Is Religion In America in Decline?

Duke University sociologist Mark Chaves’ working title for his new book on trends in U.S. religion was “Continuity and Change in American Religion.”

But the folks on the Princeton University Press marketing team suggested he could attract more attention with the bolder title: The Decline of American Religion.

Chaves, director of the National Congregations Study, took another look at research showing indicators of traditional beliefs and practices are either stable or falling in a nation that is a symbol of the staying power of religion in the West.

His conclusion: “The burden of proof has shifted to those who want to claim that American religiosity is not declining.”

Chaves shared his perspective in a paper on “The Decline of American Religion?” for the Association of Religion Data Archives. His work is a significant addition to the discussion of the future of faith in the U.S.

The argument that religion is declining has gained more attention in recent years with major surveys pointing to the existence of a substantial group of Americans who state no preference for organized religion.

Fifteen percent of respondents to the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey did not identify with a religious group, up from 8 percent in 1990. The 2007 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey found 16 percent of respondents said they were unaffiliated with any particular faith today, more than double the number who said they were not affiliated with any particular religion as children.

But researchers also point out strong signs of stability, even steady growth over the long term, in American religious life.

“The single most significant trend in American religion from 1900 to the present has been the steady and spectacular decline in the percentage of religiously unaffiliated people in the American population,” J. Gordon Melton, founding director of the Institute for the Study of American Religion in Santa Barbara, Calif., wrote in a recent ARDA paper on “American Religion’s Mega-Trends.” “In 1900, the religiously unaffiliated included some 65 percent of the population. That figure has now dropped to around 15 percent.”

Signs of decline

Chaves does not doubt the central role of religion in the lives of Americans.

“By world standards, Americans remain remarkably religious in both belief and practice. Americans are more pious than people in any Western country, with the possible exception of Ireland,” he said in the ARDA paper.

However, he noted, whether it is a major change such as a drop in the rates of religious affiliation or a small change such as the number of Americans who say they believe in God declining from 99 percent in the 1950s to 92 percent in 2008, no indicator of traditional religious belief or practice is going up.

“On the contrary, every indicator of traditional religiosity is either stable or declining. This is why I think it is reasonable to conclude that American religion has in fact declined in recent decades — slowly, but unmistakably,” Chaves said.

Those indicators of decline, taken from General Social Survey data, include:

- From 1990 to 2008, the percent of people who never attend religious services rose from 13 percent to 22 percent.

- Just 45 percent of adult respondents born after 1970 reported growing up with religiously active fathers.

- In the 1960s, about 1 percent of college freshmen expected to become clergy. Now, about three-tenths of a percent have the same expectation.

- The percentage of people saying they have a great deal of confidence in leaders of religious institutions has declined from about 35 percent in the 1970s to about 25 percent today.

An uncertain future

So what is the final verdict on the status of religion in America?

There may not be one.

Baylor University sociologist Paul Froese said the research seems to indicate a lot of stability in religion in America. In practical terms, Froese said, he does not see any trends that religion is declining in social or political influence in the United States.

When one considers major cultural changes in the United States on issues such as racial attitudes, “these religion indicators by comparison seem really stable,” he said.

Chaves said there is plenty of room for interpretation.

“Reasonable people can disagree on whether the master narrative is fundamentally decline or fundamentally stability,” he said in an interview.

What decline is evident has been gradual: “American religion remains very vibrant and will for your lifetime and my lifetime,” Chaves said.

Looking to the future, the aging of the U.S. population should be a positive influence on religion since religious beliefs and practices tend to increase with age, researchers say. But the declining participation by younger generations of parents is a significant negative predictor. In the National Study of Youth and Religion, having highly religious parents was one of the strongest variables associated with youth being highly religious as emerging adults.

So what is Chaves going to call his new book on religion in America when it comes out this summer?

“Bland or not,” Chaves says in the ARDA paper, “it will be called, “American Religion: Contemporary Trends.”

