States Consider Religious Services Essential

DeSantis quietly signs second order overruling all local coronavirus orders, including church bans

Gov. Ron DeSantis quietly signed a second order Wednesday evening that forces local governments to follow the state’s shutdown order to the letter, opening the door to an immediate resumption of activities that cities and counties had banned. But at a news conference Thursday, DeSantis claimed his new order merely “set a floor, and you can’t go below that,” adding that if local governments wanted to close a running trail, for example, they could do so.

Of the 39 states that have implemented stay at home orders, 12 make exceptions for religious gatherings.

A revival held at a church resulted in an outbreak of the virus in Hopkins County, Kentucky, and the governor reminded the public Wednesday that those exercising the exemptions still hold a responsibility to take precautions to the virus. “The ramifications when we don’t follow this, end up being widespread and they hurt people that didn’t make that choice,” said Gov. Andy Beshear. “Let’s make sure that we’re responsible in the choices we make to protect those around us.” Here’s a list of states that still allow some form of religious gatherings during the stay at home orders:

Arizona

Religious services are exempt as an essential activity because worship is protected under the first amendment of the Constitution. However, the exemption specifies that the services are exempt as long as they “provides appropriate physical distancing to the extent feasible.”

Colorado

The state allows houses of worship to stay open as long as they are using an electronic platform or are practicing social distancing. Services from religious leaders are also allowed for individuals in crisis or for end-of-life services.

Delaware

Along with social advocacy, business, professional, labor and political organizations, religious organizations are exempt.

Florida

The state recognizes attending a church, synagogue or house of worship as an essential activity along with caring for loved ones, pets and recreational activities that comply with social guidelines.

Kentucky

Kentucky makes an exemption for life-sustaining business and religious organizations that provide “food, shelter, social services, and other necessities of life” for people disadvantaged or in need because of the pandemic. However, the organizations must social distance as much as possible, including ending in-person retail.

Michigan

Michigan also makes exceptions for operations, religious and secular, that provide necessities for those in need. The state also does not subject places of worship to penalties for breaking orders when they are used for religious worship.

New Mexico

The state does not include congregations in a church, synagogue, mosque or other place of worship in the definition of “mass gatherings” that are barred.

North Carolina

Traveling to and from a place of worship is exempt from the executive order as “leaving the home and travel for essential activities.”

Pennsylvania

Religious institutions are exempt along with lifesaving and sustaining operations, health care, child care for employees of life-sustaining businesses, news media, law enforcement, emergency medical fire fighters and the federal government.

Texas

Religious services, if they cannot be conducted at home or remotely, can be conducted as long as they are consistent with guidelines from the federal government and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

West Virginia

Attending a place of worship is considered an essential activity in the state along with going to the grocery store or gas station, picking up a prescription or necessary medical care, checking on a relative, getting exercise, and working essential jobs.

Wisconsin

Religious facilities, groups and gatherings must have fewer than 10 people in a room and must adhere to social distancing requirements.

The nationwide move to close churches, synagogues and mosques as part of the broader effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus is meeting some new resistance.

In a new “safer-at-home” order banning many activities, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis Wednesday said “attending religious services” is among the “essential” activities that would be permitted. The order came two days after the arrest of a Tampa pastor, Rodney Howard-Browne, who held worship services in defiance of a local ban on large gatherings. That ban is now effectively overruled.

Governors in several other states have also designated houses of worship as providing essential services and thus exempt from shutdown orders. Those provisions have come in the wake of criticism, largely from conservatives, that any order to close churches constitutes a violation of the principle of religious freedom.

Liberty Counsel, a legal advocacy group that represents evangelical Christian interests, agreed to represent Howard-Browne and harshly criticized the move to force churches to close.

“Why is it the church can’t meet when it has a constitutional right to do so and has undertaken extraordinary efforts to protect people, but commercial businesses can meet with no constitutional protections and many do nothing to protect anyone?” the organization said in a press release.

A coalition of Catholic leaders on Wednesday similarly issued an open letter calling on authorities to recognize religious services as essential and pleading for the allowance of “some form of a public mass,” especially at Easter.

Many churches and other houses of worship have been forced to close in response to government bans on public gatherings of more than ten people. It is not yet clear whether the broadening move to include religious institutions as essential will allow churches, synagogues, and mosques to reopen.

