Letters from Bulgaria: Overview of Rev. Ivan Voronaev’s Correspondence

The following article comprises the available documents on the life and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev drafted as a chronological outline for a longer paper, which will be presented at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis. The materials were gathered from several archives across the United States among which were three major ones:

The following article comprises the available documents on the life and ministry of Rev. Ivan Voronaev drafted as a chronological outline for a longer paper, which will be presented at the 2010 SPS meeting in Minneapolis. The materials were gathered from several archives across the United States among which were three major ones:

(1) The Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center where Voronaev’s ministerial records and his reports to Pentecostal periodicals are kept;

(2) The Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives, where records of Voronaev’s publication are preserved;

(3) The Graduate Theological Union of Berkeley, which holds in archive the California Baptist records, where much could be found about Vornoaev’s early minister in the United States (California, Oregon and Washington State) as an ordained Baptist minister.

1886: Ivan Ephremovitch Voronaev was born in Russia under the name of Nikita Petrovitch Tcherkesov.

1908: Having married Ekaterina Bahskirova, Tcherkesov received Christ as his personal savior, during a visit to a Baptist church service, while serving in the Tzar’s army. Shortly thereafter, he was court-martialed for his refusal to bеаr arms. In order to escape, he was provided with the passport of a Christian brother from the Tashkent Baptist Church, whose identity he took for the remaining of his life under the name of Ivan Ephremovitch Voronaev.

1910: Together with his family Voronaev crossed the Chinese border and remained for a short time in the city of Carbin, Manchuria, where he preached in the Baptist church and work in the bank of one of the church members by the name of Shubin.

August 25, 1912: The Voronaev family, along with their two children, after receiving visas for the United States through the consulate in the Japanese port city of Kobe, arrived in San Francisco. Voronaev began working with the First Russian Baptist Church in town, which was founded several years earlier on 928 Atkinson Street by S. K. Kunakov. Voronaev also worked as a typesetter, travelled and preached to the Russian communities in Los Angeles and Seattle, where he established a Baptist church and a mission. Meanwhile, he began publishing the “Truth and Love” magazine for the Russian speaking emigrants.

November, 1912: Voronaev is mentioned for a first time in the annual report of the North California Baptist Convention as a newly accepted minister.

February, 1913: A revival began among the Russian Baptists in Los Angeles and they requested the sending of Voronaev to minister among them.

September 18, 1913: The San Francisco Bay Baptist Association held its meeting at the Russian Baptist Church in town. Voronaev was represented as a pastor, who led the benediction. North California Baptist Convention ordained him as pastor in San Francisco. While living in town, Voronaev attended Berkeley Baptist Divinity School for three years, although school archives do not have his student records. Later on, when ministering in Odessa, Voronaev receives Assemblies of God ordination thanks to his seminary preparation and ministry as a Baptist pastor. In a handwritten request to Assemblies of God headquarters, he points out his date of ordination as October 17, 1913, while the ministerial certificate which he receives as evangelist and pastor in Bulgaria is dated March 10, 1920.

1914: S. Gromov assumes the pastoral position at the Russian Baptist Church of San Francisco, after Voronaev had left for unknown reasons. According to Voronaev, this is the time when he first hears about the teaching of Pentecost while ministering in Los Angeles.

November, 1915: Voronaev arrived in Seattle to begin work among the Russian emigrants and renews the publication of the “Truth and Love” periodical.

October 1916-1917: Voronaev was mentioned in the annual reports of the Baptist Convention of West Washington State as Russian missionary in Seattle.

October 1918: Voronaev was mentioned in the annual reports of the Baptist Convention West of Washington State again, but now as a pastor. The Russian group met regularly at the church pastored by Earners Williams who will later serve as Assemblies of God superintendent in the period 1929-1949. It was Williams who introduced Voronaev to the Pentecostal doctrine.

1917: A number of members of the Russian Diaspora in California and of the Russian Baptist community returned to Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution. The Baptist Church of San Francisco went through a period of church split in 1915-1916, noted in the record of the Baptist Association, as follows: “During the past year this church has passed through dark days on account of the interference of a man of the Pentecostal faith …”

November, 1917: Voronaev organized a Baptist church on Henry Street in New York. His family is befriended by their neighbors by the name of Siritz who are Pentecostal Christians.

