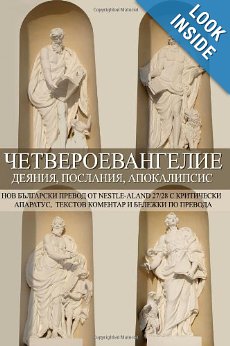

The Four Gospels of the New Bulgarian Translation Published

August 15, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication, Research

We are both happy and humbled to announce the publication of the Tetraevangelion of of the New Bulgarian Translation including:

- Matthew (2011)

- Mark (2010)

- Luke: Gospel and Acts (2013)

- John: Gospel, Epistles and Apocalypse (2007)

This final volume has been almost ten years in the making as it combines all four previously published volumes. It is new literal translation in the Bulgarian vernacular directly from the Nestle Aland Novum Testamentum (27/28 editions).

We thank friends and foes for the internal motivation without which this work would have never been completed.

We are currently working on another similar project, namely the publication of a Study New Testament in Bulgarian, which will be ready for print by the end of this summer.

Pentecostal Bible Schools In the United States

- ACTS International Bible College in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. Member of ACEA.

- Advanced Institute of Ministry in San Francisco. AIM is a member of ACEA.

- Advantage College in Sacramento, CA. International Pentecostal Holiness Church

- Advocate Institute of Advocate Ministries in Birmingham, Alabama area. Member of ACEA.

- All Nations Traning Center of Metro Christian Fellowship in Kansas City. ANTC offers the Transit School of Leadership, and the CPx church planting experience course.

- All Saints Bible College Sponsored by the International Church of God in Christ (COGIC), with headquarters in Memphis, TN.

- Alpha Bible College & Seminary “accredited Bible college through our affiliation with School of Bible Theology, San Jacinto, CA”.

- American Indian College Assemblies of God.

- Assemblies of God Theological Seminary

- Beulah Heights Bible College founded in 1918, the Southeast’s oldest Bible College. In Atlanta, Georgia.

- Bethany College of Scotts Valley, CA. Assemblies of God

- Bethesda Christian University Connecting Korea and America: a Pentecostal/charismatic Christian university for

Korean speaking students. Main campus in Anaheim, California (USA) and two extension campuses in Seoul, S. Korea.

Korean speaking students. Main campus in Anaheim, California (USA) and two extension campuses in Seoul, S. Korea. - Black Hills Indian Bible College Assemblies of God.

- Brewer Christian College and Graduate School in Jacksonville, Florida.

- Brownsville Minisitry Training Center The Elisha Project: “offering a two-year program emphasizing hands-on, practical ministry and leadership training through fathering and mentoring from leaders passionate about discipleship.”

- Calvary Chapel Bible College in Murrieta, California. See also their Extension Campuses in the United States and around the world.

- Calvary Chapel Menifee School of Ministry in Menifee, California.

- Calvary Chapel Murrieta School of Ministry in Murrieta, California.

- Cathedral Bible College of Myrtle Beach, SC.

- Central Bible College in Springfield, Missouri. Assemblies of God.

- Central Theological College (Formerly Spectrum Bible College) offering two-year Bible program and a one-year ministry practicum.

- Charles H. Mason Seminary Part of the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta.

- Chico Extension of the Calvary Chapel Bible College in Chico, California.

- Christ for the Nations Institute in Dallas, TX.

- Christian Life College educating Pentecostal/charismatics for over 50 years in Chicago.

- Christian Life College in Stockton, California.

- Church of God Educational Institutions Links to ministry training centers affiliated with Church of God (Cleveland, TN) including Lee University; Pentecostal Theological Seminary(Formerly the Church of God Theological Seminary); Hispanic Institute of Ministry (El Instituto Ministerial Hispano) in Dallas, Texas;

Han Young Theological University (formerly Korean Theological College) in Seoul, Korea; European Bible Seminary; Colegio Biblico Pentecostal (Puerto Rico Bible College); and others.

Han Young Theological University (formerly Korean Theological College) in Seoul, Korea; European Bible Seminary; Colegio Biblico Pentecostal (Puerto Rico Bible College); and others. - Coastland University affiliated with the Calvary Chapel fellowship of churches.

