Bulgaria: New Interim Government Ahead of Early Elections

President Iliana Yotova has formally nominated Andrey Gyurov, Deputy Governor of the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB), as Bulgaria’s caretaker Prime Minister. The handover of the caretaker government mandate is scheduled for Thursday, February 12, at 10:00 a.m., when Yotova will meet Gyurov at the presidency and task him with forming an interim cabinet under Article 99, paragraph 5 of the Constitution. Gyurov is one of five senior civil servants who had indicated their willingness to take on the caretaker prime minister role during presidential consultations, alongside Deputy Ombudswoman Maria Filipova, Audit Board Chair Dimitar Glavchev, and his deputies Margarita Nikolova and Silvia Kadreva.

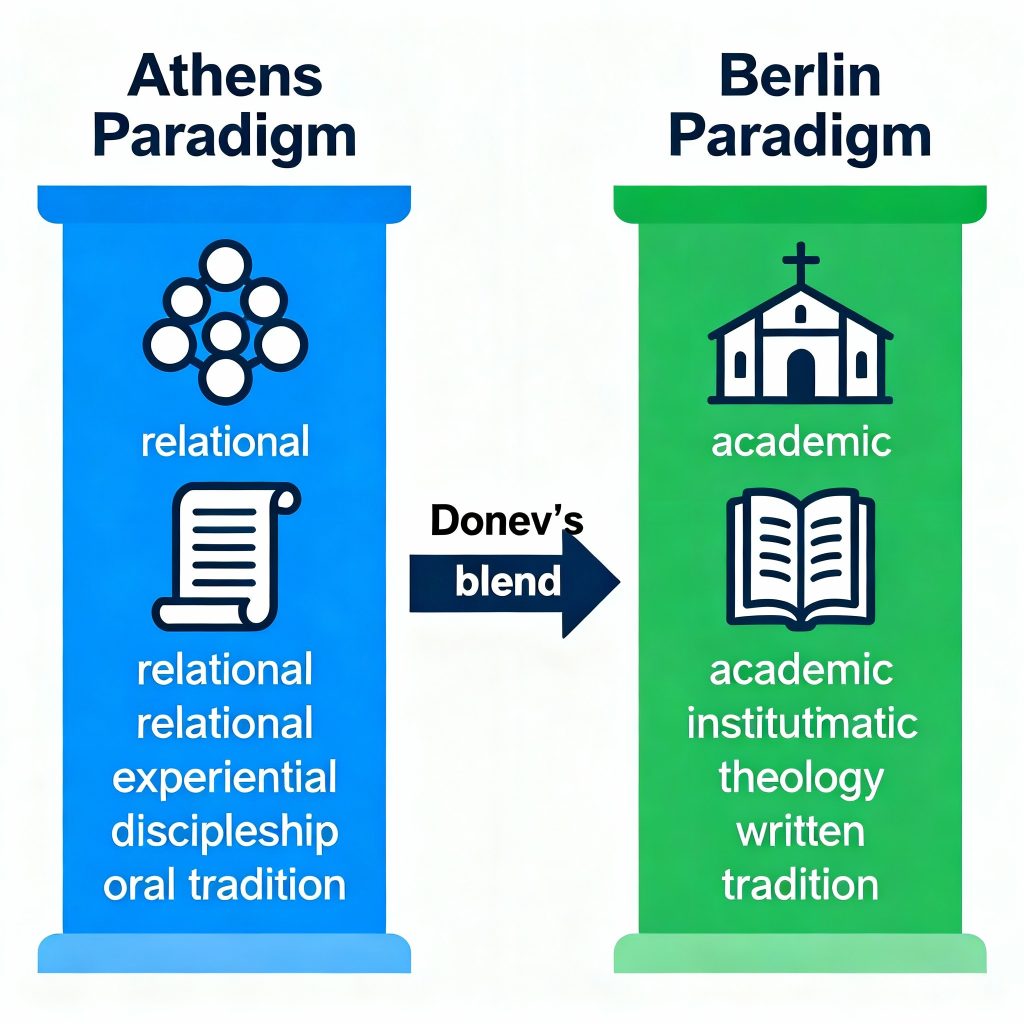

Frameworks and Key Terms by Dr. Dony Donev: Athens vs Berlin Paradigm Shift

Core Theological Frameworks

U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion

A theological framework coined during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Donev’s Intro to Digital Discipleship course at Lee University. It defines what follows Communion in Christian catechism, identifying five foundational dynamics for disciple growth: Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, and Redemptive mission.

