Prophetic Presence: The Sign of the Seers

For many years now, as a student of both Pentecostal theology and history, I have always wondered of the ever-present desire for Pentecostals to associate themselves with physical addresses. It is indeed strange, for as a movement of the Spirit we have always strived to remain on the go, being always persecuted or ever-changing as people of God. So I am astounded every time I come across a historic attempt to redefine our identity with a place or a location.

For many years now, as a student of both Pentecostal theology and history, I have always wondered of the ever-present desire for Pentecostals to associate themselves with physical addresses. It is indeed strange, for as a movement of the Spirit we have always strived to remain on the go, being always persecuted or ever-changing as people of God. So I am astounded every time I come across a historic attempt to redefine our identity with a place or a location.

The examples are many. From the very inception of the term “spirit-filled” people on the day of Pentecost, we have always associated our experience with an attempting to restore the identity of and struggled to return to the spiritual context in the experience of the Upper Room – a definite location in the city of Jerusalem. Then Paul, before ever answering his apostolic call and entering what would turn to a global ministry, was instructed to go the street called “Straight” – and this was not just a personal experience of Paul, but a corporate calling that includes the prophetic gift of another man and affected the future of the Early Church as we know it.

The early Pentecostal revivalists are best known with the name of Azusa Street, but not before establishing various locations across the country setting a spiritual rout, a geographic walkabout from the Bethel Bible College to the Santa Fe Mission, reaching the small house at 214 North Bonnie Brae Street and the Azusa Street Methodist Mission by 1906.

Synan records that there: “They shouted three days and three nights. It was Easter season. The people came from everywhere. By the next morning there was no way of getting near the house. As people came in they would fall under God’s power; and the whole city was stirred. They shouted until the foundation of the house gave way, but no one was hurt.”

But it was not until the morning of April 18, 1906 that the prophetic presence of the Azusa Street Pentecostal revival received its full recognition. Once the Great San Francisco earthquake hit California, just as early Pentecostals had prophesied, there was no need for preaching or witnessing any longer. Their prophetic presence was evidence in full. For the assigned geographical location for our vision contributes little to our identity in the ministry. It is a prophetic sign for the people we witness to. And this is a Biblical principle.

John the Baptist associated his ministry with the desert. John the Apostle, with the island called Patmos. The Old Testament prophet laid on his side for 390 long days being seen by all. That is one long year and one whole month according to the Jewish calendar. Then 40 days more on his other side, just like the bodies of the two prophets will lay dead for the three days of Revelation. The Seers were there, seeing the future and proclaiming it to the present through nothing less than a prophetic presence. For the Seers must be seen in order to reveal the vision they have seen in the Spirit, in order that both the world and church blinded by sin, can see the vision of the unseen and invisible God.

Dony Donev: Theological Framework Centered on Neo-primitivism

Dony Donev’s theological framework is centered on neo-primitivism, which he describes as a return to the “basic order of the Primitive Church of the first century”. Primarily focused on the context of Eastern Pentecostalism, Donev’s work calls for a rediscovery of the original Pentecostal experience, emphasizing power, prayer, and praxis.

Coined terms and key concepts

Neo-primitivism: This is the central concept in Donev’s framework, which he coined in his book Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved. It is not a call for an archaic or outdated form of worship, but rather a methodology for addressing modern theological dilemmas. Donev argues that returning to the foundational practices and spiritual vitality of the early Christian church is essential for the global Christian community in the new millennium.

Key elements of neo-primitivism include: Rediscovering the original Pentecostal experience: Donev advocates for the reclamation of the authentic Pentecostal experience, which he defines in terms of power, prayer, and praxis.

Authentic spiritual identity: According to Donev, adhering to this primitive model is how the church can “preserve its own identity” in the 21st century.

Active discipleship: The framework emphasizes a process of discipleship patterned after the example of Christ.

Eastern Pentecostal Tradition

While not a coined term, Donev’s work is deeply rooted in and builds upon the unique history and theology of the Eastern Pentecostal Tradition. He draws heavily from his own Bulgarian background, highlighting the historical roots of Pentecostalism in Eastern Europe, as detailed in his book The Unforgotten: Historical and Theological Roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria.

Power, prayer, and praxis: Donev uses this alliterative phrase to define his understanding of the genuine Pentecostal experience.

- Power: Refers to the supernatural empowerment of the Holy Spirit.