- Columbia Evangelical Seminary distance mentorship program and classroom setting in Buckley, WA.

- Cornerstone Bible Institute and Seminary in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Part of the apostolic and cell-based church movement Cornerstone Church and Ministries International and member of ACEA.

- Cornerstone School of Ministry operated by Cornerstone Chapel in Medina, Ohio.

- Cottonwood School of Ministry Part of the Cottonwood Christian Center in Los Alamitos, California.

- Covenant Bible College & Seminary (overseen by the Pentecostal Holiness Church of America).

- DOMATA School of Missions. Classes held at the Mark Brazee Ministries office complex in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma.

- East Texas Theological Seminary

- Elim Bible Institute in Lima, NY.

- Emmanuel Bible Institute of Ministry operated by Emmanuel Christian Center (Foursquare) in Salina, Kansas.

- Emmanuel College affiliated with International Pentecostal Holiness Church.

- Escondido Bible College Located in North San Diego County, California. Formerly Cathedral Bible College. Affiliated with the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

- Eugene Bible College in Eugene, Oregon. Affliated with the Open Bible Churches headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa.

- Evangel University in Springfield, MO. Assemblies of God.

- Faith Christian Fellowship School Of Ministry

- Faith Chrisitan University with Main Campus in Orlando, Florida, extension campuses and internet distance learning.

- Faith School of Theology A ministry school in Charleston, Maine founded in 1959. A Berean Study Center (Assemblies of God curriculum).

- FIRE School of Ministry

- Florida Christian University Study in a classroom or in the distance learning program.

- For a complete list of Foursquare Bible Institutes, Colleges, and Schools of Ministry see their National Christian Education index. Numerous local churches offer institutes and certified ministry training including: Emmanuel Bible Institute of Ministry operated by Emmanuel Christian Center in Salina, KS; Angelus Bible Institute in Los Angelus, California; Institute of the Bible and Ministry operated by Living Way Fellowship in Littleton, Colorado; Hispanic Theological Institute of the Northwest in Wenatchee, Washington; Facultad de Teologia in Montebello, CA; New Life Foursquare Leadership Training Institute in Canby, Oregon; V.I.D.A. Instituto Biblico (A.B.I. Extension) in Chino, California; Yellowstone Valley Bible Instituteoperated by Faith Chapel in Billings, Montana; Praise School of Ministry in Los Angeles, California; Victory School of Ministry in Ada, Oklahoma; Logos in Moreno Valley, California; and many more. See the list for current contact information when website is not available.

- Free Gospel Bible Institute Over 45 years educating and preparing men and women for Pentecostal ministry, in Export, Pennsylvania.

- Full Gospel Baptist Bible Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Golden Springs Calvary Chapel Bible College extension campus at Calvary Chapel Golden Springs in Diamond Bar, California.

- Grace Bible College and Seminary in Roanoke, Alabama. Founded in 2003 by Bishop Lyndon B. Hutcherson. Offering distance and classroom instruction.

- Grace Bible School located on the campus of Word of Grace Church (pastored by Gary Kinnaman) in Mesa, Arizona.

- Grace Christian University A theological training program that offers affordable and accredited higher Christian education to build faith and develop culturally rooted Christians leaders around the world. On campus, correspondence, and extension campus programs available.

- Grand Canyon University in Phoenix, AZ. Also offering online degrees in Chinese.

- Greater Grace Bible College in Tacoma, Washington. Extension school of Maryland Bible College & Seminary.

- Healing River International School of Ministry Member of ACEA.

- Hebron Life Bible College & Seminary In Blanchard, OK. Founded by John & Sharon Rathbun.

- Heritage Bible College in Dunn, North Carolina. Affiliated with Pentecostal Free Will Baptist Church

- Holmes Bible College Independent Bible College founded in 1896, in Greenville, SC. In ministry partnership with International Pentecostal Holiness Church.

- IHOPU Schools at the University include Forerunner School of Ministry and Forerunner Media Institute. Affiliated with Friends of the Bridegroom International and the International House of Prayer. In Kansas City, Missouri.