Freedom Theology (Theology of Freedom)

Developed through Donev’s research on postcommunist Eastern Europe and the Bulgarian Protestant experience, this framework explores biblical concepts of freedom, liberation from both sin and socio-political oppression, and the church’s transformative mission as a liberator in history. It often appears in his writings as “Feast of Freedom,” drawing connections between national liberation and spiritual renewal.

Primitive Church Restorationist Model

Based in his historical research, Donev advocates for returning to the original practices and structure of the Early (Primitive) Church. This model emphasizes rediscovering authentic spiritual identity, intergenerational faith transmission, and revivalist community rooted in biblical precedent.

These frameworks have had meaningful impact on global Pentecostal studies, digital discipleship, and liberation theology, addressing contemporary challenges in theology, worship, and ecclesial practice.

Effect on Donev’s Models

-

U.S.H.E.R. Model: By anchoring his post-Communion framework in the “Athens” paradigm, Donev prioritizes unity, lived discipleship, and communal mission over purely doctrinal or institutional forms. This perspective shapes the model to valorize shared spiritual experience and relational growth, not just catechetical instruction.

-

Freedom Theology: “Athens” influences Donev’s liberation emphasis by grounding freedom in communal lived reality, while “Berlin” marks the shift toward codifying and structurally analyzing liberation.

-

Primitive Church Restoration: Donev navigates between Athens’ restorationist, dialogical church identity and Berlin’s historical-critical, analytical methodology, advocating an integration that revitalizes spiritual community while acknowledging scholarly insights.

In sum, Donev’s “Athens vs Berlin” usage intentionally blends experiential, relational Christian practice (“Athens”) with disciplined, systematic theology (“Berlin”). This dynamic underlies his frameworks, ensuring they are both deeply incarnational and critically constructive.

2026 Proclamation

Judgment has come to this region!

We were given six years to repent and to change our ways, yet we did not heed the call. We did not hear because we were distracted listening to false reports, following false gods, and walking false paths. Because of this, hardship has come upon us, and greater trials still lie ahead.

What we experienced since the Pandemic has been difficult, but what is coming will resemble the trials of Job. Only those who possess the faith of Job, those who remain steadfast and faithful, will emerge victorious on the other side. Only those who stop complaining and start moving toward conquering the promise will take the land. Only those who believe in the report of the One who brought you out of bondage will receive the blessing of milk and honey.

It does not matter that the enemy is bigger. It does not matter that their army is greater. It does not matter that there is no water or food. He is our provision and will not forsake us even though we feel as if we have been striped down to nothingness.

Stand your ground. Stand tall against demonic works in this region to which we have foolishly opened the door in our weakness. Find your backbone.

Claim your babies, claim your family, claim your promise.

Do not yield to the enemy. Not even one centimeter. Don’t even flinch in fear.

The anxiety and fear you are encountering is a lie from the pits of hell. Rebuke them in the name of Jesus.

BUT if we continue to look the other way, if we continue to welcome sin into our homes and into our sanctuaries, refusing to call sin what it is, then there will be NO hope. There will be no promise of protection. Hypocrisy will not be excused. Grace is not a license for rebellion.

Turning the house of worship into a smoke-and-mirrors spectacle is shameful. The sanctuary must remain holy. It should be a place so sacred, so charged with the presence of God, that one feels conviction even standing upon its floor. A place where no one would dare treat it casually by sipping on their starbucks. No distractions, no performances, no self-promotion.

The church can no longer function as a social club designed to entertain or accommodate the sinful, New Age practices that have crept into our region. Idolatry is wrong. Overlooking that gods have been drowned in our rivers is not acceptable. Bowing in a yoga stance to the gods is wrong.

Playing with magic is wrong. Communicating with the dead is not a game. It is wrong, even if it is your blood dabbling with it. We are to hate the sin, but love the sinner, but this does not mean to turn a blind eye to the manipulation of witchcraft and homosexuality.

Holiness is not optional! It is the standard. Period. Judgment has come to this region. Repent, repent, repent.

ENTER 2026…

A Message from Dr. David Griffis

These are very dark days in America, dear reader, and indeed this infection of evil is spreading throughout the globe. As a Christian and student of God’s Holy Word, I have been awakened to speak to you, for I hear in my spirit, the distant thunder of tribulation, deception, and evil increasing.