1918-1919: The New York Baptist Association reports Voronaev as a pastor of the New York Baptist Church organized in 1916. The church has 10 members in 1917 and 18 in 1918. The 1920 report states that the church has remained without a pastor in the middle of 1919.

June, 1919: Voronaev receives the baptism of Pentecost after his daughter began attending Glad Tidings Tabernacle (Hall).

July 1, 1919: Along with some 20 believers, Voronaev left the Baptist denomination and founded the first Russian Pentecostal Assembly of New York, which held meetings at the building of the 6th Street Presbyterian Church.

Fall of 1919: In a cottage prayer meeting at the home of Koltovich, through the wife Ana, a prophecy was given: “Voronaev, Voronaev, go to Russia!” Voronaev ignored the word until several days later he heard them again while praying alone and obeyed the Heavenly call.

December 13, 1919: Voroneav sent the Pentecostal Evangel a letter which was published under the title “Pray for Russia.”

December 19, 1919: Voroneav contacted the Missionary Department of the Assemblies of God with a letter to H. E. Bell to inquire about Pentecostal believers and missionaries in Russia.

January 1, 1920: Upon Assemblies of God recommendation received in response to his last letter, Voronaev contacted J. Roswell Flower with a request for sponsoring a mission trip to Russia. In return, the “Evangelization of Russia” fund was open. In the letter, Voronaev changed the name of his church from “Russian Christian Apostolic Mission of New York” to “First Russian Pentecostal Assembly of New York.”

March 10, 1920: Assemblies of God issued Voronaev a certificate as a “pastor and evangelist in Bulgaria” valid till September 1, 1921.

June 22, 1920: Voronaev notifies the Assemblies of God about his plans to set sail for Russia with his family on July 13, 1920. The Missionary Department marked the letter with the words: “He plans to return to Russia.”

July 13, 1920: The Voronaev, Koltovitch and Zaplishny’s families set sail on the “Madonna” steamboat from New York to Constantinople. Along with them traveled a group of Kavkaz believers among which was the Bulgarian Boris Klibok.

August 10, 1920: After arriving to Constantinople, they had to wait for visas to enter Russia. Voronaev immediately began meeting with the Russian community in town recognizing the lack of Russian Bibles and Pentecostal churches.

August 15, 1920: „ ….with the help of God opened Russian mission here [Constantinople], and God our work blessed;” Voronaev wrote.

August 30, 1920: „…. we had first baptism with water in river. I baptized one lady wife of a Russian office. Glory to Jesus!”

September 2, 1920: Voronaev sent the Assemblies of God a report about his work in Turkey, which is marked by the receiver with “Works among 100,000 Russian refugees in Constantinople.

September 1920: The annual report of the San Francisco Bay Baptist Association recorded the reuniting of the Baptist church split in 1917.

November, 1920: After waiting for three months in Constantinople, Voronaev arrive in the Bulgarian port city of Bourgas along with the Bulgarian Boris Klibok.

March 5, 1921: The Pentecostal Evangel published Voronaev’s report from Bulgaria where he has been holding Russian-Bulgarian revival services in various churches in the cities of Sliven, Yambol, Varna and Sofia. Seven had received the baptism with the Holy Spirit.

April 16, 1921: The Pentecostal Evangel published Voronaev’s second report from Bulgaria about services in Sliven, Bourgas, Plovdiv and the Baptist Church in Stara Zagora where the daughter of the Baptist pastor from Kazanlak received the baptism with the Holy Spirit.

May 14, 1921: Services in the Congregational Church in Plovdiv and baptismal service in the Martiza River.

June 11, 1921: „In Bourgas, Bulgaria the Lord baptized with the Holy Spirit about fourteen souls. We have about twenty candidates for baptism with water, and about thousand Bulgarians and Russian were there and were much interested.”

July, 1921: The Latter Rain Evangel published an article under the title “Pentecost in Bulgaria” in which Voronaev wrote about new Pentecostal believers in seven Bulgarian cities, his relocation in Varna to work with the local Methodist church and his plan to move to Odessa. The Pentecostal Evangel from the same month wrote, “God called Brother J.W. Voronaeff, who had charge of a Russian Pentecostal Assembly in New York City, to Russia.”