- IMI School of Ministry and Music

- Institute For Strategic Christian Leadership offers undergraduate and graduate levels classes in several regional campuses throughout the east coast.

- International Children’s Ministry Institute Campus in Litchfield, Illinois. Regularly conducting overseas schools in Russia, India, Thailand, and several African nations.

- Jacksonville Theological Seminary and Revelation Message Bible College

- Jubilee School of Ministry ministry training school by Jubilee Christian Fellowship in Fairfield, Iowa.

- The King’s College and Seminary Founded by Pastor Jack Hayford

- Kingswell Theological Seminary “Equiping leaders to build healthy churches and engage contemporary culture.”

- Latin American Bible Institute — Texas Assemblies of God residential institute in San Antonio, TX. Courses are offered in both

English and

English and  Spanish.

Spanish. - Latin American Bible Institute — California Assemblies of God residential institute in La Puente, California.

Bilingual and bicultural theological education.

Bilingual and bicultural theological education. - Lee University Affiliated with the Church of God in Cleveland, Tennessee.

- L.I.F.E. Bible College Pentecostal/Charismatic Bible college founded in 1923 by Aimee Semple McPherson. Affliated with the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

- L.I.F.E. Bible College East In Christiansburg, Virginia. Affliated with the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel.

- Maryland Bible College & Seminary in Baltimore. Affiliated with Greater Grace World Outreach.

- Masters Commission USA The founding Masters Commission at Phoenix First Assembly of God.

- Master’s Institute operated by the International Lutheran Renewal Center

- Messenger College in Joplin, Missouri. Part of the Pentecostal Church of God.

- Metro Jackson Master’s Commission “This is a 9 month program for intense training to be a closer follower of Christ.”

- Ministry Training College residential training institute of Christian International Ministries, founded by Bill Hamon. Campus is in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida.

- Minnesota Graduate School of Theology

- Miracle Valley Bible College & Seminary Pentecostal Bible College and Seminary founded in 1958 by A. A. Allen.

- Monterey Bay Calvary Chapel Bible College extension campus at Calvary Chapel Monterey Bay in Monterey, California.

- MorningStar School of Ministry

- National Bible College and Seminary in Ft. Washington, Maryland.

- Native American Bible College Assemblies of God.

- New Beginnings School Of Ministry in Lawrenceville, Georgia.

- New England Foursquare Bible Institute Offering a diploma in Biblical Studies, taught by experienced local pastors. Classes are held at area churches, headquarters in Uxbridge, MA.

- New Hope Christian College New Hope Christian College in Eugene, Oregon and Pacific Rim Christian College in Honolulu, Hawaii are becoming one college in two locations: NHCC Eugene and NHCC Hawaii

- New Life Bible College in Cleveland, TN. Where “the bible is the only textbook used in the classroom.” Part of Norvel Hayes Ministries.

- New York Calvary Chapel Bible College extension campus at Harvest Christian Fellowship in New York City.

- North Central University in Minneapolis, Assemblies of God. Carlstrom Deaf Studies.

- Northwest College in Kirkland, WA. Assemblies of God.

- Old Bridge Calvary Chapel Bible College extension campus at Calvary Chapel Old Bridge in Old Bridge, New Jersey.

- Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

- Oregon College of Ministry a Foursquare Bible college formerly known as East Hill Institute of Ministry, in Gresham, Oregon.

- Patten University An interdenominational Christian liberal arts college in Oakland, CA. Affiliated with the Church of God (Cleveland, TN). Founded by Dr. Bebe Patten.

- Payne Bible College Founded in 1970, affilated with Christ International Churches. In Mississippi.

- Pillsbury Institute of Applied Christianity Based in the St. Louis, Missouri area, offering on-campus and distance learning programs. Member of ACEA.

- Pinecrest Bible Training Center An interdenominational, Full Gospel Bible school, in Salisbury Center, New York.

- Portland Bible College Church-affiliated college offering two and four-year degrees. Sponsored by City Bible Church, Frank Damazio, Pastor. Member of ACEA.

