The Bulgarian Underground Church

The modern day Pentecost began in Bulgaria in the 1920s as Ukrainian immigrants Zaplishny and Voronaev preached in the Congregational church of Bourgas where several were baptized with the Holy Spirit. In the late 1920s a conservative Pentecostal group emerged and formed the union called the Church of God. After the 1944 Communist Revolution in Bulgaria it continued its existence as an underground organization and was severely persecuted. In 1986, the Bulgarian Church of God joined the Church of God (Cleveland, TN). A national revival followed the fall of the Berlin Wall in which hundreds of thousands of people have been touched by the power of God. Today, the Bulgarian Pentecostal Movement claims over 100,000 members.

The modern day Pentecost began in Bulgaria in the 1920s as Ukrainian immigrants Zaplishny and Voronaev preached in the Congregational church of Bourgas where several were baptized with the Holy Spirit. In the late 1920s a conservative Pentecostal group emerged and formed the union called the Church of God. After the 1944 Communist Revolution in Bulgaria it continued its existence as an underground organization and was severely persecuted. In 1986, the Bulgarian Church of God joined the Church of God (Cleveland, TN). A national revival followed the fall of the Berlin Wall in which hundreds of thousands of people have been touched by the power of God. Today, the Bulgarian Pentecostal Movement claims over 100,000 members.

However, this was hardly the case through the years of persecution when the Bulgarian Church of God refused to register with the Communist state and remained underground for over 45 years. Recently published archives from that era show that the Bulgarian underground church grew slowly during the Communist regime experiencing virtually constant crises in leadership and structure. At the same time the government aggressively attempted to penetrate and influence the organization of the church in order to revert its growth.

One of the earliest archive documents from that era is a 1974 study which reported that the Bulgarian Church of God had 600 members nationwide. By 1981, the membership had grown to over 2,000 members with congregations in 25 cities. The congregation in the capital Sofia had 100-150 members, but grew to over 200 by the end of 1982. At the same time, the Bulgarian Pentecostal Union (registered with the government and affiliated with the Assemblies of God) had approximately 10,000 members.

A detailed list of churches and members was kept in government archives as the secret service was ordered to watch the underground church closely. The agent’s logs from that time show approximately 1,000 known members. This number is only a fraction of the actual membership, which at large remained underground and hidden from the eyes of the agents.

The pressure from the secret service was not able to stop the growth of the underground church. By 1985, the Bulgarian Church of God had grown to 3,000 members nationwide while doubling the number of congregations to over 50. Two years later this number was 4,000 and continued to grow as the central church in the capital Sofia had 600 members and several churches (like the ones in Rouse and Gabrovo) had congregations over 200. In 1989, the Communist regime collapsed and Bulgaria began its journey on the road of democracy. In 1990, the Bulgarian Church of God received government recognition as an official denomination representing over 5,000 nationwide to become the fastest growing Bulgarian church with over 30,000 members today.

Newsweek: Bulgarian Ski Resorts Trendiest in Eastern Europe

Bulgaria boasts Eastern Europe’s most fashionable resorts, says an article in the January 14 Newsweek magazine issue. The magazine points out the opportunities to spend a holiday at Bulgaria’s top ski resorts like Borovetz and Pamporovo at low prices, which are a fourth of what tourists would pay in France’s or Switzerland’s winter resorts. “There has been a massive increase in the popularity in skiing in Eastern Europe,” says Chris Rand of the Britain-based tour company Balkan Holidays. EUR 150 million have been invested in Borovetz to make it a “modern European resort” with an additional 80 kilometers of family-friendly runs, Newsweek says.

Bulgaria boasts Eastern Europe’s most fashionable resorts, says an article in the January 14 Newsweek magazine issue. The magazine points out the opportunities to spend a holiday at Bulgaria’s top ski resorts like Borovetz and Pamporovo at low prices, which are a fourth of what tourists would pay in France’s or Switzerland’s winter resorts. “There has been a massive increase in the popularity in skiing in Eastern Europe,” says Chris Rand of the Britain-based tour company Balkan Holidays. EUR 150 million have been invested in Borovetz to make it a “modern European resort” with an additional 80 kilometers of family-friendly runs, Newsweek says.