August 6, 1921: The Pentecostal Evangel reported Voronaev to be working “among Russian refuges in Varna at the Black Sea.” The same issue records Voronaev’s apparent intent to move to Odessa: “Brother J.E. Voronaeff writes that the Lord could use American missionaries in Bulgaria. At the present time He particularly needs two Americans, a man and his wife. Anyone who feels a burden for carrying the Gospel to the Bulgarian and Russian people can address Brother Voronaeff through this office.”

August 21, 1921: The Voronaev and Koltovitch families received the long-awaited visas for Russia and moved to Odessa.

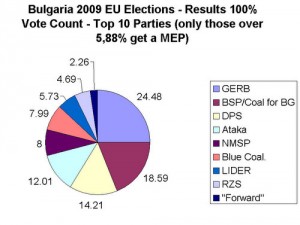

BULGARIA VOTES in the EU Parliament Elections

European Parliament Elections leave Bulgarian Evangelical Churches with no venue of political support.

As an EU member, Bulgaria voted in the EU Parliament Elections on June 6, 2009. After the 100% count, it was announced that GERB (new centrist party led by Sofia’s mayor Boyko Borisov) has won 24.48% of the votes with 627,693 votes. The Socialist Coalition for Bulgaria totaled 476,618 votes or 18.59%, the Turkish Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) received 364,254 votes or 14,21%, the Nationalist Ataka got 307,985 or 12,01%, the National Movement for Stability and Progress (NMSP) of former Tsar and former PM, Simeon Saxe-Coburg, secured 205,145 votes or 8%, and the democratic Blue Coalition got 204,784 or 7.99%. Read more

Research Trip to Nashville

Again we were able to visit the Southern Baptist Historical Archives in Nashville for a time of research and consultation with Dr. Wardin. Since our last meeting with Dr. Wardin in Bulgaria, we have come across several new findings concerning our common research interests, namely the life and ministry of one of the first Pentecostal missionaries in Bulgaria, Rev. Ivan Voronaev.

During our conference we were able to review and compare the developments and make connections with further institutes which have committed to assist in our quest. We have scheduled an appointment with the curator at the Berkeley Seminary to further examine the Northern California Baptist Convention Archives of the early 1900s. We hope to be able to establish a more concrete timeline of Voronaev’s arrival in the United States in 1912 and his consecutive theological training and organizational work as an ordained Baptist minister among the Russian churches of California, Oregon and Washington State.

New Research Trip to Nashville and Urbana

We were able to travel to two locations to obtain valuable materials concerning the Bulgarian Protestant history. The first location was the Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives in Nashville, TN where a good number of Bulgarian Baptist periodical publications from the past 20 years are being preserved. Along with them, we were able to obtain several publications of the Ukrainian Baptist minister Ivan Ephraimovich Voronaeff (Voronaev), who after immigrating to the United States pastored a Baptist congregation in New York until receiving the baptism with the Holy Spirit. After his Pentecostal experience, Voronaeff founded a Russian Assembly in New York which he later left to travel to Turkey, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia to establish Pentecostal churches as an Assemblies of God missionary. Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives in Nashville has preserved a number of issues from the Pentecostal publication “Evangelist,” which Voronaeff began publishing in the Ukraine in the late 1920s.

Also in Nashville, we were privileged to meet with Dr. Albert Wardin, a renowned Baptist historian who has written several pieces on Bulgarian Baptists after his first visit to Communist Bulgaria in the 1960s. We are expecting Dr. Wardin to visit us again in Bulgaria very soon in attempt to begin a round table discussion dealing with the history of Baptist presence and missionary endeavors on the Balkan Peninsula.

We departed from Nashville on our way to Urbana, IL to obtain a long-awaited copy of the Albert H. Lybyer Papers. Dr. Lybyer taught at Robert’s College in Constantinople in the beginning of the 20th century before serving as a member of the Board of Directors of the American College in Simeonovo (a suburb of the capital Sofia). His personal papers at archives of the University of Illinois in Urbana have preserved his correspondence with board members, college officials and representatives of the American Board, which are an invaluable reference to Bulgarian Protestant history. His correspondence as a board member contains unprecedented information of the history of the American College in Simeonovo, and more specifically its merge with the Samokov Missionary School. Dr. Lybyer’s papers contain his personal journals recorded during his early trips across the Balkan Peninsula, which presents the missionary context in early 20th century Bulgaria.

