The Forgotten Etowah Revival

By 1907 Church of God overseer AJ Tomlinson was well aware of the Etowah outpowering going on in parallel with the Azusa Revival. He also used the Etowah L&N many times during his travels. But chose Cleveland (on the famous Copper Road route), because Cleveland had not seen revival just yet. And this was about to change soon…

Bradley County, Cleveland, Tennessee was the western terminus of the Copper Road where copper ore from Ducktown and Copperhill was brought by wagons to the East Tennessee & Georgia RR. It was completed to Cleveland from Dalton, Georgia in 1851. In 1905 the Southern Railway hired New York architect Don Barber to design what became known as “Terminal Station” of the Chattanooga Choo-Choo, which in parallel to the Etowah L&N Depot began construction in 1907 and opened in 1909. So, no, the choice Tomlinson made was not obvious at all, neither it was based on the train line per se. He did not want to compete with the Etowah and Chattanooga revivals, and settled for Cleveland instead…

The Forgotten Etowah Revival

The Forgotten Etowah Revival

It started with the Old-Line Railroad quickly built in 1890 as part of a project to link Knoxville, TN to Marietta, GA by rail. Just a few short years afterwards, a distinctive feature was built as part of the line, the Hiwassee Loop, a circle of track that was built around Bald Mountain. The story told that when the workers came down from the mountain to build the L&N line and depot to connect the Hiwassee River Rail Loop, there wasn’t much to do except work. On the weekend, many of them flooded the old Methodist church across from today’s Etowah‘s chamber of commerce, mainly to look for women (as old timers plainly put it). А holiness preacher was carrying on a revival there, many were convicted under the power of the Holy Spirit and got saved.

