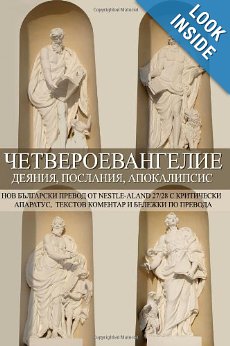

The Four Gospels of the New Bulgarian Translation Published

August 15, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication, Research

We are both happy and humbled to announce the publication of the Tetraevangelion of of the New Bulgarian Translation including:

- Matthew (2011)

- Mark (2010)

- Luke: Gospel and Acts (2013)

- John: Gospel, Epistles and Apocalypse (2007)

This final volume has been almost ten years in the making as it combines all four previously published volumes. It is new literal translation in the Bulgarian vernacular directly from the Nestle Aland Novum Testamentum (27/28 editions).

We thank friends and foes for the internal motivation without which this work would have never been completed.

We are currently working on another similar project, namely the publication of a Study New Testament in Bulgarian, which will be ready for print by the end of this summer.

Luke and Acts Published (New Bulgarian Translation)

We are both happy and humbled to announce the publication of the Luke/Acts volume of the New Testament in Bulgarian. This fourth and final volume of our literal translation was presented to the churches on the day of Pentecost, which this year in Bulgaria was on June 25th. It has taken us almost seven years to complete the translation work as we published: John: Gospel, Epistles and Apocalypse (2007), Mark (2010), Matthew (2011) and finally the Luke: Gospel and Acts (2013). We thank friends and foes for the internal motivation without which this work would have never been completed. We are now working on the publication of a Study New Testament in Bulgarian, which will be ready for print by the end of this summer.

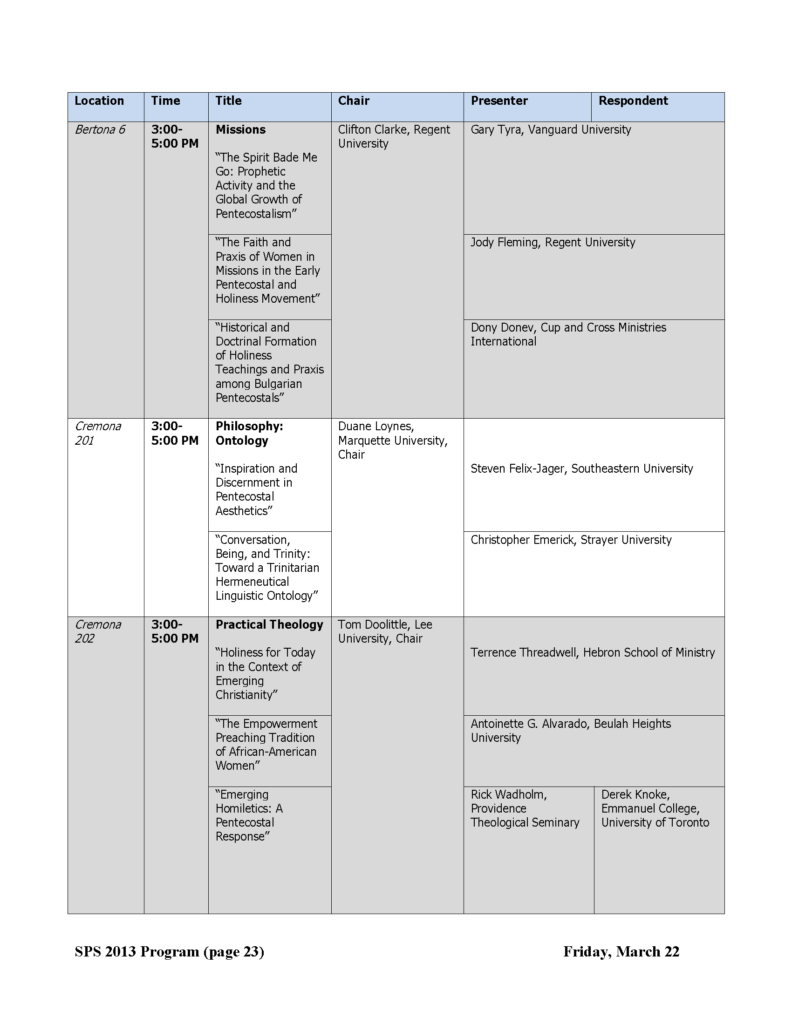

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle Pacific University on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