- Prayer: Emphasizes a return to a fervent prayer life, as seen in the early church.

- Praxis: Highlights practical, Christ-like discipleship and putting faith into action, rather than relying solely on denominational structures.

Donev’s theological concerns

Donev developed his frameworks in response to what he saw as a crisis in the modern church, which he describes as facing “new existential dilemmas”. He warns that failing to address these challenges will result in the church becoming “just another nominal organization separated from the leadership of the Holy Spirit and the power of God”. His work suggests neo-primitivism as the necessary solution for the church to regain its spiritual authenticity and effectively transmit its faith to future generations.

The Practice of Corporate Holiness within the Communion Service of Bulgarian Pentecostals

by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals (Research presentation prepared for the Society of Pentecostal Studies, Seattle, 2013 – Lakeland, 2015, thesis in partial fulfillment of the degree of D. Phil., Trinity College)

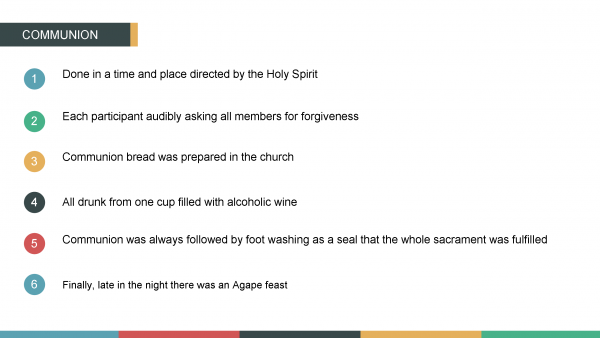

Pentecostal identity was corporately practiced and celebrated within the fellowship of believers through the partaking of Holy Communion. We have otherwise extensively described the Communion service among Bulgaria’s conservatives in Theology of the Persecuted Church (Part 1: Lord’s Supper https://cupandcross.com/theology-of-the-persecuted-church/). Therefore, here we offer just a brief overview of its main characteristics.

- It was done in a time and place directed by the Holy Spirit

- If some did not have water baptism they were taken to a close by river to be baptized while the rest of the church prayed

- Upon returning, if some did not have yet the baptism with the Holy Spirit, the church would pray until all were baptized

- It began with each participant audibly asking all members for forgiveness

- they would also audible respond with the words: WE FORGIVE YOU and may GOD also forgive you

- The communion bread was prepared on the spot baked by women whose names were also reveled in prayer

- All drank from one cup, which strangely for their strict practice of abstinence from alcohol, was filled with alcoholic wine

- Communion was served only to those who had the fullness of the Spirit, and had just requested and were given forgiveness

- The presbyter would quote Jude 20 to each partaking believer thus directing them to audibly speak in tongues before they could participate in communion

- Interpretation often followed to confirm the spiritual stand of the believer

- If there were any leftovers, the Communion elements were served again until all was used

- Communion was incomplete without foot washing as a seal that the whole sacrament was fulfilled.

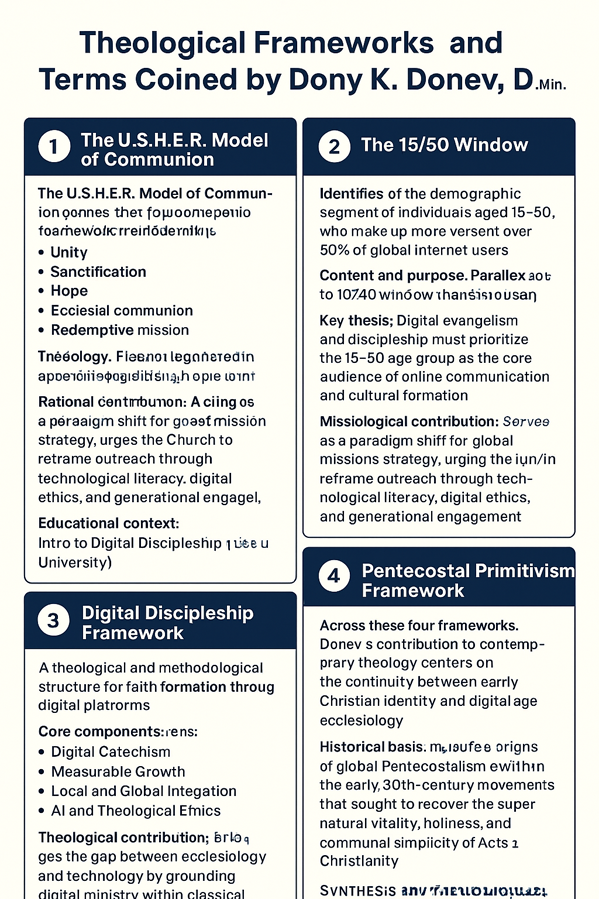

Theological Frameworks and Terms by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