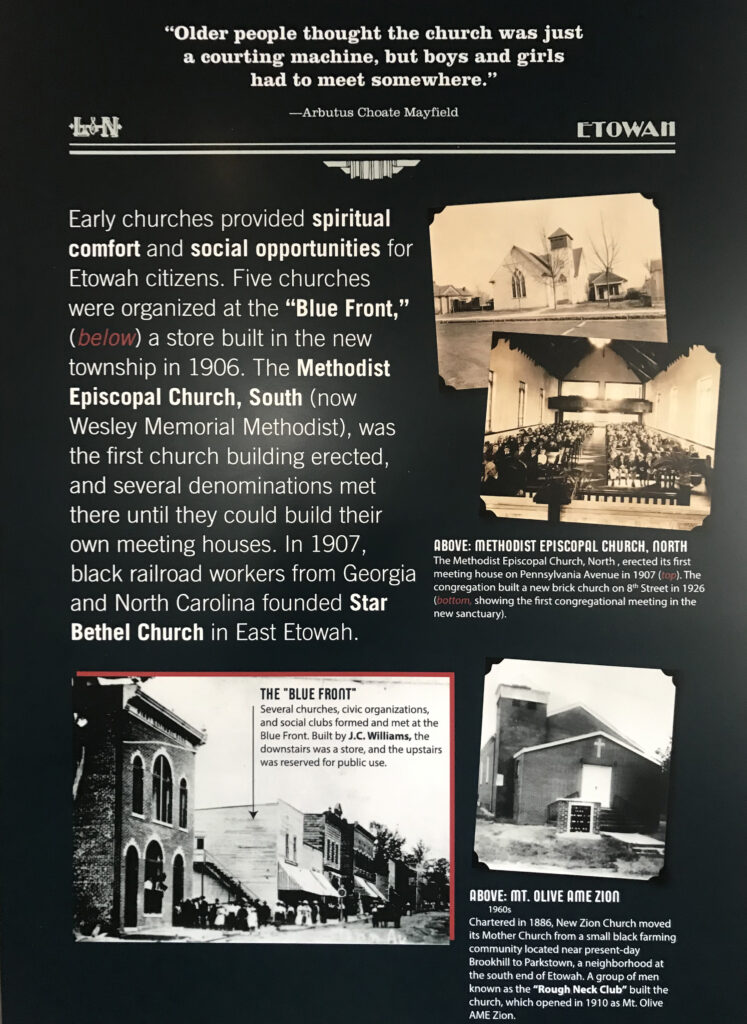

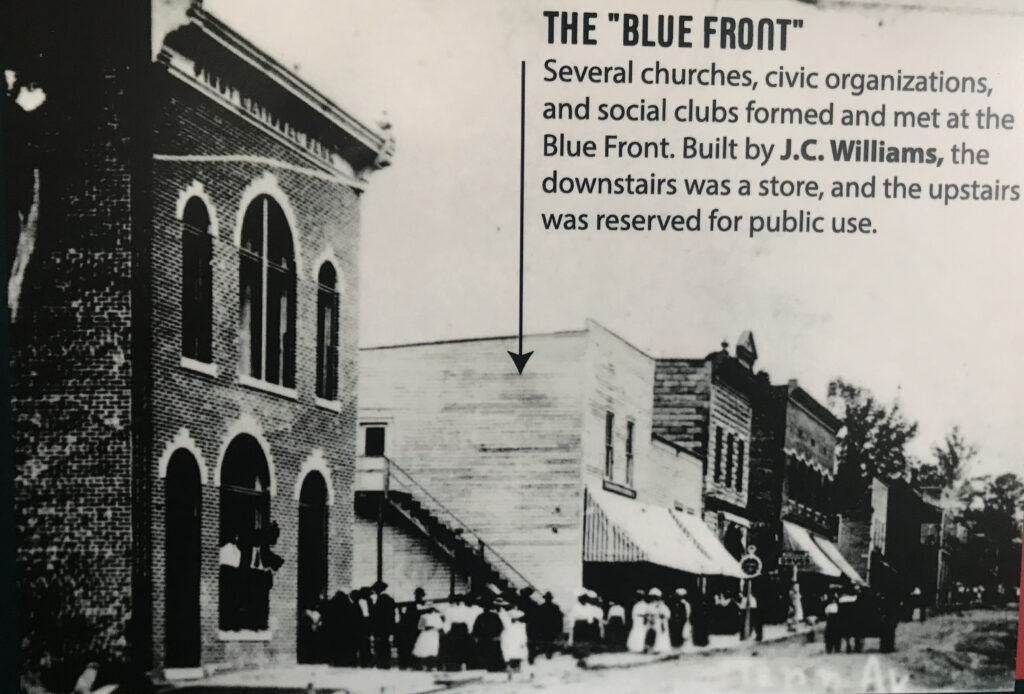

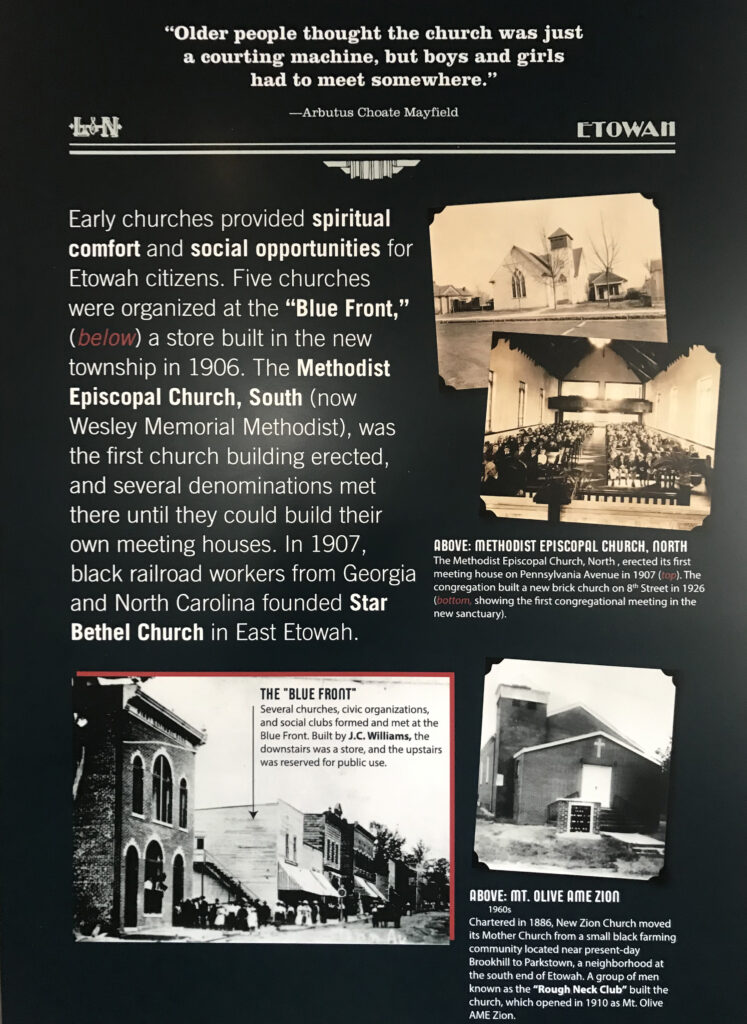

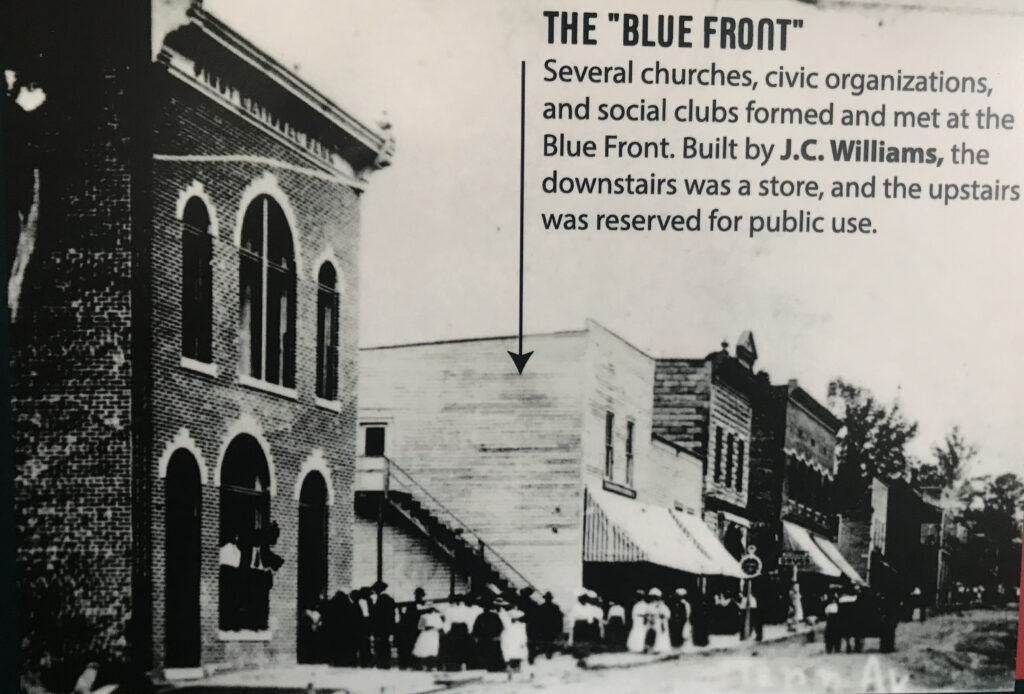

Those were the years of ongoing holiness revivals across Appalachia. Out West, the Pentecostal revival at Azusa was already brewing. Much like the rest of the holiness outpourings, the Etowah revival swept through the area. Not just workers, but the local population was touched as well. The upper room at “Blue Front” built by J.C. Williams built in 1906, where revival meetings were held, became the starting point of at least five local congregations.

At the same time, the Church of God movement was gaining speed on the other side of the mountain. Murphy, Tellico Plains and Reliance all became sites of the first holiness Spirit outpourings. In just a short amount of time, the Church of God grew and moved down the trainline to Cleveland, TN. Interestingly enough, most of the trainline was built along old confederate routes, which followed the Trail of Tears.

The Tellico Blockhouse was the starting point for the Old Federal Road, which connected Knoxville to Cherokee settlements in Georgia. The route ran from Niles Ferry on the Little Tennessee River near the present-day U.S. Highway 411 Bridge, southward into Georgia. Starting from the Niles Ferry Crossing of the Little Tennessee River, near the U.S. Highway 411 bridge, the road went straight to a point about two miles east of the present town of Madisonville, Tennessee. This location is 20 some miles north of the Tellico Plains area that marks the site of the beginning of the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee). The road continued southward via the Federal Trail connecting to the North Old Tellico Highway past the present site of Coltharp School, intersected Tennessee