In several states that do not explicitly mandate church closures, religious leaders are strongly recommended to suspend services.

An executive order issued Tuesday by Texas Governor Greg Abbott explicitly designated religious worship as essential and thus exempt from a mandate that “every person” in the state “minimize social gatherings” and “in-person contact,” and it overruled the local bans on large gatherings that had forced the closure of many Texas churches.

Legal guidance issued in connection with Abbott’s executive order, however, advised that houses of worship “must, whenever possible,” conduct their activities remotely.

Statement of Dr. Rodney Howard-Browne

Apr 2, 2020

A statement was also made that we ignored repeated warnings. This is patently untrue! On Thursday, Sheriff Chronister spoke to some of our staff by speaker phone. I was also present. After we told Sheriff Chronister that we were enforcing six-foot social distancing, had installed over $100,000 of high-grade hospital air purifiers, and were taking other actions to protect the health of anyone who attended, he said the church could operate on Sunday, and that he had no intention to close the church or arrest anyone. The order then became effective on Friday night at 10:00 p.m. On Saturday, we prepared our building, and our staff and ushers, to take all possible, reasonable precautions. On Sunday, we held our usual meeting with the precautions (listed below) in place. At NO time, before or during the service, did we receive any “warnings” from the Sheriff or any other official.

The March 27 “Safer-at-Home” order contains, in paragraph 3, 42 sub-paragraphs of exceptions, including “religious personnel.” Following this long list of exceptions, in paragraph 5, the order adds another huge exception: “Businesses which are not described in paragraph 3, and are able to maintain the required physical distancing (6 feet) may operate.” (emphasis added). In other words, any business that is not in the long list of specific exceptions, is also exempted if it is able to comply with the six-feet separation between people. In such case, there is no limit on the number of people who can be present.

The church took extra precautions to more than comply with the Executive Order, which included the following:

- Persons who were concerned for their health or had physical symptoms of any kind, were encouraged to stay home;

- Every person who entered the church received hand sanitizer;

- All the staff wore gloves;

- The church enforced the six-foot distance between family groups in the auditorium as well as in the overflow rooms;

- In the farmer’s market and coffee shop in the lobby, the six-foot distance was enforced with the floor specifically marked;

- The church spent over $100,000 on a hospital grade purification system set up throughout the church that provide continuous infectious microbial reduction (CIMR) that is rated to kill microbes, including those in the Coronavirus family.

The church sanctuary has moveable chairs. Chairs were removed from the sanctuary so that the remaining chairs were separated by six feet. Any small group that may have been closer than six feet were family members that came to the church together. This six-foot separation was maintained throughout the church.

The church took every precaution to protect the people who attended. In fact, the kinds of precautions the church undertook cannot be found existing in many commercial business establishments that freely operate in Hillsborough County under this Executive Order.

The Executive Order on its face, and as applied, discriminates against religious services and gatherings, despite the fact that the First Amendment provides express protections to houses of worship and assembly. There is no similar constitutional protection for commercial businesses; yet houses of worship and religious gatherings are singled out for discrimination. The State of Florida’s Executive Order exempts churches, as does the Orange County Executive Order, and many other county orders. Yesterday, Gov. Ron DeSantis issued a new Executive Order that states attending “religious services conducted in churches, synagogues and houses of worship” are “Essential Activities.” Surely, Hillsborough County could follow their lead and not violate the Constitution. There are other means available to achieve the interest that we all share to protect human life.

The word of my arrest has traveled around the world. While I have received vulgar verbal abuse and death threats from people who do not know me and are not familiar with the facts, I have also received many words of support and prayer. Many people are deeply concerned that in America a pastor would be arrested.

As my wife and I prayed about what we should do this weekend, we have decided to close the church for this upcoming Sunday service, for the protection of our people in this antagonistic climate, in large part created by media hype and misrepresentations, which have undoubtedly been exacerbated by Sheriff Chronister’s exaggerated and outright false accounts of the situation. We do not make this decision lightly. This is Palm Sunday. We are entering the time of year that is most important to Christians around the world in which we remember and celebrate the death, burial, and resurrection of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

We did not hold church to defy any order; nor did we hold church to send a political message. We did not hold church for self-promotion or financial motives, as some have wrongly accused. We held church because it is our mission to save souls and help people, and because we in good faith did everything possible to comply with the Executive Order. Indeed, Sheriff Chronister told us last Thursday that we could hold church.

