Diamonds in the Rough-N-Ready Pentecostal Series (2018)

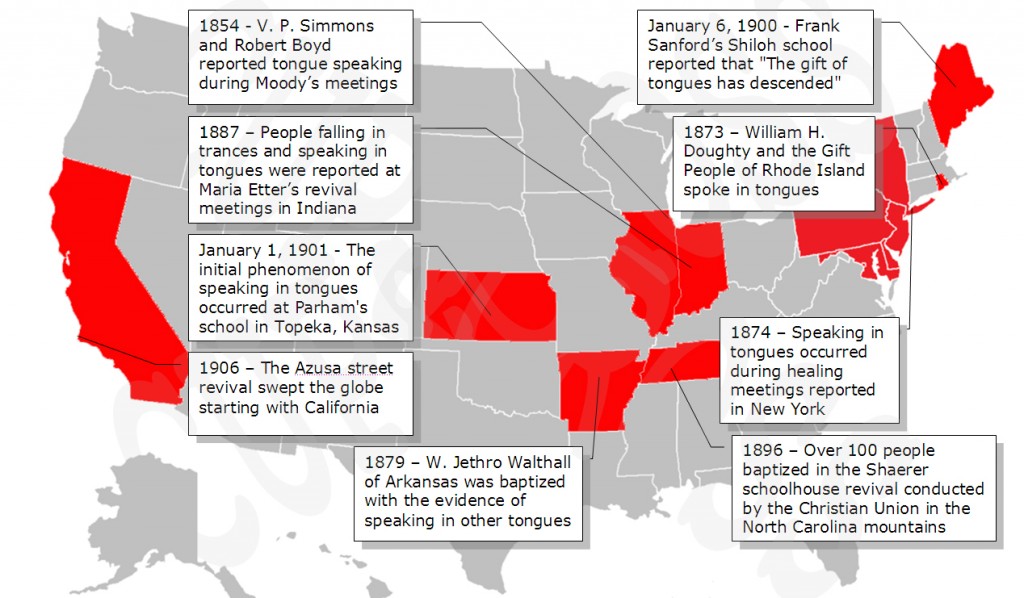

Speaking in Tongues in America Prior to the Azusa Street Revival of 1906

April, 1906 – The Azusa street revival swept the globe starting with California

January 1, 1901– The initial phenomenon of speaking in tongues occurred at Parham’s school in Topeka, Kansas

January 6, 1900 – Frank Sanford’s Shiloh school reported that “The gift of tongues has descended”

1896 – Over 100 people baptized in the Shaerer schoolhouse revival conducted by the Christian Union in the North Carolina mountains

1887 – People falling in trances and speaking in tongues were reported at Maria Etter’s revival meetings in Indiana

1874 – Speaking in tongues occurred during healing meetings reported in New York

1873 – William H. Doughty and the Gift People of Rhode Island spoke in tongues

1854 – V. P. Simmons and Robert Boyd reported tongue speaking during Moody’s meetings

FURTHER READING:

Church of God (Cleveland, TN)

- Alive, alive! (A personal testimony)

- Church of God Primitivism

- Bulgarian Church of God

- J.W. Buckalew

- Why revival came? by Dr. Charles Conn

Azusa Street Revival of 1906

- Lucy F. Farrow: The Forgotten Apostle of Azusa

- The FORGOTTEN ROOTS OF THE AZUSA STREET REVIVAL

- Azusa Street’s Apostolic Faith Renewed

- Azusa Street Sermons

- Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved

Prior to Azusa Street Revival of 1906

- First person to speak in tongues in the Assemblies of God was William Jethro Walthall of the Holiness Baptist Churches of Southwestern Arkansas

- The Work of the Spirit in Rhode Island (1874-75)

- Speaking in Tongues in America Prior to the Azusa Street Revival

- WAR ON THE SAINTS: Revival Dawn and the Baptism of the Spirit

- How Jezebel Killed One of the Greatest Revivals Ever

NEW Book – Sassy Southern Appalachian Mountain Cooking (Paperback) – Large Print

This cookbook includes 60 traditional Appalachian recipes with an emphasis on dishes of the southern mountainous regions. They are classic and basic recipes, but with a sassy southern flare of flavors.