NATO Top Commander Eyes Bulgarian Contenders US Bases

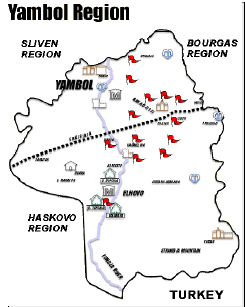

US Airbase to be Built in the Village of Bezmer in the Yambol Region

US Airbase to be Built in the Village of Bezmer in the Yambol Region

NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and commander of American troops in Europe, General James Jones, arrived in Bulgaria for a two-day visit to Bulgaria. at the invitation of the Chief of Army Staff, Gen Nikola Kolev. The future stationing of US bases in the Balkan country toped the agenda of General Jones, who visit ed eligible units and sites on the territory of the country, including the firing field at Novo Selo and the air base at Bezmer in the Yambol region.

Bulgaria, Romania and Poland are favorite destinations for hosting US bases. At the end of 2003 Bulgaria’s Parliament expressed support for the future stationing of US bases in the Balkan country. The Black Sea port of Bulgaria, which became a full-fledged NATO member in April last year, has already been used by the US army during the Iraq war.

General Jones last visited Bulgaria a year ago when he highly assessed the reforms in Bulgaria’s army as well as the work of the Balkan country’s military forces participating in NATO peacekeeping missions.

Decommunization.org

![]() Each year Cup & Cross Ministries invests in one significant media project. This tradition was started in 1996 to provide a ministry outreach with comprehensive media coverage. The 2005 project is a website dedicated to the subject of decommunization – a global effort to present archive documentation revealing the destructive effect of communist regimes. For more information, visit the project’s website: www.decommunization.org.

Each year Cup & Cross Ministries invests in one significant media project. This tradition was started in 1996 to provide a ministry outreach with comprehensive media coverage. The 2005 project is a website dedicated to the subject of decommunization – a global effort to present archive documentation revealing the destructive effect of communist regimes. For more information, visit the project’s website: www.decommunization.org.

The Year of the Spirit

We live in the 21st century. What was just a dream several years ago is a global reality today.

We live in the 21st century. What was just a dream several years ago is a global reality today.

Unfortunately, as the world wanders in the crossroads of postmodernity, between alternative ideologies and lifestyles, churches are being closed every day. This fact alone signifies that in our search for personal spirituality and excellence for ministry in 2005, we cannot trust world governments, political powers or economical conglomerates. The only One who remains faithful to the Church today is the Spirit of God, and more than ever before in the beginning of the 21st century we must again pray with the cry, “Holy Ghost we need thee …”

This is exactly what we are planning to do as we dedicating 2005 as the Year of the Spirit. We are committed to take only the steps which God directs and we want to participate in the work of other ministries and churches which are willing to do the same. If you are planning a revival, mission campaign, youth rally or other special services we are available. Please feel free to contact us.

Are you Mission Ready?

Evaluation is the act of finding out if a person or groups has accomplished what it set out to do. Sincere evaluation of the local church missions program is a problem. We avoid such evaluation by assuming people automatically incorporate new learning in their lives and by assuming that programs cannot be improved very much even if they were evaluated. Too often they are labeled as good or bad by one person or by those who manage or plan the program. Both learners and administrators must cooperate in organized evaluation. [more]

Evaluation is the act of finding out if a person or groups has accomplished what it set out to do. Sincere evaluation of the local church missions program is a problem. We avoid such evaluation by assuming people automatically incorporate new learning in their lives and by assuming that programs cannot be improved very much even if they were evaluated. Too often they are labeled as good or bad by one person or by those who manage or plan the program. Both learners and administrators must cooperate in organized evaluation. [more]

Revival BULGARIA

Bulgarian Church of God

Since the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 the Pentecostal churches in Bulgaria have been instrumental in the proceeds of reaching the minorities in Bulgaria. Over 10,000 Muslims have accepted Christ. The rapid growth of the Bulgarian Church of God has influenced large portion of the ethnic minorities in the country. As a result large minority congregations have emerged (for example Samokov with membership of 1,700, and Razlog of 450). In 2002 the ratio of ethnic groups within the Bulgarian Church of God was:

Since the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 the Pentecostal churches in Bulgaria have been instrumental in the proceeds of reaching the minorities in Bulgaria. Over 10,000 Muslims have accepted Christ. The rapid growth of the Bulgarian Church of God has influenced large portion of the ethnic minorities in the country. As a result large minority congregations have emerged (for example Samokov with membership of 1,700, and Razlog of 450). In 2002 the ratio of ethnic groups within the Bulgarian Church of God was:

Bulgarians: 66% Gypsies: 20.3%

Turkish: 6.5 % Russian: 3.7 %

Armenians: 2.5 % Others: 1%

The Bulgarian Church of God strives to supply not only for the spiritual needs in the minority communities where they minister, but also respond to the drastic need for food and heat. The Bulgarian Church of God has planned in the year 2002 to increase our Gipsy membership by 80% and thus to develop Pentecostal influence over more than 75% of the Gipsy community in Bulgaria.

2004 Annual Ministry Report

Click on the picture do view full report (PDF)

Тhe following is the 2004 annual report of the work of our ministry in Bulgaria. We thank you for your prayers as our work in Bulgaria keeps growing.

Statistics 2004:

Churches: 13 (plus 6 project churches)

Team: 10 (plus 6 in training)

Monthly Average Traveling: 781 miles

Monthly Average Services: 76 (over 95 services per month during the warm periods. The number of services about are 50 during the winter season due to traveling difficulties).

Ethnic Minorities in Bulgaria

The country of Bulgaria was established in 681 A.D. on the Balkan Peninsula. Through the centuries of its existence, ethnic and religious groups have crossed its territory, reforming its borders and creating a multicultural context where more than 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Today the Bulgarian people live along with several ethnic minorities in the clash between Christianity, Muslim and Judaism.

The country of Bulgaria was established in 681 A.D. on the Balkan Peninsula. Through the centuries of its existence, ethnic and religious groups have crossed its territory, reforming its borders and creating a multicultural context where more than 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Today the Bulgarian people live along with several ethnic minorities in the clash between Christianity, Muslim and Judaism.

Bulgaria could be referred to as a country of emigration, since there were several major migration waves mostly toward Turkey during the 20th century. Nevertheless, the population’s ethnic composition remains relatively homogeneous, 85.7% being Bulgarians, yet characterized by ethnic and religious diversity among the rest of its population. The two major ethnic groups are Turks and Gypsies, which represent 9.4% and 3.7% of the Bulgarian nation. The number of Jews has decreased tangibly both in absolute and relative figures due to a massive emigration of about 45,000 people to Israel in 1848. It is worth mentioning that Bulgaria is one of the few European countries which preserved its Jewish community during the World War II. Not a single Jew from Bulgaria was deported to Nazi concentration camps.

As regards religion and language, Orthodox Christianity and Bulgarian are the most widespread ones. The huge majority of Bulgarians (and around 60% of Gypsies plus 1% of ethnic Turks), declares adherence to the Christian cultural tradition. The second significant religion is Islam, professed by most Turks, all Bulgarian Muslims, and 39% of the Gipsy/Roma population. All Bulgarians speak their mother tongue. Almost the same is true for the Turks who speak Bulgarian as a second language beside Turkish (one third of their families even speak Bulgarian at home).

The Turks are the largest minority group and at the same time the one with the highest degree of ethnic consciousness. They are basically concentrated in two regions – in northeastern Bulgaria and in the Rhodopes region at the Turkish frontier. The Turkish population is mostly rural: 68 out of 100 people live in villages and 32 in cities.

