Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith

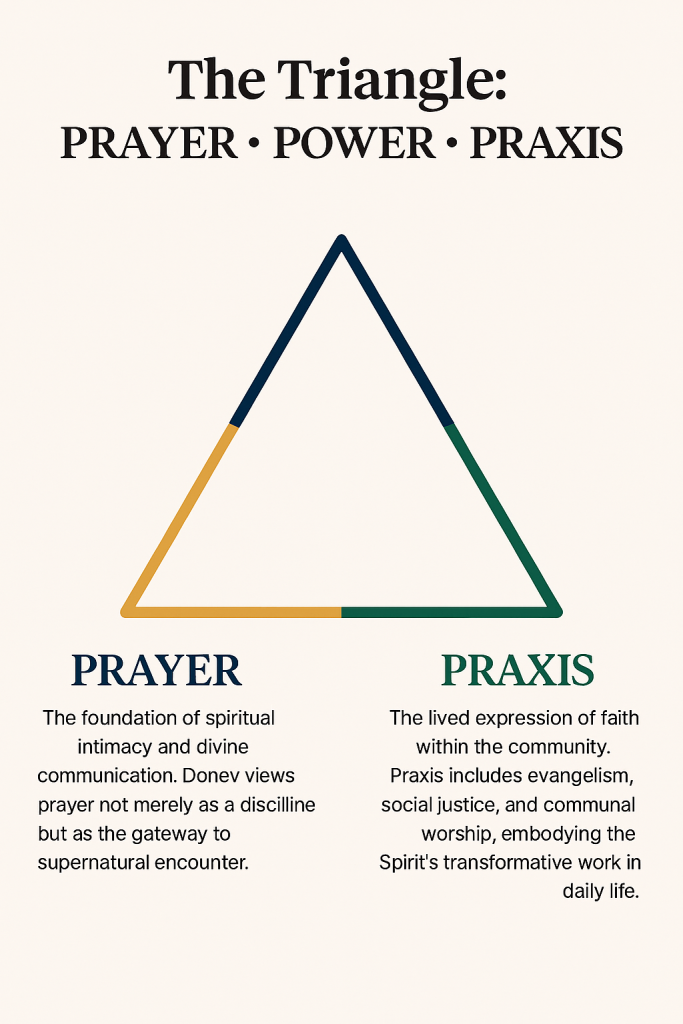

This is one of Donev’s most recognized frameworks. It emphasizes three core elements of Pentecostal spirituality:

- Prayer: Seen as the starting point of spiritual communication and personal experience with God.

- Power: The manifestation of divine presence through spiritual gifts and supernatural experiences.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community, reflecting both personal and collective identity.

This triangle encapsulates the holistic nature of Pentecostalism, where theology is deeply rooted in experience rather than abstract doctrine.

Restorationist Theology

Donev builds on the idea of primitivism—a return to the faith and practices of the early church. He critiques Wesleyan frameworks like the quadrilateral (Scripture, tradition, reason, experience) as insufficient for Pentecostal identity, arguing that Pentecostalism goes beyond Wesley to reclaim the apostolic era.

Historical-Theological Contributions

In his book The Unforgotten, Donev explores the theological roots of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria, tracing its development through key figures like Ivan Voronaev and the influence of Azusa Street missionaries. His research highlights:

- Trinitarian theology among early Bulgarian Pentecostals, shaped by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology and Western Pentecostal doctrine.

- Free will theology, emphasizing Armenian views over Calvinist predestination, due to Bulgaria’s Orthodox heritage and missionary influences.

Other Notable Works

- The Life and Ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev: A historical-theological study of one of the pioneers of Slavic Pentecostalism.

- Doctrine of the Trinity among Early Bulgarian Pentecostals: Explores how the Trinity was experienced and understood in early Eastern European Pentecostal context

The Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith: A Framework of Experience and Restoration

Introduction

Pentecostal theology has long emphasized the experiential dimension of faith—where divine encounter, spiritual gifts, and communal expression converge. Among the contemporary voices shaping this discourse, Dony K. Donev offers a compelling framework known as the Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith, which seeks to restore the apostolic essence of early Christianity. This essay explores the theological contours of Donev’s model and compares it with other influential Pentecostal and charismatic paradigms.