This cookbook includes 60 traditional Appalachian recipes with an emphasis on dishes of the southern mountainous regions. They are classic and basic recipes, but with a sassy southern flare of flavors.

FREE Shipping on orders over $25

NEW Book – Tastes of Europe: 104 Traditional Recipes of Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Russia & More (Paperback)

Europe has a very rich history and is a place many aspire to visit. To walk its cobblestone streets, see the majesty of the Eiffel Tower or tour the ancient ruins of Rome are only but a few wondrous adventures one can partake in Europe. The tastes of Europe are all the same intriguing. European cuisine is filled with depths of flavor implementing fresh seasonal ingredients while being influenced by hundreds of different cultures and as many years of technique and mastery.

Europe has a very rich history and is a place many aspire to visit. To walk its cobblestone streets, see the majesty of the Eiffel Tower or tour the ancient ruins of Rome are only but a few wondrous adventures one can partake in Europe. The tastes of Europe are all the same intriguing. European cuisine is filled with depths of flavor implementing fresh seasonal ingredients while being influenced by hundreds of different cultures and as many years of technique and mastery.

Now you can enjoy this unique culinary culture of intriguing dishes from all over Europe right in the comfort of your own home. From the distinctive desserts of Czechoslovakian Blueberry Bublanina and Lithuanian Poppy Seed Cookies to the heavenly flavors of more traditional meals like Sautéed Sauerkraut with Pork and Mini Meatball Soup, Tastes of Europe includes delicious exciting recipes that are easy for all to prepare. This cookbook features 104 authentic recipes of Europe with an emphasis on Eastern European flavors and Bulgarian cuisine. Among other featured countries are France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Russia.

Some of these dishes are distant relatives to ones found in ancient Roman manuscripts believed to have been compiled in the late 4th or early 5th century AD. Others are among those far before the time of Christ. With nearly every dish comes a story and custom. This cookbook attempts to preserve these century year old stories for many years to come so they can continue to be passed down.

FREE Shipping on orders over $25

Pastor Nicholas Nikolov was born on March 15, 1900

In 2018, the Pentecostal Union in Bulgaria (Assemblies of God) is celebrating 90 years since its establishment. The story of the Pentecostal movement in Bulgaria is intrinsically connected with the life and ministry of Nicholas Nikolov. Pastor Nikolov was born in Bourgas, Bulgaria on March 15, 1900. His life story unfolds as following:

In 2018, the Pentecostal Union in Bulgaria (Assemblies of God) is celebrating 90 years since its establishment. The story of the Pentecostal movement in Bulgaria is intrinsically connected with the life and ministry of Nicholas Nikolov. Pastor Nikolov was born in Bourgas, Bulgaria on March 15, 1900. His life story unfolds as following:

- 1900 Born in Karnobat near Bourgas, Bulgaria

- 1914 Saved in the Congregational Church in Bourgas

- 1919 Under the ministry of Paul Mishkoff

- 1920 Attended university in New York

- 1921 Baptized with the Holy Spirit

- 1924 Married and working at Bethel

- 1926 Ordained and appointed by AG

- 1927 Led Pentecostal revival in Bourgas, Bulgaria

- 1928 Established the Pentecostal Union of Bulgaria (Assemblies of God)

- 1931 Returned to the States and earned a master’s degree

- 1935 Headed Assemblies of God training school in Gdansk, Poland

- 1938 Returned to Bulgaria after forced out of Poland by the Nazis

- 1939 Returned to the United States after forced out of Bulgaria by the Nazis

- 1941 President of Metropolitan Bible Institute

- 1947 Pastored in North Bergen, NJ

- 1950 President of New England Bible Institute

- 1952 Faculty at Central Bible Institute in Springfield, Missouri

- 1956 Earned a Ph.D. degree from the Biblical Seminary in New York

- 1961 Retired due to sickness

- 1964 Passed to Glory

A Church Assessment Can Change Your Church

March 10, 2018 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication, Research

