A Primer to Postmodernism

![post-modernism[1]](https://cupandcross.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/post-modernism1.jpg) A Primer to Postmodernism doesn’t defend or reject postmodernity, but simply attempts to provide a clear understanding of it in a primer-like manner. The primer-like approach along with the Star Trek parallel reminds the reader of the alter A Primer to Postmodernity (1997) by Joseph Natoli. Grentz’s book does, however, approach postmodernity from an evangelical point of view as it examines its effect on and possible dangers for the evangelical church.

A Primer to Postmodernism doesn’t defend or reject postmodernity, but simply attempts to provide a clear understanding of it in a primer-like manner. The primer-like approach along with the Star Trek parallel reminds the reader of the alter A Primer to Postmodernity (1997) by Joseph Natoli. Grentz’s book does, however, approach postmodernity from an evangelical point of view as it examines its effect on and possible dangers for the evangelical church.

Grentz approaches postmodernity as a present reality. Intellectual mood and cultural expressions forming the future of the world thought by abandoning the Enlightenment belief of progress that transforms the modern mindset with a new ever-changing identity (p. 13). Grentz’s first supporting evidence deals with the Star Trek culture. Star Trek is compared to the futuristic and informational outlook of postmodernism, which later in the book will pay a major role in explaining the phenomenon. However, while such example is proven to be a good approach in an American context, it may not have the desired effect and understanding of people from other cultures where postmodernism is also taking place. The dangerous assumption that Start Trek equals postmodernity may not be safe where Star Trek is culturally limited or even unavailable.

The primer continues with examination of ethos and culture and how postmodernity both emerges from them and transforms them. Grentz singles out the arrival of the information era as the factor, which once catalyzed by modernity, has become the status parallel of the complete realization of postmodernity. In this discussion important evidence are examples from culture, architecture, media and everything which modernity lifted up as indicators of modern progress. Especially prominent for the author is the use of movies and television among other media. He properly and almost prophetically recognizes their major role in postmodernism, regardless of the fact that at the time of the writing of the book typical postmodern movies like The Matrix, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings and even The Passion of Christ had yet not been released.

The media industry brings space and time into eternal here-and-now (p. 32). Now that all of the above have proven to be insufficient answers to one’s search for identity and reality, postmodernity steps in by saying we all gave our stories and we are all entitled to our truth, our reality and our point of view. As a result, the image of the screens blurs the difference between the “subjective self and the objective world” (p. 35). Reality is no longer what it really is, but the virtual present can make it what we want it to be.

The collapse of modernity brings changes in the world view where postmodernity denies commonly accepted metanarratives and social structures by claming that everyone can have his/her own world view (p. 39ff). Grentz proposes that the reason for such an imaginative displacement is within the foundations of modernity and the Enlightenment (p. 57) with a special accent on Kant’s philosophy (p. 73). This is followed by discussion on metanarrative rejections, scientific method critique and objectivity in general and the influence of relativity.

In this part Grentz includes a discussion on language and its word component, as formative elements of the metanarrative. This subject is important since postmodernity sees reality as a gap between what we say about reality and its actuality (between our representation of reality and reality itself). Since words and world are linked through personal and cultural frames, reality is always in motion. The clash between different metanarratives begins a quest for agreement between word and world which redefines the meanings and value of things. However, because there are multiple connections between word and world, different metanarratives can create different realities. Postmodernity reserves the right of every individual of a metanarrative to describe one’s own reality. Grentz’s historical and philosophical overview of postmodernism finds a proper conclusion with prognoses for the future. This drafts the contours of a post-modern gospel with the following characteristics:

Post-individualistic – focusing on community and not only on the individual.

Post-rationalistic – relating the gospel message not to the intellect only, but to the whole human being.

Post-dualistic – similar to the post-rationalistic provides it holistic ministry to the human being not separating it to a body and a soul.

Post-noeticentric – understating one’s goal of not simply having knowledge, but the process of attaining wisdom.