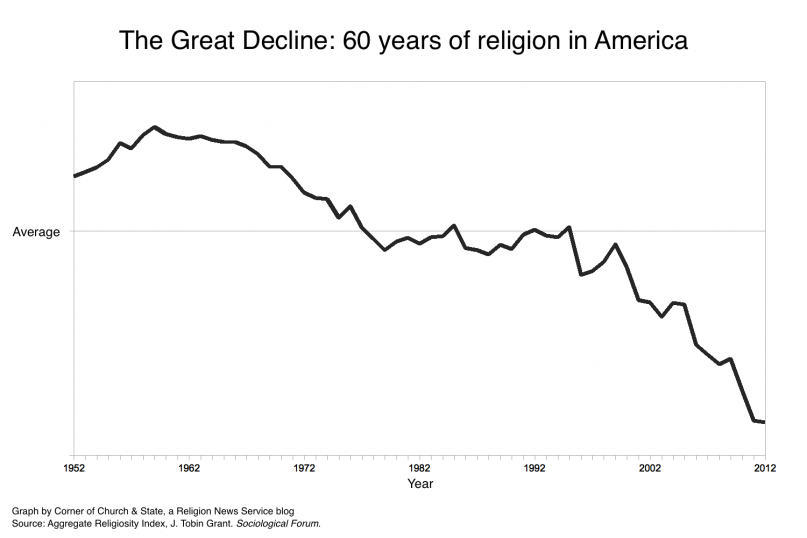

The Great Decline of religion in 60 years

Religiosity in the United States is in the midst of what might be called ‘The Great Decline.’ Previous declines in religion pale in comparison. Over the past fifteen years, the drop in religiosity has been twice as great as the decline of the 1960s and 1970s.

How do we track this massive change in American religion? We start with information from rigorous, scientific surveys on worship service attendance, membership in congregations, prayer, and feelings toward religion. We then use a computer algorithm to track over 400 survey results over the past 60 years. The result is one measure that charts changes to religiosity through the years. (You can see all the details here).

The graph of this index tells the story of the rise and fall of religious activity. During the post-war, baby-booming 1950s, there was a revival of religion. Indeed, some at the time considered it a third great awakening. Then came the societal changes of the 1960s, which included a questioning of religious institutions. The resulting decline in religion stopped by the end of the 1970s, when religiosity remained steady. Over the past fifteen years, however, religion has once again declined. But this decline is much sharper than the decline of 1960s and 1970s. Church attendance and prayer is less frequent. The number of people with no religion is growing. Fewer people say that religion is an important part of their lives. All measures point to the same drop in religion: If the 1950s were another Great Awakening, this is the Great Decline.

New Controversial Law on Religion to be Voted in Bulgaria

The Patriotic Front, a newly established political formation in Bulgaria, filed changes to the 2002 Religious Dominations Act last Thursday. The new measure bans all foreign citizens from preaching on the territory of Bulgaria, as well as preaching in any other language than Bulgarian.

The Patriotic Front, a newly established political formation in Bulgaria, filed changes to the 2002 Religious Dominations Act last Thursday. The new measure bans all foreign citizens from preaching on the territory of Bulgaria, as well as preaching in any other language than Bulgarian.

The draft amendments also foresee banning foreign organizations, companies and citizens from providing funding or donating to Bulgarian religious denominations. All the religious denominations in Bulgaria will be obliged to perform their sermons, rituals and statements only in Bulgaria. One year’s time will be given to translate religious books into Bulgarian.

Financially, the draft laws would ban not only foreign physical and legal entities from funding Bulgarian religious institutions, but also companies with foreign ownership that are legally registered in Bulgaria. Using state funding for “illegal activities” by religious denominations will be sanctioned with prison terms of three to six years. With these sanctions in mind, the new legal measure embodies the following rationale:

- Churches and ministers must declare all foreign currency money flow and foreign bank accounts

- Participation of foreign persons in the administration of any denomination is strictly forbidden

- Foreign parsons shall not be allowed to speak at religious meetings in any way shape or form especially religious sermons

- Anonymous donations and donorship to religious organization is not permitted

- Bulgarian flag shall be present in every temple of worship

- The new measure will block all foreign interference in the faith confessions and denominations in Bulgaria

June 2018 Update: Churches across Bulgaria have petitioned against the new changes in the Law of Religion as they constitute:

- Limitations on freedom of religion and speech

- Merge church and state

- Establish goverment control over preaching

- Ban any missionary work and preaching in a foreign language

- Halt international support for religious organizations

- Removes meeting form rented closed properties

- Legalizes discrimination on basis of religion and faith convictions

Bulgarian vs Russian New Problematic Laws on Religion

As Bulgaria prepares to assume the Chairmanship of the 55-nation Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), its Law on Religions is a concern, as several provisions are out of step with Bulgaria’s religious freedom commitments as an OSCE participating State. Reports of problems with the new law are already arising. The Sofia City Court, which is mandated to handle all registration applications, has reportedly stalled on the re-registration of some groups, as the new registration scheme includes additional elements not previously required. For instance, since visas are contingent on re-registration, the Missionary Sisters of Charity and the Salesians have reportedly been denied visas. Unfortunately, in the rush to approve the legislation in December 2002, some religious communities were reportedly not consulted during the drafting process, and the government’s promise to have the draft critiqued again by the Council of Europe went unfulfilled. Also, on July 15, 2003, the law was reviewed by the Bulgarian Constitutional Court, in response to a complaint brought by 50 Parliamentary deputies. The Court upheld the legislation, despite six judges ruling against and five in favor. Under Bulgarian law, seven of the court’s twelve judges must rule together for a law to be found unconstitutional. Notwithstanding this decision on the constitutionality of the law, the following report highlights areas in need of further evaluation and legislative refinement in light of Bulgaria’s OSCE commitments on religious freedom. Concerns exist with how the Bulgarian Orthodox Church is favored over the alternative Orthodox synod and other religious groups. In addition, the new registration scheme appears open to manipulation and arbitrary decisions, thereby jeopardizing property holdings and the ability to manifest religious beliefs, as both depend on official registration. The sanctions available under the Law on Religions are also ambiguous yet far-reaching, potentially restricting a variety of religious freedom rights. It is therefore hoped the Government of Bulgaria will demonstrate a good faith effort to ensure the religion law is in conformity with its OSCE commitments. This report outlines a number of suggested changes. The government could also submit the Law on Religions for technical review to the OSCE Panel of Experts on Freedom of Religion or the Council of Europe. Either of these bodies could highlight deficiencies addressable through amendments.

GOVERNMENT RECOGNITION OF A “TRADITIONAL” CHURCH

GOVERNMENT RECOGNITION OF A “TRADITIONAL” CHURCH

Article 11 was crafted to force a resolution to the longstanding church dispute between the Bulgarian Orthodox Church and an alternative Orthodox synod, which split after the fall of communism. Article 11 enumerated detailed characteristics of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, thereby establishing the synod of Patriarch Maxim above the other Orthodox synod and all other religious communities. In short, Article 11(1) attempted to settle the church dispute through legislative fiat by establishing the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as the “traditional religion,” a politically expedient decision which is inconsistent with Bulgaria’s OSCE commitments.

While Article 11(2) automatically registers the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, the other Orthodox synod is faced with going through the complete registration process. Registration is critical, as the law ties property ownership rights to legal personality. However, the process is open to manipulation where the government could deny registration to select religious groups. Considering the animosity between the Orthodox synods over property, this appears to place the unrecognized Orthodox synod at a great disadvantage. Article 11(3) does state: “Paragraph 1 and 2 cannot be the basis to grant privileges or any advantages [to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church] over other denominations by a law or sub-law.” However, while this claims no special benefits accrue, Article 11(2) is contradictory as it automatically gives the Bulgarian Orthodox Church legal personality, an “advantage” no other church or religious group receives through the law. Favoritism of this kind also creates internal conflicts within the religion law, as Article 3(1) prohibits limitations or privileges based on “affiliation or rejection of affiliation to a religion,” and Article 4(4) states “no religiously based discrimination shall be allowed.”

Considering the problematic nature of these provisions, removing Article 11(1) through amendment would allow these two religious Orthodox communities to reconcile their differences independently without government involvement. The appropriate venue for the handling of these types of disputes is the court system, not the Parliament . In addition, amending Article 11(2) either to allow automatic registration of all previously registered churches or omit entirely this provision would lessen the discriminatory effect of the law.

REGISTRATION

It is positive that the law does not require registration, nor does it establish temporal or numerical thresholds for religious communities to meet. Yet, the proper administration of the registration process has increased in importance, since many rights and powers of organizations and their communities appear tied to registration status and other avenues for legal personality have been closed. For example, Article 29(2) provides that nonprofit organizations do not have “the right to accomplish activities which represent practice of religion in public.” As a result, if a group does not obtain official registration as a “religious community,” no other options exist to provide some type of legal personality. The Law on Religions does provide guidelines for the registration process. Article 16 requires that all religious groups wishing to register must do so before the Sofia City Court. This is problematic, as it adds an unnecessary burden for groups existing outside the capital. Improvements to the law should allow the submission of national registration requests in every provincial capital court or other designated government office.