The Triangle: Prayer, Power, Praxis

At the heart of Donev’s framework lies a triadic structure:

- Prayer: The foundation of spiritual intimacy and divine communication. Donev views prayer not merely as a discipline but as the gateway to supernatural encounter.

- Power: Manifested through the gifts of the Spirit—healing, prophecy, tongues, and miracles. This element reflects the Pentecostal emphasis on dunamis, the Greek term for divine power.

- Praxis: The lived expression of faith within the community. Praxis includes evangelism, social justice, and communal worship, embodying the Spirit’s transformative work in daily life.

This triangle is not hierarchical but interdependent. Prayer leads to power, power fuels praxis, and praxis deepens prayer. Donev’s model thus reflects a restorationist impulse, aiming to recover the vibrancy of the early church as seen in Acts.

Comparison with Wesleyan Quadrilateral

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral—Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience—has historically shaped Methodist and Holiness theology. Pentecostals have often adopted this model, emphasizing experience as a key source of theological reflection.

However, Donev critiques this framework as insufficient for Pentecostal identity. He argues that Pentecostalism is not merely an extension of Wesleyanism but a distinct restoration movement. While Wesley’s model is epistemological, Donev’s triangle is ontological and missional, rooted in being and doing rather than knowing.

Comparison with Classical Pentecostal Theology

Classical Pentecostalism, as shaped by early 20th-century leaders like Charles Parham and William Seymour, emphasized:

- Initial evidence doctrine: Speaking in tongues as proof of Spirit baptism.

- Dispensational eschatology: A belief in imminent rapture and end-times urgency.

- Holiness ethics: A call to moral purity and separation from the world.

Donev’s framework diverges by focusing less on doctrinal distinctives and more on spiritual vitality and historical continuity. His emphasis on praxis aligns with newer Pentecostal movements that prioritize social engagement and global mission.

Comparison with Charismatic Theology

Charismatic theology, especially within mainline and evangelical churches, often emphasizes:

- Renewal within existing traditions

- Broad acceptance of spiritual gifts

- Less emphasis on tongues as initial evidence

Donev’s triangle shares the Charismatic focus on spiritual gifts but retains a Pentecostal distinctiveness through its restorationist lens. He seeks not just renewal but recovery of primitive faith, making his model more radical in its ecclesiological implications.

Eastern European Context and Trinitarian Theology

Donev’s work is also shaped by his Bulgarian heritage. He highlights how early Bulgarian Pentecostals embraced a Trinitarian theology informed by Eastern Orthodox pneumatology. This contrasts with Western Pentecostalism’s often fragmented view of the Spirit.

His emphasis on free will theology—influenced by Arminianism and Orthodox thought—also sets his framework apart from Calvinist-leaning Charismatic circles.

Conclusion

Dony K. Donev’s Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith offers a rich, experiential, and historically grounded model for understanding Pentecostal spirituality. By centering prayer, power, and praxis, Donev reclaims the apostolic fervor of the early church while challenging existing theological paradigms. His framework stands as a bridge between classical Pentecostalism, Charismatic renewal, and Eastern Christian traditions—inviting believers into a deeper, more dynamic walk with the Spirit.

Comparative Insights from Leading Pentecostal Scholars

Gordon Fee: Scripture-Centered Pneumatology

Fee’s scholarship emphasizes the Spirit’s role in New Testament theology, particularly in Pauline writings. While he critiques traditional Pentecostal doctrines like initial evidence, he affirms the Spirit’s transformative presence. Compared to Donev, Fee’s approach is exegetical and text-driven, whereas Donev’s triangle is experiential and restorationist, prioritizing lived encounter over doctrinal precision.

Stanley M. Horton: Doctrinal Clarity and Holiness

Horton’s work, especially in Bible Doctrines, provides a systematic articulation of Pentecostal beliefs, including Spirit baptism and sanctification. His theology is deeply rooted in Assemblies of God tradition. Donev diverges by de-emphasizing denominational boundaries, focusing instead on the primitive church’s egalitarian and Spirit-led ethos.

Craig Keener: Charismatic Experience and Historical Context

Keener bridges academic rigor with charismatic openness, especially in his work on miracles and Acts. His emphasis on historical plausibility and global charismatic phenomena aligns with Donev’s praxis-driven model. However, Keener’s scholarship is more apologetic and evidential, while Donev’s triangle is formational and communal.