Failure to thoroughly or consistently review aspects of the church will have a negative impact on the organisation in multiple ways. In contrast, when a church embraces an intentional review process there are a number of benefits:

Failure to thoroughly or consistently review aspects of the church will have a negative impact on the organisation in multiple ways. In contrast, when a church embraces an intentional review process there are a number of benefits:

1. An intentional church assessment process provides key information that can be catalytic for the growth of the church.

2. An intentional church assessment process ensures the church does not drift from its mission.

3. An intentional church assessment process uses the vision as motivation for change.

4. An intentional church assessment process protects the culture by ensuring it is not neglected in the busyness of activity.

5. An intentional church assessment process will identify when the systems or structure are no longer serving the vision.

6. An intentional church assessment process creates accountability for the achievement of strategic goals.

What You Need to Know About Culture in 2018

If it’s true that we put our money where our mouth is, then this report from Thenumbers.com will help you see how your favorite movies fared in 2017. There were over 700 movies that sold 1,197,554,799 tickets and grossed over $10 billion! Want to know the movies coming in 2018, here’s a calendar with the latest.

Who doesn’t love a good Ted Talk? Check out ted.com’s list of the top-14 Ted Talks in 2017.Megan Phelps-Roper describes life in Westboro Baptist Church, Tim Ferriss on why you should define your fears instead of your goals, Anjan Chatterjee on how your brain decides what’s beautiful…and much more here.

A new word added to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary this year is binge-watch. And these areNetflix’s top-10 binged shows in 2017. No, you don’t have to watch them but it’s a good idea to know what people are talking about when they mention dressing like 11 for Halloween. For more about the over 1,000 new words, read here.

And the words people googled en masse tell us much about what’s on their hearts and minds. Find out the top googled words here.

What You Need to Know About Technology in 2018

For the technophile, check out Time magazine’s top-10 gadgets that no respectable techno geek can be without. To learn more about gadgets you never even knew you needed, read more here.

The 10 most significant scientific discoveries of the year include editing a human embryo and a synthetic device to imitate a woman’s uterus.

And medical discoveries abounded in 2017. Read the Prevention.com list here and the Reader’s Digest list here.

What You Need to Know About Ministry in 2018

When you’re curious about what makes churches grow, check out Outreach Magazine’s top-100 list for insights into the fastest growing churches in America.

And while you’re at it, read the top-12 read articles on churchleaders.com to see what intrigued your peers and gave them ideas for more effective ministry.

Get in touch with what matters to the people you’re trying to reach with this list of demographic trends that affect them from Pew Research.

What You Need to Know About News in 2018

In case you missed it, here were the top-10 news stories in 2017. It was a stormy year! The weather outside was frightful and the boogey-man in Korea was blustery.

And news on the tech front features everything from Facebook to bitcoins. Read more here.

We all know a picture says a thousand words, but what about a political cartoon? These areUSAToday’s top 10.

What to Read if You Haven’t Yet in 2018

Here are just a few lists of the top books in 2017 from various sources.

CNBC: The 13 Best Business Books

Strategy-Business.com’s Top 3 Business Books

Desiringgod.org’s Top 17 Books of 2017

Thegospelcoalition’s best books from Kevin Deyoung

What You Need to Know About 2018

Getting ready for the coming year, check out…

The top-10 Social-Media Trends to Prepare for in 2018 from Entrepreneur.com.

And it looks like it’s going to be “more of the same” with the public agenda, according to a report from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Here’s to an amazing 2018! We at churchleaders.com are rooting for you and praying this will be a year that you experience God’s presence and blessings in everything.

2020 Vision for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches outside of Bulgaria

January 25, 2018 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication, Research

Over a decade ago, after publishing Bulgarian Churches in North America: Analytical Overview and Church Planting Proposal for Bulgarian American Congregations Considering Cultural, Economical and Leadership Dimensions, we purposed to explore the possibility of implementing the church planning program among Bulgarian Diasporas in various destination countries of migration.

