Convention on Gender Violence Draws Backlash in Bulgaria

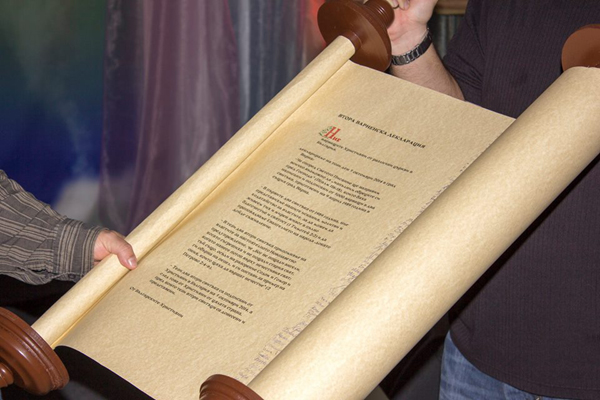

Moves to ratify the so-called Istanbul Convention of the Council of Europe are encountering strong opposition both from parties in the Bulgarian government and the opposition.

Moves to ratify the so-called Istanbul Convention of the Council of Europe are encountering strong opposition both from parties in the Bulgarian government and the opposition.

Members of the Bulgarian government and of the main opposition Socialist Party have joined forces to oppose the government’s decision to pass the so-called Istanbul Convention on gender-based violence to parliament for ratification.

The cabinet approved a national program for prevention of domestic violence on Wednesday, and, as a part of it, advised MPs to ratify the Council of Europe’s convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, which was adopted in Istanbul in 2011. Following the government session, however, the Deputy Prime Minister in charge of social and economic policies, Valeri Simeonov, from the nationalist United Patriots, told the media that eight of the 21 ministers had voted against the document.

“Not only the United Patriots [who have four ministers] but eight ministers voted against,” he said. The names of the ministers who opposed the convention will be revealed on Friday, when the minutes of the cabinet meeting are published. The plan to pass the Convention, which Bulgaria signed in April 2016, for ratification in parliament, drew sharp criticism especially from one of the parties from the United Patriots Coalition, VMRO.

On December 28, the party, led by the Minister of Defence and Deputy Prime Minister, Krasimir Karakachanov, published a statement which claimed that, through the convention, “international lobbies are pushing Bulgaria to legalize the ‘third gender’.

The party declared itself firmly against the document, which it accused of “introducing school programs for studying homosexuality and transvestism and creating opportunities for enforcing same-sex marriages”. Over 30 civil and religious organizations had sent an open letter to Karakachanov, urging him not to allow ratification of the convention. As a result, he said, he had given a negative opinion of what he called the “scandalous text”. What has most upset nationalists is mention of the term “gender” as a social construct as opposed to the biological “sex” in the text of the document, although the explanatory report to the convention notes: “The term ‘gender’ … is not intended as a replacement for the terms ‘women’ and ‘men.’”

Walter Brueggemann: Divine Presence Amid Violence

Review by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

Review by Dony K. Donev, D.Min.

To begin this review quite honestly, I chose the text because of the difficult dilemma it was attempting to resolve, namely violence and the Bible and even more specifically violence and war as ordered by God. The second factor that influenced me was the author. If someone can offer a reasonable apologia on the subject, it is Walter Brueggemann. Of value to my choice was also the perfect timing of the book with the war in the Middle East.

Divine Presence Amid Violence makes clear that aggression in the Bible, and more specifically, aggression that “comes” from God, is not to be against the people, but against the chariots and horses. In the Joshua context, they are the tools used by the evil empire to oppress people and use their labor while holding them in fear. Thus, Yahweh’s command is not to destroy peoples and nations, but to destroy the evil empire that oppresses them through destroying its tools of oppression. This is evident on many occasions in the book of Joshua where cities and ethnos are left untouched by the destruction of Israel’s attack.

One, perhaps shocking, aspect in Brueggemann’s apologia comes in the opening chapter, which deals with meaning and interpretation of the Biblical text before approaching a series of narratives from the book of Joshua dealing with violence in the Old Testament as an order from God. This however, does not give enough reason for the statement in the second chapter that, “It is clear that this text, like every biblical text, has no fixed, closed meaning.”

Brueggemann further asserts that the role of God in the concurring of the Promised Land is merely revelatory. And not just in any context of revelation, but the one of the Land of Promise given to Israel by the God of the Exodus. The command of Yahweh refers to the horses and chariots as tools of an evil empire, the same tools with which Egypt and Pharaoh attempted to stop the Exodus of Israel at the Red Sea. It is from the horses and chariots that the liberated Israel must free the Promised Land, not from people or nations.

A disagreement with Brueggemann for the fundamental Bible scholar here is a must. For it is quite obvious to the reader, that a narrative has a definite and fixed meaning within its own historical context. And while the interpretation of a given passage through various other historical moments or cultural aspects may vary its essence as a piece of history remains intact.

Brueggemann raises an interesting proposal in the conclusion, suggesting that the modern church is often embedded in the culture of chariots and horses, rather than opposing it; thus counter parting a number of modern interpretations of the Kingdom of God and suggesting that with our theology and actions we as people of God are to be liberators from the tools of oppression and not their enforcers.