The post-modern gospel is part of Grentz’s attempt to providing clear directions of how Evangelicals can relate to postmodernism and at the same time not allow it into change their identity. For the Christian church, postmodernity becomes a stage of post-Christendom where values and metanarratives are rejected and replaced by a personal interpretation of life varying from a general social condition to an aesthetic ideology or cultural style. Grentz recommends that our intent should be to reject the rejection of metanarratives, since our faith is based on Biblical narratives. In conclusion, the book proposes using the anti-modern character of postmodernity. The text provides little recognition of pre-evangelical religious groups like Pentecostals whose genesis was an opposition to modernity.

Mission Applications: Post-Communist Believers in a Postmodern World

The Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 opened the a door toward Eastern Europe and the Soviet republics. This liberation opened a door for the entering of postmodernity as well. This process unavoidably altered the context in which Bulgarian Pentecostalism existed and operated formed three-cycle critical problem in ministry as follows:

Momentum: The Bulgarian Revival of the 1990s created an unprecedented opportunity for Bulgarian Protestantism. Never before (even in Orthodox Christian history) had a revival movement of such dimensions and capacity swept through Bulgaria involving not only believers and churches, but unbelievers and communities. Unfortunately, just as perpetuum mobiles of the second kind do not exist, spiritual momentum cannot continue without a source of energy. Fifteen years later, standing in a brand new millennium and ever-changing social formations, the Bulgarian Protestantism was at the verge of losing the momentum created by the 1990s revival. The reason may be a very simple one: lack of preparedness.

Community: Since education and training for the ministry were very limited and almost primitive during the Communist Regime, after the Fall of the Berlin Wall very few Protestant leaders realized the need of a new paradigm for ministry. In many cases for over ten years an underground model of theology, church and mission was used only to prove time after time its incompatibility to the new social order. Efficiency was the least among the worries because even within churches using working and progressive models for ministry splits occurred. It was soon realized the strong church communities which existed under the pressure of Communist persecution were not able to fully implement the new democratic freedom.

Identity: Most of the above described splits arose not so much from arguments of how to work, but from differences of who we are. The change from underground to democratic styles of worship gave a multitude of opportunities for self-actualization through which it was soon realized that church which was united under the persecutions, acted quite differently in the context of democracy. This soon led to a search for original identity applicable to both the individual believer and the Christian community.

However, revival has not stopped. While many consider that a number of new converts have left the church in the past five to seven years, an even greater number has joined the church leaving the balance, at least for now, on the plus side. Such phenomenon clearly determines that the problem which Bulgarian Protestantism is facing is not in evangelism but in discipleship. Thus, as revival goes on, it is certain that it must affect not only evangelism but the disciple-making process as well.

The Missional Church

The nature of the church is missional, through the fact that its existence is powered by the Great Commission. The book summarizes the culture of today’s American spirituality and its relation to the apostolic church. The main question is, “What would a theology of the church look like that took seriously the fact that North America is now itself a mission field?”

The nature of the church is missional, through the fact that its existence is powered by the Great Commission. The book summarizes the culture of today’s American spirituality and its relation to the apostolic church. The main question is, “What would a theology of the church look like that took seriously the fact that North America is now itself a mission field?”

Five Key Insights

1. The missional nature of the church – The place which the church takes in the surrounding world/society defines its nature as missional. How it interacts with the surrounding worlds identifies the church’s response to the needs of individuals and groups of people and results in its success/failure to fulfill its original mission. A valid point was the statement that the witness of the missional church is characterized by its integrity.

2. Recovering missional identity – Recovering the church’s original New Testament identity has been a subject of discussion for many various ages in church history. The volume of works written about it has indeed increased in the latter part of the 20th century. The discussion in the book claims that as truth, self, and society are rediscovered in postmodernism, the churches of North America will recover its missional identity. Thus, the individual search of identity will reflect on the corporate search of the church as a community and as the Body of Christ. Chapter four further claims that the churches missional identity is shaped by the gospel of the reign of God which Jesus preached.

3. The Holy Spirit and the community of the missional churches – The Chapter on the Holy Spirit, although very informative, did not integrate the connection between the Spirit and Missional outreach to a practical paradigm, but it was mostly a theoretic and philosophical proposition.

4. On spiritual leadership – the discussion on spiritual leadership is based on the axiom that leadership is focused on the reign of God. Only then the church assumes its mission. Solving problems and creating unity within the church is reached through the same focus on the reign of God.