Theological Frameworks and Terms Coined by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

1. The U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion

Definition: The U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion is a theological framework defining what follows Communion within the Christian catechism. It was formulated by Dony K. Donev, D.Min., during the Covid-19 Pandemic as part of his Intro to Digital Discipleship course at Lee University.

Etymology and Structure: “U.S.H.E.R.” functions as an acronym representing five theological dynamics foundational to post-Communion discipleship:

-

Unity – Communion establishes and sustains the unity of believers within the Body of Christ.

-

Sanctification – The sacred act reaffirms the believer’s ongoing transformation and holiness.

-

Hope – The eschatological anticipation of Christ’s return is renewed through participation.

-

Ecclesial Communion – The act strengthens the Church’s shared identity as one community of faith.

-

Redemptive Mission – The table leads outward into the missional call of proclaiming redemption to the world.

Theological Contribution: Donev’s model reframes the Eucharist not as a terminal ritual but as a launching point for continued Christian formation and mission. It synthesizes sacramental theology with discipleship praxis, emphasizing that the mystery of Communion initiates lived transformation beyond the table.

2. The 15/50 Window

Definition: Coined by Dony K. Donev, D.Min., the 15/50 Window identifies the demographic segment of individuals aged 15 to 50, who collectively represent over 50% of global internet users.

Context and Purpose: In parallel to the 10/40 Window—the geographical missions concept popularized in late 20th-century missiology—Donev’s 15/50 Window transitions the focus from spatial geography to digital demography.

Key Thesis: Digital evangelism and discipleship must prioritize the 15–50 age group as the core audience of online communication and cultural formation, representing the “digital mission field” of the 21st century.

Missiological Contribution: The 15/50 Window serves as a paradigm shift for global missions strategy, urging the Church to reframe outreach through technological literacy, digital ethics, and generational engagement. It integrates sociological data with practical theology, redefining the boundaries of mission fields in a connected world.

3. Digital Discipleship Framework

Definition: Developed by Donev within his academic teaching and research, the Digital Discipleship Framework proposes a theological and methodological structure for faith formation through digital platforms.

Definition: Developed by Donev within his academic teaching and research, the Digital Discipleship Framework proposes a theological and methodological structure for faith formation through digital platforms.

Core Components:

-

Digital Catechism: Translating traditional doctrinal instruction into digital environments.

-

Measurable Growth: Employing data-informed tools to track discipleship outcomes online.

-

Local and Global Integration: Linking local church identity with global digital engagement.

-

AI and Theological Ethics: Evaluating the theological implications of artificial intelligence in spiritual education.

Theological Contribution: Donev’s work bridges the gap between ecclesiology and technology by grounding digital ministry within classical discipleship principles. It argues that digital formation is not a substitute for embodied community but an extension of the Church’s incarnational mission into virtual contexts.

Educational Context: Initially articulated in Intro to Digital Discipleship (Lee University), this framework has influenced contemporary pedagogical approaches to online ministry training and has served as a foundation for AI-integrated theological education.

4. Pentecostal Primitivism Framework

Definition: The Pentecostal Primitivism Framework is a theological model developed by Dony K. Donev, D.Min., describing the historical and doctrinal identity of Pentecostalism as a restorationist return to the spiritual and communal life of the early (primitive) Church.

Definition: The Pentecostal Primitivism Framework is a theological model developed by Dony K. Donev, D.Min., describing the historical and doctrinal identity of Pentecostalism as a restorationist return to the spiritual and communal life of the early (primitive) Church.

Historical Basis: Donev situates the origins of global Pentecostalism within the early 20th-century movements that sought to recover the supernatural vitality, holiness, and communal simplicity of Acts 2 Christianity.

Key Features:

-

Restoration of Apostolic Practice: Reclaiming New Testament models of ministry, healing, and charismatic gifts.