I am appalled at much of the silence in the world of denominational Christendom, about all that is taking place. I understand and weep at the deliberate soft stepping in this hour by religious leadership, afraid to offend, fearing how their needed words might affect their own future, but if ever an hour needed the voice of God’s true prophets it is now.

Believe me when I speak now, I speak broken and humbly, for I feel unworthy to carry His message…but God will not let truth be silent.

This whole thing, exploding in America , is a spiritual warfare issue. Remember how the Prophet Daniel was told by the Angel Gabriel, that his answer to prayer was delayed by a demonic power known as the “Prince of Persia” (Daniel10:13) and Michael the Archangel had to come and defeat this demon before Daniel’s answer from God came.

And the Apostle Paul’s Ephesians declaration in Ephesians 6 warns us of “principalities and powers”, which are satanic rulers who have taken influence over areas of earth that have given themselves to evil.

What is going on, in not only Minneapolis, but in large cities throughout America, and indeed many cities of the world, is a satanically inspired spiritual warfare, with hatred spewing like molten volcanic lava, with fear rolling like a deep earthquake caused tsunami, and violence erupting, as demonic forces from the deepest pits of hell, where demon spirits writhe and rule, filling hearts opening to receive such dominion.

But we Christians should sing the song dear reader, to the entire world in the midst of all this chaos, the song that has the answer….the answer is true, and O, so needed….

“What can wash away my sin?

Nothing but the blood of Jesus.

What can make me whole again?

Nothing but the blood of Jesus.

O, Precious is the flow,

That makes me white as snow.

No other fount I know,

Nothing but the blood of Jesus!”

We sing the song extolling the power of Jesus’s blood, and His redemptive power. God has a work in progress, that the enemies control of the news media does not want you to hear.

There is a satanic attempt to stop the last day spread of the Gospel out of the United States, as a “New Christian Conservatism” is developing in this country that could be the impetus for the final Joel 2:28 fulfillment. Charlie Kirk was in the forefront of this movement, when an assassin, with a transgender lover, goaded by hell itself, put a bullet through Charlie’s neck.

But God’s work is never dependent on just one person, and though Charlie’s life was taken, God’s work through many different channels, but especially in local churches anointed by God, with anointed shepherds leading them, remains. The last day harvest is coming in, I see it everywhere I go.

The devil is doing everything in his power to try and stop this move of God among our young people. So “principalities and powers” create the chaos in major cities like Minneapolis, and lure young people seeking for answers into the fray of hatred.

Violence and mayhem, do not come from The Good Shepherd. Hatred of authority does not come from God. Something evil is amiss when “law and order” is hated as an enemy. If lawmen do wrong, their own judgement will come. All, and I mean all, must live with their deeds.

So what must happen?

God will, as the Prophet declared, “pour His Spirit out upon all flesh”, while at the same time there is, as Saint Paul warns us, “a great falling away”.(II Thessalonians 2:3)

What Christians must do to combat this onslaught of calculated evil…

Voice the truth and flee the posture of silence embraced by so many “Leading Christians”. But declare the word of the Lord only as the Spirit leads you, for God alone knows the time of His speaking

Find your “Closet of Intercession”. That closet is of utmost importance .

Seek guidance from the Word of God, for this is vital to spiritual survival, and for some strange reason I have been led in my awakening from the wee hours of the morning to commend to you for your reading and meditation, the books of Proverbs, Habakkuk, John, Ephesians, both First and Second Timothy, and the Book of Jude, and any others God may lay upon your heart.

Find people of like precious faith and form bonds of prayer and sharing of testimonies. We must be united as Christians.

Look not to “Christian flamboyant, celebrity personalities” as your source….they are falling one by one…Nor should you trust in the carnality that is found in “professional denominational political leaders” in these dangerous times.

But rather, listen to the humble voice of the true shepherds of God’s flock, the “apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors and teachers” that Ephesians 4:11 refers to, who will lead you not toward themselves, but toward Christ. For God has placed them here for His purposes. And remember, no true messenger from God, will ever say anything that contradicts God’s Holy Word.

I have finished now and have delivered what He has given me dear reader…please take heed.