The Case of a NATO Chaplaincy Model within the Bulgarian Army

In April 2004, Bulgaria was officially accepted into the global structure of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The event followed a long series of historic developments that were accomplished despite the existence of highly antagonistic forces that opposed the very idea of Bulgaria’s membership in any Western alliance. Among these were internal and external political, economical and social factors that historically have forced the country to remain under the influence of the forces opposing the West.

Territorially, this tendency could be traced to the dramatic split of the Roman Empire even before the establishment of the first Bulgarian Kingdom on the Balkan Peninsula in 681AD. The consecutive military, cultural and economical influence of Byzantium over the Bulgarian nation claimed the newly established country to the side of the East from its birth. This propensity was sustained through the two Bulgarian Kingdoms (established respectfully in 681AD and 1188AD). It was renewed with even greater strength when the Ottoman Empire overtook the weakened country of Bulgaria in 1139AD and for the next five centuries, the Orient claimed control of European Bulgaria.

In 1878, Bulgaria was liberated from the Ottoman Yoke by Russia, but only to remain under its political and economical umbrella for the next 111 years until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This event reaffirmed Bulgaria’s belongingness to the East as the country joined the Central Powers throughout World War I and deliberately remained with the Axis Powers in World War II. Read more

Research Trip to Urbana, IL

Our third trip to the University of Illinois’s library to discover books and materials on the subject of Bulgarian Protestantism was successful again. Among the findings was a very important book about the famous Pastor’s Trial in Bulgaria. Its story is indeed worth sharing.

In 1949, five years after communism took over in Bulgaria, fifteen evangelical pastors were tried and sentenced to years of imprisonment for allegedly serving as spies for the United States, England and France. This was the first of several waves arranged by the communist government to behead the evangelical movement from its true leaders while implanting secret agents as pastors and ministers within the church. In fact, the Pastors’ Trial was just a small part of a larger political scheme through which the Regime attempted to remove ideological leaders of various Bulgarian professional groups like political leaders, chief of military departments, lawyers, doctors, scholars and such. Unfortunately, following Stalin’s directives, the Communist party of Bulgaria was very successful in executing or imprisoning most prominent leaders in Bulgaria, thus dooming the country to an era of political, economical and social ignorism, which ensured the implementation of their proletarian agenda. As preachers of freedom and puritan values, evangelical pastors naturally opposed the drastic move of the Regime toward dictatorial totalitarianism.

While researching the subject at the University of Illinois, it became apparent that immediately after the trial of 1949, the Bulgarian Communist government ordered the publication of a book which was intended to inform the Western world of the “crimes” of the evangelical pastors. The book was written in satisfactory English, perhaps with the help of a native English speaker, printed in the capital of Bulgaria, Sofia and then distributed around the world. To much of our surprise, the publication contained an English translation of the “confessions” which were extracted from the pastors during the trial and presented as evidence against them.

Later publications contain the memoirs of several of the pastors, as they describe the horrible ways of torture, starvation and depravity of sleep, used to obtain the confessions. Unfortunately, since many of them spent over a decade in various prisons without any means of communicating with the outside world and recording facts and events, the contents of the confessions were impossible to reproduce in their memoirs.

This publication, however, gives a full account of the texts as recorded by agents of the Communist militia. This is the first time that we have become aware of the existence of such publication, as it has been virtually unspoken of by both Bulgarian and foreign studies on the topic. In the future, we will be comparing the English translations with the partial publications of other “confessions” in various Bulgarian periodicals of that time in order to discover variants and modifications between the text intended for the Bulgarian public and the text translated and published for the Western reader.

Orthodox and Wesleyan Scriptural Understanding and Practice

Dony K. Donev, D. Min.

“I sit down alone: only God is here; in His presence

I open and read this book to find the way to heaven”

– John Wesley

Our search for the theological and practical connection between Pentecostalism and Eastern Orthodoxy continues with yet another publication by St. Vladimir’s Press titled, Orthodox and Wesleyan Scriptural Understanding and Practice. The book represents an ongoing dialogue between the Orthodox and Wesleyan confessions and it emphasizes how theologians from both sides are attempting to discover commonalities in theology and praxis. To come together, not so much as theologians and thinkers, but as practical doers motivated by the proper interpretation of Scripture. As observed from the title, as well as through the text, these similarities are not necessarily in theological convictions, but in the proceeding Biblical approach toward interpretation of Scripture.

