both the individual and the community as a whole. It is also about the opportunity for reinventing oneself; hence, postmoderns desire to constantly invent new identity. The new identity is rooted in a personal experience, rather than in the experience and model of others.

The difference in their views however comes with the application of the postmodernity in the Christian church. Of course, while Sweet writes about the Christian church as a whole (but focuses mainly on Western Christianity), Johns speaks specifically of the Pentecostal movement, its relationship to the postmodern culture, its roots and origin as a world view. In his customary style of writing, Sweet sounds like he is selling postmodernity to the church. He claims that the church must reconfigure its structure and ministry methodology in order to answer the new challenges. If the church fails to do this it is destined to eternal ministry failure in the era of postmodernity.

Sweet brings a number of conclusions based on current corporative management practices – a characteristic that has formed his writing/ lecturing style in the past several years. This distinguishes Postmodern Pilgrims from typical books about the Christian church. He consistently brings up facts, figures, statistics and analysis from corporative-industrial models to recommend the next step the church should make to assure its success in postmodernity. At times the book strongly resembles of the recent Bill Gates’ Business @ the Speed of Thought. Similar to what Bill Gates proposes to the management world, Sweet suggests that the church of postmodernity should adopt a somewhat virtual lifestyle to better understand and minister to the needs of the postmodern society.

On the contrary, Johns speaks of the church (Pentecostalism) as a movement that contains the characteristics of postmodernism long before postmodernism ever occurred. Differently than postmodernism, however, Pentecostalism is independent from any scientific paradigm and is not a worldview or structure, but rather a God-centered movement of believers. Thus, while Pentecostalism seems similar to postmodernity it not only occurs earlier in time, but carries a different set of characteristics and values.

Both Sweet and Johns come to the agreement in their conclusions that through reclaiming the past, the church of postmodernity, can remain in its original identity and give identity to others as well. Rooted in holiness the Christian church can provide an affective experience of God in the postmodern search for personal experience of reality.

Postmodern Rebels

In the beginning of the 20th century, Pentecostalism began as a rejection of the social structure which widely included sin, corruption and lack of holiness. These factors have spread not only in the society, but have established their strongholds in the church as well. Pentecostalism strongly opposed sin as a ruling factor in both the church and the community, seeing its roots in the approaching modernity. As a modern rebel, for a hundred years, Pentecostalism stood strongly in its roots of holiness and godliness, claiming that they are the foundation of any true Biblical church and community. Indeed, the model of rebelling against sin and unrighteousness was a paradigm set for the church by Jesus Christ Himself.

In the beginning of the 21st century, much is said about the church becoming a postmodern system serving the needs of postmodern people in an almost super-market manner. Yet, again, it seems reasonable to suggest that the Pentecostal paradigm from the beginning of modernity will work once again in postmodernity. While again moral values are rejected by the present social system, Pentecostalism must take a stand for its ground of holiness and become again a rebel – this time a Postmodern Rebel.

Pentecostalism and Post-Modern Social Transformation

Not by Might nor by Power is a work that provides a significant contribution to the process of developing Pentecostal theology and more specifically its social concern. This book deals extensively with the Latin America Child Care. Its structure is organized around issues concerning South American Pentecostals. This review will first offer a chapter-by-chapter overview of the book, second discuss several of the significant issues of the book, and third will show the book in the current context of ministry.

The book begins by establishing the foundation of Pentecostal faith and experience. The author uses the historical background of Pentecostalism connecting it with the story of the Latin American Pentecostal movement thus establishing the global transformative role of the movement.

Chapter two claims that through global transformation, Pentecostalism becomes a social relevant movement. The author examines this role of the movement within the current Latin American political and social context. A very important point is made about the parallel appearance of the Pentecostalism in different parts of the world, thus making the movement autonomous in each country where it was present. This development was possible only because Pentecostalism in its original North American context emerged among the poor and oppressed denying the authority of the rich and powerful and moving toward social liberation.

Chapters three and four deals with the compatibility of Latin American culture and Pentecostalism and is based on the topics discussed above. This way, chapter three is a paradigm merge between the topics dealt within chapters one and two. The Pentecostal characteristics are predominating in the discussion. Chapter four continues with the Pentecostal relevance to social processes and dynamics in Latin America. In this way of thought, the economical environment of Latin America is the factor that enables Pentecostals to participate in the social transformation. Chapter five brings a case study dealing with the Latin America Child Care. The LACC presents a paradigm for further society involvement, which is presented as the central proving point of the research.