The Turkish Minority

The Turkish community in Bulgaria is conditioned by two opposite factors: a birth-rate higher than the national average and numerous, massive emigration waves. The first emigration of Turkish people occurred after Liberation from the Turkish yoke. In the 1878-1912 period, Bulgaria saw the exodus of 350,000 Muslims (Turks, Bulgarian Muslims, Circassians, and Tartars). Roughly 100,000 of them had emigrated by 1884, 250,000 after unification of Eastern Romenlia and the Bulgarian Principality from 1885 till World War I. Until 1934, the average annual number of emigrants was 10,000, and after the nationalistic coup d’etat in 1934 it became 20,000. The next massive wave of emigration occurred at the beginning of the 1950’s: 155,000 persons. Another 115,000 left the country after the signing of the Bulgarian-Turkish Agreement on reuniting separated families in 1968. The emigration peak was in 1989-1992 when more than 300,000 left the country.

The Roma Community

The third largest ethnic and cultural group in the country is the Gypsies (or Roma). According to the last census, their number is 313,396. Analysts insist that these figures should be handled carefully because, as they say, 30% of the Gypsies prefer to declare external ethnic self-identification. Their larger part is from the Muslim Gypsy circles that present themselves as Turks; a part of the Christian Gypsies identify themselves as Bulgarians, and a third small part – as Wallachs (Romanian origin). The variety of empirical references of self-identification is manifested in regard to both the ethnic adherence and denomination, and to the language. Most Gypsies speak more than one language at home, the most used being the Gypsy language (67%), followed by Bulgarian (51%), and Turkish (34%). The situation of the Roma population in the country is extremely complicated. Their living conditions are more than poor. Despite the fact the at the end of 1970’s about 15,000 Roma families obtained long-term, low-interest loans to construct homes, a lot of them are still living in poor quarters resembling ghettos. The Roma child mortality rate is much higher than that of the Bulgarians: 240 per 1,000 versus 40 per 1,000, and some diseases like tuberculosis is three times more frequent. The degree of unemployment is three times higher than the national average. The Roma community is characterized by a lower level of education, which makes its representatives less competitive. There are strong prejudices against the Gypsies shared by the Bulgarian majority and other major minority groups. Unfortunately, the media and especially some nationalistic-oriented newspapers play a considerable role in reproducing and expanding these negative attitudes by emphasizing that Gypsies have a higher crime rate than other groups.

Some Special Cases (Pomacs and Macedonians)

Both groups represent special cases in terms of history, magnitude, and impact on political life. More significant are the Bulgarian Muslims (‘Pomaks’) because of their number and ‘borderline’ position between the Bulgarian majority, with which they share a common mother tongue, and the Turkish minority whose religion they profess. Bulgarian Muslims are ethnic Bulgarians who were converted to Islam during the Ottoman yoke. Their number was approximately 20,000 immediately after restoration of the Bulgarian state in 1878, and by the 1920’s reached 88,000. The sharp increase in figures between 1910 and 1920 was due to re-integration of Bulgaria with newly liberated territories in the Rhodopes and Rila regions. Present day their number is estimated between 200,000 and 280,000. In spite of their ethnic origin, Bulgarian Muslims’ historical fate is identical in many respects to that of other Muslim groups. Bulgarian Muslims have been subject to influences for assimilation in both possible regards. On one hand, study of Turkish language has been stimulated in order to integrate all Muslims into Bulgarian society as a whole. The result is that the Turkish language is perceived as a mother tongue by some 6% of community members.

The issues of ‘Macedonians’ are not any less complicated or controversial. One thesis defines them as a regional community based on the argument that they are an Orthodox population speaking a Bulgarian dialect in common with Bulgarian history, traditions, and values. Based on the right to self-determination, a contrary thesis defines them as a separate ethno-cultural community. Both views have political expression in the activities of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization -VMRO (a party seated in Parliament), and the United Macedonian Organization – OMO Ilinden (an unrecognized and unregistered separatist movement). Bulgarian policy towards ‘Macedonians’ has swayed between two extremes. In the 1940’s, much support was given to the idea of a socialist-oriented Balkan Federation (to includes all Balkan states and thus to resolve every and each ethnic and religious problem in the area). The population of the Pirin district bordering FRY Macedonia and Greece was stimulated, even forcibly, to identify itself as ‘Macedonians’. According to the 1956 census, 187,789 Bulgarians declared themselves as ‘Macedonians’. Later on, the policy altered sharply, and ‘Macedonians’ disappeared from official statistics. They have not turned up there till today.