5. The secular surroundings – the vision of the church may not align with the secular surrounds. Actually, it may often completely contradict them fulfilling its role as a prophetic utterance. At the same time, social, political and economical factors may oppose the message and the mission of the church, thus creating an atmosphere in which the church grows against the grain.

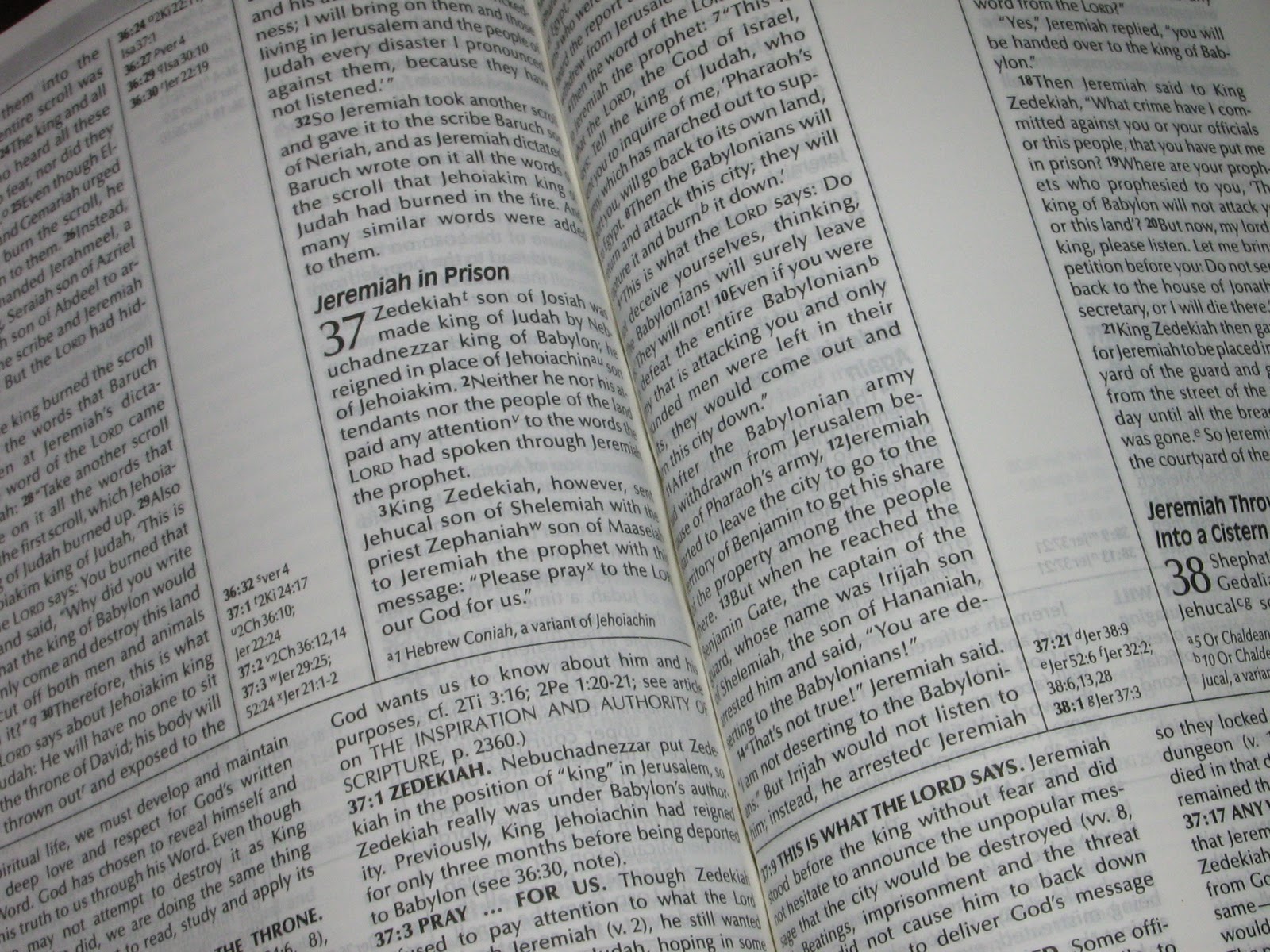

The Fire Bible Review

Several months ago, our team undertook the task of comparing and reviewing a growing number of Study Bibles appearing on the book market recently in what we called a 21st century Revival of Study Bibles. This article is part of our Study Bibles review series as outlined here: https://cupandcross.com/bible-revival/