At this point, we believe it is prudent to take a pause by not opening the church doors this Sunday. This will allow an opportunity for people to take a deep breath and calm down. No matter your view on this matter, I encourage you to take a step back and reconsider the options. I believe we can better balance the health and safety of our community without throwing out the Constitution.

At this time, I have not made any decision about Easter Sunday or services thereafter. Adonica and I are praying and seeking the Lord for wisdom. I will say, however, that the church cannot be closed indefinitely. We believe that there are less restrictive means available to balance all the various interests.

My attorneys at Liberty Counsel will vigorously defend me against this unlawful arrest. I have also authorized my attorneys at Liberty Counsel to file a federal challenge to the Hillsborough County Executive Order. As I said earlier, this order violates the First Amendment and is unconstitutional. I have authorized this constitutional challenge for several reasons.

First, I have already been arrested once on trumped-up charges. I am a law-abiding citizen, who respects law enforcement. Like any normal law-abiding person, I would prefer not to be arrested again. A second arrest could escalate to a higher criminal penalty, or even a felony. No one wants to face criminal charges. My attorneys at Liberty Counsel are representing me on the criminal case, which we will move to dismiss.

Second, because of the publicity, the vitriol and death threats that have been directed at us and the church, I feel compelled by these threats to not meet this upcoming Sunday for the protection of our pastors, staff, and congregation. Also, I love my pastoral staff at The River, and they love us and are in agreement with our stance to obey the Word of God and also to stand up for our constitutional rights. If the church holds service this coming Sunday and the Sheriff chooses to arrest me again under this unconstitutional Executive Order, he will probably have to arrest all of our pastors for preaching in my place. Personally, I do not want to put my pastoral staff in a position of having to choose between criminal arrest or carrying out our God-given mission to worship together and lead people to Jesus.

Third, The River Church provides many ministries more than services where we physically gather together to worship. We have various training schools, and we also provide food and clothing to people in need. The Farmer’s Market and the weekly food boxes we provide are greatly needed at this time to help needy and hurting families. These ministries need to continue to operate to help people. We have many inner-city people who do not have the luxury of watching church online at home. We feel obligated to continue to serve them in person and to make sure we continue to provide groceries to them every week. People in our community need help more than ever in this time of crisis, and the church is where many of them turn for spiritual and material help. We need to be able to minister, without unreasonably restrictive measures, to their spiritual and material needs. Church is a body of believers that cannot be substituted online, especially for people who do not have access to the internet, or their internet is too slow to watch video. Our church helps hurting people and those in need, both spiritually and physically. There is no substitute for meeting together to help one another. This can be done while also protecting the health and welfare of those who attend.

No one wants to face arrest for a criminal charge just for exercising a constitutional right. The threat of arrest, and worse, actual arrest, operates as a significant chill to the exercise of constitutional rights. No one should have to choose between the two. Even in times of crisis, the courts are open to protect our constitutional rights. We hope and trust that the authorities in this case would re-consider their actions and choose to uphold the Constitution, for all of our sakes, basing their decisions on actual facts and correctly applying any and all of the law, rather than succumbing to pressure from certain antagonistic media.

May God grant us wisdom and blessings as we approach this sacred time of Palm Sunday and Easter.

CORONAVIRUS STATEMENT by Cup & Cross Ministries International

CORONAVIRUS STATEMENT by Cup & Cross Ministries International

The United Nations have just declared the Coronavirus (COVID-19) a global pandemic. Most European flights are suspended and a number of countries in our area of ministry remain closed. Alternatively, CDC has issued a detail set of resources for faith-based communities and their leaders for preventing COVID-19. As a result, churches are cancelling their Sunday services, conferences and international assemblies.

Having full awareness of the above and convinced by the Bible that “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick,” according to Mark 2:17

WE HEREBY AFIRM that:

- Divine healing [is] provided for all in the Atonement (Psalm 103:3; Isaiah 53:4, 5; Matthew 8:17; James 5:14-16; 1 Peter 2:24 – 42nd A., 1948, pp. 31, 32)

- “The prayer of a righteous person is powerful and effective” (James 5:16)

- And that there is still “power, power, wonder working power in the blood of the Lamb” (L.E. Jones, 1899)

For 30 years now, every public prayer we have held around the Globe has ended with these words:

“WE COMMAND every sickness, every disease, every virus

and ever infection, every tumor and every cancer

to leave the body of the believer in the name of Jesus.”