- Radical Change Bible College Online and local classes from Kissimmee, FL. Jason writes: “This fullgospel/charismatic school offers ministry degrees based on ministry experience and also trains in ministry. They have blessed me and my ministry vision.”

- Regent University Virginia Beach, VA.

- Rhema Bible Training Center Word of faith Bible institute in Tulsa, Oklahoma, founded by Kenneth Hagin.

- River City School of Ministry part of Family Christian Center in Orangevale, CA.

- River of Life School of Ministry In Rusk, Texas. Offering a two year Bible School program that trains students in missions, pastoral care, children’s and youth ministry, and worship.

- Samuel E Walker School of Ministry

- School of Bible Theology Undergraduate/Graduate Pentecostal Seminary affiliated with the Pentecostal Assemblies of God of America.

- School of the Local Church In Tulsa, Oklahoma. Founded by Bob Yandian.

- Seattle Bible College “Where emerging leaders are transformed and equipped to change their world for Christ.”

- Simpson University in Redding, CA.

- Spirit Fire World Outreach School A church ministry school in Titusville, Florida.

- Southeastern College in Lakeland, FL. Assemblies of God.

- Southwestern Assembly of God University of Waxahachie, TX. Assemblies of God.

- Southwestern Christian University Formerly Southwestern College of Christian Ministries, in Bethany, Oklahoma. Affiliated with the International Pentecostal Holiness Church. See alsoGraduate School of Southwestern Christian University

- St. Michael’s Seminary A ministry of the Charismatic Episcopal Church.

- South Texas Bible Institute

- Texas Bible Institute

- The Call School a division of Wagner Leadership Institute

- Trinity Bible College in Ellendale, ND. Assemblies of God.

- Trinity Episcopal School of Ministry

- Trinity Life Bible College in Sacramento, CA

- Tucson Theological Seminary Classroom and internet classes.

- University of the Nations in Kona, Hawaii. Part of Youth With A Mission (YWAM). Programs include: Colleges of Communication, The Arts, Christian Ministries, Counselling & Health Care, Education, Science and Technologies, and Humanities and International Studies. There are also Discipleship Traning Schools for young adults and families as well as a

Korean Discipleship Training School.

Korean Discipleship Training School. - Urban Harvest Theological Seminary

- Valley Forge Christian College in Phoenixville, PA. Assemblies of God.

- Valor Christian College Formerly known as World Harvest Bible College, founded by Pastor Rod Parsley.

- Vanguard University in Costa Mesa, CA. Assemblies of God. (Formerly Southern California College)

- Victory Bible Institute a ministry of Victory Christian Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Founded by Billy Joe Daugherty.

- Victory School of Ministry operated by Victory Life Fellowship (Foursquare) in Ada, Oklahoma.

- Vineyard Leadership Institute Learn hands-on in this two year program in the context of a local church. Part of the Vineyard Church of Columbus.

- Wagner Leadership Institute Institute of practical ministry founded by C. Peter Wagner

- West Angeles Bible College Ministry school of West Angeles Church of God in Christ.

- Western Bible College of the Assemblies of God. In the Phoenix-Tucson area.

- Word and Spirit Institute Pentecostal Bible institute operated by Puget Sound Christian Center in Tacoma, Washington.

- World Center School of Ministry

- World Revival School of Ministry

- Youth With A Mission Search for Discipleship Training Schools Find up-to-date listings of ministry training opportunities worldwide. See also YWAM’s University of the Nations website.

- Yellowstone Valley Bible Institute operated by Faith Chapel (Foursquare) in Billings, Montana.

Molokans among the first to speak in tongues in America

Were Molokans the first to Speak in Tongues at Azusa?