-

Eschatological Urgency: Interpreting Pentecostal mission through the lens of imminent eschatology.

-

Communal Purity: Emphasis on holiness, shared life, and ethical distinctiveness.

-

Missionary Zeal: Evangelistic energy rooted in a return to primitive apostolic mandate.

Theological Contribution: The framework provides a systematic lens for analyzing Pentecostal identity as both renewal and return—a dynamic that transcends denominational boundaries. Donev’s articulation of Pentecostal Primitivism contributes to Pentecostal studies by clarifying the movement’s theological self-understanding and its missiological implications in global Christianity.

Synthesis and Theological Significance

Across these four frameworks, Donev’s contribution to contemporary theology centers on the continuity between early Christian identity and digital-age ecclesiology.

His work consistently integrates:

-

Historical Pentecostal roots (Pentecostal Primitivism),

-

Missiological expansion (15/50 Window),

-

Digital ecclesial formation (Digital Discipleship), and

-

Sacramental praxis leading to mission (U.S.H.E.R. Model).

Together, they represent a coherent theological corpus that bridges primitive Christian spirituality with postmodern digital theology, providing a constructive path for future ecclesial engagement and academic inquiry.

Standing Firm in the Bible Belt Responding to a Resurgence of Witchcraft

Patricia Crowther passed away in September 2025 at the age of 97 from complications related to dementia. Crowther was one of the last direct cult-initiate of Gerald Gardner, often called the “father” of modern Wicca. For the past 75 years followers of Gardnerian Wicca have distorted truths teaching their beliefs as a spiritual path of reclamation, healing, and reverence for nature.

With her death, many adherents of modern paganism and witchcraft have felt motivated to interpret her passing as a moment of transitional resurgence. Her widespread hold has influenced new seekers and fringe groups to draw inspiration from her work, especially in places where spiritual vacuum or dissatisfaction with organized religion is strong.

In the rural parts of the Bible Belt like Tennessee, this phenomenon has posed particular challenges such as the following:

- Spiritual vulnerability: Some in isolated or economically struggling areas may be more open to alternative spiritualities if they feel the established church has failed them.

- Cultural tensions: Witchcraft or occult practices can intensify spiritual conflict, foster anxiety about “demonic influence,” or create fear and division in close communities.

- Distraction from the work of the Gospel: If congregations become preoccupied with spiritual warfare or defensive postures, that may drain resources from evangelism, discipleship, social outreach, and community care.

Thus, this death, rather than closing a chapter, may galvanize increased activity among her followers and deepen the spiritual battleground in regions already steeped in Christian faith. Prayer, fasting and standing firm with His light is the only force that will prevail against the darkness.

The Land of Pentecostals

A brief Interaction with Walter Brueggemann

by Dr. Dony K. Donev

Since I began studying Pentecostal history sometime ago, I have pondered the question of space and how we, Pentecostals, associate with it. Perhaps, on a larger scale, all Christian associate with space and location, but for Pentecostals it somehow becomes part of the identity of a given event, process or even person. This association is so strong that we simply cannot tell our history without it. And how is one even expected to tell Pentecostal history without places like the Bethel School of Healing, 214 Bonnie Brie Street and the Azusa Street Mission? Or how are we supposed to tell our story, to give our testimony of events significant and central for our spiritual life without a place and a location, which in most cases defines them all? For example, our salvation is connected the place where we were saved and sanctified; baptism with water or with fire from above; healing on the spot at a given prayer meeting, miracle service or church revival. And even eschatology, always undividable from the meeting in the clouds and the Heavenly city.

For Pentecostals, the Full Gospel teaching is a covenant theology because it ultimately subscribes to the quest for the Promised Land. But, I’ve never been able to pin point the reasoning behind this until reviewing anew Brueggemann’s study of “The Land” and comparing his ideas with Pentecostal history and praxis through the following quotes that will exchange perspectives with the questions stated above and hopefully stir further thinking.

p.5 “Space” means an arena of freedom without coercion or accountability, free of pressure and void of authority. …. But “place” is a very different matter. Place is space which has historical meanings, where some things have happened which are now remembered and which provide continuity across generations. Place is space in which important words have been exchanged, which have established identity, defined vocation, and envisioned destiny. Place is space in which vows have been exchanged, promises have been made, and demands have been issued. Place is indeed a protest against unpromising pursuit of space. It is a declaration that our humanness cannot be found in escape, detachment, absence of commitment, and undefined freedom.