For local branches to form officially, Article 21 requires the organization to first register at the national level and then re-register at the local level through a mayor’s office. While the drafters intended this to be a perfunctory requirement, it is problematic, as it creates yet another unneeded bureaucratic hurdle to overcome. Additionally, the involvement of mayors in the registration of religious groups should be avoided, as in the past registration through mayoral offices were plagued by arbitrary and non-transparent decisions. Revisions should remove registration requirements obligating groups already registered to re-register at the local level. If local re-registration must occur, amendments should permit re-registration at a local court or other designated government office. The Article 19(2) requirement that a “short statement of religious beliefs” be included in an application, which can be reviewed by the Directorate of Religions for an “expert opinion” (Article 18), is highly problematic. This places the government in the subjective position of evaluating the beliefs of a religious community to determine if they “qualify” as a religion. Therefore, the removal of the Article 19(2) requirement is recommended, so that the Directorate of Religion cannot base recommendation for registration eligibility on the religious beliefs of an applicant group.

There are at least two instances in the Law on Religions that demonstrate the critical nature of registration. Article 5(3) appears to allow only registered religious organizations to engage in the public manifestation of religion. “The religious belief is expressed in private when it is accomplished from a specified member of the religious community or in the presence of persons belonging to the community, and in public, when its expression can as well become accessible for people not belonging to the respective religious community.” How the government will apply this article is unclear, as it attempts to distinguish the public versus the private practice of religion. If only registered religious organizations can publicly manifest their beliefs, this is inconsistent with OSCE commitments that protect the right to practice religion with or without legal entity status. It should consequently be made explicit through refining amendments that unregistered religious groups and their members have the right to engage in the public manifestation of their religious beliefs.

Furthermore, it is unclear if individual members of a religious community can own property in their personal capacity for use by the corporate body, as only registered communities can hold property under Article 24(1). The article states: “Religions and their branches, which have acquired status of a legal person, according to the procedures of this law shall have right to their own property.” This reenforces the importance of ensuring the registration process is timely and transparent. Amendments should make explicit that individual members of a religious community may own private property for use by the corporate body.

LIMITATION CLAUSE

Article 7(1) of the religion law provides: “Freedom of religions shall not be directed against national security, public order, people’s health and the morals or the rights and freedoms of persons under the jurisdiction of the republic of Bulgaria or other states.” This language is similar to other limitation clauses, but its structure is problematic, as it enunciates standards not found under Article 17 of the Vienna Concluding Document of the OSCE or Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. For example, the Vienna Concluding Document in Article 17 declared, “The participating States recognize that the exercise of the above-mentioned rights relating to the freedom of religion or belief may be subject only to such limitations as are provided by law and consistent with their obligations under international law and with their international commitments.” The next sentence is also an important qualifier, declaring States “will ensure in their laws and regulations and in their application the full and effective exercise of the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” Article 18(3) of the ICCPR stated: “Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.”

It is well settled that restrictions on manifestations of belief must be consistent with the rule of law and must be necessary in a democratic society— directly related and proportionate to the specific need on which the limitation is predicated. For example, it is not enough to justify burdensome limitations by merely arguing they are key to maintaining public order. Only when limitations further a legitimate government objective and are genuinely “necessary” can negating a religious freedom be justified. To be sure, this test is not easily met. In addition, international custom has not established “national security” as a legitimate reason for limiting religious rights, so amendments to the law should correct Article 7 to reflect the abovementioned international standards.

SANCTIONS

Article 9 of the Law on Religions allows courts to impose sanctions against groups if they determine

that an Article 7 violation has occurred. The six available sanctions available under Article 9 include:

(1) Prohibiting dissemination of certain printed publications;

(2) Prohibiting publishing activity;

(3) Restricting public manifestations;

(4) Depriving registration of educational, health or social enterprises;

(5) Cancelling activities for a period of up to six months;

(6) Nullifying registration of the legal entity of the religion.

The Article 9 restrictions are vague yet extensive in their scope, potentially curtailing a variety of fundamental freedoms. Accordingly, the use of the Article 9 sanctions list must be predicated on a finding of abuse under the Article 7 limitations clause. However, the situations enumerated in Article 7 are for exceptional situations. As these sanctions touch upon fundamental rights, use of Article 9 and the denial of these rights should not occur for mere infractions of administrative regulations. As previously discussed, international commitments make clear that limitations on the manifestation of religion are permissible only in narrowly defined situations.

A distinction must also be made between the actions of individuals and punitive sanctions on the entire religious community. It is individuals, not whole religious groups, who may be involved in criminal activities, so penalties should not punish the entire community for the actions of individuals. However, provision (3) empowers courts to restrict the public manifestation of religious views for an entire religious community, in effect restricting an individual member’s right to practice his or her faith. Provision (6) is also a concern; if a court can remove a religious group’s registration status, it is unclear who would hold their property, potentially exposing their holdings to seizure.

