Let’s jump in!

The Last Chief John Ross Indian Detachment: Fort Marr , Ocoee River, Hildebrand Landing Hildebrand Landing, Old Federal, Old Fort and King’s Highway

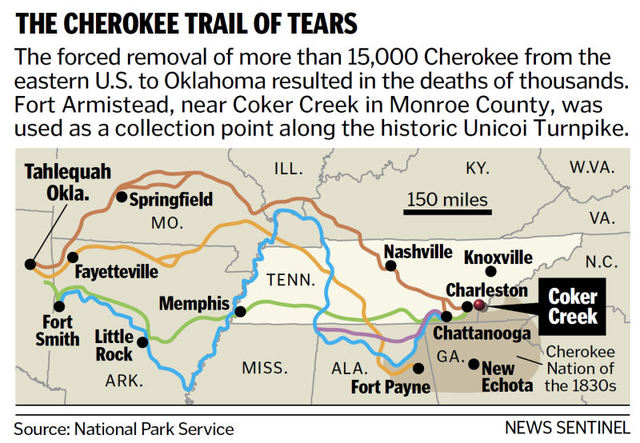

Among the Ross-allied detachments, nine would depart from the agency area traveling overland across Tennessee, Kentucky, southern Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas to the Indian Territory. One detachment, composed mainly of elderly and sick Cherokees, would travel by river departing from the Agency on the Hiwassee River. Two more would begin from camps near Ross’s Landing and travel northward to join the main route. The last would leave from its camps south of Fort Payne, Alabama and cross Tennessee into Kentucky and on to the west. Figure 3 shows the general routes of removal (King 1999:Section 1, 21-25; Foreman 1956:301-312). [The details of the routes are given in the next section of this report.] The last detachment, led by Peter Hildebrand, departed on November 7, 1838, and John Ross and his family left with this group. The detachments were plagued with high tolls and whites bent on selling whiskey to the Cherokees and swindling them out of their money. There were large numbers of sick among the detachments and constant wagon breakdowns. Morale was low and many Cherokees deserted. The Cherokees had organized their own light horse police force to keep order, but there were not enough of them to deal with the many problems that arose daily. The wagon master for the Elijah Hicks (Second) Detachment died at Woodbury, Tennessee on October 21. Elderly Chief White Path also died near Hopkinsville, Kentucky. Rain made travel on the road difficult, and the thousands of Cherokees traveling the roads caused severe damage and erosion, making travel more difficult for those behind. Severe winter weather came early, and Winfield Scott, traveling northward on military business, commented that he found much snow on Walden’s Ridge and the Cumberland Mountain as early as November 17. Icy conditions on the Mississippi River trapped seven detachments for nearly a month, unable to cross. At Paducah Kentucky, John Ross, traveling with Hildebrand’s (Eleventh) Detachment, met the John Drew Detachment traveling by river. Ross boarded the steamboat Victoria with his family because his wife Quatie was severely ill. Quatie later died on the journey (Moulton 1978:99-1 00) . The Cherokees finally arrived in the new land after a long and arduous journey. Many died as a result of the process of roundup from their homes, their long internment in the stockades during the hot summer, and their difficult journey through severe weather. The most commonly accepted estimate of the number of Cherokee deaths is approximately 4,000. This number may also include those who died during the first year in the west as a result of disease and starvation (Thornton 1991 :83-84). The end of the journey was not the end of the strife that had divided the Cherokees, for the factionalism that had developed before the removal still remained in the new nation. Additionally, the subsistence that was promised to the Cherokees to help them through the initial period in the new land was inadequate and often of inferior quality. John Ross appealed to both Monfort Stokes, the Cherokee Agent in the new territory, and General Matthew Arbuckle, commander of Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Territory, but neither was able to render assistance. Ross was forced to use funds allocated by General Scott so that the Cherokees could buy food and essential supplies (Carter 1976:268). The Western Cherokees welcomed the Easterners to their new home but informed them that they were expected to conform to the established government of the Western Cherokee Nation. Chief John Ross and his assistant George Lowrey insisted that the now re-united bands of Cherokees call a council to form a new government. At a council held at Takatokah in June 1839, Cherokee leaders decided to meet in the following month to form a new government, uniting the Eastern and Western Cherokees (Carter 1976:268-269). On June 22, 1839 a group of Cherokees, bent on revenge against those who supported the Treaty of New Echota, assassinated John Ridge, Major Ridge, and Elias Boudinot. General Arbuckle, believing that Ross knew of the killings beforehand and might even be harboring the murderers, asked Ross to come to Fort Gibson to discuss the incident. Ross refused Arbuckle’s request and hundreds of supporters surrounded Ross’s home for their Chief’s protection (Carter 1976:270- 272). Eventually a new government was formed with its capital at Talequah. John Ross was elected Principal Chief with David Vann, a western Cherokee, as assistant chief. President Martin Van Buren’s administration refused to recognize the Ross government, and former President Andrew Jackson encouraged John Bell and Stand Watie, pro-removal Cherokees, to “lay the tyrant low.” Ross held on to power through trying times during which the Cherokee nation was on the brink of a civil war. Finally in 1846, the U. S. government met with the Western Cherokees, the pro-treaty Eastern Cherokees, and the Ross supporters to sign a treaty of unity.