This prayer includes the Coronavirus (COVID-19) as well and therefore

WE FIRTHER AFIRM:

- Our commitment to REVIVAL especially in the year 2020

- Our long-scheduled Revival Harvest Campaign in celebration of the First Centennial of Pentecostalism in Bulgaria (1920-2020)

- Our readiness to respond to every church, state and national office that contacts us with a request to schedule our ministry in due time.

The Cross of Calvary cancels every coronavirus!

Revival must go on…

Sincerely,

Dr. Dony & Kathryn Donev

Cup & Cross Ministries International

Global Network of Bulgarian Evangelical Churches outside of Bulgaria (2020 Report)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in the European Union (2019)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in the European Union (2019)

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Germany

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Spain

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in England

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in France

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Belgium

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Italy

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Cyprus

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Crete

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in America (2019 Report)

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Chicago (2019 Report)

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Texas (2019 Report)

- Bulgarian Evangelical Churches – West Coast (2019 Report)

- Atlanta (active since 1996)

- Los Angeles (occasional/outreach of the Foursquare Church – Mission Hills, CA)

- Las Vegas (outreach of the Foursquare Church – http://lasvegaschurch.tv)

- San Francisco (occasional/inactive since 2012, Berkeley University/Concord, CA)

Bulgarian Evangelical Churches in Canada (2019 Report)

- Toronto (inactive since 2007)

- Toronto/Slavic (active since 2009)

- Montreal (occasional/inactive since 2012)

CURRENTLY INACTIVE CHURCHES/CONGREGATIONS:

- New York, NY (currently inactive)

- Buffalo, NY (occasional/inactive)

- Jacksonville, FL (occasional/inactive since 2014)

- Ft. Lauderdale / Miami (currently inactive)

- Washington State, Seattle area (currently inactive)

- Minneapolis, MN (occasional/inactive since 2015)

READ MORE:

- First Bulgarian Church in Chicago Opened in 1907

- Gateway Cities for Bulgarian Evangelical Churches

- How to Start a Bulgarian Church in America from A-to-Z

- Unrealized Spiritual Harvest as a Paradigm for Cross-Cultural Ministries among Migrant and Disfranchised Ethnic Groups in America Today

Trew General Merchandise Store

Quaint local General Store on the back roads of Tennessee history added to the National Register of Historic Places in1976 (Building – #76002159). On approach to this nostalgic setting, one could almost envision arriving in yesteryear to this establishment. Folks coming in for sugar and flour. I can imagine that some bartering for eggs and such must have taken place. The clapboard siding gives this establishment the quaintness of a time gone by. This gem of an establishment is tucked away on the back roads of Tennessee in McMinn County and west of Delano, TN

TREW’S STORE

Transcribed by: Mary Sue Mason

Revisions by: Bill Bigham

Trew ‘s Store was established in 1890 by John Wesley Trew near Calhoun, TN, the site of the first county seat of McMinn County Tennessee.

It is properly located as being half way between Highway 11 and 411 on Highway 163 where County Road 783 enters. Dentville was a one time postoffice in the store and the community still retains its name. (To the ole timers, anyway.)

John Wesley Trew’s grandparents, Dr. Thomas Trew and wife Nancy James purchased 463 acres in the Calhoun area in 1836. They came here from Jamestown, Kentucky. They stayed in the area, known as Dentville, and raised their family of ten children.

William, John Wesley’s father, inherited 1/2 of the farm in 1862. He developed the farm into a huge enterprise that produced corn, wheat and oats. He also made sorghum and raised livestock.

John Wesley Trew and wife Margaret Ella Porter were parents of nine children and continued to be very successful with the family enterprise and the store was opened to serve the family’s needs in 1890.

One of the sons of John Wesley Trew, Mortimer began as a clerk in the store in 1925.

In 1935, J.W. Trew turned the store over to his children. It operated as Trew Brothers from 1962-1975.

In 1975 Mortimer Trew and his wife Oneta Crittenden became sole owners of the store and changed the name to M.E. Trew General Merchandise.