There is a challenge for a better presentation of theology and praxis in chapters six and seven. The book claims the ability of Pentecostals to offer social action alternatives and calls for various forms of social expression which are developed based on coherent doctrinal statements. These include politics, eschatology, triumphalism and other important issues. In relation to the premillennial views of Pentecostalism, Petersen calls external critics to carefully reconsider the claim that Pentecostalism is purely dispensational. The book explains that in its very nature Pentecostalism and its view of the work of the Holy Spirit denies any limitations to the last, and at the same time proclaims the rapture of the church and the imminent return of the Lord. Thus Pentecostalism presents a unique already-not-yet eschatology which has served as a developmental factor of its social concern.

Concerning the relationship between Pentecostal eschatology and political involvement, Petersen critiques the purposeful abstinence of political involvement and viewing of politics as a rather worldly practice. The book urges Pentecostals to view politics as a tool for social involvement and transformation even in regard of the soon return of the Lord. In fact, the research seems to propose that political involvement is part of the eschatological expectation of the church.

Toward Context of Ministry Applications

While Latin America is quite separated from our present context of ministry in Bulgaria, Not by Might nor by Power presents many similarities between both, especially in the problematic issues of Pentecostal theology and praxis. Similarly to the problems in Latin America, in the beginning of the 21st century the Protestant Church in Bulgaria is entering a new constitutional era in the history of the country. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the political and economic challenges in Eastern Europe have strongly affected the Evangelical Churches. More than ever before, they are in need of reformation in doctrines and praxes in order to adjust to a style of worship liberated from the dictatorship of the communist regime. In order to guarantee the religious freedom for our young, democratic society, the Protestant Movement in Bulgaria needs a more dynamic representation. Such can be provided only by people who will create a balance between the old atheistic structures and the new contemporary, nontraditional style of ministry.

Similar is the case among Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in North America which also share analogue dynamics with congregations of Latin American immigrants. Several facts are obvious from such comparison. It is apparent that Bulgarian immigrants come to North America in ways similar as other immigrant groups. Large cities which are gateways for immigrants are probable to become a settlement for Bulgarian immigrants due to the availability of jobs, affordable lodging and other immigrants from the same ethnic group.

The emerging Bulgarian immigrant communities share religious similarities and belongingness which are factors helping to form the communities. As a result of this formation process, the Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in North America emerge. It also seems natural to suggest that as this process continues, Bulgarian Evangelical Churches will be formed in other gateway cities and other large cities which meet the requirements to become a gateway city. Such has been the case with Latin American churches. If this is true, it should be proposed that the Bulgarian Churches in North America follow a strategy for church planting and growth which targets these types of cities.

Pentecostalism and Post-Modern Social Transformation

Almost one hundred years ago, Pentecostalism began as a rejection of the social structure which widely included sin, corruption and lack of holiness. These factors had spread not only in the society, but had established their strongholds in the church as well. Pentecostalism strongly opposed sin as a ruling factor in both the church and the community, seeing its roots in the approaching modernity. As an antagonist to modernism, for almost a century Pentecostalism stood strongly in its roots of holiness and godliness, claiming that they are the foundation of any true Biblical church and community. Indeed, the model of rebelling against sin and unrighteousness was a paradigm set for the church by Jesus Christ Himself.

In the beginning of the 21st century, much is said about the church becoming a postmodern system serving the needs of postmodern people in an almost super-market manner. Yet, again, it seems reasonable to suggest that the Pentecostal paradigm from the beginning of modernity will work once again in postmodernity. While again moral values are rejected by the present social system, Pentecostalism must take a stand for its ground of holiness and become again a rebel – this time an antagonist to postmodern marginality and nominal Christianity or even becoming a Postmodern Rebel.

The Liberating Spirit

![9780802807281[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/97808028072811.jpg) The Liberating Spirit is an analytical examination of the Pentecostal movement in the Latino community. Pentecostalism is presented as a social transformation factor. The research is written for a scholarly audience, though it is understandable by the common believer as well. It argues for a “pneumatic” social ethic, and urges Pentecostals to move beyond selective preaching of salvation and to address such systemic issues as human rights, social injustice, racism, etc.

The Liberating Spirit is an analytical examination of the Pentecostal movement in the Latino community. Pentecostalism is presented as a social transformation factor. The research is written for a scholarly audience, though it is understandable by the common believer as well. It argues for a “pneumatic” social ethic, and urges Pentecostals to move beyond selective preaching of salvation and to address such systemic issues as human rights, social injustice, racism, etc.

The study follows a well developed structure which integrates Pentecostalism and social transformation within the context of a Hispanic American culture. Chapters one and two of the study deal with the Hispanic American culture through focusing on the Hispanic immigration in North America. Chapter three is an overview of the Hispanic Pentecostal reality to identify the Pentecostal church as a center for liberation from oppression in the context of Pentecostal eschatology. Chapter four provides Scriptural proof for the presented ideas, and chapter five concludes the research with a presentation of social ethic for the Hispanic American Pentecostals.