ENTER 2026…

37 Years after Communism…

The Fall of the Berlin Wall was on the evening of November 9, 1989

37 years in 60 seconds at the red-light…

I’m driving slowly in the dark and raining streets of my home town passing through clouds of car smoke. The gypsy ghetto in the outskirts of town is covered with the fog of fires made out of old tires burning in the yards. And the loud music adds that grotesque and gothic nuance to the whole picture with poorly clothed children dancing around the burnings.

The first red light stops me at the entrance to the “more civilized” part of the city. The bright counter right next to it slowly moves through the long 60 seconds while tiredly walking people pass through the intersection to go home and escape the cold rain. The street ahead of me is already covered with dirt and thickening layer of sleet.

This is how I remember Bulgaria of my youth and it seems like nothing has changed in the past 30 years.

The newly elected government just announced its coalition cabinet – next to a dozen like it that had failed in the past two decades. The gas price is holding firmly at $6/gal. and the price of electricity just increased by 10%, while the harsh winter is already knocking at the doors of poor Bulgarian households. A major bank is in collapse threatening to take down the national banking system and create a new crisis much like in Greece. These are the same factors that caused Bulgaria’s major inflation in 1993 and then hyperinflation in 1996-97.

What’s next? Another winter and again a hard one!

Ex-secret police agents are in all three of the coalition parties forming the current government. The ultra nationalistic party called “ATTACK” and the Muslim ethnic minorities party DPS are out for now, but awaiting their move as opposition in the future parliament. At the same time, the new-old prime minister (now in his second term) is already calling for yet another early parliamentarian election in the summer. This is only months after the previous elections in October, 2014 and two years after the ones before them on May 2013.

Every Bulgarian government in the past 30 years has focused on two rather mechanical goals: cardinal socio-economical reforms and battle against communism. The latter is simply unachievable without deep reformative change within the Bulgarian post-communist mentality. The purpose of any reform should be to do exactly that. Instead, what is always changing is the outwardness of the country. The change is only mechanical, but never organic within the country’s heart.

Bulgaria’s mechanical reforms in the past quarter of a century have proven to be only conditional, but never improving the conditions of living. The wellbeing of the individual and the pursuit of happiness, thou much spoken about, are never reached for they never start with the desire to change within the person. For this reason, millions of Bulgarians and their children today work abroad, pursuing another life for another generation.

The stop light in front of me turns green bidding the question where to go next. Every Bulgarian today must make a choice! Or we’ll be still here at the red light in another 37 years from now…

ENTER 2026…

Yotova Becomes Bulgaria’s First Female President

The Constitutional Court of Bulgaria has formally accepted President Rumen Radev’s resignation, paving the way for Vice President Iliana Yotova to assume the presidency. Pavlina Panova, president of the Constitutional Court, served as rapporteur on the case. With the court’s unanimous decision, effective January 23, 2026, Yotova becomes Bulgaria’s first female head of state. Twelve constitutional judges participated in the session, which confirmed that Radev’s resignation was made voluntarily and without external pressure. As this is not an impeachment case, no additional hearings or investigations were required.

Following the court ruling, Radev’s presidential powers are officially transferred to Yotova. She will not need to retake the oath before the National Assembly, having already sworn in as vice president in 2021. Later today, at 4 p.m., Radev will leave the presidential building through the ceremonial entrance, accompanied by Yotova, marking the conclusion of his nine-year tenure. Social media initiatives have already begun commemorating his departure. Expectations are high that Radev will soon announce his own political project ahead of the upcoming early elections.

Rumen Radev, a Major General in the Air Force and former Commander of the Air Force, was first elected president in November 2016. He took office on January 22, 2017, alongside Iliana Yotova as vice president. The pair were re-elected in November 2021 for a second term. Notably, Radev is the first president in Bulgaria’s democratic history to resign before completing a term, leaving Yotova to finish their second term alone.

Peace Council: only Bulgaria & Hungary from EU

The US president is currently announcing the ‘Peace Council.’ This involves the creation of a new international body called the ‘Board/Peace Council’ (in public discourse it has become known as the ‘Peace Council’ or ‘Board of Peace’), which is presented as a tool for peacemaking—initially focusing on Gaza—but will gradually expand as a ‘crisis management’ forum for other conflicts as well.

What the ‘Peace Council’ is – and why it raises suspicion

According to Reuters, Trump has sent invitations to around 60 countries, aiming for a body that ‘starts with Gaza’ and ‘expands’ to other fronts, while the same report mentions that permanent participation is expected for those who pay $1 billion and that Trump will be chairman for life.