March 10, 2013 by Cup&Cross

Filed under News, Publication, Research

Presenting at the Society for Pentecostal Studies in Seattle on “Historical and Doctrinal Formation of Holiness Teachings and Praxis among Bulgarian Pentecostals” (Part 1)

21st Century Revival of Study Bibles

June 20, 2012 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication

We are undertaking the task of comparing and reviewing a growing number of Study Bibles appearing on the book market recently in what appear to be a 21st century Revival of Study Bibles. We will be including some classical titles as well, but overall this study will have three parts dealing with three distinct types of Study Bibles namely: (1) Non-Pentecostal, (2) Pentecostal and (3) Prophecy Related. The following titles are among the ones we have chosen to review in the course of the study:

We are undertaking the task of comparing and reviewing a growing number of Study Bibles appearing on the book market recently in what appear to be a 21st century Revival of Study Bibles. We will be including some classical titles as well, but overall this study will have three parts dealing with three distinct types of Study Bibles namely: (1) Non-Pentecostal, (2) Pentecostal and (3) Prophecy Related. The following titles are among the ones we have chosen to review in the course of the study:

I. Non-Pentecostal

- Orthodox Study Bible – in relations to Eastern mysticism and its historical effect on the Pentecostal experience

- Reformation Study Bible – within the scope of formation of evangelical identity among Pentecostals

- Wesley Study Bible – with the purpose of studying the relations between Wesleyan-Holiness tradition and Pentecostal theology

- C.S. Lewis Bible – in the scope of its relation to Pentecostal and Charismatic ethics and religious praxis

- Maxwell Leadership Bible – as per its relations to the leadership paradigms involving and affecting Pentecostal and Charismatic communities

- NetBible and its relations to general formations within Pentecostal Theology

II. Pentecostal

- Spirit Filled Study Bible – written by leading Pentecostal scholars

- Full Life Study Bible – classic Pentecostal and foundation for the youth oriented Fire Bible and the Life In The Spirit Study Bible

- Word Study Bible – including selected teachings from Hagin, Copeland, Sumrall, Savelle, Hayes, Osborn, Wigglesworth, Kuhlman and McPherson

- Kenneth Copeland Study Bible – considered as a fundamentalist Pentecostal teaching

- Jimmy Swaggart’s Expositor’s Study Bible – as an introduction of Pentecostal ethics and praxis

- Dake Study Bible – as a classic example on Pentecostalism and Last Days Prophecy coming together

III. Prophecy Related

- Scofield Study Bible and its dispensational effect on early Pentecostals

- John Hagee Prophecy Bible combining understanding of prophetic themes with doctrines of salvation, covenants, and questions about the Christian faith.

- Jeffrey Prophecy Study Bible regarded as the most comprehensive prophecy study Bible

- Tim LaHaye Prophecy Study Bible combining the knowledge of 48 leading Bible experts of prophecy

- Jack Van Impe Prophecy Bible as a valuable source with a wealth of information on Bible prophecy

- Perry Stone Hebraic/Prophetic Study Bible gleaning from 44,000 hours of Bible Study and produced within 34 years of ministry

F. Sanders (a.k.a. Theologue) has further compiled a comprehensive list of study Bibles, which we truly recommend.

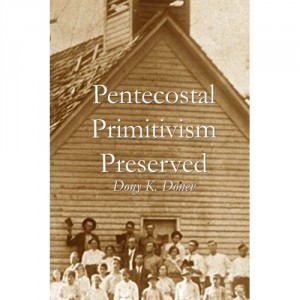

Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved

June 10, 2012 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Books, Featured, News, Publication

Cup & Cross Ministries International is happy to announce the publication of Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved.