Fire Bible Review

Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

I’ve been personally following and using the Fire Bible since it was called the Full Life Study Bible. And not mainly because it is Pentecostal (much like Dake’s and Spirit Filled Life Bibles), but more so because a good portion of the commentaries were written by one of my favorite professors in seminary, Dr. French Arrington. Therefore, I was very truly blessed when our ministry was able to participate in the translation and promoting this great work in Bulgaria.

Beginning with our usual control passages from the Old Testament, Number 6 contains a great detail of explanation on the vow and practice of the Nazarite law. Furthermore, there is a special note on “Wine in the Old Testament” in the Fire Bible, and the Aaronic benediction at the end of the chapter is specifically marked, outlined and discussed as two articles are cited in connection with “Faith and Grace” and “The Peace of God.”

Our second control passage in Jeremiah 18 is also not left without discussion. Actually, the commentary in v.8 makes two powerful points on God taking account spiritual changes in our lives and not forcing our decision despite knowing the final outcome; thus presenting a typical Pentecostal approach on free will, God’s sovereignty and foreknowledge, which is further discussed in the article on “Election and Predestination.”

The doctrine of the Rapture is not only mentioned in Revelation 4, but preceded with a special article from 1 Thessalonians and a detailed chart of Last Day Events in the forward of Revelation in both the early and the Fire editions. The Tribulation is also clearly explained as a post-Rapture event, divided in two parts and well documented with Scripture references. Additionally, in a very balanced Pentecostal manner, the dispensations, although noted by some, are not explicitly defended in the pre-Millennial system. The significance of the phrase “in the Spirit” is dully noted, which brings us to Pneumatology.

In regards to Pentecostal theology, the doctrine of Trinity is presented in an indictable orthodox way after the Athanasius Confession. Perhaps, the only criticism could be that there’s no mention of the fact that some early Pentecostal groups indeed taught Jesus-only doctrine. The Holy Ghost baptism is both theoretically and practically explained in the forward to Acts, while there’s an additional article on Speaking in Tongues after Acts ch.2. This is further mentioned in a comment after Mark ch. 16 followed by an article on Spiritual Gifts in 1 Corinthians 12.

There’s also a detail discussion the doctrine of Sanctification in 1 Peter after the foreknowledge of God is additionally explained. Sanctification is viewed as immediate, not “giving up sin little by little,” yet “do not suggest an absolute perfection.” The work of God and man is defined, and most importantly God is viewed as one who desires to sanctify His people. There’s no specific comparison to a second work of grace, yet the general approach toward the doctrine and practice of sanctification presents a typical, historically accurate, Pentecostal point of view toward the teaching.

The Four Gospels of the New Bulgarian Translation Published

August 15, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication, Research

We are both happy and humbled to announce the publication of the Tetraevangelion of of the New Bulgarian Translation including:

- Matthew (2011)

- Mark (2010)

- Luke: Gospel and Acts (2013)

- John: Gospel, Epistles and Apocalypse (2007)

This final volume has been almost ten years in the making as it combines all four previously published volumes. It is new literal translation in the Bulgarian vernacular directly from the Nestle Aland Novum Testamentum (27/28 editions).

We thank friends and foes for the internal motivation without which this work would have never been completed.

We are currently working on another similar project, namely the publication of a Study New Testament in Bulgarian, which will be ready for print by the end of this summer.

Christ and Culture

Richard Niebuhr is one of the most influential modern reformed theologians. He is considered an authority on ethics and church in the Western culture and writes that the authenticity of the Christian faith is based on its realization in a counterpart world setting.

Christ and Culture presents an observation of the ways the church realizes its place in the surrounding world. The central idea of the book is that the church wrestles with both its Lord and with the cultural society with which it lives. In such context, the relevancy of the church’s message to the opposing party remains the central as well. Four models of how the Christian and contemporary realities can interact to seek the answer to how Christian life should be lived are discussed.