Whereas pursuit of space may be a flight from history, a yearning for a place is a decision to enter history with an identifiable people in an identifiable pilgrimage.”

p. 11 “The very land that promised to create space for human joy and freedom became the very source of dehumanizing exploitation and oppression. Land was indeed a problem for Israel. Time after time, Israel saw the land of promise become the land of problem.”

p. 15 “….land theology in the Bible: presuming upon the land and being expelled from it; trusting toward a land not yet possessed, but empowered by anticipation of it.”

p. 27 “The action is in the land promised, not in the land possessed … So Jacob, bearer of the promise, is buried in Canaan under promise.”

p. 42 “Presence is for pursuit of the promise …. The new people, contrasted with the old, are promise-trusters, rooted in Moses, linked to the faith of Caleb, and identified as the vulnerable ones. His presence is evident in his intervention not to keep things going, but to bring life out of death, to call to himself promise-trusters in the midst of promise-doubters.”

p. 47 “Israel knew that in his speaking and Israel’s hearing was its life. That is why the first word in Israel’s life is “listen” (Deut. 6:4)! Israel lived by a people-creating word spoken by this people-creator (Deut. 8:3).”

p. 51 “Both rain and manna come from heaven, from outside the history of coercion and demand.”

p. 53 “Israel does not have many resources with which to resist the temptation. The chief one is memory. At the boundary [of Gilgal] Israel is urged to remember …. Remembering is an historic activity. To practice it is to affirm one’s historicity.”

p. 54 “Land can be a place for historical remembering, for action that affirms the abrasive historicity of our existence. But land can also be, as Deuteronomy saw so clearly, the enemy of memory, the destroyer of historical precariousness. The central temptation of the land for Israel is that Israel will cease to remember and settle for how it is and imagine not only that it was always so but it will always be so. Guaranteed security dulls the memory …. Israel’s central temptation is to forget and so cease to be a historical people, open either to the Lord of history or to his blessings yet to be given. Settled into an eternally guaranteed situation, one securely knows that one is indeed addressed by the voice of history who gives gifts and makes claims. And if one is not addressed, then one does not need to answer. And if one does not answer, then one is free not to care, not decide, not to hope and not to celebrate.”

p. 56 “The land will be avenged preciously because land is not given over to any human agent, but is a sign and function in covenant. Thus arrayed against the monarchy are both the traditionalism of Naboth and the purpose of Yahweh.”

p. 57 “Israel finds itself in history as one who had no right to exist. Slaves become an historical community. Sojourners become secured in land …. Non of it achieved, all of it given …. And the way to sustain gifted existence is to stay singularly with the gift-giver.”

And the following conclusions: as Pentecostals, we associate with places and location, we ultimately associate with land as part of our covenant theology, because:

1. In the land we place our own historical meaning, our part and role in history, as well as the spiritual heritage we have received and we give to a next generation; thus, place itself becomes not only where our history happens, but a defining part of our historical identity as a people.

2. Enduring the promise of a land not yet seen, but already received by faith, has indeed been the formative factor in any and all Pentecostal movements around the globe, as well as the initiative to restore the social order for peoples whose land has been taken away unfairly. We have even learned, that when the Promised Land becomes a land of problem, we must return to the promise in order to remain a movement after the move of the Holy Ghost and not merely a nominal denomination.

3. As humans, we localize the omnipresence of God to the place of our experience with God – the place where God has become personal for us. And this is the place, where we dare say, we have received the promise of God. Although His promise may not yet be visible in reality, having come from our experience with God, it creates a reality which is much more real than the present reality. In that sense, the very act of receiving the promise that comes from outside of history and through hearing the voice of God, recreates our reality and future.

4. Main, among other temptations for us, is the temptation to forget the land, the place of promise and meeting with God – where we come from, where we have been and where we are going. Just as Israel, this act of forgetting denotes our ceasing from being a historical people.

5. And just like Israel did, Pentecostals find themselves without the right to exist. Yet, the association with the land, and not merely any land but the Land of Promise, gives us not only a right of existence, but also an identity which no one, not even us, can change or redefine, except the Giver of the Promise. And this is the function of the covenant and the association of our personal experience with God to a place, a location, a spot in history where our lives were once and for all changed for eternity.

A Call for Righteousness over Orthodoxy