Cup & Cross Ministries International is happy to announce the publication of Pentecostal Primitivism Preserved.

Entering the era of the New Millennium, the Christian Church faces a great number of new existential dilemmas. Finding their answers is not only essential, but also formational for the future of the global Christian Community. Failure to do so will transform the church into just another nominal organization separated from the leadership of the Holy Spirit and the power of God.

In attempt to answer the present ecclesial predicaments, this work suggests a way of remembering and returning to the past. Judging from his own Eastern Pentecostal Tradition and personal salvific experience, the author calls the Christian Church to neo-primitivism expressed in the rediscovering and reclaiming of the basic order of the Primitive Church of the first century. Dr.Donev proposes a new understanding of the Pentecostal experience expressed in power, prayer and praxis. Furthermore, reclaiming of the original experience is the answer for the church of the 21st century only if expressed in discipleship after the example of Christ. It is only through such process that the Christian community will be enabled to preserve its own identity and transmit the faith once delivered to the saints to the future generations.

Research and Teaching

May 1, 2012 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, Media, News, Publication, Research, Video, What we do

Empowered by the vision for a continuous revival within the church of the 21st century, we have chosen to make the mission of our work this one statement: We help churches grow.

One of the approaches we have taken to accomplish this ministry goal is Research and Teaching:

- Our historical research through the years has examined the archives of leading Pentecostal movements like the Church of God and Assemblies of God, British and Foreign Bible Society Archives at Cambridge University, Harvard University Archives, Southern Baptist Historical Archives, Graduate Theological Union at Berkeley, as well as various original Bulgarian and Russian sources

- In the area of chaplaincy we have worked with various government agencies, US Army commanders, NATO chaplains and Special Forces representatives in establishing the Bulgarian Chaplaincy Association comprising over 100 active Bulgaria chaplains and founding the first ever Masters’ in Chaplaincy Ministry Program in Europe

Beside personal presence and team building strategies, we implement the media in virtually every approach of ministry. We have published several research monographs as well as film series about our ministry work. Our team holds a weekly TV program called the Bible Hour. (Learn how we help churches build their own and unique web presence)

See also how we help churches grow through:

Religion, State and Society 2011

May 20, 2011 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, News, Publication

Religion, State and Society 2011

Religion, State and Society 2011

Catholic Chaplains to the British Forces in the First World War

Military Chaplains and the Religion of War in Ottonian Germany, 919- 1024

World Religions and Norms of War

The Past, Present and Future of Evangelical Education in Bulgaria

April 5, 2008 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Publication

The missionary strategy of Protestant denominations toward Bulgaria within the 19th century effectively included evangelistic, publishing and educational outreaches. The educational paradigms, which the western missionaries introduced, were soon adopted by the Bulgarian people, quickly realized as progressive and successfully implemented in both religious and secular Bulgarian schools. These trends continued in the next several decades, educating Bulgarian youth and producing the first generation of Bulgarian leaders who took their rightful place in political, economical, social and religious structures in the Bulgarian lands.

Unfortunately, when the Communist Revolution took place in Bulgaria, all religious schools, with the exception of the Eastern Orthodox Seminary in Sofia, were closed down and religious education was outlawed. For the next half century, Bulgarian evangelical ministers were destined to do ministry without any former religious education.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the tension for religious education reached its culmination and a number of religious schools were quickly established across Bulgaria. The instruction methods used ranged from Bible study home groups to Bible colleges all to fulfill the niche for religious education. Two important milestones must be mentioned here, and they are the opening of the Logos Bible Academy in the Danube town of Russe and the starting of a long distance program by ORA International.