Niebuhr approaches culture in general, from a reformed point of view with a definite accent on the present (now) covenant and not so much with apprehension of the eschatological future of the church. His views are based on a mid-twentieth century church operating in a modern Western context. His discussion of the relationship of church and contemporary culture, however, give an opinion much beyond this time making this research valid today.

Niebuhr, believed that the life which Christ commanded from his followers contain values that are essential for the formation of culture and are much needed by the secular world. Christian faith, however, needs to be brought beyond self-separation in order to engage culture with the values of the Christian life. Faith then acts more as a social presence and action which become a transforming factor for society. In a typical reformed manner, the text proposes the church’s involvement in bringing the Kingdom on earth.

The author then uses the four models to examine the variations of the place in culture given to Christ and examines the different effects on society and the church. These models are: (1) Christ against, (2) Christ of, (3) Christ above and (4) Christ transforming culture. They form a literal gradation in the book and serves as the author’s supporting evidence. Christ against culture is a rather “postmodern” approach through which the church rejects modern culture. Such process is in parallel with the life of Christ who not only taught the values of faith but also lived them. Thus, as the church opposes the world, Christian values must become personal acts rather than theoretical descriptive qualifications.

Niebuhr explains that Christ’s rejection of culture was not a result of eschatological expectations, but a result of Him being the Son of God. The realization of Christ’s sonship, then is also the way through which the church should minister in the world. In other words, the church and the life of the Christian must demonstrate Christ’s sonship.

Niebuhr outlines several theological problems in the Christ against culture model as follows (1) reason and revelation, (2) nature and prevalence of sin, (3) relationship of law and grace and (4) the relationship of Jesus Christ to the Creator of nature and Governor of history.

Christ of culture is the second approach which Niebuhr observes. This is another historical overview which speaks much of the Enlightenment. The text discusses several of the thinkers of the day, who attempt to identify Christ with culture. This model shifts the focus from revelation and reason to Christ and culture, as shown in the discussion about Rischl.

The difficulty with cultural Christianity is that it has always been widely rejected. As far as discipleship is concerned, such approach is not more effective than Christian radicalism. The reason for this is that Gnostics and cultural Protestants which Niebuhr describes as lead representatives of this approach create a new mystical image of Christ. When paralleled with the actual Christian story, such images cannot bear the witness of true Christianity and are rejected by both the Scripture and Church.

Christ above culture is the next model which Niebuhr examines, treating medieval representations of a practical synthesis. This synthesis was full of tensions as both sides of the church were corrupt. Regardless of the damages, they both served as means for each other transformation, thus reforming each other. Such synthesis could not be a present day paradigm except if its prerequisites, protesting Christianity and religious institutions, are present in the context of a cultural church able to accommodate such relationship.

The final proposal is the one of the culture-transforming Christ. Unfortunately, this chapter is not as comprehensive as the rest of the observations, perhaps leaving some space for new research and answers. The author spends a great deal of time examining the conversion motif from the fourth Gospel as a model for this culture-transferring Christianity. He then relates it to the theology of Augustine and Maurice and their views of culture transformed by Christ.

In conclusion of this reflection, it must be pointed out that while precise in a great deal of historical facts, Niebuhr is not accurate in the description of the Mennonite Church (Christ Against Culture), perhaps he meant Amish. Also, the definition of culture seems to change through the presentation of different models. Finally, he approaches the relationship of culture and Christianity from a Calvinistic point of view, leaving very little expression of other paradigms outside reformed theology.

Mission Applications

The Fall of the Berlin Wall opened the door toward Eastern Europe and the Soviet republics. Since millions of Eastern Europeans coming out of the Communist Regime could relate to the Pentecostal faith, the numbers of saved and baptized with the Holy Spirit grew by the millions. The result was a multitude of revival fires from the Prague to Vladivostok which unavoidably began changing the local culture.