Highway 68 for a short distance and passed the site of the Nonaberg Church. East of Englewood, Tennessee it continued on the east side of McMinn Central High School and crossed Highway 411 near the railroad overpass. Along the west side of Etowah, the road continued near Cog Hill and the Hiwassee River near the mouth of Conasauga Creek where there was a ferry near the site of the John Hildebrand Mill. From the ferry on the Hiwassee River the road ran through the site of the present Benton, Tennessee courthouse. It continued on Welcome Valley Road and then crossed the Ocoee River at the Hildebrand Landing. From this point the road ran south and crossed U.S. Highway 64 where once stood the River Hills Church of God (Ocoee Church of God).

Revival Continues

In 2023, over a dozen of churches from the greater Conasauga, Reliance, Ocoee, Old Fort, Benton, and Delano communities along with the two oldest Polk County congregations at Cookson Creek and Friendship Baptist, joined piece by piece the original revival vision God has given to many ministers for this area of East Tennessee. While a few saw it as a spiritual connection with the brief spark of the Lee University student revival earlier in the year, most were convinced it was the restoration movement of the original Appalachian/Cherokee holiness outpouring, which took place among L&N Depot and Hiwassee River Rail Loop workers in the old Methodist church at the “Blue Front” across from Etowah‘s chamber of commerce. In 2023, the Polk Co. Revival began in September and carried on well through the fall until Thanksgiving. This year, even more churches in the area are praying again for a fresh outpouring of the Spirit expecting another revival to sweep the hearts of many in the area where no more than a century ago, the Early Revival Rain fell in abundance.