The store was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

As an interested citizen living in the area, I made a visit to the store in 1996 and took some photos of the store and Mortimer Trew and his wife Oneta Trew. Mortimer spent his whole life in the store. He died in April of 1996. The store is “not” open for business or touring.

2020

In 2020, we will be celebrating 30 years in ministry. Twenty of them alone were spent in America where we have held some 3,000 services across 25+ different states. In these three decades, I have seen genuine revival with the Glory of God moving in only twice.

The first time was in 1990, right after the fall of the Berlin Wall in Bulgaria, when our youth group of a dozen students grew up to 300 during the spring semester alone. One of those nights, 26 young people literally walked through the door of the small hall we were renting, gave their lives to the Lord and were baptized with the Holy Spirit – all of them on the spot in that one service. I can still remember them all speaking in tongues and none of us knowing what just hit us. As the visible glory of God descended upon us, we were not able to shut down the service till well after midnight. We got written up for breaking curfew, but our names were written in Heaven.

The second time was at the turn of the century when in the summer of 1999 the Lord opened doors to preach over 20 revivals. I started seminary in the fall and travelled back to South Carolina literally every weekend that first semester just to finish all scheduled preaching appointments. Some of the readers of this letter well remember that one or more of those meetings were in your church. And I have been praying for the same move of God since then.

Though we have had similar trends in our ministry in 2014 and then at the start of 2017, it was only this year again that I am seeing the signs of a great revival taking place just like in 1989 and 1999. More and more ministers we contact share the same feel for another great revival and after much prayer, fasting and anticipation I have become convinced that God is on the move in 2019.

For these reasons, we are approaching this season of Revival Harvest Campaign in 2019-2020 with great anticipation. We urge you to pray along with us and seek the will of the Lord – what is it that He wants us to do in this season of upcoming Revival? A move of God of such magnitude and rarity should not be taken lightly!

Church on Mission: 30 Years of Ministry in 14 articles on World Missions

Church on Mission: As we get ready to celebrate 30 years in the ministry, 25 of which solely in Missions, we can truly say that 2019 has been one of the most challenging, but also most productive year in missions for us so far. For this reason, we have attempted to sum it all up in 14 articles on World Missions which are being published as a sequel on our Cup & Cross Ministries website in early 2020 as The Church on Mission. We have contributed in publishing further research in missions in the upcoming 2020 Encyclopedia of Global Pentecostalism.

Social Services Act postponed by 6 months in BULGARIA

Sofia. The Parliament has postponed the entry into force of the Social Services Act by 6 months, Focus News Agency reported. The decision was supported by 149 votes in favor, four MPs voted against and four abstained.

Sofia. The Parliament has postponed the entry into force of the Social Services Act by 6 months, Focus News Agency reported. The decision was supported by 149 votes in favor, four MPs voted against and four abstained.

The Social Services Act was passed in March 2019 and was due to come into force on 1 January 2020. Due to protests against the project, the government reached a consensus to postpone it for 6 months. This was what the United Patriots Group proposed and it was accepted by the plenary.

The MPs rejected а proposal made by Volya party to postpone the law by one year, as well as the proposal made by Ataka party for it to be repealed. The MPs also did not accept the proposals by the MRF party for amendments to the Social Services Act.

Joint Statement by President of the United States Donald J. Trump and Prime Minister Boyko Borissov of Bulgaria

November 30, 2019 by Cup&Cross

Filed under Featured, Missions, News, Publication

We, the President of the United States and the Prime Minister of Bulgaria, reaffirm the strong friendship and alliance between our two countries. As friends and Allies, we dedicate ourselves to deepening our security cooperation and to promoting economic growth and prosperity for our two great nations. Today, we are announcing measures intended to strengthen the strategic partnership between the United States of America and the Republic of Bulgaria.

The principal goal of our relationship is to strengthen the transatlantic community as a community of nations, united by shared sacrifice and a commitment to common defense, democratic values, fair trade, and mutual strategic interests. Thirty years ago, with the end of the Communist dictatorship, Bulgaria freely chose a transatlantic orientation. Fifteen years ago, Bulgaria reaffirmed its transatlantic Western choice when it became a NATO Ally.