Under this treaty, the United States finally paid the $5 million owed to the Cherokees under the Treaty of New Echota. There was now relative peace in the Cherokee Nation, and that peace would last until the outbreak of the American Civil War (Carter 1976:272-275).

- https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/environment/archaeology/documents/reportofinvestigations/arch_roi15_trail_of_tears_2001.pdf

- Polk County Christmas Parade Route Shadows the Footsteps of the Historic Cherokee Removal

- The Old Federal Road and the Cherokee Trail of Tears

- Historical Significance of the Tennessee/Georgia Old Federal Road in the Trail of Tears and its Connection to the Church of God

- Ocoee Church of God Celebrates 40 Years

Historical Significance of the Tennessee/Georgia Old Federal Road in the Trail of Tears and its Connection to the Church of God

Historical Significance of the Tennessee/Georgia Old Federal Road in the Trail of Tears and its Connection to the Church of God

Historical Significance of the Tennessee/Georgia Old Federal Road in the Trail of Tears and its Connection to the Church of God

New Echota, Georgia was the capital of the Cherokee Nation from 1825 to 1838. This is the location where the Treaty of New Echota or the Treaty of 1835 was signed on December 29, 1835 by U.S. government officials and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction called “The Treaty Party” or “Ridge Party”. This treaty was not approved by the Cherokee National Council nor signed by Principal Chief John Ross. Regardless, it established terms under which the Cherokee Nation were to receive a sum not exceeding five millions dollars for surrendering their lands and possessions east of the Mississippi river to the U.S. Government and agreeing to move to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River, which later became part of Oklahoma.

The Red Clay State Historic Park, located 17 miles southwest of the Church of God Headquarter in Cleveland, Tennessee, marks the last location of the Cherokee councils where Chief John Ross and nearly 15,000 Cherokees rejected the proposed Treaty of 1835. Despite the questionable legitimacy of this Treaty, in March 1838, it was amended and ratified by the U.S. Senate and became the legal basis for the forcible removal of the Cherokee Nation known as the Trail of Tears. The name came from the Cherokees who called the removal “Nunna-da-ul-tsun-yi,” which means “the place where they cried.” The last pieces of land controlled by the Cherokee Nation at that time were North Georgia, Northern Alabama and parts of Tennessee and North Carolina. The forced journey was through three major land routes. Each route could have taken some 1,000 miles and over four months to walk. The removal of the Cherokees and other tribes from their homelands in the Southeast began May 16, 1838.

The Georgia Road or present day Federal Road was a route of the Trail of Tears that the Cherokee people walked during their forced removal from their homelands. The route was built from 1803 to 1805 through the newly formed Cherokee Nation on a land concession secured with the 1805 Treaty of Tellico with the agreement that the U.S. Government would pay the Cherokee Nation $1,600.00. The Treaty was signed on October 25, 1805 at The Tellico Blockhouse (1794 – 1807) – an early American outpost located along the Little Tennessee River in Vonore, Monroe County, Tennessee that functioned as the location of official liaisons between the United States government and the Cherokee. The route was originally purposed to be a mail route because of the great need to link the expanding settlements during the westward expansion of the U.S. colonies. It was in 1819 after improvements to the road that it was called “the Federal Road”.