In the midst of the Pentecostal Eastern European revival, the underground and semi-underground Pentecostal churches coming out of the communist persecution quickly found themselves insufficient to accommodate the need of the new converts for a Pentecostal community. Having had minimal opportunities for education and training under Communism, the only hope was in the supernatural. I In such times, lack of spiritual dependency was replaced by human leadership, self-confidence and wrongful ambitions. Ministers, churches and whole denominations made mistakes which resulted in thousands of new converts being lost for the harvest. Adding clearly Western theological views, church practices and management models were only temporary patches. Like its context of origin, they lasted only enough for the problems to grow and come back in a hunt to destroy human lives. Intense opposition from the schismatic Eastern Orthodox Church, severe economical crises, the lack of political direction, rapidly changing governments and laws were only a few details present as we entered Postmodernity. All of a sudden theologies brought from he west made no sense in the Eastern European context and a sudden need for a new, contextualized Pentecostal paradigm for ministry emerged.

The main question which such paradigm must answer is how a post-persecuted and post-communist church ministers to a postmodern world. In Chrsit-cultural terms, this same question may sound like, “How does a church which has been rejected by Community culture for decades now overcome this rejection and minister to the post-Communist culture.” The answers are many, but the right one must emerge form the identity of the church through a realization that even before there ever was a post-Communist culture in Bulgaria, through rejection of the Communist culture, the church itself was operating within a post-Communist reality. Such paradigm is not strange to the Bible, as the Early Church rejected the Roman reality and operated, similar to a post-Roman reality. The problem with the Bulgarian Protestant church, however, is a very oxymoronic one. This comes from the fact that while outsiders would consider Bulgarian post-Communist culture as a postmodern one, in fact the present Bulgarian culture is pre-modern or at best modern. Since the relationship between postcommunist and postmodern culture is still a new issue, the correct paradigm within such culture must make a decision if the post-Communist culture is pre-modern, modern or postmodern. Such paradigm for ministry will act as a paradigm of cultural transformation.

Spirit, Pathos and Liberation

The research presents Hispanic Pentecostalism as “the voice of the voiceless.” Solivan prepares the reader for the cultural and religious context in which orthodoxy has failed for various cultural, historical and theological reasons. He further proposes that the new term of “orthopathos” should be used. Orthopathos is the combination of orthodoxy (what we believe) and orthopraxis (what we do). As such, it introduces an interlocutor between God and humanity and between beliefs and works. God is the God who suffers for creation and with creation. The act of repentance is then the human response to the passion of God for humanity and joining with His sorrow in the death and alienation of mankind. Such appeal is against the dehumanization of revelation. It reduces the salvific experience to a simple claim of Biblical truths based on a logical choice.

The research presents Hispanic Pentecostalism as “the voice of the voiceless.” Solivan prepares the reader for the cultural and religious context in which orthodoxy has failed for various cultural, historical and theological reasons. He further proposes that the new term of “orthopathos” should be used. Orthopathos is the combination of orthodoxy (what we believe) and orthopraxis (what we do). As such, it introduces an interlocutor between God and humanity and between beliefs and works. God is the God who suffers for creation and with creation. The act of repentance is then the human response to the passion of God for humanity and joining with His sorrow in the death and alienation of mankind. Such appeal is against the dehumanization of revelation. It reduces the salvific experience to a simple claim of Biblical truths based on a logical choice.

Several reasons are given to prove that such intercalative paradigm is necessary for the Hispanic Pentecostal communities. Among them are not only Biblical, theological and mission requirements, but also sociopolitical, ecumenical and identity ones. These necessities expand the orthopathic approach beyond the church-religious context into the area of social transformation, thus proposing it as a larger paradigm for Christian mission to the world. Solovan claims that pathos denotes the idea of goodness and passion, which were very often missed by the ecclesial formations which followed the early church and was never properly restored by the Reformation. The discussion addresses the imago Dei and the pointed by Tertullian’s argument that God’s expression of passion is not a reflection of ours, but rather a reflection of His image.

Having established the pathos idea, Solivan goes further with showing how orthopathos can become a means of human liberation even through suffering. Three theological principles of orthopathos are presented as follows:

1. In connection with the Biblical principle of identification.

2. In connection with the Biblical principle of location.

3. In connection with the Biblical principle of transformation.

Through the Biblical foundation, the starting point of orthopathos is identified with the suffering and its relations to the category of poverty within the socioeconomic matrix. The author continues with a parallel between suffering and the work of the Holy Spirit and His work among the poor.