Orthodox and Wesleyan Scriptural Understanding and Practice is a compilation of essays from the Second Consultation on Orthodox and Wesleyan Spirituality under the editorship in 2000 of S.T. Kimbrough, Jr., who contributed the chapter on Chares Wesley’s’ Lyrical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures. I must issue the caution that the book is not an easy read, at least not for the reader who intends to understand it. But it is by no means a book to be easily passed by Pentecostal scholars searching for the Biblical roots of Pentecostalism within the Eastern Orthodoxy.

The book begins with an interesting observation of the exegesis of the Cappadocian Fathers by John A. McGuckin, and continues with an article on the spiritual cognition of my personal favorite, Simeon the New Theologian by Theodore Stylianopoulos. Although the discussion on Gregory the Theologian, Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa was thoughtful and presented in an interesting manner, the essay on St. Simeon struck me as well structured, but a bit shallow.

An interesting approach was taken in Tamara Grdzelidze’s essay where she presented an orthodox perspective of the Wesleyan position on authority of scriptural interpretation. The essay had a very strong exposition in regard to the Wesleyan understanding of the importance of Scripture in Christian living. However, the latter part, which dealt with the influence of tradition, was not investigated to its full capacity, which left the text (perhaps on purpose) open to multiple interpretations. Nevertheless, this issue was resolved later in the book by Ted Campbell that dealt with the subject from the Wesleyan perspective.

A central theme throughout the book was the comparison of prayers and song lyrics from both camps. Although I am no musical expert, I must agree with the authors, that theology within music has played an important role in both Orthodox and Wesleyan traditions, as it continues to do so in the everyday spiritual experience of the Pentecostal believer. This rather practical approach seemed to be the heart of the discussion where both sides could agree.Finally, the role of the Holy Spirit is viewed as central for the reading, understanding and practicing of Scripture in both the Orthodox and Wesleyan traditions. For the Pentecostal reader, it may be easy to accept this presumption as similar to the Pentecostal experience, yet the book describes it in terms which will be somewhat foreign to many Pentecostals. Although the said similarities between the interpretations of Scripture may be self explanatory for the western Pentecostal reader, they may be easily disregarded as unimportant by people who practice theology and ministry in an Eastern European context due to the ever-present tension between the Orthodox and Protestant denominations. But even if the Pentecostal scholar gathers nothing else from this book, he/she must remember this one thing: The time has come for a formal Orthodox-Pentecostal dialogue, like the one which the World Council of Churches has been trying to put together since 1991.

21 Century Bulgarian Evangelicals

By Kathryn Donev, M.S.Bulgarian evangelicals remain in almost complete agreement on issues such as the person and work of Jesus Christ in the salvific mission of God and the importance of the Holy Spirit in the mission of the church. These are strong Biblical points that should be used to correct the recognized error of past church splits. Because these also serve as the cornerstone of Pentecostal doctrine and practice, a movement toward unity within the Bulgarian Protestant movement should be initiated by Bulgarian Pentecostals. However, before such initiation can be realized, Pentecostals must reach a balance between their numerical advantage and their social action. Bulgarian evangelicals are together on many social issues. These commonalities should be used to build unity and construct strategies for the future development of the movement.

From an environment of uncertainty and hopelessness, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer turns to the continuity of faith in the Almighty Redeemer. Pentecostalism as practical Christianity gives a sense of internal motivation to the discouraged. In a society that is limited in conduciveness for progression of thought or self actualization, one finds refuge in the promises of Christianity. It becomes a certainty which can be relied upon. Historically, having undergone severe persecution, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer is one whom possesses great devotion to his or her belief. Having to defend the faith fosters a deep sense of appreciation and in an impoverished country, faith becomes all some have. Christ becomes the only one to whom to turn for provision. In the midst of this complete dependence is where miracles occur. Furthermore, it is in the midst of miracles where the skepticism which is prominent in postcommunist Bulgaria is broken. When those who believe are healed from cancer and even raised from the dead, there is no room for disbelief or low self-esteem.Surrounded with insecurity and uncertainty, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer finds great hope and comfort in the fact that God holds the future in His hands. Christianity is a reality that is certain. While having lived in a culture of oppression and persecution, the Bulgarian Evangelical believer now can trade a downtrodden spirit for one of triumph. The once atmosphere of turmoil is being transformed to one of liberation in the Spirit where chains of slavery are traded for a crown of joyous freedom.