The Tellico Blockhouse was the starting point for the Old Federal Road, which connected Knoxville to Cherokee settlements in Georgia. The route ran from Niles Ferry on the Little Tennessee River near the present day U.S. Highway 411 Bridge, southward into Georgia. Starting from the Niles Ferry Crossing of the Little Tennessee River, near the U.S. Highway 411 bridge, the road went straight to a point about two miles east of the present town of Madisonville, Tennessee. This location is 20 some miles north of the Tellico Plains area that marks the site of the beginning of the Church Cleveland, Tennessee. The road continued southward via the Federal Trail connecting to the North Old Tellico Highway past the present site of Coltharp School, intersected Tennessee Highway 68 for a short distance and passed the site of the Nonaberg Church. East of Englewood, Tennessee it continued on the east side of McMinn Central High School and crossed Highway 411 near the railroad overpass. Along the west side of Etowah, the road continued near Cog Hill and the Hiwassee River near the mouth of Conasauga Creek where there was a ferry near the site of the John Hildebrand Mill. From the ferry on the Hiwassee River the road ran through the site of the present Benton, Tennessee courthouse.  It continued on Welcome Valley Road and then crossed the Ocoee River at the Hildebrand Landing. From this point the road ran south and crossed U.S. Highway 64 where there is now the River Hills Church of God formerly the Ocoee Church of God. Continuing south near Old Fort, the route crossed U.S. Highway 411 and came to the Conasauga River at McNair Landing. Near the south end of the village of Tennga, Georgia is an historic marker alongside of Highway 411m which states the Old Federal Road was close to its path for the next twenty-five miles southward. It would have been at this point in Tennga that the Trail of Tears would have taken a turn onto GA-2 passing the Praters Mill near Dalton Georgia to connect in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It continued on Welcome Valley Road and then crossed the Ocoee River at the Hildebrand Landing. From this point the road ran south and crossed U.S. Highway 64 where there is now the River Hills Church of God formerly the Ocoee Church of God. Continuing south near Old Fort, the route crossed U.S. Highway 411 and came to the Conasauga River at McNair Landing. Near the south end of the village of Tennga, Georgia is an historic marker alongside of Highway 411m which states the Old Federal Road was close to its path for the next twenty-five miles southward. It would have been at this point in Tennga that the Trail of Tears would have taken a turn onto GA-2 passing the Praters Mill near Dalton Georgia to connect in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Out of the 15,000 Cherokee who endured the forced migration west after the Treaty of 1835, it is estimated that several thousand died along the way or in internment holding camps. This Old Federal route is where some of Cherokee holding camps would have been located. The Fort Marr or Fort Marrow military post constructed around 1814 under the 1803 Treaty, is the last visible remains of these camps. The original fort was built on the Old Federal Road near the Tennessee/Georgia state line near the Conasauga River. It was relocated in 1965 beside U.S. Hwy. 411 in Benton and then to it’s current location in the Cherokee National Forest on the grounds of the Hiwassee/Ocoee State Park Ranger Station at Gee Creek Campground in Delano, Tennessee. This location provides access to popular Church of God water baptismal sites. In June 4, 1838 Captain Marrow reported having 256 Cherokees at his fort ready for emigration.

The Native Americans were forcefully removed from their homes, plantations and farms all because of greed. Thousands of people lost their lives including the wife of Chief John Ross. Parts of the Old Federal Road have been washed away with floods of tears, but there are parts that still remain. The Church of God, having its roots in the same territory of the Cherokee, Chickamauga, Muskogee Creek, Choctaw and Chickasaw people, plays a vital role in the process of reconciliation among the descendants of the Trail of Tears. And the historical buildings and markers along the Trail or Tears must be preserved. The churches along the route even though they were not actual structures during the time period are a historical beacon of hope which still crying out for those lost on this tragic journey.

MLK: I Have a Dream

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead.

We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”¹

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest — quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of “interposition” and “nullification” — one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

HOW Americans experience FAITH in 2020?

4 Ways to Improve Your Church in 2020

Barna Group: The State of the Church in 2020

You are reading a free research sample of State of the Church & Family Report

The Christian church has been a cornerstone of American life for centuries, but much has changed in the last 30 years. Americans are attending church less, and more people are experiencing and practicing their faith outside of its four walls. Millennials in particular are coming of age at a time of great skepticism and cynicism toward institutions—particularly the church. Add to this the broader secularizing trend in American culture, and a growing antagonism toward faith claims, and these are uncertain times for the U.S. church. Based on a large pool of data collected over the course of this year, Barna conducted an analysis on the state of the church, looking closely at affiliation, attendance and practice to determine the overall health of Christ’s Body in America.