The United States commends Bulgaria’s leadership and commitments to burden sharing, exceeding two percent of gross domestic product for defense spending this year. Bulgaria also plans to meet its longer-term NATO defense spending pledge by 2024. Our militaries stand together in the defense of freedom and look to reinforce our defense and deterrence posture across NATO’s eastern flank, including in the Black Sea, which is critical for Euro-Atlantic security. The United States and Bulgaria have derived mutual benefit from combined training and other U.S. operational usage of Novo Selo Training Area and Graf Ignatievo Air Base in Bulgaria, and intend to explore ways of furthering our combined training opportunities in the future. The United States and Bulgaria also intend to continue cooperation on the destruction of excess conventional weapons.

The United States commends Bulgaria’s recent purchase of eight F-16 aircraft and its efforts to modernize its armed forces. Bulgaria thanks the United States for its support in this acquisition. The United States and Bulgaria plan to deepen our defense technology and industry partnership. We commit to pursuing additional defense technology and industry partnerships in areas that are critical to regional defense and deterrence, including by continuing to facilitate access to high-end defense technologies and armaments that the United States deems available. Bulgaria commits to provide due consideration to proposals from U.S. defense companies who wish to compete in the Bulgarian market.

The United States and Bulgaria understand that energy security is national security. We underline our common understanding that the diversification of energy sources is a guarantee of energy security, independence, and competitiveness for our economies. Recognizing Bulgaria’s interest in moving toward more efficient and cleaner sources of energy, we will cooperate on increasing the supply of gas from diverse and reliable sources and diversifying the nuclear energy sector. To this end, the United States intends to send a technical team to Bulgaria to work with Bulgarian counterparts to explore the possibilities for further cooperation in different areas of energy, including nuclear. We share the view of only developing energy projects which have a clear economic basis or commercial need. The United States and Bulgaria also plan to work together to enhance Bulgaria’s energy security by supporting expeditiously the licensing and use of American nuclear fuel for the Kozloduy nuclear power plant, in strict compliance with the safety and diversification requirements and the rules of the European Union.

We welcome Bulgaria’s aspirations to become a regional natural gas hub by completing the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria, taking a stake and booking capacity in Greece’s Alexandroupolis floating storage and regasification unit, liberalizing its domestic gas market, expanding gas storage capacity and access, working with Serbia to build another interconnector, and investing in the reverse flow capacity of the Trans Balkan Pipeline to diversify Eastern Europe’s gas imports in compliance with the rules of the European Union. These steps together will significantly enhance Bulgaria’s energy security, lower energy costs for the Bulgarian consumer, and make Bulgaria an energy leader in the region.

We also share a desire to work together through multilateral fora, especially via the Three Seas Initiative and the Partnership for Transatlantic Energy Cooperation, to promote regional development, including via the expansion of vital energy, transportation, and digital infrastructure. Taking into account that secure Fifth Generation (5G) wireless communications networks will be vital to both future prosperity and national security, the United States and Bulgaria declare the shared desire to strengthen cooperation in this field.

The United States supports Bulgaria’s recent efforts to defend the country’s independence and sovereignty from malign influence. We support the long-term efforts of the institutions and agencies involved in investigating and exposing violations of Bulgarian law by foreign malign actors, and we affirm Bulgaria’s right to chart its own future.

We stress that good governance and the rule of law form the basis of our shared security and prosperity. The United States welcomes Bulgaria’s ongoing efforts regarding economic reforms, best practices, and a regulatory framework in pursuit of compliance with international standards, including those of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Bulgaria underscores its desire to begin the OECD accession process as soon as possible.

The United States encourages Bulgaria to further address corruption that hinders faith in public institutions and economic growth. The United States strongly supports media freedom everywhere, since a free press is essential to democratic nations, and encourages Bulgaria to further protect media freedoms.

The United States and Bulgaria proudly underscore the trade and investment ties that link our two countries and our common interest in shaping an investment climate that offers transparency, predictability, and stability, as well as a level playing field for our respective companies. We commit to the principle of fair treatment of investors, to resolving any investment disputes by good-faith negotiations, and to expanding bilateral trade. We also intend to work together to determine when it would be feasible to enter into a Social Security Totalization Agreement. The United States supports Bulgaria’s aspiration to join the Visa Waiver Program and welcomes Bulgaria’s continued progress toward meeting the statutory requirements for designation as a program partner.