The Forgotten Etowah Revival

By 1907 Church of God overseer AJ Tomlinson was well aware of the Etowah outpowering going on in parallel with the Azusa Revival. He also used the Etowah L&N many times during his travels. But chose Cleveland (on the famous Copper Road route), because Cleveland had not seen revival just yet. And this was about to change soon…

Bradley County, Cleveland, Tennessee was the western terminus of the Copper Road where copper ore from Ducktown and Copperhill was brought by wagons to the East Tennessee & Georgia RR. It was completed to Cleveland from Dalton, Georgia in 1851. In 1905 the Southern Railway hired New York architect Don Barber to design what became known as “Terminal Station” of the Chattanooga Choo-Choo, which in parallel to the Etowah L&N Depot began construction in 1907 and opened in 1909. So, no, the choice Tomlinson made was not obvious at all, neither it was based on the train line per se. He did not want to compete with the Etowah and Chattanooga revivals, and settled for Cleveland instead…

The Forgotten Etowah Revival

The Forgotten Etowah Revival

It started with the Old-Line Railroad quickly built in 1890 as part of a project to link Knoxville, TN to Marietta, GA by rail. Just a few short years afterwards, a distinctive feature was built as part of the line, the Hiwassee Loop, a circle of track that was built around Bald Mountain. The story told that when the workers came down from the mountain to build the L&N line and depot to connect the Hiwassee River Rail Loop, there wasn’t much to do except work. On the weekend, many of them flooded the old Methodist church across from today’s Etowah‘s chamber of commerce, mainly to look for women (as old timers plainly put it). А holiness preacher was carrying on a revival there, many were convicted under the power of the Holy Spirit and got saved.

Those were the years of ongoing holiness revivals across Appalachia. Out West, the Pentecostal revival at Azusa was already brewing. Much like the rest of the holiness outpourings, the Etowah revival swept through the area. Not just workers, but the local population was touched as well. The upper room at “Blue Front” built by J.C. Williams built in 1906, where revival meetings were held, became the starting point of at least five local congregations.

At the same time, the Church of God movement was gaining speed on the other side of the mountain. Murphy, Tellico Plains and Reliance all became sites of the first holiness Spirit outpourings. In just a short amount of time, the Church of God grew and moved down the trainline to Cleveland, TN. Interestingly enough, most of the trainline was built along old confederate routes, which followed the Trail of Tears.

The Tellico Blockhouse was the starting point for the Old Federal Road, which connected Knoxville to Cherokee settlements in Georgia. The route ran from Niles Ferry on the Little Tennessee River near the present-day U.S. Highway 411 Bridge, southward into Georgia. Starting from the Niles Ferry Crossing of the Little Tennessee River, near the U.S. Highway 411 bridge, the road went straight to a point about two miles east of the present town of Madisonville, Tennessee. This location is 20 some miles north of the Tellico Plains area that marks the site of the beginning of the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee). The road continued southward via the Federal Trail connecting to the North Old Tellico Highway past the present site of Coltharp School, intersected Tennessee Highway 68 for a short distance and passed the site of the Nonaberg Church. East of Englewood, Tennessee it continued on the east side of McMinn Central High School and crossed Highway 411 near the railroad overpass. Along the west side of Etowah, the road continued near Cog Hill and the Hiwassee River near the mouth of Conasauga Creek where there was a ferry near the site of the John Hildebrand Mill. From the ferry on the Hiwassee River the road ran through the site of the present Benton, Tennessee courthouse. It continued on Welcome Valley Road and then crossed the Ocoee River at the Hildebrand Landing. From this point the road ran south and crossed U.S. Highway 64 where once stood the River Hills Church of God (Ocoee Church of God).

Revival Continues

In 2023, over a dozen of churches from the greater Conasauga, Reliance, Ocoee, Old Fort, Benton, and Delano communities along with the two oldest Polk County congregations at Cookson Creek and Friendship Baptist, joined piece by piece the original revival vision God has given to many ministers for this area of East Tennessee. While a few saw it as a spiritual connection with the brief spark of the Lee University student revival earlier in the year, most were convinced it was the restoration movement of the original Appalachian/Cherokee holiness outpouring, which took place among L&N Depot and Hiwassee River Rail Loop workers in the old Methodist church at the “Blue Front” across from Etowah‘s chamber of commerce. In 2023, the Polk Co. Revival began in September and carried on well through the fall until Thanksgiving. This year, even more churches in the area are praying again for a fresh outpouring of the Spirit expecting another revival to sweep the hearts of many in the area where no more than a century ago, the Early Revival Rain fell in abundance.

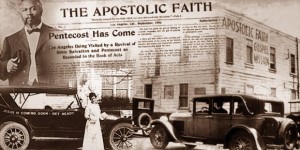

The Forgotten Azusa Street Mission: The Place where the First Pentecostals Met

For years, the building on Azusa Street has also been an enigma. Most people are familiar with the same three or four photographs that have been published and republished through the years. They show a rectangular, boxy, wood frame structure that was 40 feet by 60 feet and desperately in need of repair. Seymour began his meetings in the Mission on April 15, 1906. A work crew set up a pulpit made from a wooden box used for shipping shoes from the manufacturer to stores. The pulpit sat in the center of the room. A piece of cotton cloth covered its top. Osterberg built an altar with donated lumber that ran between two chairs. Space was left open for seekers. Bartleman sketched seating as nothing more than a few long planks set on nail kegs and a ragtag collection of old chairs.