Most Americans Identify as Christian

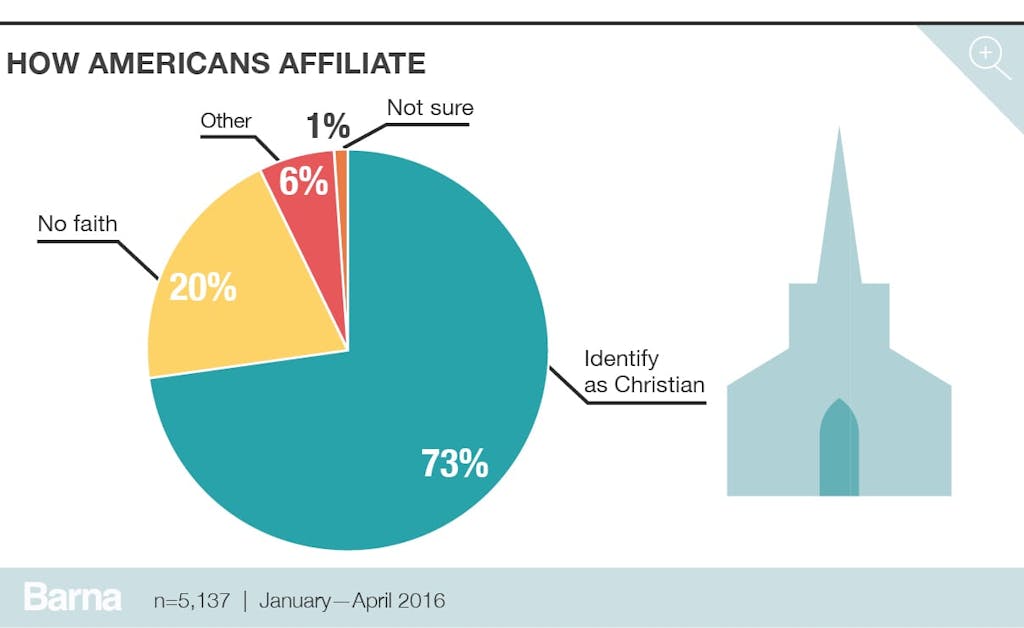

Debates continue to rage over whether the United States is a “Christian” nation. Some believe the Constitution gives special treatment or preference to Christianity, but others make their claims based on sheer numbers—and they have a point: Most people in this country identify as Christian. Almost three-quarters of Americans (73%) say they are a Christian, while only one-fifth (20%) claim no faith at all (that includes atheists and agnostics). A fraction (6%) identify with faiths like Islam, Buddhism, Judaism or Hinduism, and 1 percent are unsure. Not only do most Americans identify as Christian, but a similar percentage (73%) also agree that religious faith is very important in their life (52% strongly agree + 21% somewhat agree).

Attending Church Is a Good Indicator of Faith Practice

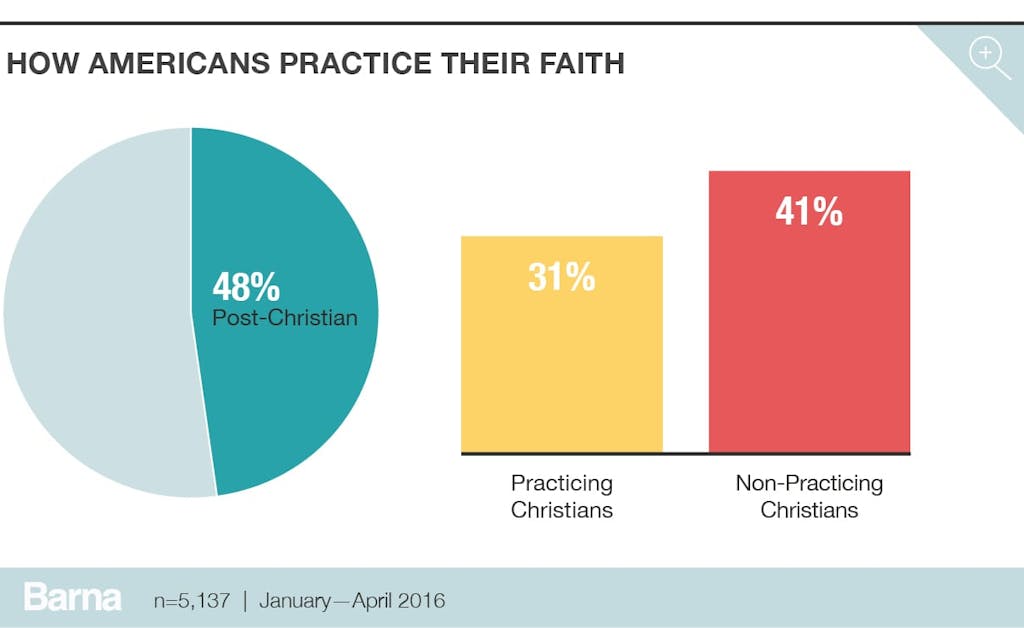

Even though a majority of Americans identify as Christian and say religious faith is very important in their life, these huge proportions belie the much smaller number of Americans who regularly practicetheir faith. When a variable like church attendance is added to the mix, a majority becomes the minority. When a self-identified Christian attends a religious service at least once a month and says their faith is very important in their life, Barna considers that person a “practicing Christian.” After applying this triangulation of affiliation, self-identification and practice, the numbers drop to around one in three U.S. adults (31%) who fall under this classification. Barna researchers argue this represents a more accurate picture of Christian faith in America, one that reflects the reality of a secularizing nation.

Another way Barna measures religious decline is through the “post-Christian” metric. If an individual meets 60 percent or more of a set of factors, which includes things like disbelief in God or identifying as atheist or agnostic, and they do not participate in practices such as Bible reading, prayer and church attendance (full description below), they are considered post-Christian. Based on this metric, almost half of all American adults (48%) are post-Christian.

Most Americans Attend Small to Medium Churches

As far as Barna is concerned, regular church attendance is central to understanding faith practice among American adults. Whether their church is large or small, charismatic or traditional, significant numbers of Americans sit in the pews each Sunday to worship together. Despite the enormous cultural impact of megachurches and megachurch pastors like Joel Osteen and his 40,000+ Lakewood Church, the largest group of American churchgoers attends services in a more intimate context. Almost half (46%) attend a church of 100 or fewer members. More than one-third (37%) attend a midsize church of over 100, but not larger than 499. One in 11 (9%) attends a church with between 500 and 999 attenders, and slightly fewer (8%) attend a very large church of 1,000 or more attendees.