The United States and Bulgaria commit to conducting a regular strategic dialogue between our two nations in 2020 and beyond.

Bulgaria Won’t Be Part of NATO Fleet in Black Sea, Premier Says

Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov rejected a Romanian call for North Atlantic Treaty Organization to set up a permanent Black Sea fleet in response to Russian aggression in eastern Ukraine on grounds it will increase military tension and hurt tourism. Romanian President Klaus Iohannis discussed with Borissov and Bulgarian counterpart Rosen Plevneliev proposing the joint initiative that would include Romania, Ukraine, Turkey and Bulgaria, at a NATO summit in Warsaw in July. Borissov said the move would “turn the Black Sea into a territory of war” and that he “wants to see cruising yachts, and tourists, rather than warships.”

“To send warships as a fleet against the Russian ships exceeds the limit of what I can allow,” Borissov told reporters in Sofia on Thursday. “To deploy destroyers, aircraft carriers near Bourgas or Varna during the tourist season is unacceptable.”

Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea and proxy war in eastern Ukraine near NATO territory led the U.S. to rotate troops into eastern Europe and prompted the alliance to set up a 5,000-man rapid-response force that can mobilize within days. To allay fears in former Soviet-bloc nations that they’re vulnerable to attack, the alliance decided this week to deploy a multinational group of 4,000 troops in Poland and the three Baltic nations, all of which border Russia.

According to a 1936 Montreux Convention, countries which don’t have a Black Sea coastline can’t keep their warships there for more than 21 days. NATO members Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria are all Black Sea basin countries. Russia has its own Black Sea Fleet based in Crimea.

Bulgaria hosts a U.S. base, takes part in joint NATO military drills and has troops in Afghanistan, Borissov said. The government is prepared to send 400 ground troops on rotational training as part of NATO brigade that may be deployed in neighboring Romania, he said. The European Union’s poorest state plans to spend 2.3 billion lev ($1.3 billion) to replace outdated Soviet-era armament with new warships and fighters jets.

Bulgarian resorts, spread along the 350-kilometer (217 mile) Black Sea coastline made the bulk of the 2.9 billion-euro ($3.25 billion) tourism revenue last year, or 11 percent of economic output.

“Russia won’t attack Bulgaria with tanks and missiles,” Borissov said citing historical ties based on the Christian Orthodoxy religion the two countries share. “Their actions on Bulgarian territory are different, mostly economic.”

Bulgaria will ask NATO ships to guard the Bulgarian coast only in the case of “a huge refugee wave crossing the Black Sea, should their route across the Aegean and the Mediterranean be closed,” Borissov said, referring to the migrants seeking refuge in western Europe amid continuing war in Syria.

2019 Bulgarian Elections Continue the Same Political Trajectory for 2020

2019 Bulgarian Elections Continue the Same Political Trajectory for 2020

- Over 1.9 Million People Voted with Ballot, Nearly 160 Thousand – with a Machine

- Newly Elected MEPs to Joint Action on the Mobility I Package

- Names of All 17 New Bulgaria’s MEPs Became Clear Late Last Night

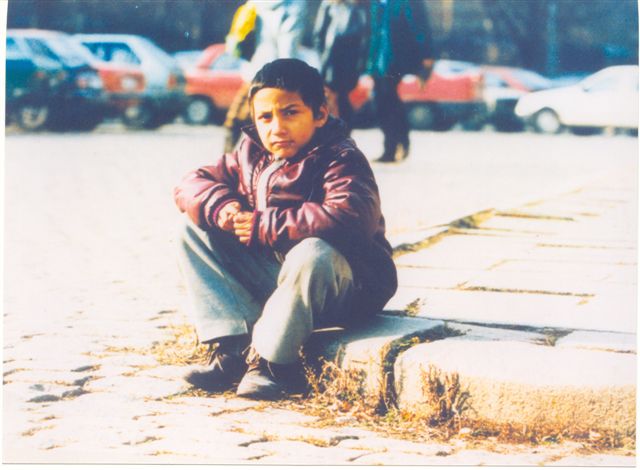

Our preliminary impressions of the political and economical situation in Bulgaria were based on the recent acceptance of the country into NATO and its anticipated admission into the European Union in 2007.Immediately before our arrival, the elections were won by the Socialist party which brought extra tension to the country, although less than 50% of the population participated through their votes.