Pentecostal churches are presented as traditionally unlearned in their majority, but always open to the needs of the poor among them. Villafane even speaks of “menesteroso” (the oppressed) as a main focus of concern of the Pentecostal churches. Since its beginning the movement has emphasized the inclusiveness of the Christian community existing in the context of Christ’s love for all with special emphasis on the poor, suffering, sick and oppressed.

Being concern with all of these, Pentecostalism has viewed the pneumatic theology and praxis not only as a heritage of its ethos, but also as means through which social justice is made possible within the church and the world which the church reaches through ministry. In the pneumatic part of the research, the author responds to Karl Barth’s dream for theology of the Spirit. Villafane sees Pentecostalism as the movement that brings such theology.

In relationship to the immigration dynamics, the author gives an extensive overview of the Latin American immigrants and the way they experience their ethnic belongingness. Villafane shows that Latin American immigrants form at least four groups of language preferences (1) English only, (2) Bilingual with English preferences, (3) Bilingual with Spanish preferences and (4) Spanish only. This division is somewhat different than the Bulgarian language preference. At this present time, research shows that all Bulgarian immigrants speak some English but prefer Bulgarian among them. Also, all Bulgarian-born immigrants have studied Russian beside Bulgarian and English, but do not use it in their communication within or outside of the Bulgaria community. And finally, at this time there is no English only preference group among the Bulgarians. Perhaps such will be formed when a second generation of Bulgarian immigrants emerges in America.

Another interesting point of difference is the ethnos of the immigrant communities. Villafane shows that Latin American immigrants represent five such groups as follows:

- Mexicans 61%

- Puerto Ricans 15%

- Cubans 6%

- Central and South America 10%

- Other Nations 8%

The ethnic structure of the Bulgarian immigration in North America is close to the ethnic ratio in the Bulgarian nation which are: Bulgarians 80%, Turks 12%, Roma (6%) and others 2%. This presents several major differences between the Latin American and Bulgarian diasporas which are:

(1) The Latin American diaspora represents a much larger ethnic and geographical area from which immigrants have come than the Bulgarian one.

(2) The Latin American diaspora represents a much larger immigrant group in North America, with a longer history and large geographical location than the Bulgarian one.

(3) The Bulgarian diaspora represents a less defragmenter community as a large majority (80%) is Bulgarians. In the Latin American case almost 50% of the immigrants are with different ethnic background.

(4) The Bulgarian diaspora represents a different ethnic group, which differ not only by national belongingness, but by language as well.

In this context it must be critically noted that until recently cultural assimilation was considered an inevitable fact which can be prevented neither by the assimilating culture nor by the assimilated culture. It was considered that once a group of two or more cultures meet, assimilation begins. In America, however, assimilation is no longer seen as an inevitable process. Instead a cultural diversity exists in a rather mosaic structure described by the term “segmented assimilation.” Such phenomenal ethnic formation derives from the multiplicity of lifestyles and worldviews that formed a contemporary American culture. The technical term for this new mixing is “transnationalism.”

Villafane’s research further offers an in-depth overview of the Latin American communities in North America examining their culture and paradigms and influence of Pentecostal ministry among them. The text speaks of the “homo socius” or the person in the context of community, claiming that an individual is only a person when acting in the social context. A certain transformation from one social context to another is also suggested when viewed in cross-cultural dynamics of immigration, assimilation and naturalization. These processes are similar within the Bulgarian immigrant communities in North America in relation to the ministry of Protestant churches among them.

The Bulgarian Christian communities are searching for a model of adjustment to the assimilating culture in which they exist. This can be accomplished by adopting a strategy of incorporating the postmodern setting of worship, theology and praxis within the Bulgarian Christian community. It should be accompanied by an intentional process of liberation from the dysfunctional model through which the Bulgarian Protestant Church operated during the Communist Regime (1944-1989). This process should purpose to liberate the believers from an oppression mentality and transform them toward the mind of Christ, in order to minister effectively in the present context of existence. Failure to address this present dilemma will result in an inability of the Bulgarian Christian community to communicate its faith and to minister to the younger, faster-adjusting generation of Bulgarian-Americans, whose religious belongingness remains unexplored and often even unknown to themselves.