There Are More Churched Than Unchurched Americans

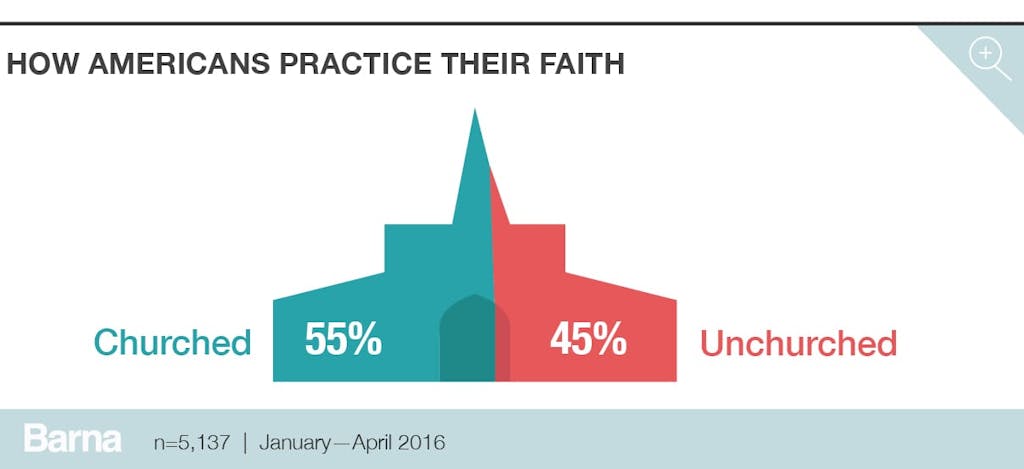

Digging deeper into church attendance, Barna uses another metric to distinguish between two main groups: those who are “churched” versus those who are “unchurched.” Churched adults are active churchgoers who have attended a church service—with varying frequency—within the past six months (not including a special event such as a wedding or a funeral). Unchurched adults, on the other hand, have not attended a service in the past six months. (They may be dechurched, meaning they once attended regularly, or purely unchurched, meaning they have never been involved in a Christian faith community.) Under these definitions, a slight majority of adults (55%) are churched—though the country is almost evenly split, with 45 percent qualifying as unchurched adults.

Christians Are More Generous Than Their Secular Peers

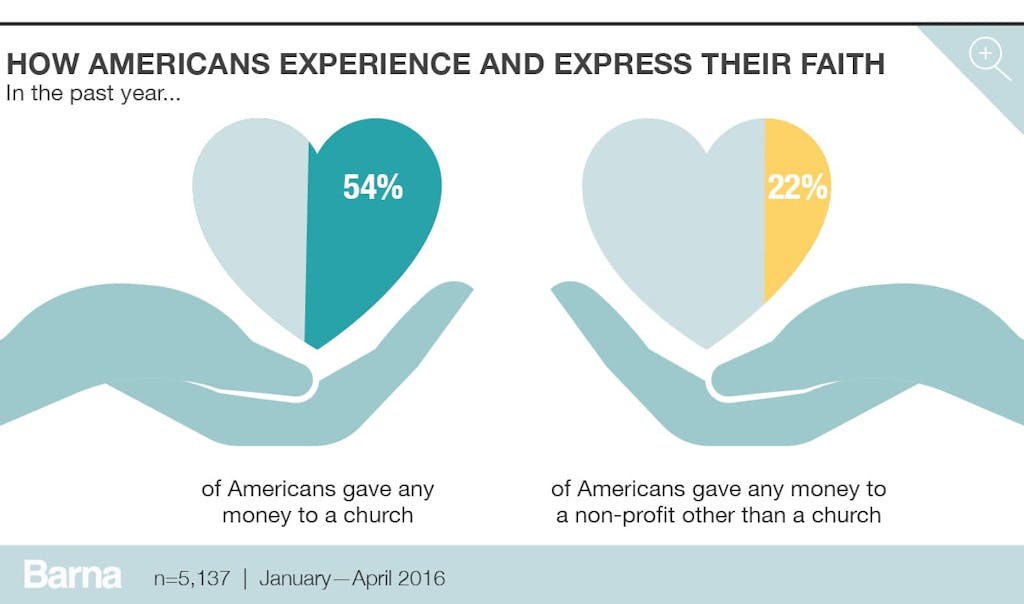

In Matthew 6, Jesus lays out three essential components of discipleship: prayer, fasting and almsgiving. The latter of the three, which we might also call justice and personal charity, is one of the pillars of a healthy spiritual life. Though residents in some cities are more generous than others, Americans give to churches more than any nonprofit organization. More than half of Americans (54%) have given money to a church in the past year—half that number have given to a nonprofit other than a church (22%). The remaining one-quarter (24%) have given to neither. Unsurprisingly almost all practicing Christians (94%) have given to a church, compared to one-quarter (23%) of atheists or agnostics. In fact, practicing Christians tend to be more generous overall than their secular counterparts: 96 percent of practicing Christians gave to a church or a nonprofit, compared to 60 percent among atheists and agnostics.

