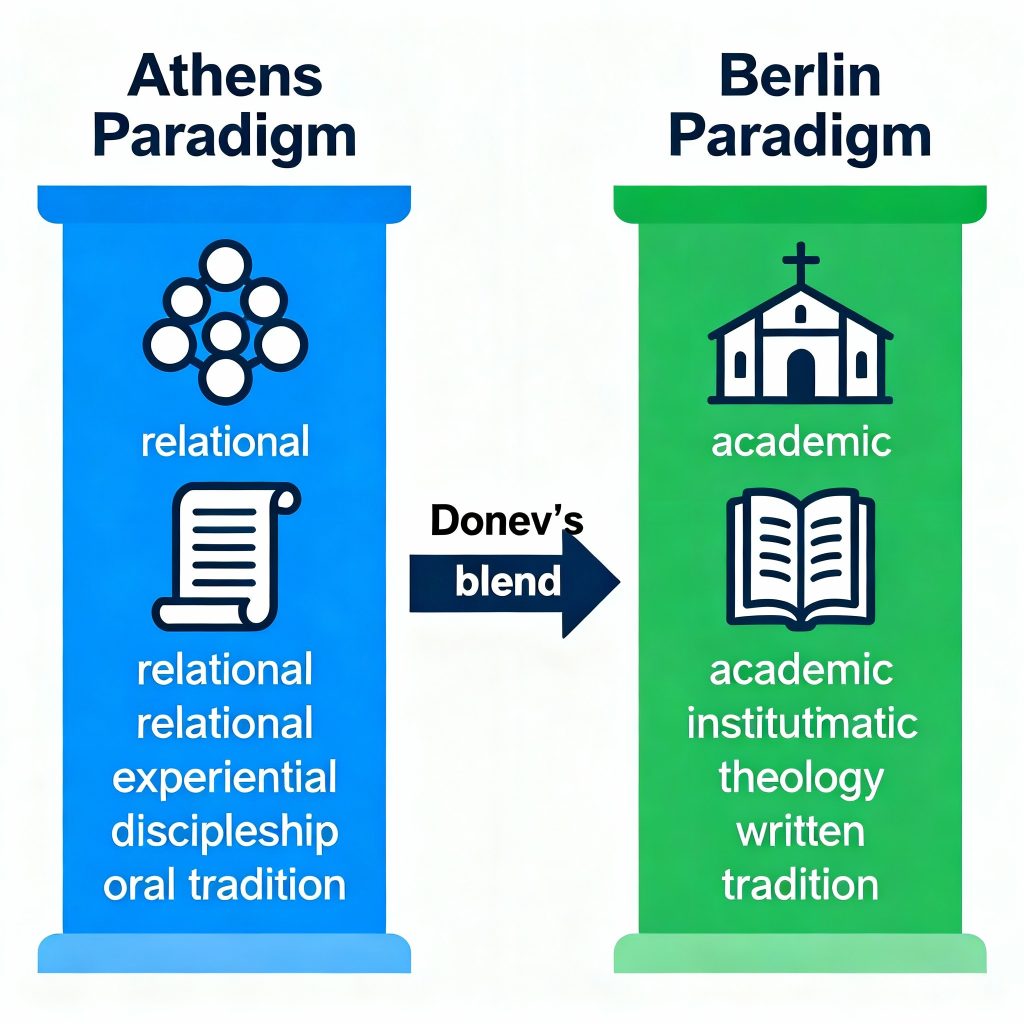

Frameworks and Key Terms by Dr. Dony Donev: Athens vs Berlin Paradigm Shift

Core Theological Frameworks

U.S.H.E.R. Model of Communion

A theological framework coined during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Donev’s Intro to Digital Discipleship course at Lee University. It defines what follows Communion in Christian catechism, identifying five foundational dynamics for disciple growth: Unity, Sanctification, Hope, Ecclesial communion, and Redemptive mission.

Freedom Theology (Theology of Freedom)

Developed through Donev’s research on postcommunist Eastern Europe and the Bulgarian Protestant experience, this framework explores biblical concepts of freedom, liberation from both sin and socio-political oppression, and the church’s transformative mission as a liberator in history. It often appears in his writings as “Feast of Freedom,” drawing connections between national liberation and spiritual renewal.

Primitive Church Restorationist Model

Based in his historical research, Donev advocates for returning to the original practices and structure of the Early (Primitive) Church. This model emphasizes rediscovering authentic spiritual identity, intergenerational faith transmission, and revivalist community rooted in biblical precedent.

These frameworks have had meaningful impact on global Pentecostal studies, digital discipleship, and liberation theology, addressing contemporary challenges in theology, worship, and ecclesial practice.

Effect on Donev’s Models

-

U.S.H.E.R. Model: By anchoring his post-Communion framework in the “Athens” paradigm, Donev prioritizes unity, lived discipleship, and communal mission over purely doctrinal or institutional forms. This perspective shapes the model to valorize shared spiritual experience and relational growth, not just catechetical instruction.

-

Freedom Theology: “Athens” influences Donev’s liberation emphasis by grounding freedom in communal lived reality, while “Berlin” marks the shift toward codifying and structurally analyzing liberation.

-

Primitive Church Restoration: Donev navigates between Athens’ restorationist, dialogical church identity and Berlin’s historical-critical, analytical methodology, advocating an integration that revitalizes spiritual community while acknowledging scholarly insights.

In sum, Donev’s “Athens vs Berlin” usage intentionally blends experiential, relational Christian practice (“Athens”) with disciplined, systematic theology (“Berlin”). This dynamic underlies his frameworks, ensuring they are both deeply incarnational and critically constructive.