Naturally, the general trend of Bulgaria’s post communist governments to control these educational institutions resulted in the registration of a religious institute under the Directorate of Religious Affairs, a government agency formed to register, manage and supervise the activity of religious formation on the territory of Bulgaria. It was in this context that the Bulgarian Evangelical Theological Institute (BETI) was formed and registered in the capital Sofia. It included five departments (often called faculties), representing Bulgarian evangelical denominations with a predominant focus on the Pentecostal wing.

The Theological College in Stara Zagora, often mistakenly called a Theological Seminary, was established in 1998 as one of these departments to represent the Bulgarian Church of God. Because of current developments within the Bulgarian Church of God, the department was started in the city of Stara Zagora, located some four hours east of the capital and became the only of the faculties not located in Sofia. Naturally, its location, staff, affiliation and purpose created a sense of independence, both in its theology and structure.

With the acceptance of the new Act of Confessions in 2002, the Bulgarian government employed a more drastic approach toward all religious institutions not fitting the standard denominational profile. Since BETI was among them, the government initiated the process of the Institute’s accreditation with the Ministry of Education. Five years later, the government is yet to grant the accreditation. It was not until the publication of this article in March, 2008 that the Bulgarian Government moved toward finalizing the long-awaited accreditation of BETI.

Meanwhile the Institute’s management is facing a tri-dimensional dilemma which includes economic, cultural and leadership tensions. Some of them have not been resolved due to the lack of recourses; others have not been resolved due to the lack of essential prerequisites in the long-term educational strategy of the school. The following is a list of the challenges, which must be resolved immediately in order for the Institute to continue to operate under the said government accreditation:

1. The school’s baccalaureate program, structured primarily after 20th century American Bible college model, is practically incompatible with the requirements of the Bulgarian Ministry of Education. The dilemma of changing the program to meet the accreditation requirements or to retain the school’s evangelical identity is yet to be resolved on part of BETI as a whole, as well as its theological departments individually.

2. Three masters programs that were to focus on the subjects of Christian counseling, chaplaincy ministry and missions were secured from the Bulgarian government several years ago. However, because of the lack of students and experts on the said topics, only one of them, the master’s program in counseling, has been partially developed. Today, it remains in its initial phase as a distance-learning program, while the other two programs are virtually untouched.

3. It has taken BETI over a decade to comply with the country’s requirements for higher education. In this process, the school has not facilitated the opportunity for religious master’s programs thus missing its mission to become a higher education authority in religious studies.

4. The resistance toward the evangelical movement and more specifically its presence within the educational process of Bulgarian adolescents has resulted in continuous protests on part of the Bulgarian community. They have been followed by restrictions from the government, which has forced the Institute at the periphery of the educational process. Two waves of attacks against Bulgarian evangelicals in 1990-1993, 2002-2004 and the current trend of the government to establish mandatory religious classes for children ages seven to twelve has contributed to this alienation and has forced the inability of evangelical education to find and establish its place within the Bulgaria community. Much of this has to do with the lack of an adequate placement strategy for graduates upon the completion of the college’s program.

5. Furthermore, scholarships for individual students and sponsorship for the colleges of the Institute has weekend since 9/11 creating an economical dilemma with which the Institute is still struggling. The financial crisis has brought about the rethinking of the economic strategy of the Institute, its dependency on religious support sources and its financial self-sufficiency.

6. Additionally, a number of Roma/Gipsy communities have received substantial educational grants from the European Union upon Bulgaria’s official membership. This has taken a great number of the Roma/Gipsy students within the Institute in a different direction.

7. Immigration has also taken its toll on the Institute’s graduates, as many of them have seized the opportunity to continue their training in religious educational institutions abroad, while other have simple forgone their higher religious education in the struggle for personal survival, both groups never to return and practice in Bulgaria.

8. It is also unfortunate, that most of the professionally trained Bulgarians who have graduated with a higher degree in religious studies from foreign colleges and universities, have been unable to find their place within the structure of the BETI and have been employed in educational institutions, religious centers, ministries and missions which often have to do very little with Bulgaria.