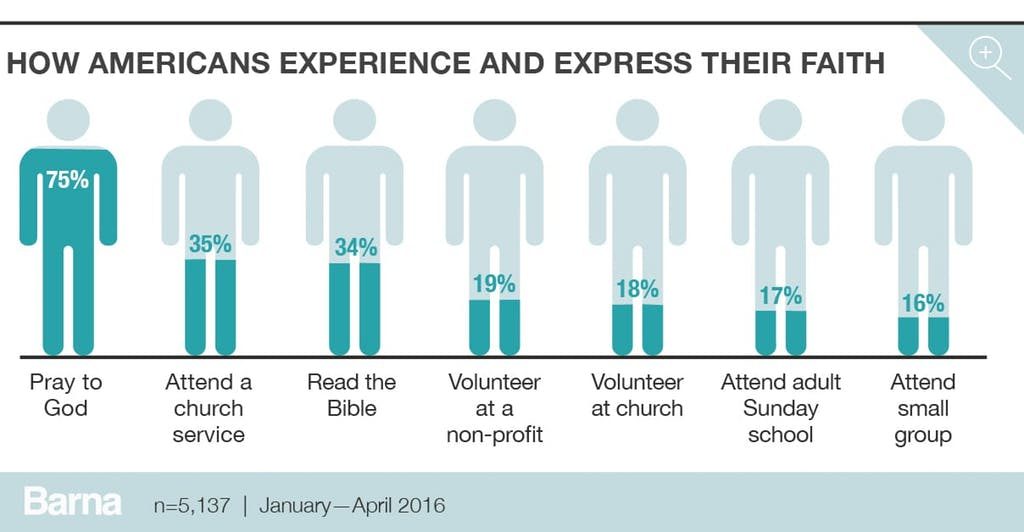

Americans Express Their Faith in a Variety of Ways

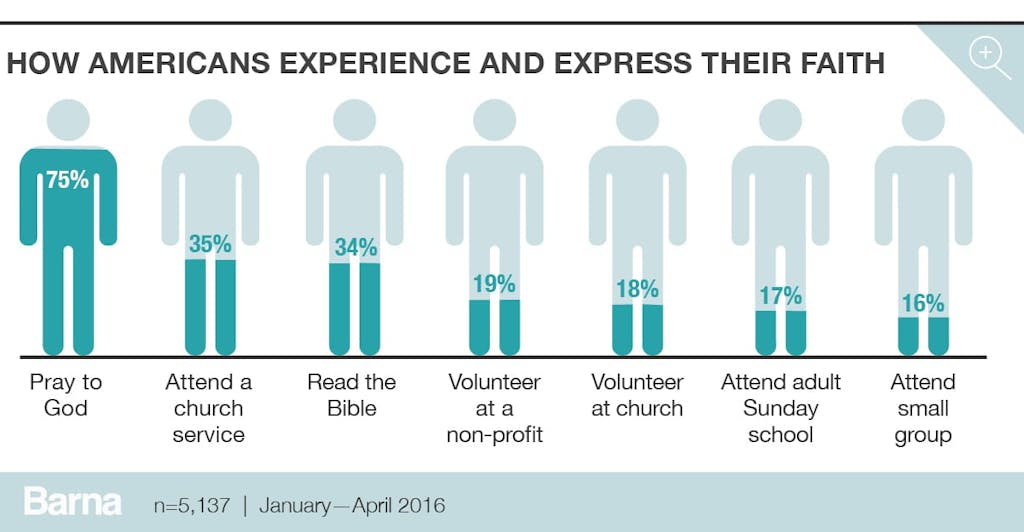

While regular church attendance is a reliable indicator of faithful Christian practice, many Americans choose to experience and express their faith in a variety of other ways, the most common of which is prayer. For instance, three-quarters of Americans (75%) claim to have prayed to God in the last week. This maps fairly well onto the 73 percent who self-identify as Christian. Following prayer, the next most common activity related to faith practice is attending a church service, with more than one-third of adults (35%) having sat in a pew in the last seven days, not including a special event such as a wedding or funeral. About the same proportion (34%) claim to have read the Bible on their own, not including when they were at a church or synagogue. About one in six American adults have either volunteered at a nonprofit (19%) or at church (18%) in the last week. Slightly fewer attended Sunday school (17%) or a small group (16%).