By Andrei Conovaloff American Molokan Dukh-i-zhiznik (lit. living in the Spirit) oral history (documented in the Book of the Sun: Spirit and Life, Dukh i zhizn’) reports that Molokani and Pryguny received the “outpouring of the Holy Spirit” in the Milky Waters region (now in Ukraine) in 1833. The diary of Vassili V. Verestchagin documents that Pryguny (lit. leapers) in…

The Forgotten Azusa Street Mission: The Place where the First Pentecostals Met

By Cecil M. Robeck, Jr. For years, the building on Azusa Street has also been an enigma. Most people are familiar with the same three or four photographs that have been published and republished through the years. They show a rectangular, boxy, wood frame structure that was 40 feet by…

First Pentecostal Missionaries to Bulgaria

By Dony K. Donev, D.Min. Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals (Research presentation prepared for the Society of Pentecostal Studies, Seattle, 2013 – Lakeland, 2015, thesis in partial fulfillment of the degree of D. Phil., Trinity College) Interestingly enough, the arrival of the first Pentecostal missionaries to…

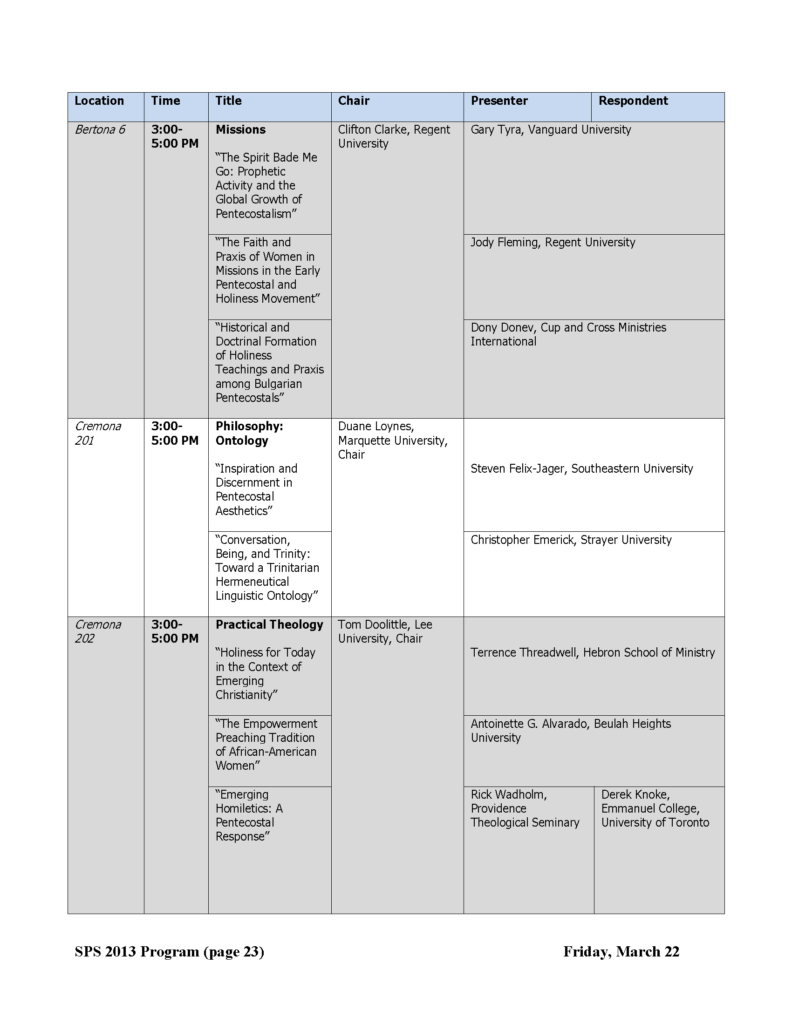

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle Pacific University on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

March 10, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under News, Publication, Research

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

Creating Web Identity for Ministry

For the past 20 years, our team has envisioned and created web communities around the globe, as a part of our ministry and in helping churches and Christian organizations build their internet brand and web identity. Here are just several examples:

- Missionary video sharing website (WorldMissions.TV)

- Social network community for the Church of God (ourCOG.org)

- Networking platform for Biker Churches (BikerChurch.US)

- Bulgarian Evangelical Church of God in Chicago (BGnewLIFE.com)

- LaFrance Church of God (LaFranceCOG.com)

- Bulgarian Christian Church in Las Vegas (LasVegasChurch.TV)

Furthermore, we have contributed to various churches and organizations through:

- Hosting our annual X Event for youth exploring the role of internet for youth and youth ministries in the 21st century

- Lecturing on WebMinistry 2.0 for Churches at the Leadership Development Institute

- Guest speaking at the BibleTech conference organized by Logos Bible Software

- Publications on web branding for churches and non-profit organizations

In the country of Bulgaria alone, our team envisioned and created the largest Bible internet community with:

- Dedicated Bible Study website (Bibliata.com)

- Christian video sharing community (Bibliata.TV)

- Bulgarian Christian social network (Bibliata.net)

- Bulgarian Video Bible (Bibliata.mobi)

See also how we help churches grow through:

Consulting and Coaching

Empowered by the vision for a continuous revival within the church of the 21st century, we have chosen to make the mission of our work this one statement: We help churches grow.