In all cases, the Bulgarian Evangelical churches accept the responsibility of being much more than a religious center, as it serves as a social and ethno-cultural center as well. Thus, in the context of ethic assimilation and cultural regrouping, the Bulgarian churches not only remain a protector of the Bulgarian ethnicity and the Bulgarian way of life, but also acts as an agent of cultural integration. Naturally, as such it has received the attention of Bulgarian immigrants who have altered it to meet present needs.

90 Years of Bulgarian Pentecostalism

Bulgarian Pentecostal believers celebrate 90 years of ministry and history. The Bulgarian Pentecostal movement is rooted in the Azusa street holiness Pentecostal revival which began in April of 1906. The revival then spread through the United States and less than a decade later, large Pentecostal denominations as the Church of God and the Assemblies of God were formed embracing the vision to send missionaries to foreign lands.

Bulgarian Pentecostal believers celebrate 90 years of ministry and history. The Bulgarian Pentecostal movement is rooted in the Azusa street holiness Pentecostal revival which began in April of 1906. The revival then spread through the United States and less than a decade later, large Pentecostal denominations as the Church of God and the Assemblies of God were formed embracing the vision to send missionaries to foreign lands.

After establishing contact with the World Missions Department of the Assemblies of God at the end of 1919, Cossack born immigrant, who later took on Ukrainian citizenship, Ivan Voronaev received a calling to return to his motherland and preach the message of Pentecost there. Alongside him traveled the family of Ukrainian immigrant Dionissey Zaplishny and his Bulgarian born wife Olga, who like Voronaev left the church they pastored in the United States to obey the call to missions.

On March 10, 1920, Assemblies of God issued Voronaev a certificate as a “pastor and evangelist in Bulgaria” valid till September 1, 1921 and on June 22, 1920 Voronaev notified them his plans to set sail for Russia with his family on July 13, 1920. On the said date, the Voronaev, Koltovitch and Zaplishny’s families set sail on the “Madonna” steamboat from New York to Constantinople. Along with them traveled a group of Kavkaz believers among which was Bulgarian Boris Klibok.

After arriving to Constantinople, they had to wait for visas to enter Russia. Voronaev immediately began meeting with the Russian community in town recognizing the lack of Russian Bibles and Pentecostal churches. He wrote on August 15, 1920: „ ….with the help of God opened Russian mission here [Constantinople], and God our work blessed;” and on August 30, 1920: „…. we had first baptism with water in river. I baptized one lady wife of a Russian office. Glory to Jesus!”

After waiting for three months in Constantinople, Voronaev arrived in the Bulgarian port city of Bourgas along with Bulgarian Boris Klibok. The Zaplishny family had already established their ministry there through Olga’s Congregational home church. What followed next was a revival that made history.

March 5, 1921: The Pentecostal Evangel published Voronaev’s report from Bulgaria where he has been holding Russian-Bulgarian revival services in various churches in the cities of Sliven, Yambol, Varna and Sofia. Seven received the baptism with the Holy Spirit.

April 16, 1921: The Pentecostal Evangel published Voronaev’s second report from Bulgaria about services in Sliven, Bourgas, Plovdiv and the Baptist Church in Stara Zagora where the daughter of the Baptist pastor from Kazanlak received the baptism with the Holy Spirit.

May 14, 1921: Services in the Congregational Church in Plovdiv and baptismal service in the Martiza River.

June 11, 1921: „In Bourgas, Bulgaria the Lord baptized with the Holy Spirit about fourteen souls. We have about twenty candidates for baptism with water, and about thousand Bulgarians and Russian were there and were much interested.”

July, 1921: The Latter Rain Evangel published an article under the title “Pentecost in Bulgaria” in which Voronaev wrote about new Pentecostal believers in seven Bulgarian cities, his relocation in Varna to work with the local Methodist church and his plan to move to Odessa. The Pentecostal Evangel from the same month wrote, “God called Brother J.W. Voronaeff, who had charge of a Russian Pentecostal Assembly in New York City, to Russia.”

The early Bulgarian Pentecostals spoke in other tongues, embraced the gifts of the Spirit, practiced foot washing and conservative holiness, and received the Bible as their rule of life almost to the point of ritualistic ascetism. It was their prayer, preaching and serving before the Lord that ensured the future of the movement. Many of them would be forced underground when the Pentecostal Union is registered with the Bulgarian State in 1928. Others will be persecuted even unto death during the Communist Regime after WWII. The more conservative group split right down the middle by two strong leaders, Tinchevists and Borisovtsi would protect the faith to the best of their abilities. Many modern religious formations, among which the Bulgarian Church of God, would spring out from these grassroots of these holiness seeking Pentecostal Puritans. By 1990, after the Berlin Wall had fallen, this group of people will go through the largest evangelistic revival in Bulgaria since the Christianization of Bulgaria in 861AD.