Evangelicals Are a Small but Influential Group

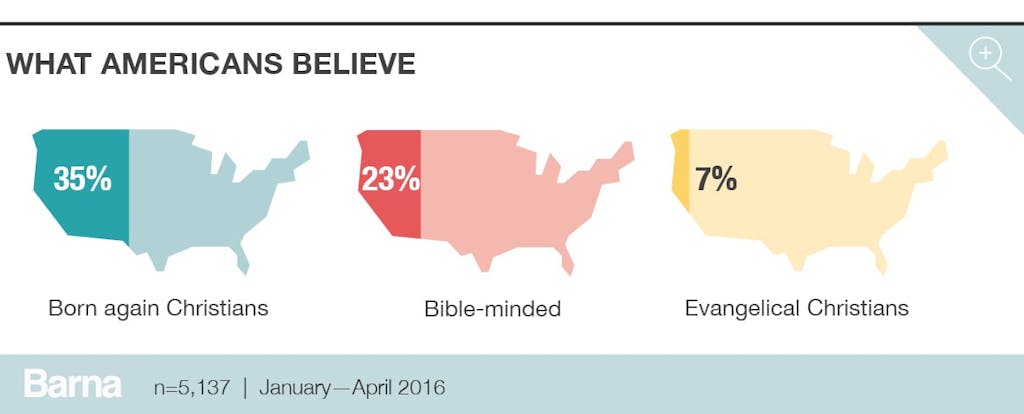

Classifications and metrics are vital to understanding the religious makeup of the United States. Barna uses several of these to identify key faith groups in America, including “born again Christians,” “evangelical Christians” and those who are “Bible-minded.” The largest of these groups are born again Christians, which make up roughly one-third of the population (35%). These individuals have made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in their life today and believe that, when they die, they will go to heaven because they have confessed their sins and accepted Jesus Christ as their savior. The next largest group are those considered Bible-minded, who make up about one-quarter of the population (23%). They believe the Bible is accurate in all the principles it teaches and have read the Scriptures within the past week. Finally, the small (7%) but influential group of evangelicals are those who meet the born again criteria plus seven other conditions (detailed below), which are made up of a set of doctrinal views that touch on topics like evangelism, Satan, biblical inerrancy and salvation.

Americans Hold Both Orthodox and Heterodox Views

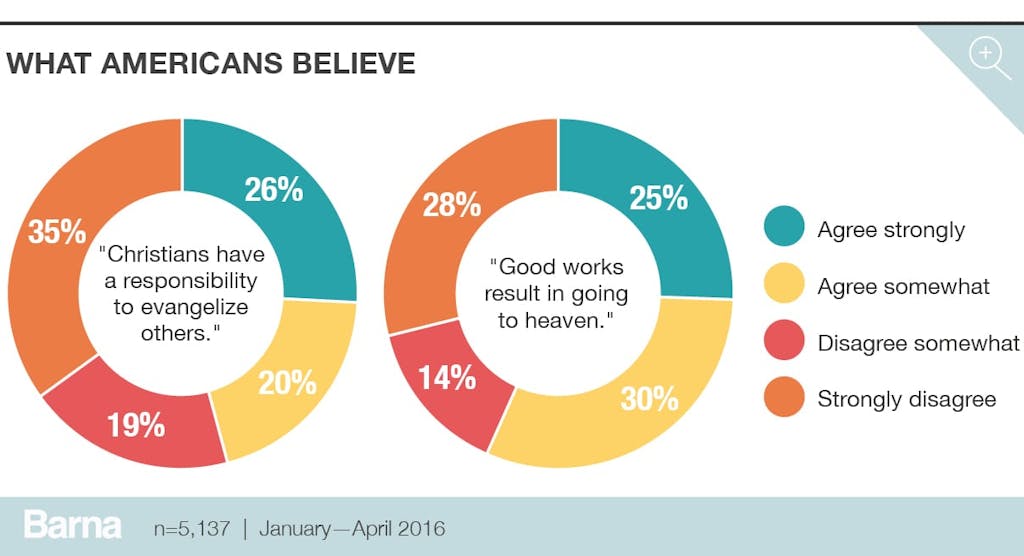

Religion and politics: two topics best excluded from polite conversation. This old adage appears to have the support of most Americans. When asked whether they, personally, have a responsibility to tell other people their religious beliefs, most people (54%) disagree (46% believe otherwise, very close to an even split). Getting at orthodoxy (or, rather, heterodoxy) among the American population, most (55%) agree that if a person is generally good, or does good enough things for others during their life, they will earn a place in heaven.