What the new sources have revealed about the Mission, however, is fascinating. The people worshiped on the ground level — a dirt floor, on which straw and sawdust were scattered. The walls were never finished, but the people whitewashed the rough-cut lumber. Near the door hung a mailbox into which tithes and offerings were placed since they did not take offerings at the Mission. A sign greeted visitors with vivid green letters. It read “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin” (Daniel 5:25, kjv), with its Ns written backwards and its Ss upside down. Men hung their hats on exposed overhead rafters where a single row of incandescent lights ran the length of the room.

These sources also reveal that the atmosphere within this crude building — without insulation or air conditioning, and teeming with perspiring bodies — was rank at best. As one writer put it, “It was necessary to stick one’s nose under the benches to get a breath of air.”

Several announced that the meetings were plagued by flies. “Swarms of flies,” wrote one reporter, “attracted by the vitiated atmosphere, buzzed throughout the room, and it was a continual fight for protection.”

A series of maps drawn by the Sanborn Insurance Company give a clear picture of the neighborhood. The 1888 map discloses that Azusa Street was originally Old Second Street. The street was never more than one block in length. It ended at a street paving company with piles of coal, along with heavy equipment. A small house, marked on the map by a “D” for domicile, sat on the front of the property with the address of 87. (See highlighted section.) A marble works business specializing in tombstones stood on the southeast corner of Azusa Street and San Pedro. Orange and grapefruit orchards surrounded the property. On the right of the map a Southern Pacific railroad spur is clearly visible. The City Directory indicates that the neighborhood was predominantly Jewish, though other names were mixed among them.

A second map of the property was published in 1894. Old Second Street had become Azusa Street, and the address had been changed to 312. The house had been moved further back on the property where it served as a parsonage. The dominant building at 312 Azusa Street was the Stevens African Methodist Episcopal Church. At the front of the building a series of tiny parallel lines on the map mark a staircase that stood at the north end of the building providing entry to the second floor, the original sanctuary.

The only known photograph of the church from this period shows three interesting features. First, it shows the original staircase. Second, and less obvious, the original roofline had a steep pitch. Third, three gothic style windows with tracery lines adorned the front wall.

By 1894, the citrus groves had largely disappeared. On the southern side they were replaced by lawn. The smell of orange blossoms and the serenity of the orchard were rapidly being replaced by the banging of railroad cars and the smell of new lumber. A growing number of boarding houses and small businesses, including canneries and laundries, were moving into the immediate area by this time. The property marked “YARD” on the map is the beginning of the lumberyard that soon came to dominate the area. The City Directory reveals fewer Jewish names, and more racial and ethnic diversity in the neighborhood, including African Americans, Germans, Scandinavians, and Japanese.

Stevens AME Church occupied the building at 312 Azusa Street until February 1904 when the congregation dedicated a new brick facility at the corner of 8th and Towne and changed their name to First AME Church. Before the congregation could decide what to do with the property on Azusa Street, however, an arsonist set the vacant church building on fire. The structure was greatly weakened, and the roof was completely destroyed. The congregation decided to turn the building into a tenement house. They subdivided the former second-floor sanctuary into several rooms separated by a long hallway that ran the length of the building. The stairs were removed from the front of the building and a rear stairwell was constructed, leaving the original entry hanging in space. The lower level was used to house horses and to store building supplies, including lumber and nails.

In 1906, a new Sanborn Map was published. (See 1906 map.) The building was marked with the words “Lodgings 2nd, Hall 1st, CHEAP.” The transition of the neighborhood had continued. The marble work still occupied the southeast corner of Azusa Street and San Pedro, but a livery and feed supply store now dominated the northeast corner. A growing lumberyard to the south and east of the property now replaced the once sprawling lawn. A Southern Pacific railroad spur curved through the lumberyard to service this business.

The Apostolic Faith, the newspaper of the Azusa Street Mission between September 1906 and June 1908, later referred to the nearby Russian community. Many of these recent immigrants were employed in the lumberyard. They were not Russian Orthodox Christians as one might guess; they were Molokans — “Milk drinkers.” This group had been influenced by some of the 16th-century Reformers. They did not accept the dairy fasts of the Orthodox Church. They were Trinitarians who strongly believed in the ongoing guidance of the Holy Spirit. Demos Shakarian, grandfather of the founder of Full Gospel Business Men’s International, was among these immigrants who were led to Los Angeles through a prophetic word given in 1855.

Henry McGowan, later an Assemblies of God pastor in Pasadena, was a member of the Holiness Church at the time. He was employed as a teamster. He timed his arrival at the nearby lumberyard so he could visit the Mission during its afternoon services.

This map suggests why some viewed the Mission as being in a slum. A better description would be an area of developing light industry.

In April 1906, when the people who had been meeting at the house at 214 North Bonnie Brae Street were forced to move, they found the building at 312 Azusa Street was for sale. The photograph below taken about the time that the congregation chose to move into the building shows the “For Sale” sign posted high on the east wall of the building, as well as the rear of the tombstone shop. Seymour, pastor of the Azusa Street Mission, and a few trusted friends met with the pastor of First AME Church and negotiated a lease for $8 a month.