One of the approaches we have taken to accomplish this ministry goal is Consulting and Coaching:

- We have successfully worked with over 50 churches toward their effective missions programs and growth through (1) leadership training and team building seminars, (2) in-depth case study of church and ministry evaluations and (3) implementing individually designed strategies for ministry development

- Currently, our team provides continuous education to over 200 church leaders and ministry teams around the world through teaching and lecturing on a weekly basis along with daily prayer support

- We extend our efforts toward church growth by helping build strong family connections through relations counseling and parenting classes implementing play therapy as Board Certified LPC

Beside personal presence and team building strategies, we implement the media in virtually every approach of ministry. We have published several research monographs as well as film series about our ministry work. Our team holds a weekly TV program called the Bible Hour. (Learn how we help churches build their own and unique web presence)

See also how we help churches grow through:

Research and Teaching

May 1, 2012 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, Media, News, Publication, Research, Video, What we do

Empowered by the vision for a continuous revival within the church of the 21st century, we have chosen to make the mission of our work this one statement: We help churches grow.

One of the approaches we have taken to accomplish this ministry goal is Research and Teaching:

- Our historical research through the years has examined the archives of leading Pentecostal movements like the Church of God and Assemblies of God, British and Foreign Bible Society Archives at Cambridge University, Harvard University Archives, Southern Baptist Historical Archives, Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley, as well as various original Bulgarian and Russian sources

- In the area of chaplaincy we have worked with various government agencies, US Army commanders, NATO chaplains and Special Forces representatives in establishing the Bulgarian Chaplaincy Association comprising over 100 active Bulgaria chaplains and founding the first ever Masters’ in Chaplaincy Ministry Program in Europe

Beside personal presence and team building strategies, we implement the media in virtually every approach of ministry. We have published several research monographs as well as film series about our ministry work. Our team holds a weekly TV program called the Bible Hour. (Learn how we help churches build their own and unique web presence)

See also how we help churches grow through:

Evangelism and World Missions

Empowered by the vision for a continuous revival within the church of the 21st century, we have chosen to make the mission of our work this one statement: We help churches grow.

One of the approaches we have taken to accomplish this ministry goal is Evangelism and World Missions:

- We have ministered for over 30 years now on three continents, 25 U.S. states, Canada and Mexico (Map of our global ministry)

- We have spent seven consecutive years in missionary work in Bulgaria ministering to over 300 local congregations (Map of our ministry in Bulgaria)

- Since 1990, we have helped in the planting and team training of over 25 churches in Bulgaria as well as the Bulgarian congregations in Chicago, Houston, Las Vegas, San Francisco, Atlanta, London, Spain, Cyprus and Palma de Mallorca

Beside personal presence and team building strategies, we implement the media in virtually every approach of ministry. We have published several research monographs as well as film series about our ministry work. Our team holds a weekly TV program called the Bible Hour. (Learn how we help churches build their own and unique web presence)

See also how we help churches grow through:

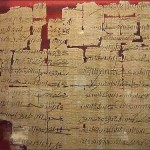

Investigating Ireland

Back in 2006, while presenting a paper on the Story of the Bulgarian Bible at the Evangelical Bible Society in Washington, D.C., we were invited to visit an exposition at the Smithsonian that was showing, among other ancient writing, the Codex Sinaiticus. To stand by this most ancient holistic text of the Bible, that so many hands through history have beheld with reverence, was an experience that is hard to describe. Fortunately, only a few months after our observation of the text, the University of Leipzig in Germany finished its long-overdue project with the text and its digital representation was made available to all via the internet. But just recently, we were privileged to take a research trip to another, yet older and more revered Bible text, namely the Chester-Beatty papyri in Dublin.