Over a decade ago, after publishing Bulgarian Churches in North America: Analytical Overview and Church Planting Proposal for Bulgarian American Congregations Considering Cultural, Economical and Leadership Dimensions, we purposed to explore the possibility of implementing the church planning program among Bulgarian Diasporas in various destination countries of migration.

With this in mind, we carried the vision for establishing 20 Bulgarian churches outside of Bulgaria by the year 2020. Cyprus, the United Kingdom and Canada were among the first to successfully implement our program. Bulgarian migrant communities in France, Italy and especially Spain and Germany followed with great enthusiasm – there are 7 Bulgarian evangelical churches active in Span today, and 18 in Germany.

Of course, not all parts of the program proved to be efficient. The program’s modules and training that was implemented, however, have produced 47 strong church plants thus far and the number is growing every month. The program proposed has been confirmed by the leadership we have received from the Holy Spirit. Our commitment to seize the opportunity and work toward adding more Bulgarian churches by the year 202 has by far surpassed all expectations.

READ ALSO:

- Global Network of Bulgarian Evangelical Churches outside of Bulgaria (2018 Report)

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Restorative Significance of the Gifts Given to the Christ Child

It is recorded that the Magi gave the Christ Child three gifts upon his birth; gold, frankincense and myrrh. We understand the gold today as a physical gold, representing His kingship and the other two as an incense to symbolize his priestly role and oil for his foreseen death. Yet, what if the gold that was given to the Christ child was for another reason and perhaps it was not “gold”, but a golden spice or a golden salt. Of the gifts, one could be ingested, one could be inhaled and one could be absorbed. If we look at all from a medicinal viewpoint, these three gifts may have more symbolic meaning than once perceived.

It is recorded that the Magi gave the Christ Child three gifts upon his birth; gold, frankincense and myrrh. We understand the gold today as a physical gold, representing His kingship and the other two as an incense to symbolize his priestly role and oil for his foreseen death. Yet, what if the gold that was given to the Christ child was for another reason and perhaps it was not “gold”, but a golden spice or a golden salt. Of the gifts, one could be ingested, one could be inhaled and one could be absorbed. If we look at all from a medicinal viewpoint, these three gifts may have more symbolic meaning than once perceived.

MAGI

So who exactly were the “Magi”. We know that they followed the stars and were from the East. The East was a region of the world known, at the time, for its great knowledge of natural remedies. So it is not unimaginable that they could have been natural healers or homeopathic doctors of their times. This could explain the hypothesis that all three gifts had a therapeutic purpose in the life of Christ.

GOLD

If we view the gold in compound form, it can be used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Gold is a type of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic medicine (DMARD) that dampens down the underlying disease process. This meaning it treats inflammation and stops the immune system from attacking its own body’s tissue. Gold can also be used to treat other auto-immune conditions. If we think of the gift of gold as a spice, the first one that comes to mind is curcumin which is known as the “golden spice” of the East. It also has the ability to reduce inflammation and provides immune system support along with anti-cancer effects. This golden spice seems to have the ability to kill cancer cells and prevent their regrowth.

FRANKINCENSE

When frankincense is inhaled, it is the most effective method of delivery to send a chemical message to the brain. The oils in frankincense have a high level of sesquiterpenes, an agent found in plants that has the ability to go beyond the blood-brain barrier. Sesquiterpenes from frankincense increase oxygen availability in the limbic system of the brain which leads to an increase in secretions of antibodies, endorphins and neurotransmitters. In layman’s terms it has the ability to go straight to the brain without traveling through the bloodstream and brings healing properties to reset and repairs its internal communications. It’s almost as if it can unlearn a disease or degenerative disorder passed down in our DNA.

The amygdale glad of the brain’s limbic system plays a major role in storing and releasing emotional trauma. The only way to stimulate this gland is with fragrance or the sense of smell. This may help us understand how we are able to release emotional trauma with aromatherapy of frankincense.

MYRRH

Myrrh also can arouse the limbic system to release emotional trauma. It also has anti-inflammatory and immune boosting properties among with many other health benefits. Once applied to the body, oil molecules pass through dermis, into the capillaries and directly into the bloodstream.