An early photograph reveals what the 1906 version of the map indicates. The pitched roof had not been replaced. The building had a flat roof. The staircase that had stood at the front of the building had been removed.

In a sense, this building suited the Azusa Street faithful. They were not accustomed to luxury. They were willing to meet in the stable portion of the building. The upstairs could be used for prayer rooms, church offices, and a home for Pastor Seymour.

Articles of incorporation were filed with the state of California on March 9, 1907, and amended May 19, 1914. The church negotiated the purchase of the property for $15,000 with $4,000 down. It was given the necessary cash to retire the mortgage in 1908. The sale was recorded by the County of Los Angeles on April 12, 1908.

The Forgotten Azusa Street Mission: The Place where the First Pentecostals Met

For years, the building on Azusa Street has also been an enigma. Most people are familiar with the same three or four photographs that have been published and republished through the years. They show a rectangular, boxy, wood frame structure that was 40 feet by 60 feet and desperately in need of repair. Seymour began his meetings in the Mission on April 15, 1906. A work crew set up a pulpit made from a wooden box used for shipping shoes from the manufacturer to stores. The pulpit sat in the center of the room. A piece of cotton cloth covered its top. Osterberg built an altar with donated lumber that ran between two chairs. Space was left open for seekers. Bartleman sketched seating as nothing more than a few long planks set on nail kegs and a ragtag collection of old chairs.

What the new sources have revealed about the Mission, however, is fascinating. The people worshiped on the ground level — a dirt floor, on which straw and sawdust were scattered. The walls were never finished, but the people whitewashed the rough-cut lumber. Near the door hung a mailbox into which tithes and offerings were placed since they did not take offerings at the Mission. A sign greeted visitors with vivid green letters. It read “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin” (Daniel 5:25, kjv), with its Ns written backwards and its Ss upside down. Men hung their hats on exposed overhead rafters where a single row of incandescent lights ran the length of the room.

These sources also reveal that the atmosphere within this crude building — without insulation or air conditioning, and teeming with perspiring bodies — was rank at best. As one writer put it, “It was necessary to stick one’s nose under the benches to get a breath of air.”

Several announced that the meetings were plagued by flies. “Swarms of flies,” wrote one reporter, “attracted by the vitiated atmosphere, buzzed throughout the room, and it was a continual fight for protection.”

A series of maps drawn by the Sanborn Insurance Company give a clear picture of the neighborhood. The 1888 map discloses that Azusa Street was originally Old Second Street. The street was never more than one block in length. It ended at a street paving company with piles of coal, along with heavy equipment. A small house, marked on the map by a “D” for domicile, sat on the front of the property with the address of 87. (See highlighted section.) A marble works business specializing in tombstones stood on the southeast corner of Azusa Street and San Pedro. Orange and grapefruit orchards surrounded the property. On the right of the map a Southern Pacific railroad spur is clearly visible. The City Directory indicates that the neighborhood was predominantly Jewish, though other names were mixed among them.

A second map of the property was published in 1894. Old Second Street had become Azusa Street, and the address had been changed to 312. The house had been moved further back on the property where it served as a parsonage. The dominant building at 312 Azusa Street was the Stevens African Methodist Episcopal Church. At the front of the building a series of tiny parallel lines on the map mark a staircase that stood at the north end of the building providing entry to the second floor, the original sanctuary.

The only known photograph of the church from this period shows three interesting features. First, it shows the original staircase. Second, and less obvious, the original roofline had a steep pitch. Third, three gothic style windows with tracery lines adorned the front wall.

By 1894, the citrus groves had largely disappeared. On the southern side they were replaced by lawn. The smell of orange blossoms and the serenity of the orchard were rapidly being replaced by the banging of railroad cars and the smell of new lumber. A growing number of boarding houses and small businesses, including canneries and laundries, were moving into the immediate area by this time. The property marked “YARD” on the map is the beginning of the lumberyard that soon came to dominate the area. The City Directory reveals fewer Jewish names, and more racial and ethnic diversity in the neighborhood, including African Americans, Germans, Scandinavians, and Japanese.

Stevens AME Church occupied the building at 312 Azusa Street until February 1904 when the congregation dedicated a new brick facility at the corner of 8th and Towne and changed their name to First AME Church. Before the congregation could decide what to do with the property on Azusa Street, however, an arsonist set the vacant church building on fire. The structure was greatly weakened, and the roof was completely destroyed. The congregation decided to turn the building into a tenement house. They subdivided the former second-floor sanctuary into several rooms separated by a long hallway that ran the length of the building. The stairs were removed from the front of the building and a rear stairwell was constructed, leaving the original entry hanging in space. The lower level was used to house horses and to store building supplies, including lumber and nails.