The existence of a ‘ticket’ for a permanent seat (and at an amount that functions as a power filter rather than an equal contribution) is the first major source of European distrust: it turns the body into a closed club, favoring the ‘willing’ and the financially powerful, rather than a process of legitimacy through international treaties.

The second source of distrust is the political structure: in a Reuters report about Italy, it is mentioned that Rome considers participation in an organization ‘led solely by the U.S. president’ to be in conflict with the Italian constitutional principle requiring equal participation in international organizations. Italy’s argument encapsulates European concern: the ‘Council’ does not resemble a multilateral institution but rather a mechanism of American hegemony, where access, duration, and renewal of tenure (according to what has leaked about the draft charter) are directly linked to the central will of the U.S. president.

The third problem is institutional overlap. In a television excerpt/transcript from CNN (Situation Room), the ‘peace council’ already appears as a point of tension between Trump and Macron, with Trump escalating rhetoric and using trade threats in a domain that would ‘normally’ belong to diplomacy and collective security. This combination of ‘hard power’ (tariffs) with ‘peacemaking architecture’ (board) is the main warning sign for Brussels: it turns peacemaking into a tool of coercion.

Greece absent, as is the rest of the EU, except Hungary and Bulgaria

In Greek reporting, Athens appears aligned with general European reluctance. This is a strategic choice: due to geography and sovereignty issues, Greece has historically invested in strict adherence to International Law and the UN institutional framework.

This logic also underpins the statement by government spokesperson Pavlos Marinakis regarding Greenland—that ‘we cannot play with issues of International Law.’

At the same time, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis ultimately misses Davos because his flight to Zurich was canceled due to severe weather, resulting in a cut program since he had to immediately travel to Brussels for the EU emergency summit.

Bulgaria’s President Steps Down to Run in Upcoming Elections

In a landmark address to the nation, President Rumen Radev announced that he will resign from his post before the Constitutional Court in order to participate in the upcoming elections.

Further reading: Who Is Iliyana Yotova: Bulgaria’s First Female President

For weeks, speculation has swirled about the president’s potential resignation and plans to lead a political project in the elections. Last month, Radev told the press that he would reveal a political initiative when society least expected it.

Further reading: Bulgaria After the President’s Resignation: What Comes Next Politically and Institutionally?

Collapse of the Western Theological Corpus: Conquistadorial Colonial Theology Toward the Global South is Over

Bridges to people and culture do not work any longer because they never touch the water of troubled cross-cultural issues. For the same reason, contextual theology does not work any more – once faced with the deep cross-cultural crises of faith and conviction, it sinks with no hope.

We have long observed the collapse of the “Western Theological Corpus,” as Andrew Walls calls the structural problem in missions today. Main reason for its collapse is the failure to give answers to the theological questions emerging from the Global South. As a result, the colonial approach of doing missions, resonating in imperialistic cross-cultural ministry and ethnic conquest for assimilation of cultures, all have failed both the indigenous people and the mission sending agencies. Prayer has hence turned into a protest and prophecy for a new reality, where the encounter of missions is no less than the very cross-roads where we encounter God and others together.

Doing Missions in the Spirit in 2018

2026

In 2019, the Spirit nudged me to the understanding that by 2026, the idea of pandemic will be exhausted. The mentality of those who endure the crises will be permanently changed. Artificial Intelligence will form a new subculture for those open to be influenced.

For those who have remained outside of the system, off the grid, as sovereign citizens or similar, it will be difficult to participate in society. There is no hiding from the star of one’s “true identity” with constant biometric monitoring virtually everywhere. Christians are the minority now.

By 2027, if the Lord terries, our world as we knew it will be nonexistent if we do not firmly stand against the demonic warfare that is so ever present. We are battling a force which is so great it influenced angels to fall from Heaven and caused God’s chosen people to turn from His protection.

The Good News is that God always some way sends a warning to his people if they will only

take heed and listen. He is a loving God full of kindness, but there is no room for demonic works in His Kingdom.

I will not stand by quietly and allow any born or unborn child to be sacrificed. Our sons and daughters will not pass through any fire. They will not be offered as any burnt offering. I declare that my children will be the ones to prophesy and to see beyond worldly understandings.

Will you accept the call and take a stand against evil; to declare that you will not tolerate sorcery or magic or divination or witchcraft or any demonic confusion in any way?

Read more here: A CALL