iving in the 21st century in a context of postcommunist and postmodern transformations, Bulgarian evangelical believers must remain true to their historical heritage and preserve their identity in order to keep their faith alive. This unique testimony must be pasted on to future Bulgarian generations by telling the story of the true Pentecostal experience.

Practice and Politics

By Kathryn Donev, M.S.

Most of Bulgarian protestant believers pray (88%) and read the Bible (77%) on a daily basis. Over half (59%) have read the whole Bible at least once and own more than 50 Christian books. Only a third fast more than once a week. The majority recognize the use of alcohol as sin (60%) and only a tenth have ever tried drugs. Thus, Bulgarian evangelicals are more traditional than contemporary in conviction, more practical than theoretical in teaching and more conservative than liberal in practice.

A certain level of negativism regarding politics and political order is inherited among Bulgarian evangelicals from the times of the Communist Regime. This feeling may be represented in the broader Bulgarian context by the fact that 80% agree that the average Bulgarian has lost faith in general. The church is not a political organization for most Bulgarian evangelicals (62%) and 57% claim it is not Biblical for a Christian to be a politician. Perhaps, this is the reason why over half (53%) would not vote for the Bulgarian Christian Coalition as a political force formed to represent evangelicals in Bulgaria. The same attitude applies to the broader political scene, as almost half (42%) of Bulgarian evangelicals did not intend to vote in the 2006 Presidential Elections and 48% actually did not vote. However, a much larger number (79%) intend to vote for an evangelical candidate for president. Perhaps, this is the number which the Bulgarian Evangelical Coalition should take into consideration when modeling their future political platform to gain much needed support within the evangelical churches.

Such a political alternative has been much awaited as the majority of evangelicals (64%) feel there is no religious freedom in Bulgaria. As in many other areas of the Bulgarian reality, true religious tolerance is replaced by the monopoly of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Evangelicals have not been heard in the legalization of a number of issues like chaplaincy, capital punishment, euthanasia, abortion, organ donation and so forth. Perhaps, this is the reason why attempts to constitutionalize Eastern Orthodox monopoly are generally met with strong resistant from evangelical circles. This is why a large majority (80%) demand a new Bulgarian law of religion.

Bulgarian Evangelical Theology

By Kathryn Donev, M.S.

A great majority (97%) of Bulgarian protestant believers accept the evangelical doctrine of receiving Christ as Savior as mandatory for personal salvation. In this context, over three-fourths affirm the existence of free will (86%), as part of one’s personal choice to be saved (75%) and respectively to loose one’s salvation (76%).

Water baptism is viewed as unnecessary for salvation (85%), yet people baptized in water as children, as is customary in Eastern Orthodox tradition, need to be baptized again after conversion (70%). Almost two out of three (64%) claim that infant baptism is not a Biblical teaching.

Much more attention is paid to the role of the Holy Spirit in the life and praxis of the church. Although the majority (72%) claims that baptism with the Holy Spirit is not necessary for salvation, a close number (76%) attend a church where speaking in tongues is practiced and 63% claim to have received the baptism of the Holy Spirit. A striking majority (90%), which apparently includes people not baptized in the Holy Spirit, affirm that the gifts of the Spirit are still operational. Additionally, two out of three Bulgarian Evangelicals are pretribulational in eschatology, which however is not always based on dispositional interpretation.

From a theological standpoint, Bulgarian protestant believers are fundamentally Biblical and conservatively-evangelical in doctrine, especially in their sotierology, and more Biblical than sacramental in practice. The majority of Bulgarian protestant believers are Pentecostal/Charismatic in experience, leaning toward a personal experience of the faith and supporting a more experiential personal salvific conversion, rather than traditionally inherited national religious confession. The genuine experience of God produces in a desire to practice the Biblical truths and be led by the Spirit, while expecting a soon and sudden return of the Lord.