In 1906, a new Sanborn Map was published. (See 1906 map.) The building was marked with the words “Lodgings 2nd, Hall 1st, CHEAP.” The transition of the neighborhood had continued. The marble work still occupied the southeast corner of Azusa Street and San Pedro, but a livery and feed supply store now dominated the northeast corner. A growing lumberyard to the south and east of the property now replaced the once sprawling lawn. A Southern Pacific railroad spur curved through the lumberyard to service this business.

The Apostolic Faith, the newspaper of the Azusa Street Mission between September 1906 and June 1908, later referred to the nearby Russian community. Many of these recent immigrants were employed in the lumberyard. They were not Russian Orthodox Christians as one might guess; they were Molokans — “Milk drinkers.” This group had been influenced by some of the 16th-century Reformers. They did not accept the dairy fasts of the Orthodox Church. They were Trinitarians who strongly believed in the ongoing guidance of the Holy Spirit. Demos Shakarian, grandfather of the founder of Full Gospel Business Men’s International, was among these immigrants who were led to Los Angeles through a prophetic word given in 1855.

Henry McGowan, later an Assemblies of God pastor in Pasadena, was a member of the Holiness Church at the time. He was employed as a teamster. He timed his arrival at the nearby lumberyard so he could visit the Mission during its afternoon services.

This map suggests why some viewed the Mission as being in a slum. A better description would be an area of developing light industry.

In April 1906, when the people who had been meeting at the house at 214 North Bonnie Brae Street were forced to move, they found the building at 312 Azusa Street was for sale. The photograph below taken about the time that the congregation chose to move into the building shows the “For Sale” sign posted high on the east wall of the building, as well as the rear of the tombstone shop. Seymour, pastor of the Azusa Street Mission, and a few trusted friends met with the pastor of First AME Church and negotiated a lease for $8 a month.

An early photograph reveals what the 1906 version of the map indicates. The pitched roof had not been replaced. The building had a flat roof. The staircase that had stood at the front of the building had been removed.

In a sense, this building suited the Azusa Street faithful. They were not accustomed to luxury. They were willing to meet in the stable portion of the building. The upstairs could be used for prayer rooms, church offices, and a home for Pastor Seymour.

Articles of incorporation were filed with the state of California on March 9, 1907, and amended May 19, 1914. The church negotiated the purchase of the property for $15,000 with $4,000 down. It was given the necessary cash to retire the mortgage in 1908. The sale was recorded by the County of Los Angeles on April 12, 1908.

Lucy F. Farrow: The Forgotten Apostle of Azusa

Lucy F. Farrow was born in Portsmouth, VA. Unfortunately, her origins there have not been yet fully traced. Her involvement appeared around the summer of 1905 while working as governess in Parham’s home in Houston.

While in Houston, Farrow met Charles Parham, who came there from Baxter Springs, Kansas, in October 1905 and held meetings in Bryan Hall. Parham was preaching about the earlier outpouring of the Holy Spirit that had occurred in his Bethel Bible College in Topeka, Kansas, in January 1901.

Other sources claim, Lucy F. Farrow received the Holy Ghost a little bit earlier on September 6, 1905 after Parham opened up a month-long meeting in Columbus, Kansas. Along with Parham she witnessed events unfold in Zion, Illinois, where John Alexander Dowie was faltering.

Lucy Farrow was the niece of renowned black abolitionist Frederick Douglass. She was serving as pastor of a holiness church in Houston in 1905 when Charles Parham engaged her to work as a governess in his home. Farrow carried the Pentecostal embers back to Texas, on to her home state Virginia and later to Liberia. Her aptitude for igniting the supernatural gifts among others was evident at a 1906 camp meeting near Houston when some 25 seekers stood lined up in a row in front of her. When Farrow “laid hands upon them…many began to speak in tongues at once.”

Although William J. Seymour is acknowledged as the leader of the Azusa Street Revival, it was a black woman, Lucy Farrow, who provided the initial spark that ignited that revival. About the time when Seymour departed to Los Angeles in January of 1906, Lucy Farrow and J. A. Warren also arrived there independently. Other sources claim, they had been sent by Parham to help Seymour with his meetings.

Seymour began his meetings at the Santa Fe Mission on February 24, 1906 but was quickly shut down by the pastor Julia W. Hutchins on March 4, 1906 after a consultation with the South Californian Holiness Association.

The meetings then moved to 214 Bonnie Brae St., home of Richard and Ruth Asberry. As a result, Edward S. Lee was the first one was baptized in the Spirit and spoke in other tongues in the late afternoon when William J. Seymour and Lucy F. Farrow laid hands on him for healing at his house. At 7:30 p.m., the group went back to Bonnie Brae for the evening meeting and before the night was over, Jennie Evans Moore and several others joined him.

It has been said that no one associated with the prayer meeting led by Seymour had spoken in tongues until Farrow, at Seymour’s request, arrived on the scene and began laying her hands on people and seeing God fill them with the Holy Spirit as in the book of Acts. She also ministered with power across the southern United States and in Liberia in West Africa. She lived out her final years in Los Angeles, where there were reported healings and remarkable answers to prayer through her ministry.