Concerns exist that the Article 9 sanctions list will be employed in situations not meeting international standards, thereby allowing the restriction of the freedom of speech, the freedom to the religious education of children in conformity with the parent’s convictions, and the freedom to profess and practice, alone or in community with others, religion or belief. Therefore, removal through amendment of the Article 9 sanctions list would be positive, as it potentially allows overly burdensome restrictions on basic human rights. Further concerns over potential sanctions exist in other areas of the religion law. Later in Article 37(8), the law also gives the Directorate of Religion the unchecked and potentially arbitrary powers to take complaints from citizens concerning violations of Article 7, and when deemed appropriate, forward the complaints to the public prosecutor. Allowing the Directorate to function in this manner opens the opportunity for the politicization of religious freedom issues, potentially exposing the Directorate to pressures to act arbitrarily against certain minority religious communities. Consequently, legislators are encouraged to eliminate the ability of the Directorate of Religion to forward complaints to the public prosecutor, as this role is better left with law enforcement agencies.

Article 38 has established monetary penalties for “any person carrying out religious activity in the name of a religion without representational authority.” The provision appears crafted to penalize the unrecognized Orthodox synod for using what it considers to be its name, and could easily be misused against religious communities deemed by authorities as unpopular or out of favor.

property.” This reenforces the importance of ensuring the registration process is timely and transparent. Amendments should make explicit that individual members of a religious community may own private property for use by the corporate body.

LIMITATION CLAUSE

Article 7(1) of the religion law provides: “Freedom of religions shall not be directed against national security, public order, people’s health and the morals or the rights and freedoms of persons under the jurisdiction of the republic of Bulgaria or other states.” This language is similar to other limitation clauses, but its structure is problematic, as it enunciates standards not found under Article 17 of the Vienna Concluding Document of the OSCE or Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. For example, the Vienna Concluding Document in Article 17 declared, “The participating States recognize that the exercise of the above-mentioned rights relating to the freedom of religion or belief may be subject only to such limitations as are provided by law and consistent with their obligations under international law and with their international commitments.” The next sentence is also an important qualifier, declaring States “will ensure in their laws and regulations and in their application the full and effective exercise of the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief.” Article 18(3) of the ICCPR stated: “Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.”

It is well settled that restrictions on manifestations of belief must be consistent with the rule of law and must be necessary in a democratic society— directly related and proportionate to the specific need on which the limitation is predicated. For example, it is not enough to justify burdensome limitations by merely arguing they are key to maintaining public order. Only when limitations further a legitimate government objective and are genuinely “necessary” can negating a religious freedom be justified. To be sure, this test is not easily met. In addition, international custom has not established “national security” as a legitimate reason for limiting religious rights, so amendments to the law should correct Article 7 to reflect the abovementioned international standards.

SANCTIONS

Article 9 of the Law on Religions allows courts to impose sanctions against groups if they determine

that an Article 7 violation has occurred. The six available sanctions available under Article 9 include:

(1) Prohibiting dissemination of certain printed publications;

(2) Prohibiting publishing activity;

(3) Restricting public manifestations;

(4) Depriving registration of educational, health or social enterprises;

(5) Cancelling activities for a period of up to six months;

(6) Nullifying registration of the legal entity of the religion.

The Article 9 restrictions are vague yet extensive in their scope, potentially curtailing a variety of fundamental freedoms. Accordingly, the use of the Article 9 sanctions list must be predicated on a finding of abuse under the Article 7 limitations clause. However, the situations enumerated in Article 7 are for exceptional situations. As these sanctions touch upon fundamental rights, use of Article 9 and the denial of these rights should not occur for mere infractions of administrative regulations. As previously discussed, international commitments make clear that limitations on the manifestation of religion are permissible only in narrowly defined situations.

A distinction must also be made between the actions of individuals and punitive sanctions on the entire religious community. It is individuals, not whole religious groups, who may be involved in criminal activities, so penalties should not punish the entire community for the actions of individuals. However, provision (3) empowers courts to restrict the public manifestation of religious views for an entire religious community, in effect restricting an individual member’s right to practice his or her faith. Provision (6) is also a concern; if a court can remove a religious group’s registration status, it is unclear who would hold their property, potentially exposing their holdings to seizure.