What a person is most surprised of while visiting the Chester-Beatty library is how easy it was to find and access these ancient writings. Starting at the heart of Dublin, one goes south toward the river on O’Connell Street by the big statue of the famous Irish politician and patriot Daniel O’Connell. After crossing the river on the O’Connell Bridge by Abbey Theater, you will reach the infamous Trinity College and the House of Lords by the Bank of Ireland. The Dublin Castle is less than a mile walking up the hill west on College Green and behind the castle, by the uniquely shaped garden, is the Chester-Beatty library. Right next to the castle is the City Center, across the street is Christ Church Cathedral and just a block away is the St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The Chester-Beatty papyri of the New Testament are displayed in the center of a magnificent exposition of ancient writing on the second floor on a pyramid shaped platform. A closer look at the papyri surprises the observer with their miniature size (only as big as an iPhone). The color of the pages has darkened through the centuries of their history to a dark almost brownish ocher. The small font of the equally justified text has faded to brown. Since the papyri were bound as a codex, instead of the traditional roll format, they are badly burnt at the end of the pages and in the center where the pages were attached together.

Three of them, marked P45, P46 and P47, are specifically important to the subject of New Testament criticism being the oldest copies of the New Testament dated at 200-250 AD beside P52, which is dated around 150 AD. In 1931, the director of the British Museum, Sir Frederic Kenyon reported for The Time that their discovery of the Chester-Beatty papyri is only next to the Codex Sinaiticus.

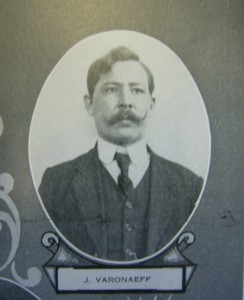

The (un)Forgotten: The Story of Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s Children

Our presentation at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis opened a door for discussion of early missionaries to Eastern Europe with a special focus on Rev. Ivan Voronaev. But the story and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev cannot be separated from his main supporter and partner in the ministry – his wife and children.

Our presentation at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis opened a door for discussion of early missionaries to Eastern Europe with a special focus on Rev. Ivan Voronaev. But the story and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev cannot be separated from his main supporter and partner in the ministry – his wife and children.

During the time of original research, it became obvious that Ivan Voronaev was successful in the ministry both in the United States and Europe only through the obedience of his family. They followed his call for missions, leaving behind the comfort of life in America. The Voronaevs sacrificed the future of their children for the unknown reality of Russia’s greatest depression. The strive for survival followed the imprisonment of both parents along with the virtually impossible task to re-immigrate from Russia and reunite in the United States, and the constant struggle to save their parents from certain death in Stalin’s consecration camps even when all hope was lost.

The Voronaevs’ story presents an early historical case study on Pentecostal missionaries and their children, not only as second generation believers, but as second generation Pentecostal immigrants as well. This example is particularly interesting since it combines both mission and immigration, as integral parts of the Pentecostal identity at the dawn of the movement. To add to this there is the relationship between missionary families and the mission-sending agency, on this occasion being the Missions Department of the Assemblies of God and in part the Russian Evangelical Diaspora.

In this context, the research on the Voronaev family has three distinct parts: (1) life in Russia and the imprisonment of the parents, Ivan and Katherine Voronaev, (2) back to America under the care of Assemblies of God Missions’ Department and (3) and the after years, with a special focus on the life and ministry of the oldest of the Voronaev’s children, Paul.

The research will utilize the available archive information at the Assemblies of God archives in Springfield, MO, as well as some Russian library material from Moscow and Kiev, which have become available after the presentation of our 2010 Voronaev paper. Special attention will be given to Paul Voronaev’s personal correspondence after his return to the United States and subsequent papers, relative to the story of the Voronaev’s children, published by him in later years. As Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s personal end is yet unknown, it is our hope that story of the Voronaev children, will provide a much needed closure to the life and ministry of one of the earliest Eastern European missionaries in Pentecostal history.