The substance known as monoterpenes are present in almost all essential oils. They are what enhances the therapeutic values of other components and are the balancing portion of the oil. They inhibit the accumulation of toxins and restore the correct information in the DNA of the cell. Sesquiterpenes are also found in myrrh and delete the bad information in cellular memory or memories that are hypothesized to be stored outside the brain in the body.

REMARKS

This is quite interesting, to say the least, that all three gifts can protect the body from such dramatic trauma. The body of Christ from infancy was being safeguarded against what was to become his destiny of great suffering and pain. The cathartic releasing of emotional trauma provided with the gift of frankincense would lay the foundation for the harrowing experience of death by crucifixion.

All three offerings had anti-inflammatory properties and helped support the immune system by preventing the system from attacking its own body’s tissue. Christ’s earthly body was protected right down to the minuscule cellular level. Even the cellular memory of his body was restored with these gifts. At a molecular level, His Heavenly DNA was being guarded. The gifts purposed to protect the Christ child from disorders genetically passed down and to restore the information in the cells of the DNA.

One gift was for the body, one was for the blood and one was for the brain. One gift purposed to go beyond the blood-brain barrier while the other was via the bloodline. The Christ child was both a descendant of a Heavenly father and an early mother. The father’s bloodline was supernatural while the mothers’ was a physical line.

We will never truly understand this side of Heaven all the care that went into protecting the Christ child. Yet since we are descendants of a Perfect Deity, we too have this promise of complete restoration of curses, sickness, disease, imperfections, degenerative disorders, mental impairments, and any physical, mental or spiritual attack of the body, mind and soul. We have been given a choice of living a life of blessing or curse. Just as the gifts of the Christ child had to be accepted, we too much choose to accept this promise.

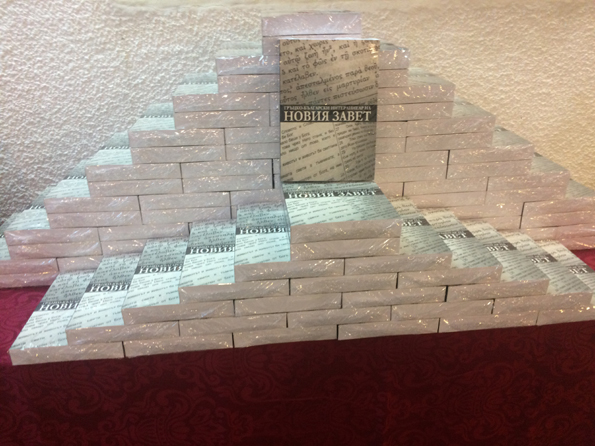

Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament Released on All Saints Day for the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation

Our decade long work of “Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament with Critical Apparatus Based on Nestle-Aland 27/28 and UBS-5” in Bulgaria is now released

After working on the New Bulgarian Translation of the Bible since 1996 and more actively on the interlinear version for the past decade, on October 31, 2017 for the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia on All Saints Day 2017, we presented hot off the press the first edition of the Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament from the critical edition of GNT.

On the picture, a symbolic stack of the first 95 copies arranged at the presentation to commemorate with the work of the great reformers.

Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament with Critical Apparatus: Addressed Problems and Proposed Solutions

Releasing our decade long work of “Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament with Critical Apparatus Based on Nestle-Aland 27/28 and UBS-5” in Bulgaria

After twenty some years in Bible translation and a decade long work on this current edition, we are happy to announce that on the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, our Greek-Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament will be presented in Bulgaria’s capital Sofia on All Saints Day 2017. The Greek Bulgarian Interlinear of the New Testament proposes the following solutions to the translation of the Bible in Bulgarian:

- A non-received test – Textus Haud Receptus

- Critical Edition of the Greek New Testament alike Revised Textus Receptus, Tischendorf, Westcott and Hort, von Soden, Nestle-Aland, UBS and SBL GNT

- Literal translation from Greek made word for word without dynamic equivalents

- Linguistic paradigm for repetitive parallel permutation structures in the Greek-Bulgarian translation alike form criticism of the Bible

- Analytical Greek New Testament with complete morphology of the words