Concerns exist that the Article 9 sanctions list will be employed in situations not meeting international standards, thereby allowing the restriction of the freedom of speech, the freedom to the religious education of children in conformity with the parent’s convictions, and the freedom to profess and practice, alone or in community with others, religion or belief. Therefore, removal through amendment of the Article 9 sanctions list would be positive, as it potentially allows overly burdensome restrictions on basic human rights. Further concerns over potential sanctions exist in other areas of the religion law. Later in Article 37(8), the law also gives the Directorate of Religion the unchecked and potentially arbitrary powers to take complaints from citizens concerning violations of Article 7, and when deemed appropriate, forward the complaints to the public prosecutor. Allowing the Directorate to function in this manner opens the opportunity for the politicization of religious freedom issues, potentially exposing the Directorate to pressures to act arbitrarily against certain minority religious communities. Consequently, legislators are encouraged to eliminate the ability of the Directorate of Religion to forward complaints to the public prosecutor, as this role is better left with law enforcement agencies.

Article 38 has established monetary penalties for “any person carrying out religious activity in the name of a religion without representational authority.” The provision appears crafted to penalize the unrecognized Orthodox synod for using what it considers to be its name, and could easily be misused against religious communities deemed by authorities as unpopular or out of favor.

Religion, State and Society 2011

May 20, 2011 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication

Religion, State and Society 2011

Religion, State and Society 2011

Catholic Chaplains to the British Forces in the First World War

Military Chaplains and the Religion of War in Ottonian Germany, 919- 1024

World Religions and Norms of War

“Unity” Established by Force: The Bulgarian Government Raided Freedom of Religion And Democracy

By Viktor Kostov

About a month ago I asked for titles related to freedom of religion and church and state relations in one of the bookstores for legal literature in the Sofia University. The saleswoman, with red-dyed hair and heavy make-up, looked at me as if I were a lower species and literally turned her back to me with the words “I sell only legal literature! All kinds come to this store!” I tried to explain to the lady that the subject I am interested in is actually law of the highest, constitutional order. She answered that she is not even interested in knowing what I have to say and pointed me toward the exit. It may sound unbelievable, but this is a true story.

Also true is the sad realization that ignorance, especially of the arrogant kind and which takes pride in its own self, bears the bitter fruit of a job poorly done. Such are things with church and state relations and freedom of religion and the Law on Religious Confessions in Bulgaria today. The bitter fruit of the hastily put together Religious Law and the disregard for freedom of religion came to a head on July 21, 2004, when the prosecutor’s office raided the so-called “alternative Synod” of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.

“Return of communism,” “unseen aggression,” and “brutal actions” described the situation, by the supporters of the alternative Synod and its leader, in which Orthodox priests where driven away from their temples where they minister. Unfortunately, this aggression was only a matter of time, given the fact that the state, represented by the executive branch and in part by the legislature, took one side in the argument between the two fractions among Orthodox Christians.

Why couldn’t it happen any other way? Because political interests were again radically involved in an internal religious affair. In the new democracy, it turns out, prosecutors are still bound by the law to the extent to which it is interpreted by the ruling political party. The prosecutor’s office is part of the broken-down Bulgarian justice system, in which your chance to predict the development of a legal case, on the basis of the facts and the law, is minimal. The combination of factors, among which is the mood of the young female judge, just out of law school, or of the clerk at the registrar’s desk who patronizes attorneys and calls them “colleagues,” makes the system unpredictable for the regular applicant. Is it possible in this heavy-to-move, hardly working system to conduct a coordinated campaign, in one single night, and in the whole country, unless the prosecutors’ offices have acted by a clear and insistent political order. Inokentii (the alternative Synod patriarch) insists, that the Chief Prosecutor Filchev, has personally gathered and instructed the prosecutors from around the nation how and when to act. The prosecutors’ statements that they just followed the law, engaging the police in the takeover of 250 properties, can sound credible only because of the position of these people. However, if we put two and two together, and look at the picture beyond the dust that the prosecutor’s office is throwing in the public’s eye, it becomes clear that not the law, but a political assignment is what has put the rusty machinery into action.

There are several arguments for this statement:

1. The Bulgarian Law on the Religious Confessions does not enlist special rights for the prosecutor’s office to intervene. In other words—the prosecutor has not read his or her law books or purposefully tries to sway the public—bad in both cases. With this in mind, the statements that the prosecutors, who locked out priests and laypeople from their places of worship, are “just doing what the law says” sounds ridiculous. A reason, for the prosecutor’s office, to intervene in the worship services, interrupt them, drag people out and seal the properties, without giving the slightest concern to the way such actions would effect believers, is in not found in the Religious Law. At the same time, the law upholds guarantees for the protection and the sanctity of the right to freedom of religion. Why didn’t the prosecutor decide to uphold the law in that part, which protects the believer and his beliefs? Why did the prosecutor not think about the damage to be done to the souls of the people, if he/she would seek only for the formal grounds for the execution of the political order? The answer is obvious: the purpose of the prosecutor was to protect himself, and his job, not the law or the citizens. The fulfillment of political assignments by the prosecutor’s office is a bad sign for the return of Soviet-type methodology of state rule.