Frank Macchia: Spirit Baptism and Trinitarian Theology

Macchia’s theology centers on Spirit baptism as a metaphor for inclusion and transformation, often framed within Trinitarian and sacramental lenses. Donev shares Macchia’s Trinitarian depth, especially in Eastern European contexts, but leans more toward neo-primitivism and ecclesial simplicity.

Vinson Synan: Historical Continuity and Global Pentecostalism

Synan’s historical work traces Pentecostalism’s roots and global expansion. Donev builds on this by reclaiming Eastern European Pentecostal narratives, such as those of Ivan Voronaev. Both emphasize restoration, but Donev’s triangle is more prescriptive, offering a model for future church practice.

Robert Menzies: Missional and Contextual Theology

Menzies focuses on Pentecostal mission and theology in Asian contexts, often challenging Western assumptions. His emphasis on Spirit empowerment for mission resonates with Donev’s praxis element. Yet, Donev’s model is more liturgical and communal, drawing from Orthodox and Puritan influences.

Cecil M. “Mel” Robeck: Ecumenism and Pentecostal Identity

Robeck’s work on Pentecostal ecumenism and global dialogue complements Donev’s inclusive vision. Both advocate for Pentecostal distinctiveness without isolation, though Donev’s triangle is more grassroots and revivalist, aimed at local church transformation.

Implications for Church Practice

Donev’s triangle offers a practical blueprint for churches seeking renewal:

- Prayer ministries that foster intimacy and prophetic intercession.

- Power encounters through healing services and spiritual gift activation.

- Praxis initiatives like community outreach, justice advocacy, and discipleship.

Compared to other scholars, Donev’s model is less academic and more actionable, designed to reignite the apostolic fire in everyday church life.

Pentecostal Triangle of Primitive Faith

The modern call for Primitivism derives from the idea of personal experience with God. There is yet no truth for and about Pentecostalism that does not emerge from experience. Irrational in thinking and in an intimate parallel to the story of the Primitive Church, Pentecostalism combines the discomfort and weakness of the oppressed and persecuted. It is the story of one and yet many that excels through the piety of the search for holiness and the power of the supernatural experience of Pentecost. It is the call for the reclaiming and restoration of “the faith once delivered to the saints.”

Such an idea of “looking back to the church of antiquity” derives from a Puritan background and is indisputably Wesleyan. In a letter to the Vicar of Shoreham in Kent, Wesley writes that the parallel between the present reality and the past tradition must remain close. For Wesley, the primitive church was the church of the first three centuries. Equality in the community as in the primitive church was the context in which Wesley ministered. Everyone was allowed to preach, both deacons and evangelists, and even women “when under extraordinary inspiration”

Of course, for Wesley, the Primitive Church was restored with the Church of England. The Pentecostal response was quite different, “The Methodists say that John Wesley set the standard. We go beyond Wesley; we go back to Christ and the apostles, to the days of pure primitive Christianity, to the inspired Word of truth.” The main characteristic of restoration was the personal experience of God. This experience was vividly presented by the Wesleyan interpreters in the quadrilateral along with reason, tradition and scripture. Such a scheme, however, may not be fully sufficient to describe the Pentecostal identity, as well as the paradigm of the Primitive Church.

The experience of God in a Pentecostal context carries a more holistic role, which is connected with the expression of the individual’s story and identity in both personal and corporate ecclesial settings. Through the experience then, they become a collaboration of the story of the many, and at the same time remain in the boundaries of their personal identity. The experience of both the individual and the community that holistically and circularly surrounds Pentecostalism is expressed in prayer, power and praxis.

Since Pentecostalism is based on the personal experience of God, prayer as the means of spiritual communication is its beginning. Being the source of spiritual power in the individual’s life it becomes the means of existence within the community of believers. Power derives only from God through a spiritual relationship which expressed through prayer, develops as a factor of constant change. The product is a unique praxis, which in the quest for church holiness and personal morality appeals for redefinition of the original ecclesial purpose and identification with the lives of the first Christians. The triangular formula of prayer, power and praxis is then the basis for Pentecostal theology.