The FORGOTTEN ROOTS OF THE AZUSA STREET REVIVAL

by HAROLD HUNTER, PH.D.

by HAROLD HUNTER, PH.D.

Writing during the glow of the Azusa Street revival, V.P. Simmons claimed to have 42 years of personal exposure to those who spoke in tongues. Published in 1907 by Bridegroom’s Messenger and circulated as a tract, Simmons chronicled the history of Spirit baptism from Irenaeus (2nd century) up to and including a group from New England whom he personally observed manifesting tongues-speech as they continually partook of a spiritual baptism.1 Identified as Gift People or Gift Adventists, they were widely known for their involvement with spectacular charisms.Early Pentecostal periodicals reported that tongues-speech was known among these groups since the latter part of the 19th century. Some groups were said to number in the thousands.

William H. Doughty, who, by 1855, had spoken in tongues while in Maine, was counted among that number. Elder Doughty moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in 1873 and assumed leadership among those exercising the gifts of the Spirit.3 Doughty’s mantle was passed on to Elder R.B. Swan who, reacting to the Azusa Street revival, wrote a letter explaining that the Gift People in Rhode Island had experienced speaking in tongues as early as 1874–75. (See “The Work of the Spirit in Rhode Island.”) B.F. Lawrence followed Swan’s letter describing an independent account of a woman who spoke in tongues in New York, perhaps prior to 1874, a result of her contact with the Gift People.4 (See “A Wonderful Healing Among The Gift People.”)

Stanley H. Frodsham quotes Pastor Swan’s claim to having spoken in tongues in 1875. Swan speaks of great crowds drawn from five states and specifically mentions his wife — along with Amanda Doughty and an invalid hunchback who was instantly healed — among those who spoke in tongues during this time.

Simmons said that Swan’s group adopted the name “The Latter Rain” after the advent of the Pentecostal movement. Their activities extended throughout New England states, especially Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, and Connecticut, with the 1910 Latter Rain Convention held October 14–16 in Quakertown, Connecticut. Frank Bartleman frequently referred to joint speaking engagements with Swan, specifically recounting a 1907 tour that included a convention in Providence, Rhode Island, where he spoke 18 times.

Previously overlooked in related investigations is whether the Doughty family counted among the Gift People overlap with the Doughty who traveled with Frank Sandford. Lawrence attests that Swan’s circle included William H. Doughty’s daughter-in-law, Amanda Doughty, and her unnamed husband, an elder in the Providence congregation.8 Simmons says that William H. Doughty had two sons, the oldest, Frank, who was ordained. Could the unnamed brother of Frank be Edward Doughty, who at the end of the 19th century was part of Sandford’s entourage? So it seems.

Most of the groups named here have similar stories. For example, among the Fire-Baptized Holiness ranks was Daniel Awrey who had spoken in tongues in 1890 in Ohio. His residence was in Beniah, Tennessee, where an outbreak of speaking in tongues was reported in 1899. F.M. Britton wrote about people speaking in tongues in his Fire-Baptized revivals that predated the Azusa Street revival. Also, a revival in Cherokee County, North Carolina, in 1896, that gave the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) many of its early leaders reported an outburst of speaking in tongues among several of the adherents. Given the above accounts, there is some debate as to whether Parham first heard speaking in tongues while at Sandford’s Shiloh in Maine or while he was among Fire-Baptized enthusiasts.

THE FOLLOWING ARE THE CATHOLIC LEADERSHIP OR GROUPS RECORDED TO HAVE SPOKEN IN TONGUES:

• ST. HILDEGARD (1098-1179)

• ANTHONY OF PADUA (1195-1231)

• FRANCISCANS (1200S)

• ANGE CLARENUS (1300)

• VINCENT FERRER (1350-1419)

• STEPHEN, MISSIONARY TO GEORGIA (1400S)

• ST. COLETTE (1447)

• LOUIS BERTRAND (1526-1581)

• THE JANSENISTS (1600)

• JEANNE OF THE CROSS (1450S)

• FRANCIS XAVIER (1506-1552)

SHERRILL’S BOOK ALSO LISTS SOME INDIVIDUALS FROM THE 19TH CENTURY WHO REPORT TONGUES-SPEAKING OCCURRING:

- 1855 V.P. SIMMONS

- ROBERT BOYD (DURING MOODY’S MEETINGS)

- 1875 R.B. SWAN

- 1979 W. JETHRO WALTHALL

- MARIA GERBER

MORE BOOKS to STUDY:

- “THEY SPEAK WITH OTHER TONGUES” BY JOHN L. SHERRILL

- “GLOSSOLALIA: TONGUE SPEAKING IN BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, AND “PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE” BY FRANK E. STAGG

- “SPEAKING IN TONGUES: A GUIDE” BY MILLS

- “SPEAKING WITH TONGUES: HISTORICALLY AND PSYCHOLOGICALLY CONSIDERED” BY GEORGE CUTTEN.