The Bulgarian Christian Coalition, representing Evangelicals, won only 21,000 votes while struggling to remain politically active. Nationalistic urges among political circles were also common.

Violent public executions among underground cartels have become a normal event in Bulgaria’s everyday reality. The economy has also been dramatically affected as over 90% of the population lives on the verge of poverty. The price of gas grew in the fall and led to the increase of the cost of food, electricity and travel. Various evangelical churches, some of which are pastored and attended by friends of ours, were targeted by the media. Articles against them infiltrated many evangelistic activities among Romani and other minority communities.

These media attacks remind of similar anti-protestant campaigns during 1990-93. Hopefully, this time, the evangelical churches may be prepared to respond adequately.

As we have previously proposed, this puts Bulgaria back on the “Red Light of 30 Years of Communism…” as in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020…

Government Elections in Bulgaria (2005-2019):

2005 Parliamentary Elections

2005 Parliamentary Elections

2006 Presidential Elections

2007 Municipal Elections

2009 Parliamentary Elections

2009 European Parliament elections

2011 Presidential Elections

2011 Local Elections

2013 Early parliamentary elections

2014 Early Parliamentary Elections

2015 Municipal Elections

2016 Presidential election

2017 Parliamentary elections

2019 European Parliament election (23-26 May)

2019 Bulgarian local elections

2019 Municipal Elections

Bulgarian Orthodox Church calls for abortion ban, compulsory religion in schools, no sex education

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church’s governing body, the Holy Synod, has called for a complete rewrite of the government’s National Strategy for the Child 2019-2030, urging a ban on terminations of pregnancy, for religion to be a compulsory subject in schools, no sex education, and opposing the full ban on corporal punishment in schools.

The strategy, which succeeds the 2008/2018 version, was posted for comment on the government’s strategy.bg website in January and closed for comments on February 8. The church posted its comments on the Patriarchate’s website and they were annexed to the strategy.bg website.

The church said a ban on termination of pregnancy would make it possible that “our society and in particular Bulgarian children will receive a new chance for full existence and blessed progress, and our society – an opportunity to overcome the demographic crisis”.

It said that termination could be allowed only if the mother was so severely ill as to make childbirth impossible or if the foetus was not viable “such as anencephaly (a child conceived without a head)”.

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church also called for religion to become a compulsory subject in schools.

“Religious education in kindergartens and schools educates not only the minds but also the hearts of the smallest members of our society, which means that religious activities (in particular: Orthodox Christianity) reveal to children the sacred secret of this, that man is created in the image of God, and that to educate means to develop not only intellectually, but also to be perfected in faith, hope, love, charity and godliness.This is and should be the highest goal of any education, of any education-form, that man should be likened to the image of his Creator,” the church said.

The church said that quality education for all children would not be complete without compulsory religious education, with the option of “choice among several strands, depending on the views and religion of the family and the child”.

It opposed the idea of sex education at schools, insisting that “the younger generations are educated about the value of true love and not about sexuality that is taken out of the context of love”.

The church said that young people should be taught that the best contraceptive is abstinence, rather than “sexual permissiveness when using contraception before and outside marriage”.

The church expressed fear that programmes related to “healthy lifestyles, sexual behaviour and health” of children in pre-school and school will be given to “government officials, non-governmental organizations (often pro-LGBT-oriented NGOs), and educators with dubious beliefs”.

Responding to the concept of “all rights for all children”, the church insisted that the rights of parents be protected too and that parents’ authority is not diminished with “artificial and extreme limitations on the educational methods that can be used in raising children”.

The church also opposed the full ban on corporal punishment of children by stating support for “acceptable verbal or physical means to correct child behaviour”.

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church also called for respecting the attitudes and needs of Bulgarian society and eliminating the foreign practices and policies that are not applicable to them.

“Children’s rights, parents’ rights, and the protection of the traditional family have a direct bearing on national security, state prosperity and eternal salvation in God,” the church said.

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church is the largest religious denomination in Bulgaria, with close to 60 per cent of Bulgarians having declared themselves to be adherents of it, in the most recent census in 2011.

Article 13 (3) of Bulgaria’s constitution says that “Eastern Orthodox Christianity shall be considered the traditional religion in the Republic of Bulgaria”.