2. The grounds for action of the prosecutor’s office and the police in Sofia was not the Law on Religious Confessions but a complaint by patriarch Maxim of “intrusion”—the legalese for “someone has settled into another’s property and does not want to leave.” The prosecutors should have had a different approach in this case of “intrusion” alleged by Maxim. This case was not about a domestic dispute, a drunken brawl or the eviction of old renters in favor of the new owner. The case affects the rights and legal interests of people as they relate to the freedom of religion and are protected by the law of highest rank. Ministers and believers in the whole country are affected. The reading of the Law on Religious Confessions, of the constitution of Bulgaria and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ratified by Bulgaria and in effect in Bulgarian law) in this case was mandatory. A careful reading would have made the prosecutor’s office realize the delicate situation it finds itself in –

That it is in danger of violating the constitution, the Convention and even the Law on Religious Confessions, regardless of how bad it is. We all had to listen, instead, to the stubborn assertions that the law was upheld. Unfortunately, it could not have been any other way, because the letter of the law was obviously a good reason not to apply the spirit of the law, which is to do justice based on truth and impartiality.

3. Highly organized effort. The attorney for the alternative Synod, Ivan Gruikin, rightly noted that in its effort against crime, the prosecutors enthusiasm for upholding the law is much less vehement and uncoordinated as opposed to the struggle against the “dangerous” believers and priests (after all, they could say a prayer or conduct a liturgy). A serious effort of the whole state prosecution institution is necessary in order to force priests and worshipers from 250 Orthodox churches and properties from all over the country, only within a few hours, to interrupt their services, expression of faith and fellowship with God. The freedom of conscience and freedom of religion, and the feelings of people in this regard, which are protected not only in the LRC but in the Bulgarian Constitution as well and in the European Convention, were trampled on in a reckless manner.

4. The Directorate “Religious Confessions,” which is with the executive branch of the government, in the face of professor Zhelev, did not intervene to prevent the hasty actions of prosecutors and police. The Directorate has the duty to do that according to LRC (art. 35, para. 7 “observes the upholding of religious rights and freedoms by the responsible state officials” or “observes that officials do not violate the order of religious rights and freedom.” Just to the contrary, Zhelev expressed opinions in favor of the recognized-by-the-state, i.e. the ruling party, synod of patriarch Maxim. His words, quoted in several online news publications were: “Lets hope that the priests (of Inokentii’s synod) will come to their senses and will return into the canon of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.” Such an attitude is an impermissible taking of sides by the state in an argument which the state cannot solve. It only confirms the impression that Zhelev, the prosecutor’s office and the police are working together for one of the parties in this church dispute. The director did not see a problem that worship services are being interrupted, that priests are being dragged to the streets by force, that there are confused, upset and hurt people, who do not really understand what, in the world, is going on. The Directorate “Religious Confessions” called for the return to the true faith, instead. Just like a director should do.

What is the reason for this blatant failure of the post-communist democracy in Bulgaria? The government leaders’ flirtations with the Orthodox Church and that of the Orthodox Church with the government played a bad joke on everyone. Bulgaria has a years old tradition imported first from the Byzantine Empire, then cultivated in a Russian and Soviet fashion, and re-imported from the north. This is the doctrine of “symphony between church and state.” If you ask well-informed Orthodox believers they would object that this is a doctrine that is typical for Eastern Orthodoxy. They would say that the Eastern Orthodox church does not seek recognition from the state. Simultaneously from history and from contemporary events, we see that the Orthodox institution has liked the support of state authority and the reverse, the state authorities have liked the support of the masses secured by the respect shown to the Orthodox church, and this has been a priority in government policy. In this respect, the state needs a united church and the church needs a strong state authority to back it up. At the same time, neither of these is needed in the contemporary free civil society.