Pentecostals claim primitivism aplenty, conformity to the apostolic experience of Pentecost and the Book of Acts. It affirms that modern Christianity can rediscover and re-appropriate the power of the Holy Spirit, described in the New Testament and particularly in Acts of the Apostles. In a social context, it was a call against public injustice. Globally the Pentecostal movement was a powerful revival that appeared almost simultaneously in various parts of the world in the beginning of the twentieth century. In the United States it occurred during the time of spiritual search.

During the first seventy years of national life of the USA barely 1.6 million immigrants arrived. In 1861-1900 fourteen million entered the country, and it was precisely within the recorded decade of 1901-10, with 8.8 million immigrants, that the Pentecostal movement began. The mass migration was in an immediate connection with the rapid urbanization and industrialization occurring in a chronological parallel. Since first generation immigrants are usually rootless, combined with sociological changes, the context created a search for identity and roots. In America, Pentecostalism came as an answer to this search.

In parallel, the beginning of the Church of God was a call for restoration and a literal return to the Primitive Church. It was The Christian Union committed to “restore primitive Christianity.” In its early years the Church of God focused on four main characteristics of the Church from Acts: (1) great outpouring of the Spirit, (2) great “ingathering of souls,” (3) tongues of fire and (4) spread of the Gospel. Similar to the Early Church, it began in the context of persecution, presence and parousia. While heavily persecuted the Church of God constantly remains in the presence and guidance of the Holy Spirit in a firm expectancy of the return of Christ. The Genesis of the Church of God was a restoration of the Pentecostal prayer, power and praxis of the Primitive Church.

Pentecostal Framework of Primitive Faith: Comparative Insights from Leading Pentecostal Scholars

Gordon Fee: Scripture-Centered Pneumatology

Fee’s scholarship emphasizes the Spirit’s role in New Testament theology, particularly in Pauline writings. While he critiques traditional Pentecostal doctrines like initial evidence, he affirms the Spirit’s transformative presence. Compared to Donev, Fee’s approach is exegetical and text-driven, whereas Donev’s triangle is experiential and restorationist, prioritizing lived encounter over doctrinal precision.

Stanley M. Horton: Doctrinal Clarity and Holiness

Horton’s work, especially in Bible Doctrines, provides a systematic articulation of Pentecostal beliefs, including Spirit baptism and sanctification. His theology is deeply rooted in Assemblies of God tradition. Donev de-emphasizes denominational boundaries, focusing instead on the primitive church’s egalitarian and Spirit-led ethos.

Craig Keener: Charismatic Experience and Historical Context

Keener bridges academic rigor with charismatic openness, especially in his work on miracles and Acts. His emphasis on historical plausibility and global charismatic phenomena aligns with Donev’s praxis-driven model. However, Keener’s scholarship is more apologetic and evidential, while Donev’s triangle is formational and communal.

Frank Macchia: Spirit Baptism and Trinitarian Theology

Macchia’s theology centers on Spirit baptism as a metaphor for inclusion and transformation, often framed within Trinitarian and sacramental lenses. Donev shares Macchia’s Trinitarian depth, especially in Eastern European contexts, but leans more toward neo-primitivism and ecclesial simplicity.

Vinson Synan: Historical Continuity and Global Pentecostalism

Synan’s historical work traces Pentecostalism’s roots and global expansion. Donev builds on this by reclaiming Pentecostal narratives, such as those of Ivan Voronaev. Both emphasize restoration, but Donev’s triangle is more prescriptive, offering a model for future church practice.

Robert Menzies: Missional and Contextual Theology

Menzies focuses on Pentecostal mission and theology in Asian contexts, often challenging Western assumptions. His emphasis on Spirit empowerment for mission resonates with Donev’s praxis element. Yet, Donev’s model is more legitimately communal, drawing from Orthodox and Puritan influences.

Cecil M. “Mel” Robeck: Ecumenism and Pentecostal Identity

Robeck’s work on Pentecostal ecumenism and global dialogue complements Donev’s inclusive vision. Both advocate for Pentecostal distinctiveness without isolation, though Donev’s triangle is more grassroots and revivalist, aimed at local church transformation.

Implications for Church Practice

Donev’s triangle offers a practical blueprint for churches seeking renewal:

- Prayer ministries that foster intimacy and prophetic intercession.

- Power encounters through healing services and spiritual gift activation.

- Praxis initiatives like community outreach, justice advocacy, and discipleship.

Compared to other scholars, Donev’s model is less academic and more actionable, designed to reignite the apostolic fire in everyday church life.