9. The denominational affiliation of each of the departments, has contributed to the dilemma of structural incompatibility with the leadership and vision differences between the denominations that are affiliated with the Institute. The recent crises in several of the member dominations have added to the escalation of the above dilemmas and the incapability for the resolution from a denominational standpoint.

10. Naturally, the well-educated graduates have chosen not to occupy themselves with denominational politics both to avoid confrontation and to express their disagreement. This dynamic has been partially ignored by leadership remaining from the period of the underground church when religious education was virtually nonexistent and lacking a complete realization of the power of education. This unnoticed trend, however, endangers Bulgarian Evangelism creating a lack of continuity within the leadership and preparing the context for the emerging leadership crises.

As an educational institution of the Bulgarian Church of God and a member of the Bulgarian Evangelical Theological Institute, the Theological College in Stara Zagora has experienced all of the above dilemmas and more. Its physical distance from the capital Sofia has jeopardized its accreditation with Bulgaria’s Ministry of Education, the latest guidelines of which have constituted that a school department cannot be more than 25 miles away from its main office. Since Stara Zagora is almost 200 miles away, the Church of God Bible College has been forced to find a suitable alternative. One logical solution may be to move the school or parts of the school to a Sofia location.

However, the Stara Zagora Theological College has had very little if any representation in the capital for its decade of existence. A move to Sofia would propose a number of new problems such as the relocation of teachers and a forced split of focus between two campuses. Another immediate challenge would be the development of a long-term financial strategy to meet a budget, which in the capital would be three-four times the cost of the same operation in the city Stara Zagora. And finally, a successful strategy for establishing a new level of cooperation with the rest of the Institute’s departments, which have operated in the capital Sofia for over a decade is a must, before a successful educational program can be initiated by the Bulgarian Theological College at the new location.

Digital Constantinople Bible Published

January 15, 2008 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Publication

In April of 2007, Cup & Cross Ministries along with our Bulgarian partners released a digitized revision of the first Bible in modern Bulgarian vernacular. The initial translation was first published in Constantinople in 1871 to become the leading text of the Bulgarian Renaissance. Unfortunately, 130 years later certain letters from the alphabet have become distinct and the text is hard to read by the common Bulgarian reader. To provide the text in a readable from, a team of 40 people cooperated in a three–year task which was successfully completed in 2006. The final revision was released by Cup & Cross Ministries in April of 2007 and since then has reached thousands of people. We were successful in signing a contract with the Bible Works software developing team, who will include the digital revised text of the Bulgarian Constantinople Bile in the next edition of the software.

New Bulgarian Bible Translation Released

January 5, 2008 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Publication

It was a great personal joy and satisfaction to see the results of many years of work come to a reality. On Christmas Day, after a long time of prayer, fasting and translating, we were finally able to release a new Bulgarian translation of the Gospel of John prepared directly and literally from NA 27. It was indeed an indescribable feeling to see the first printed copies being distributed to church bookstores, Bible markets and public libraries as our personal and precious gift for Christmas.

It was a great personal joy and satisfaction to see the results of many years of work come to a reality. On Christmas Day, after a long time of prayer, fasting and translating, we were finally able to release a new Bulgarian translation of the Gospel of John prepared directly and literally from NA 27. It was indeed an indescribable feeling to see the first printed copies being distributed to church bookstores, Bible markets and public libraries as our personal and precious gift for Christmas.

Commentators that were able to review the new translation over the holidays are already calling it a “bold step toward the true meaning of the Bible” and “a revolution in Biblical interpretation.” But for us, it is a fulfillment of a long-lasting dream and the fulfillment of a vision which God has put in our hearts many years ago. After over a decade of studies and preparation, the first fruits of this work is finally an undeniable reality – a text of a new translation which can be put in the hands of people hungry for the Word of God. But this is only the first step, only the beginning of something new which God is doing in Bulgaria in 2008.