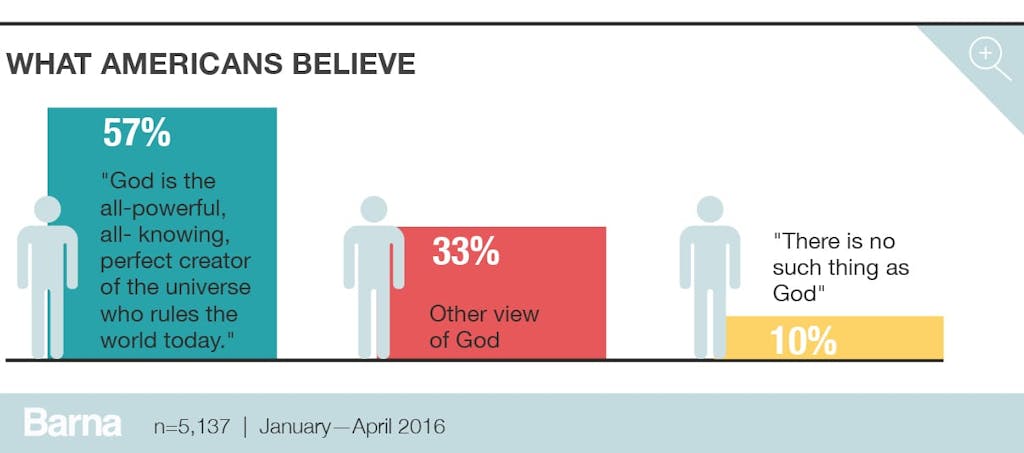

Yet in spite of the popularity of the belief that good works is sufficient for eternal life, from a long list of options for ways to describe God, the majority (57%) choose the most orthodox view: that God is the all-powerful, all-knowing, perfect creator of the universe who rules the world today. Other views of God make up one-third (33%) of the responses, and one in 10 (10%) says there is no such thing as God.

Comment on this research and follow our work:

Twitter: @davidkinnaman | @roxyleestone | @barnagroup

Facebook: Barna Group

About the Research

The study on which these findings are based was conducted via online and telephone surveys conducted in January 2016 and 2016. A total of 5,137 interviews were conducted among a random sample of U.S. adults, ages 18 years of age or older. The sample error is plus or minus one percentage point at 95-percent confidence level.

Born again: Have made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in their life today and believe that, when they die, they will go to heaven because they have confessed their sins and accepted Jesus Christ as their savior.

Evangelical Christian: Meet the born again criteria plus seven other conditions. These conditions include saying their faith is very important in their life today; believing they have a personal responsibility to share their religious beliefs about Christ with non-Christians; believing that Satan exists; believing that Jesus Christ lived a sinless life on earth; asserting that the Bible is accurate in all that it teaches; believing that eternal salvation is possible only through grace, not works; and describing God as the all-knowing, all-powerful, perfect deity who created the universe and still rules it today. Being classified as an evangelical is not dependent upon church attendance or the denominational affiliation of the church attended. Respondents were not asked to describe themselves as “evangelical.”

Bible-minded: believe the Bible is accurate in all the principles it teaches and have read the Scriptures within the past week.

Churched: attended church in the past month

Unchurched: have not attended church in the past 6 months

Practicing Christian: Those who attend a religious service at least once a month, who say their faith is very important in their lives and self-identify as a Christian

Non-practicing Christian: Those who self-identify as a Christian but do not qualify as a practicing Christian

Post-Christian: To qualify as “post-Christian,” individuals had to meet 60% or more of the following factors (nine or more). “Highly post-Christian” individuals meet 80% or more of the factors (12 or more of these 15 criteria):

- Do not believe in God

- Identify as atheist or agnostic

- Disagree that faith is important in their lives

- Have not prayed to God (in the last year)

- Have never made a commitment to Jesus

- Disagree the Bible is accurate

- Have not donated money to a church (in the last year)

- Have not attended a Christian church (in the last year)

- Agree that Jesus committed sins

- Do not feel a responsibility to “share their faith”

- Have not read the Bible (in the last week)

- Have not volunteered at church (in the last week)

- Have not attended Sunday school (in the last week)

- Have not attended religious small group (in the last week)

- Do not participate in a house church ( in the last year)

About Barna Group

The Barna Group is a private, non-partisan, for-profit organization under the umbrella of the Issachar Companies. Located in Ventura, California, Barna Group has been conducting and analyzing primary research to understand cultural trends related to values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors since 1984.

2020

In 2020, we will be celebrating 30 years in ministry. Twenty of them alone were spent in America where we have held some 3,000 services across 25+ different states. In these three decades, I have seen genuine revival with the Glory of God moving in only twice.

The first time was in 1990, right after the fall of the Berlin Wall in Bulgaria, when our youth group of a dozen students grew up to 300 during the spring semester alone. One of those nights, 26 young people literally walked through the door of the small hall we were renting, gave their lives to the Lord and were baptized with the Holy Spirit – all of them on the spot in that one service. I can still remember them all speaking in tongues and none of us knowing what just hit us. As the visible glory of God descended upon us, we were not able to shut down the service till well after midnight. We got written up for breaking curfew, but our names were written in Heaven.

The second time was at the turn of the century when in the summer of 1999 the Lord opened doors to preach over 20 revivals. I started seminary in the fall and travelled back to South Carolina literally every weekend that first semester just to finish all scheduled preaching appointments. Some of the readers of this letter well remember that one or more of those meetings were in your church. And I have been praying for the same move of God since then.

Though we have had similar trends in our ministry in 2014 and then at the start of 2017, it was only this year again that I am seeing the signs of a great revival taking place just like in 1989 and 1999. More and more ministers we contact share the same feel for another great revival and after much prayer, fasting and anticipation I have become convinced that God is on the move in 2019.

For these reasons, we are approaching this season of Revival Harvest Campaign in 2019-2020 with great anticipation. We urge you to pray along with us and seek the will of the Lord – what is it that He wants us to do in this season of upcoming Revival? A move of God of such magnitude and rarity should not be taken lightly!