The symphony doctrine, however, does not work well in the environment of post-communist democracy aiming at the western European, and to some extent to the American, model of free market and personal freedom. It is impossible for the government to secure the freedom of religious choice if at the same time it is striving to establish a single religious institution as its own political choice. There are two possible models of church-state relations, which are at odds at this very moment in the Bulgarian society. The first model is the one of the Russian-Byzantine practice where state-czar (president)-fatherland-people are one, and anyone, who is not of the Eastern Orthodox confession and does not support the king is a national traitor. This is the model of the historical heritage. The second model allows people to freely believe in God, to associate because of their faith and preach it, while the government guarantees them liberty, as far as they do not commit crimes and do not hurt or kidnap others. This is the model of the contemporary, postmodern civil order of individual freedoms. On the other hand, the Bulgarian model has always strived to the “golden middle”—do unto others so as to always get the benefit yourself. (Something rather different from the Golden Rule of Christ—do unto others as you want them to do unto you.) Therefore, the raid of the state against the Eastern Orthodox church led by Inokentii is an expression of this desire to “have the cake and eat it, too”, of a mechanical blending of Eastern tradition with Western image. This saying does not work in free societies, because in a place where there is freedom of speech and information, narrow-mindedness in a person’s character or in an organization’s philosophy of management cannot pass by unnoticed and unpunished by the public’s opinion. After all, in this case fundamental human rights and freedoms where brutally violated, and the democratic reforms in Bulgaria are being threatened.

From the very beginning, along with many other critics, I maintained that this new Law on Religious Confessions (2003) is a time-bomb, that it was written double-mindedly, with a great dose of opportunism and with a complete lack of understanding of the actual value of this most precious civil liberty of man—to believe in God and to worship Him. Now this time-bomb has started to inflict injuries. The church and state symphony is turning into a chaotic crescendo. If this forceful way, with such disregard for the consequences, was used to treat some of the Eastern Orthodox believers and their leaders, which are a significant part of the religious communist in Bulgaria, what treatment can we expect for the lesser number of Christians from other denominations?

The dispute, as it is put between the two Synods and their supporters, cannot be decided favorably unless one of the rivals loses all. Both groups are fighting for the recognition forcefully put in place by article 10 of the LRC. The text sets the standard that there is only one true Orthodox church in Bulgaria.

A disgruntled and overwhelmed young priest, from Maxim’s group, shown on a news report on TV, gave the solution to the problem—the schismatics had to repent and return into the realm of the true church. And who, actually, is to decide who is a schismatic and who is in the right faith? This dilemma has primarily spiritual dimensions. But because of political appetites and state-inflicted disregard of freedom of conscience and religious liberty, the issue has become a political one: the status of “schismatics” has been granted to the alternative synod by the government and the prime-minister favoring Maxim and his synod.

The solution of the dispute is not in the “repentance”, as a political category, but in repentance as the turning of the heart from selfishness to the what is righteous and true. The question remains: how should people repent if they are not convinced that repentance for them should include submitting themselves to the leadership of a patriarch in whom many see a servant from the former communist regime? At the same time, they have no legal opportunity to register an Eastern Orthodox church of their own—the law states that the Eastern Orthodox church in Bulgaria is only one. Aside from its real estate value, the sealed church properties are also communities of believers, whose souls cannot be emptied by a decree from the prosecutor’s office.

It is sad that this is happening at a time when Bulgaria needs a true resolve as a nation in its trials against war on terror. On the other hand, the conflict between the church and the state is positive since it brings the division and rivalry into the open. It is easy to heal an open wound, even at the price of shame for those who easily resort to force when its not needed. This way of bringing about “unity” is a trademark of terrorists and communists alone. It cannot be applied by the authorities of a democratic nation, as Bulgaria strives to be such. Bulgarian rulers must shake-off their wolf’s appetite to control the faith and the conscience of people and let their disputes hang over their own consciences.

Freedom of Religion Declaration

Declaration of the participants in the “Current Problems of Religious Communities in Bulgaria” Conference held on July 13, 2004 in Sofia

To:

1. President of the Republic of Bulgaria

2. Chairman of the Parliament of the Republic of Bulgaria

3. Prime Minister of the Republic of Bulgaria

4. Chief Prosecutor of the Republic of Bulgaria

We, the participants in the “Current Problems of Religious Communities in Bulgaria” Conference held on July 13, 2004 in Sofia, representing religious communities, non-government and social rights organization and citizens, being apprehensive with the attempts of the state to be involved in the internal dynamics of the religious communities and protesting against the tendencies to use the religious problematic for political purposes without taking under considering the numerous protests and objections against the practice of the accepted against our will Confessional Act, in one accord appeal for the applying of the constitutional principles for separation of church and state and for allowing the Bulgarian believers to reach autonomic solutions for the existing problems in their denominations.

We insist for the prosecution of the acts of encroachment on church buildings and the cases of aggression on the pretext of applying the Confessional Act, as well as for the actions purposing the inflaming of religious animosity.

We consider it to be unpredictable and dangerous for society to enforce totalitarian tendencies in the sphere of human rights after fifteen years of democratic changes in Bulgaria and on the verge of the country’s entrance in the family of free European nations.