Once, the pneumatological factor is introduced, Solivan goes a step further to discuss Pentecostal glossolalia. He sees it as an affirmation of the work of the Spirit among the poor. This gives a Pentecostal conclusion of the orthopathos topic and allows the author to explore its practical implementation within the Hispanic Pentecostal community.

The book further introduces three critical questions concerning the topic of orthopathos. The first one is concerned with the imago Dei in reference to the emerging identity of Hispanic Americans and more specific Hispanic American Pentecostals.

The first concern is continued by the second question about the common experiences and culture in the context of North American immigration dynamics. This factor has a rather unicultural and ecumenical approach, but brings several interesting possibility for communality within the Holy Spirit. The third concern deals with the transformation of practice into praxis in a Pentecostal context and is connected with the last question which calls against passivity toward suffering and poverty. The book concludes with a call for social transformation which is addressed by Pentecostal theology and praxis.

Practical Implementation

In the background context of the treated problems and issues, the book inevitably stands against passivism toward social injustice and touches on the role of the church in the social transformation dynamics. Although, the book is dedicated to a Hispanic Pentecostals, the principles of social transformation are applicable also in my area of ministry in postcommunist Bulgaria. The similarities are many.

First, just like South America, Eastern Europe after the Fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 is struggling economically. Along with the social and political instabilities in the region, the economical crises have separated the Bulgarian community into a small percentage of extremely rich, and a majority of extremely poor with minimal or no middle class separation between them.

Second, while South America’s religion is monopolized by the Catholic Church, this role in Bulgaria has been occupied by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The last has been credited as the protector of the Bulgarian culture during the Turkish Yoke and the Communist Regime. However, in both cases, the Eastern Orthodox Church has participated in historical dynamics which have created environments for the rich and powerful minorities, thus oppressing the poor and the underprivileged majorities.

Thirdly, through the Protestant missions Pentecostalism was introduced to the Bulgarian culture in the 1920s. Today it is the fastest growing religious movement in Eastern Europe. Protestantism has rightly and faithfully fulfilled its role as a sociological factor in the formation of the Bulgarian culture exactly in the historical moments when the Eastern Orthodox Church has been or had chosen to become socio-culturally inactive.

Fourth, cross-cultural problems which Hispanic communities in North Amerca face are similar to the problems which Bulgarian immigrant communities face. The cross-cultural processes, struggle with identity, loss of heritage, as well as their recovery and reclaiming through the Biblical salvific experience, are dynamics which essential for the Bulgarian immigrant communities and the Bulgarian immigrant individually.

Finally, Pentecostalism has drawn a paradigm for personal and social transformation which has created an environment for liberation of the oppressed by postcommunist reality Bulgarians both in Bulgaria and internationally. It has further effectively addressed theological and practical issues through Pentecostal identity, experience and community becoming a factor within the social transformation and the postcommunist mentality as well. As such Pentecostalism, in a larger scale, has become an answer for many through providing answers to existential questions in the midst of crises, transitions and insecurity as its call for orthopathos has integrating the sacrifice of God with the present search and suffering of the Bulgarian nation.

20churches.com: Official Release

Comments Off on 20churches.com: Official Release

We are honored and humbled to introduce an innovative ministry instrument, which can increase your church influence in the community.

20churches.com is a FREE web tool that networks pastors with leading ministry experts to helping churches grow and prosper by increasing:

- Leadership reach and effectiveness

- Volunteer team building strategy

- Communicational and conflict resolution

- Mobile strategy as a church

- Web presence on the social networks

- Overall ministry’s vision and mission

The website’s algorithm analyzes church influence and reach within the community based on: (1) your survey results, (2) your local demographics and (3) leading ministry expertise combined with national church trends.

- Go to 20churches.com to see your current church influence

- Fill out the online survey to receive an instant free report

- Choose among leading experts to increase your church influence

Please leave your feedback as it will help us improve our methodology and assist others. You can also check the current national church trends at:http://20churches.com/trends/

This service is free. Your information is confidential and will not be used for offers or reselling. Click here to begin now: 20churches.com

#ourCOG Dev.Team

![logo-copy-600x238[1]](http://ourcog.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/logo-copy-600x2381.jpg)